1.General information

Behcet's syndrome is a rare and not yet sufficiently studied disease, which is classified as a group of systemic vasculitis (vascular inflammation). Small and medium-sized arteries are predominantly affected, which, in turn, causes the development of a specific clinical picture (see below).

A number of etiopathogenetic, classification, diagnostic and other issues regarding Behçet's syndrome remain controversial, despite the gradual accumulation of statistical data and research results. Thus, assessments of the influence of the gender factor are contradictory (some sources report a predominance of people of one gender or another among the sick, other authors deny such trends), while a certain regional dependence cannot be explained (indigenous residents of the Mediterranean, Near and Far East get sick hundreds of times more often than residents of, say, North America), opinions differ regarding trigger and etiopathogenetic mechanisms, criteria for differential diagnosis, approaches to treatment, etc.

A must read! Help with treatment and hospitalization!

How to treat Behçet's disease?

When Behcet's disease is diagnosed, complex, long-term and systemic treatment is carried out. It is prescribed taking into account the location of the lesion and the individual characteristics of the body strictly in the hospital. Since the etiology of the disease has not been established, only symptomatic treatment is provided, aimed at relieving clinical signs and preventing complications.

Drug therapy consists of prescribing medications to patients from various pharmacological groups:

- Anti-inflammatory - “Ibuprofen”, “Diclofenac”, “Indomethacin”,

- Antihistamines - “Suprastin”, “Tavegil”, “Cetrin”,

- Antiviral - “Acyclovir”, “Isoprinosine”,

- Antibacterial - Azithromycin, Cefazolin, Coprofloxacin,

- Vasodilators - “Pentoxifylline”, “Nicotinic acid”,

- Vitamins - “Aevit”, “Oligovit”,

- Anticoagulants - “Aspirin”, “Trental”, “Curantil”,

- Antigout - Colchicine, Allopurinol,

- Hormonal - "Prednisolone", "Dexamethasone",

- Cytostatics - Cyclophosphamide, Methotrexate.

Local treatment includes: mouth rinsing and treating ulcers with antiseptics, the use of ointments with hepatrombin, indomethacin, glucocorticoids, subconjunctival administration of Dexamethasone.

In severe cases, they resort to extracorporeal therapy: plasmapheresis, hemosorption, ultraviolet irradiation, laser therapy, ultrasound, inductothermy. The use of surgical treatment methods will help eliminate the negative consequences of the pathology.

2. Reasons

The immediate causes and patterns of development of Behcet's syndrome are one of the most pressing issues. Since the first clinical descriptions and studies (30-40s of the twentieth century), many assumptions and hypotheses have been put forward, the most well-reasoned of which were hereditary, infectious, and autoimmune. However, for example, the viral or bacterial (streptococcal) hypothesis about the nature of this disease is today considered refuted and untenable, although some authors continue to insist on it. Much uncertainty remains regarding the mechanisms of inheritance, triggering factors of immune and biochemical disorders, etc.

Reliable provoking factors include long-term (many years and daily) alcohol consumption, the presence of chronic infectious and inflammatory foci, etc.

The genetic factor is clearly visible in some cases and absent in others.

Visit our Rheumatology page

3. Symptoms and diagnosis

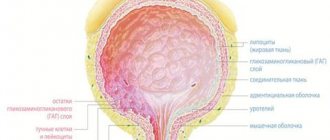

The clinical picture of Behcet's syndrome is nonspecific, very polymorphic and very variable both in severity and types of course. Previously, a typical triad was considered to be a combination of ulcerative stomatitis, ulcerative inflammation of the genitals and inflammation of the ocular structures (uveitis, iridocyclitis, conjunctivitis). However, today a wide range of symptoms have been identified that are equally or even more characteristic of Behcet's syndrome, namely:

- joint inflammation (arthritis);

- skin lesions characteristic of vasculitis in general (papules, pustules, erythema, etc.);

- thrombophlebitis;

- damage to the central nervous system;

- pathology of the gastrointestinal tract;

- reproductive system disorders;

- in rare cases - pulmonary, cardiac, renal pathology, oncological processes.

