Amebiasis - symptoms and treatment

Amoebiasis (Amoebic Dysentery) is an acute and chronic disease that is caused by pathogenic strains of dysenteric amoeba. Penetrating into the body, they lead to ulcerative damage to the intestines, which is accompanied by moderate intoxication, stool disorders, weight loss and sometimes the appearance of abscesses in the liver, intestines, lungs and brain. The disease can last a long time, sometimes leading to death, especially in weakened patients and in the absence of medical care.

Pathogen

Taxonomy:

- domain - eukaryotes;

- branch - amoeba-like;

- type - Evosea;

- class - Archamoebae;

- family - Entamoebidae;

- genus - Entamoeba (entamoeba);

- species - dysentery amoeba (Entamoeba histolytica).

The Russian scientist F. A. Lesh was the first to describe the pathogen and prove its pathogenicity in 1875. At least 22 strains have now been isolated, of which 9 are pathogenic, and the remaining 13 are most likely not pathogenic for humans.

Changing during life, amoebas go through two stages of development:

- the vegetative, or active, stage in the form of a trophozoite ;

- a resting stage, or "dormant" stage, in the form of a cyst .

The vegetative stage divides amoebas according to function and structure into large vegetative, luminal and tissue. All of them, suddenly entering the external environment, die within 30 minutes.

Large vegetative trophozoites (forma magna) reach 20-60 microns. This form of amoebas moves due to forward thrusts. Contains the nucleus and cytoplasm - the main part of the cell. The cytoplasm is divided into a glassy transparent mass and an inner liquid layer with digestive vacuoles in which red blood cells captured by the amoeba are digested. In acute amoebiasis, large trophozoites are detected in fresh feces - “warm feces”. Capable of breaking down protein molecules. They have surface pectins, with the help of which amoebas attach to the intestinal mucosa.

The luminal vegetative trophozoites (forma minuta) are much smaller than the large form: they reach 15-20 microns. Such trophozoites are inactive. They have one core, which is not visible without coloring. Their cytoplasm contains small vacuoles, but without erytrophytes. Luminal trophozoites live in the upper part of the large intestine, feed on bacteria, reproduce, and do not cause obvious harm. They are detected in the feces of acute amoebiasis at the beginning of recovery, in chronic amoebiasis, as well as in amoeba carriers, but to identify them it is necessary to carry out deep intestinal lavages or examine the final portions of feces after taking a saline laxative. In the lower part of the large intestine, with a gradual deterioration of conditions, for example, lack of fluid, disruption of the bacterial flora, taking medications or changes in the pH of the environment, they usually transform into a cyst form, which is gradually released into the environment. If the body's defenses are weakened, luminal trophozoites can transform into a larger vegetative form and become aggressive.

Tissue vegetative trophozoites are formed from the luminal form, but are similar in appearance to the vegetative one. They reach 20-25 microns, are mobile, parasitize, penetrating the mucous membrane of the colon, and infect the intestines. They are detected only in acute amoebiasis in the affected organs; they are found extremely rarely in liquid feces - during the disintegration of intestinal ulcers.

Cysts form from the luminal form in the lower parts of the colon. They have a round shape and reach 8-15 microns. They are immobile, covered with a dense shell of chitin, and contain chromatoid bodies (RNA with protein) and glycogen. Depending on the maturity of the cysts, they contain from 1 to 4 nuclei. They are more often detected in patients with chronic amoebiasis and parasite carriers. They are very stable in the external environment: they remain in feces at room temperature for up to 2 weeks or longer, when frozen to −21°C - no more than 3 months, in water - up to 8 months. When heated to 100°C and boiled, they quickly die. Standard household disinfectants with chlorine have almost no effect on cysts. Soap-cresol preparations, a solution of sublimate 1:1000 and a 3% solution of carbolic acid can affect them [1][3][7][10].

Epidemiology

Amoebiasis is a widespread disease, mainly found in the countries of Southern and Western Africa, Central and South America, as well as in India, China and Korea. In Russia, isolated cases are mainly recorded, mainly in the southern regions, the Caucasus and the Far East. Although recently the incidence in our country has been increasing. This may be due to the influx of migrants from border regions and the development of tourism.

On average, about 50 million cases of amoebiasis are registered annually in the world, of which about 100 thousand end in death. In terms of the number of deaths, this disease ranks third among parasitic diseases. Approximately 90% of cases of the disease are intestinal amoebiasis, the remaining forms are extraintestinal.

The source of infection is a person (patient or carrier). With its feces, amoebas in the form of cysts enter the environment.

The transmission mechanism is fecal-oral. Includes water, food, household contact and sexual (oral-anal) transmission routes. Infection can occur when any substance (water, food, dirt, fingers) that comes into contact with the feces of an infected person or contains some part of it enters the mouth. Mechanical spreaders and carriers can be cockroaches and flies. In extremely rare cases, homosexuals and patients with secondary immunodeficiency may become infected when amoebas enter directly into the wound.

A person with amoebiasis runs the risk of transmitting the infection to family members, but this risk is low, especially if the person follows the rules of personal hygiene: thoroughly washes his hands after using the restroom and before preparing food.