All of these symptoms and complications are non-pathognomonic (i.e., they may indicate any of a variety of other diseases); in addition, they may not appear all at once, but sequentially, one after another, in certain combinations - sometimes over many years. And yet, based on the recognizable combination of the following manifestations, the nature of the clinical picture and the transformation of the symptom complex, Behcet's syndrome can (and therefore should) be diagnosed at least at the level of the dominant assumption.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that with Behcet's syndrome there are not only clinical, but also laboratory indicators that (or certain combinations of which) would become a decisive and unambiguous confirmation of the diagnosis.

About our clinic Chistye Prudy metro station Medintercom page!

Behçet's disease (BD) is a systemic vasculitis of unknown etiology, manifested by recurrent aphthous stomatitis, genital ulceration, uveitis and skin lesions [1]. These symptoms form the basis of the International Criteria for the Disease [2]. “Minor” manifestations of the disease, which are less common, but often determine the prognosis of BD, include neurological and vascular (peripheral venous and arterial thrombosis, arterial aneurysms) disorders. It is neurological (12–20%) and vascular (41–43.9%) disorders, including damage to intracerebral vessels, that are the main cause of deaths in BD [3].

The frequency of neurological disorders in BD, according to the literature [4, 5], ranges from 2.2 to 59%. As a rule, they are detected 3–6 years after the onset of BD [6]. However, there are cases when BD debuts with symptoms such as coma, meningitis, acute confusion, aphasia, tetraparesis, acute sensorineural hearing loss, which significantly complicates the early diagnosis of the disease [7–10]. On the other hand, in BD there are known cases of asymptomatic CNS damage, diagnosed using psychometric and instrumental studies. H. Zayed et al. [11] when examining 25 patients with BD who did not have clinically significant neurological and mental disorders, found changes in the nervous system with single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) in 64% of patients, and with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) - only in 25% . The results of psychometric testing showed that 96% of patients had signs of depressive disorder and 92% of anxiety disorder. In the work of Portuguese researchers [12], subclinical neurological and mental disorders were found in 27-75% of patients with B.B. The significance of asymptomatic CNS damage in BD is not clear, however, in the work of H. Yesilot et al. [13] showed that approximately 20% of patients with BD without neurological symptoms, but who had changes in MRI and some neurophysiological tests, developed neurological manifestations after an average of 13 years.

For more than 70 years since the first description of BD by the Turkish dermatologist H. Behҫet, researchers in various countries have tried to systematize its clinical manifestations. The result was several variants of classification diagnostic criteria, in which neurological and mental manifestations were classified as “minor” criteria. Over the years, rheumatologists and neurologists from many countries have described and tried to classify various neurological disorders in BD [14, 15]. In 2012, based on the results of a 20-year multicenter study in Japan, preliminary diagnostic criteria for the classification of neurological and psychiatric manifestations of BD were proposed [16]. The basis of the latter was the identification of acute and chronic variants of progressive damage to the central nervous system (Table 1). In our opinion, the advantage of this classification was that it took into account not only neurological, but also mental manifestations (cognitive and behavioral disorders). However, this classification has not been widely used. In 2014, international clinical guidelines were developed based on the opinions of 52 experts from 22 countries. They are distinguished by an integrated approach to the assessment of neurological manifestations of BD and contain their refined classification taking into account the International Criteria for the Diagnostics of BD (ISGBD, 1990) (Tables 2 and 3) and, in fact, recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of neurological disorders in BD, consistent with recommendations of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR, 2008) (Table 4, 5, 6) [17, 18]. Mental disorders that occur in BD and are no less important, unfortunately, are not reflected in these recommendations.

Table 1. Preliminary diagnostic criteria for the classification of neurological disorders in BD (Japan, 2012) [16]

Table 2. Criteria for neurological disorders in BD (international consensus recommendations (ICR)), 2014. Note. ISGBD - International Study Group Behҫet Disease Criteria - International criteria for the diagnosis of BD 1990.

Table 3. Classification of neurological disorders in BD

Table 4. Recommendations for diagnosing neurological disorders in BD

Table 5. Recommendations regarding the role of investigations in the diagnosis of neurological disorders in BD

Table 6. Recommendations for the management of patients with neurological manifestations of BD

Clinical aspects of BD

Criteria and classification of neurological manifestations of BD

In order to improve the diagnosis of neurological disorders in BD, an international group of experts proposed criteria for a definite and probable neurological disorder (see Table 2).

There are two main types of CNS lesions in BD - parenchymal and non-parenchymal (see Tables 3 and 4). Neurological manifestations in BD are nonspecific and include the following signs [19]: headache; meningoencephalitis; recurrent aseptic meningitis or isolated encephalitis; benign intracranial hypertension; ataxia and symptoms of cerebellar damage; neuropathy of the oculomotor and other cranial nerves; speech disorders (dysarthria, aphasia); transient ischemic attack and acute cerebrovascular accident; bulbar and pseudobulbar palsy; spinal disorders; multiple sclerosis-like disorder; pyramidal and extrapyramidal disorders; neuritis, polyneuritis; dementia; convulsive syndrome; confusion; loss of vision, diplopia, nystagmus.

Specific to BD is parenchymal damage to the brainstem, characterized by multiple foci of necrosis in the white and gray matter of the brain, most often in the brainstem, basal ganglia and internal capsule, resulting in brain atrophy and clinical symptoms such as ophthalmoparesis, neuropathy of the cranial nerves, cerebellar dysfunction and pyramidal insufficiency. Multifocal/diffuse parenchymal damage to the brainstem, hemispheres of the brain and spinal cord often occurs, manifested by multiple neurological symptoms, in particular headache, hemiparesis, convulsions, dysphasia, and dysfunction of the sphincters. According to some authors [4], parenchymal damage to the central nervous system is observed in approximately 80% of BD patients with neurological disorders.

Nonparenchymal CNS involvement includes cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST), intracranial hypertension syndrome (pseudotumor syndrome), cerebral arterial aneurysms, extracranial arterial aneurysms/dissections, and acute meningeal syndrome.

Isolated spinal cord lesions are rare in BD. Neurological symptoms in BD are not always associated with the disease itself, but may be caused by concomitants, such as chronic migraine, acute cerebrovascular accident (ACVA), or be associated with undesirable effects of BD therapy, secondary infection and neoplasms [17].

The most common (42.4–63%) neurological symptom in BD is headache [12, 16]. In most cases, it is not associated with BD and may be a manifestation of chronic migraine or classified as tension headache. In only 10% of cases, headache in BD is associated with the underlying disease, most often with SIB, and, as a rule, is combined with other neurological symptoms [17].

If neurological disorders are present already at the onset of the disease, then differential diagnosis of BD with multiple sclerosis (MS) and other systemic inflammatory diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjogren's disease, sarcoidosis and primary CNS lymphoma) is carried out. Sensory disturbances, optic neuritis, internuclear ophthalmoplegia, ataxia and cerebellar dysarthria are more common in MS, while headache, motor and pseudobulbar disorders and cognitive-behavioural impairment are more common in B.B. In addition, oligoclonal secretion is found in the CSF of most patients with MS, which is not typical for B.B. Neutrophils predominate in the CSF of patients with BD, while the CSF of patients with MS is characterized by a predominance of lymphocytes. All 19 neuropsychiatric manifestations characteristic of SLE can also occur in BD, which brings these diseases closer together. At the same time, so-called “diffuse” mental syndromes are more typical for SLE - headache, mental disorders (anxiety-depressive, psychotic), and for BD - “focal” ones (neuropathy of the cranial nerves, symptoms of damage to the brain stem, basal ganglia) [ 5]. In the case of a combination of uveitis with diencephalic syndrome, it is necessary to differentiate BD from primary CNS lymphoma. Acute parenchymal damage to the central nervous system in BD can simulate stroke (see Table 4).

Mental disorders in BD

Mental disorders are typical for 26.5–88.3% of patients with BD, but in most publications they receive much less attention than neurological disorders. It has been established that the quality of life and ability to work in the presence of mental disorders in patients with BD is significantly lower than without them [20-22]. Their influence on the clinical picture, prognosis and outcomes of BD has not been sufficiently studied to date.

In recent years, it has been established that depression is a significant independent risk factor for increased mortality in rheumatic diseases, in particular rheumatoid arthritis (2.5-3.5 times) [23]. In case of depression, significantly lower (3 times) rates of adherence to treatment in patients with chronic somatic diseases were noted [24], which can be explained by the influence of several factors: depressive experiences with a lack of hope for recovery, cognitive impairment (CI) and suicidal behavior. One of the common variants of this behavior is the refusal of patients to treat a somatic disease.

As with other rheumatic diseases, a close connection with depression can be noted in BD, due to the influence of common pathogenetic, primarily stress, factors [25]. Mental disorders can precede BD, begin simultaneously, or already against its background. No less significant in their development is the role of organic factors of the central nervous system, provoking the formation of psychoorganic syndrome and CI.

There is an opinion that, in terms of frequency and spectrum, mental disorders in BD are most similar to those in SLE [5, 20, 21]. Most often (44.4–88.3%) in patients with BD, depressive, anxiety disorders and CI are observed, mainly in a mild form [5, 21]. Anxiety-depressive spectrum disorders (ADDS) are detected in 20.6–86.7% of patients with BD [20, 21]. Among them, chronic variants of depression predominate: dysthymia (33.3%) and recurrent depressive disorder (28.3%) [21]. Anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, adjustment disorder with anxiety-depressive syndrome) occur in 13–23.5% of patients with BD [20, 21]. It has been noted that the severity of depression and anxiety in RTDS in patients with BD is higher in the presence of arthritis [22]. Acute psychoses occur extremely rarely in patients (2.9%), in particular manic psychoses (5.9%), and their occurrence cannot be ruled out by the influence of therapy with high doses of glucocorticoids [20, 26]. There is evidence of the possible development of obsessive-compulsive disorder and panic attacks (panic disorder) while taking azathioprine [27]. Bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia are practically not found in BD—only isolated cases have been described [28, 29]. Such a large difference in the frequency of mental disorders in BD, according to different authors, is probably due to the cultural characteristics of the patient samples and the difference in the psychometric assessment tools used by the authors. In most studies, any mental disorders, including CI, are associated with BD, although there is another point of view that suggests the influence of factors not related to the underlying disease on their occurrence [30–32]. It has been shown that mild CI in BD is more associated with a low educational level of patients, alcohol and substance abuse, and participation in hazardous sports (wrestling, boxing). Moderate K.N. are accompanied by higher BD activity and are often combined with parenchymal damage to the central nervous system and depression [12, 21, 31]. As a rule, a reduction in mild and moderate CI is observed against the background of adequate therapy for BD and psychopharmacotherapy for depression.

The main factors influencing the development of mental disorders in BD currently include stress [12]. It has been proven that in 80% of patients with BD, the development of RTDS, as well as BD itself, was preceded by acute or chronic stress factors; 58.3% of patients experienced traumatic events in childhood and adolescence [21]. Despite the presence of this kind of data, a number of authors believe [21, 33] that mental disorders develop against the background of BD; with an increase in the duration of BD over 3 years, the risk of developing the latter increases 12 times.

Sleep disturbances occur in approximately 30% of patients with B.B. They are more often associated with RTDS [34]. 32.5% of patients with BD suffer from obstructive sleep apnea syndrome [34]. One-third of patients are characterized by restless legs syndrome, a sensorimotor disorder characterized by unpleasant sensations in the lower extremities that appear at rest, more often in the evening and at night, forcing the patient to make movements that relieve them and often lead to sleep disturbances. The pathogenetic mechanisms of this pathology are not fully understood. In 2011, a group of authors from Turkey [35] showed that the syndrome in question occurs in patients with BD more often than in the population (29.4 and 4.8%, respectively). In this study, it was observed that its severity was positively correlated with the duration of BD.

Sexual disorders in patients with BD are regarded by some researchers as a result of the depressogenic effect of chronic inflammation. Sexual dysfunction was found in 47.9% of examined women with BD (in the control group - in 17.5%). Compared to controls, the average score on the Beck Depression Self-Assessment Inventory in patients with BD was significantly higher, and the sexual functional index correlated with this indicator. No statistical connection was found between ulcerative lesions of the genital skin and this index in patients [36]. A similar study among men also did not establish a connection between reduced erectile function and ulcerative lesions of the genital skin, mucous membranes, eye pathology, characteristics of therapy and severity of the disease, but a correlation was identified with the severity of depression [37].

Thus, despite the great interest in the study of mental disorders in BD, many unresolved questions remain, in particular, whether such disorders in BD are a manifestation of organic damage to the central nervous system as part of the underlying disease, or are they independent comorbid disorders that have common provoking factors with BD, in in particular, stress and associated dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system and impaired immune response. It also remains unclear what the nature of CI is - organic, associated with parenchymal damage to the central nervous system, or whether CI is largely caused by RTDs. Answers to these questions are extremely important for determining approaches to the treatment of mental disorders in BD. Currently, most researchers propose an integrated therapeutic approach - active anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapy for BD and psychopharmacotherapy, including antidepressants, antipsychotics and akatinol memantine for the correction of severe CIs [38]

Laboratory and instrumental studies in the diagnosis of neurological disorders in BD

Serum inflammatory markers

Despite the fact that an increase in ESR and other serum inflammatory markers is associated with BD activity, there is no clear connection between them and neurological disorders (see Table 4). There are several studies confirming that exacerbation of neurological symptoms of BD is accompanied by exacerbation of its other systemic manifestations. Only one study noted an increase in the concentrations of a number of inflammatory markers in less than ¼ of patients with neurological manifestations of BD [17].

Neuroimaging data

Neuroimaging (see Table 5), especially magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is important in the diagnosis of neurological disorders in BD. Changes detected on MRI in BD are now well described in the literature.

The acute/subacute phase of parenchymal CNS lesions on MRI are characterized by focal changes that have a hypo- or isointense signal on T1-weighted images (T1WI). Enhancement of lesions with intravenous administration of gadolinium contrast agents has been described. On T2-weighted images (T2WI) as well as FLAIR images, these lesions have a hyperintense signal. In addition, a decrease in diffusion coefficient in lesions on diffusion images has been described [17].

In the chronic phase of parenchymal lesions, focal MRI changes partially regress until complete resolution, and also do not accumulate contrast agent. At the site of the lesions, areas of atrophy may form, which is especially characteristic of the brain stem. For this phase, nonspecific focal changes in the white matter of the brain are common, which sometimes causes difficulties in making a differential diagnosis with MS [17].

A typical localization of focal changes in parenchymal lesions of the central nervous system in patients with BD is the brain stem. Lesions are usually found in the pons, midbrain, basal ganglia, and diencephalic structures. Multiple small lesions in the white matter of the brain in BD are usually localized subcortically. They are not always located in the periventricular areas, which fundamentally distinguishes them from damage caused by R.S. The latter is characterized by a predominant localization of lesions precisely periventricular and rare involvement of the basal ganglia, internal capsule and peripheral part of the pons. Note that subcortical localization of lesions is also characteristic of SLE, but unlike BD, damage to the brain stem and basal ganglia is not typical for this disease. In the case of single isolated changes in the cerebral hemispheres, differential diagnosis with a tumor, abscess and congenital cysts is necessary [17].

Single or multiple inflammatory changes of varying extent can be detected in the cervical or thoracic spinal cord. They are usually combined with changes in the brainstem, basal ganglia or other parts of the brain. Isolated lesions in the spinal cord are extremely rare [17].

To identify non-parenchymal lesions of the central nervous system in BD, namely CVS or thrombosis of intracerebral veins, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed venography (CV) is indicated. In the case of acute meningeal syndrome, MRI with intravenous contrast enhancement is recommended to confirm the involvement of the meningeal membranes (see Table 5) [17].

Many authors confirm the high informativeness of SPECT with Tc in diagnosing CNS lesions in B.B. This technique is of particular interest due to its ability to demonstrate early subclinical perfusion disturbances and local metabolic changes in the brain, which are often asymptomatic and may precede clinically pronounced neuropsychiatric manifestations of BD. A. Garcia-Burillo et al. [19] showed that according to SPECT data, 69.7% of patients with BD had disorders, among whom only 36% had clinical and MRI signs of CNS damage. The authors propose this technique not only to identify early changes in the central nervous system associated with BD, but also to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of therapy for neurological disorders in BD.

Cerebrospinal fluid

Changes in the CSF are detected in 70-80% of BD patients with parenchymal lesions of the central nervous system [4, 17, 39]. The protein concentration in the CSF is moderately increased, and oligoclonal secretion is usually absent. In 60-80% of cases of parenchymal damage to the central nervous system in BD, leukocytosis occurs in the CSF up to 4.0 × 103 leukocytes/l. Leukocytosis can be due to neutrophilia (more often), lymphocytosis, or be mixed in cellular composition. The level of glucose in the CSF with CNS damage in patients with BD is usually not changed. If this indicator decreases, it is advisable to exclude infection. Patients with SIB or intracranial hypertension without sinus thrombosis (pseudotumor syndrome) usually have normal CSF, but the pressure at which it leaks is increased (see Table 5) [17].

Interleukin-6

Serum concentrations of interleukin-6 (IL-6) generally correlate with BD activity, and its content in the CSF is usually elevated in acute parenchymal CNS lesions [40, 41]. Increased CSF IL-6 concentrations in parenchymal CNS disease are often associated with increased CSF protein and leukocyte concentrations, and these three parameters are associated with BD activity and prognosis at 3 years of follow-up. It is extremely rare that an increase in the level of IL-6 in the CSF with parenchymal damage to the CNS in patients with BD is not accompanied by an increase in protein and leukocytes in the CSF [17].

Studies by Japanese authors [17] demonstrated a decrease in the level of IL-6 in the CSF in response to various therapy with B.B. Since these studies included a small number of patients, clear conclusions cannot be drawn about the need to study this marker to monitor the treatment of neurological disorders in BD.

Pathergy test and neurological disorders

In the seventh recommendation for diagnosing neurological manifestations of BD, the authors [17] suggest using a pathergy test when neurological disorders within BD are suspected, since a positive result, especially in combination with other systemic manifestations of the disease, makes a significant contribution to the diagnosis (see Table 5) [17]. However, despite the fact that this symptom is included in the diagnostic criteria for BD, it is not pathognomonic. A false-positive pathergy test may occur in pyoderma gangrenosum.

, Sweet syndrome, inflammatory bowel diseases, familial Mediterranean fever, acute myeloid leukemia and during interferon-α therapy [42, 43]. In addition, the pathergy test has significant geographic variation. While 60–70% of patients with BD in Turkey and Japan have a positive pathergy test, it is almost never found in patients with BD in Northern Europe and North America [17, 43].

HLA-B 51 and neurological disorders

In the eighth recommendation [17], the authors point out that despite the association of BD with positivity for HLA-B5 and, more precisely, with the HLA-B51 allele, it is still unclear whether HLA-B51/B5 testing has value for diagnosis and prognosis of BD and neurological disorders within its framework (see Table 5). Most studies have not revealed a correlation between the neurological manifestations of BD or their more severe course with HLA-B51/B5 positivity [17, 44].

Neurophysiological tests

Neurophysiological tests may be useful in diagnosing peripheral nervous system lesions or optic nerve lesions in BD [17].

EEG can be used in the differential diagnosis of BD and acute viral encephalitis [45]. Visual evoked potentials are helpful in determining optic nerve damage, but concomitant uveitis, which is common in BD, may invalidate this technique [46]. Most research results demonstrate various abnormalities in neurophysiological tests in the absence of clinical symptoms of damage to the nervous system [47, 48]. These are, in particular, asymptomatic nerve conduction disorders, electromyography results, motor, sensory or brainstem evoked potentials. Thus, the diagnosis of neurological disorders in BD cannot be based only on data from neurophysiological tests (see Table 5) [17].

Nerve tissue biopsy

Pathomorphological changes occurring in the tissues of the nervous system in BD are not pathognomonic, but are well described in the literature. The main pathomorphological manifestations of acute/subacute parenchymal damage to the central nervous system are perivascular infiltration of lymphocytes, neutrophils and rarely eosinophils with or without signs of necrosis (perivasculitis). In later stages, inflammatory infiltration is less common and gliosis and axonal loss predominate [49].

Since biopsy is an invasive procedure, it is recommended to resort to it only when other diagnostic options (clinical, neuroimaging and CSF analysis) have been exhausted, in particular in cases of tumor-like manifestations (see Table 5) [17].

Additional methods in the diagnosis of mental disorders

In addition to the clinical psychopathological examination of patients, screening and psychometric scales accepted in modern psychiatry and the formulation of a diagnosis according to ICD-10 are recommended for the diagnosis of mental disorders [50]. The most commonly used screening scale is the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [51]. The psychometric scales used are the Montgomery and Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) [52] and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) [53] (Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale). HAM-A), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Beck's anxiety inventory (BAI) [54], State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T) [55], a battery of standard neuropsychological tests to determine CI [12, 20, 56].

Tactics for managing patients with neurological disorders in BD

Treatment of parenchymal lesions of the central nervous system

To date, no controlled or comparative clinical studies have been conducted on the treatment of neurological manifestations of BD [18]. Most neurologists with experience in the treatment of BD, in case of exacerbation or acute manifestation of the disease, use intravenous infusions of methylprednisolone 1 g/day for several days, followed by the administration of an anti-inflammatory dose of GC orally for 2-3 months with a slow decrease in their daily dose to a maintenance dose. similar to the treatment used for other inflammatory diseases affecting the central nervous system (SLE and sarcoidosis) [18, 57, 58]. To avoid early relapses, it is important to avoid abrupt cessation of therapy. The dosage and duration of initial intravenous and subsequent oral GC therapy vary widely between centers [59] (see Table 6) [17].

Retrospective studies show that 2/3 of patients with damage to various parts of the brain experience good recovery after a course of GC therapy, but 1/3 of patients with BD have frequent relapses and progression of neurological disorders [4, 17]. The prescription of disease-modifying drugs is indicated for neurological manifestations of BD and is aimed at controlling the inflammatory process, reducing or preventing exacerbations, and reducing the dose of oral GCs [17, 18]. In many international centers, the first-line drug aimed at relieving various serious manifestations of BD, including neurological ones, is azathioprine [17, 18]. There are also studies that confirm the successful use of mycophenolate mofetil [60], methotrexate [61], chlorambucil [62] and cyclophosphamide [63] for neurological symptoms of BD (see Table 6) [17, 18].

A number of studies confirm the effectiveness of TNF-α inhibitors for neurological manifestations of B.B. The greatest experience has been accumulated with infliximab [64, 65]. It has been shown to have a rapid positive effect not only in the acute stage of neurological disorders, but also to maintain its effectiveness during follow-up for 1 and 4 years [66, 67]. As an alternative to the ineffectiveness of infliximab, a number of authors [68, 69] recommend the use of adalimumab. Several cases of successful use of etanercept [70], tocilizumab [71] and interferon-α [72] have been described.

Eye damage in BD is an indication for the prescription of cyclosporine. It must be remembered that it may have a neurotoxic effect and therefore should not be prescribed or should be discontinued in patients with BD and suspected neurological disorders (see Table 6) [17, 18, 73, 74].

Treatment of thrombosis of the cerebral venous sinuses

Standard therapy for systemic venous thrombosis and SVT of any etiology usually includes anticoagulants [75]. However, their prescription for TVS in patients with BD is the subject of active debate. There is still no accurate data confirming the opinions of various parties. Opponents of the use of anticoagulants believe that CVS in BD occur as a result of the inflammatory process, and the resulting thrombus is tightly fixed to the vessel wall [76], which is the basis for prescribing only anti-inflammatory drugs. In addition, there is a possibility of rupture of an arterial aneurysm of one location or another when anticoagulants are prescribed to patients with BD, which can have serious consequences [77]. Proponents of anticoagulants agree to use anti-inflammatory drugs to combat the inflammatory nature of thrombosis, but prefer to prescribe them after excluding arterial aneurysms to reduce the risk of further increase in the size of the thrombus in the cerebral venous system. International recommendations take into account the opinions of both sides [17] (see Table 6). When anticoagulants are prescribed, the duration of their use is usually 3–6 months [78]. However, in cases where there is clear evidence of the presence of any prothrombotic factors in the patient, lifelong use of anticoagulants is also possible.

Prognostic factors

According to retro- and prospective studies on the neurological aspects of BD, damage to the brainstem and spinal cord, frequent exacerbations, early progression and pleocytosis in the CSF with parenchymal lesions of the central nervous system are recognized as poor prognostic factors (see Table 6). Disability and inability to self-care at the onset of the disease, exacerbation with a decrease in the dose of GC, fever, meningeal symptoms and bladder dysfunction are also considered as possible factors associated with a poor prognosis. Gender, the presence of other systemic manifestations of BD and age at the onset of the disease do not in any way affect the prognosis of neurological disorders in BD. Although there are no data from randomized controlled trials, international experts recommend the early use of modifying drugs when one or more unfavorable prognostic factors are identified in a patient with BD and neurological symptoms (see Table 6) [17].

Conclusion

Neurological and mental disorders in BD significantly affect the severity of the disease and, in the absence of timely diagnosis and adequate therapy, significantly worsen the prognosis and increase the risk of death. The recommendations for the classification, diagnosis and treatment of neurological disorders proposed by an international group of experts [17] will allow all specialists faced with this severe manifestation of BD to promptly diagnose and prescribe adequate therapy, which will help avoid progression of the lesion, improve the quality of life of patients and the prognosis. Further study of ADRs in BD will provide a better understanding of their relationship with BD for the prevention of consequences and will contribute to the inclusion of such disorders in classification criteria and recommendations for the management of patients with BD.