Situations that increase the risk of infection:

- visiting tropical countries with low levels of sanitation;

- interaction with immigrants from tropical countries with poor sanitary conditions;

- neglect of personal hygiene rules;

- consumption of raw, undisinfected water from open sources and the water supply system;

- homosexual contacts;

- presence of mental disorders.

Immunity after an illness is unstable and weakly expressed, repeated infections are possible. Even a large number of antibodies formed, for example in amoebic liver abscesses, do not protect against the progression of amebiasis [1][2][5][6].

Amoebiasis: clinical picture, diagnosis, treatment

ToolkitInterregional Association for Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobial Chemotherapy Institute of Medical Parasitology and Tropical Medicine named after. E.I. Martsinovsky, MMA named after. THEM. Sechenov

Amoebiasis is a parasitic human disease caused by pathogenic strains of Entamoeba histolitica

, is one of the most important health problems in developing countries and one of the most common causes of death from parasitic intestinal diseases.

The guidelines provide basic information about amoebiasis, its clinical manifestations, treatment and prevention. Issues of treatment of invasive and non-invasive amoebiasis are discussed.

For general practitioners, infectious disease specialists, pediatricians, epidemiologists, urologists, obstetricians-gynecologists, clinical pharmacologists.

Authors' team

A.M. Bronstein

Institute of Medical Parasitology and Tropical Medicine named after. E.I. Martsinovsky, Moscow Medical Academy named after. THEM. Sechenov, Moscow, Russia

ON THE. Malyshev

Clinical Infectious Diseases Hospital No. 1, Moscow, Russia

IN AND. Better

Department of Infectious Diseases, Tropical Medicine and Epidemiology, Russian State Medical University, Moscow, Russia

Contact address

- Alexander Markovich Bronstein

103287, Moscow, st. Pistsovaya 10, City Clinical Hospital No. 24 (clinical department of IMPiTM) Tel:/fax: (095)285-2669 Email. mail

Content

- Pathogen parasite: taxonomy, morphology and life cycle

- Clinical forms of invasive amoebiasis

- Intestinal amoebiasis

- Extraintestinal amoebiasis

- Laboratory and instrumental diagnostics

- Treatment

- Prevention

- Bibliography

Amebiasis is a disease caused by pathogenic strains of Entamoeba histolytica

, which are widespread in the world, mainly in countries with tropical and subtropical climates.

The low level of sanitation characteristic of these areas causes a high incidence of amoebiasis. Currently, amoebiasis represents one of the largest medical and social problems for the population of developing countries and is one of the most common causes of death in parasitic intestinal diseases. After malaria, this infection ranks second in the world in the frequency of deaths due to parasitic diseases [1, 2]. About 480 million people in the world are carriers of E. histolytica

, 48 million of them develop colitis and extraintestinal abscesses, and death occurs in 40 thousand - 100 thousand cases [3]. Migration, the deteriorating economic situation of a number of developing countries, and low levels of sanitation contribute to the spread of amoebiasis and, accordingly, an increase in the incidence rate.

In Russia, amoebiasis occurs in the southern regions. At the same time, due to the increasing influx of migrants from the southern regions of near and far abroad countries, an increase in incoming tourism, as well as a significant increase in foreign tourism, including to countries with hot climates, the frequency of cases of amoebiasis among Russian citizens, including residents of Moscow has increased significantly.

Pathogen parasite: taxonomy, morphology and life cycle

7 species of amoebas can be identified from human feces: Entamoeba histolytica

,

Entamoeba dispar

,

Entamoeba hartmanni

,

Entamoeba coli

,

Endolimax nana

,

Iodamoeba butschlii

and

Blastocystis hominis

, but only

E. histolytica

can cause invasive infections in humans.

The previously noted dissonance between the high frequency of E. histolytica

and, at the same time, the relatively low frequency of clinical manifestations, as it turned out, is partly associated with the presence in the

E.histolytica

of two types of amoebas - potentially pathogenic strains

of E.histolytica

, and non-pathogenic

E.dispar

, which can only be distinguished by DNA analysis [4].

In recent years, a sensitive and specific PCR method has been developed, which makes it possible to relatively simply and quickly identify both E. histolytica

and

E. dispar

[5].

At the same time, the question of the difference in pathogenicity of strains within the species E. histolytica

remains unclear.

Using isoenzyme analysis, 9 potentially pathogenic zymodemes of E. histolytica

, and 13 apparently non-pathogenic zymodemes, between which differences in DNA were also identified [6, 7].

E. histolytica

belongs to the genus

Entamoeba

, belonging to the family

Entamoebidae

, order

Amoebida

, class

Lobosea

, superclass

Rhizopoda

, subphylum

Sarcodina

, phylum

Protozoa

.

E. histolytica cysts

enter the gastrointestinal tract with water or food products. In the small intestine, under the action of intestinal enzymes, the cyst shell dissolves and eight mononuclear amoebae are formed. As a result of subsequent divisions, they turn into vegetative luminal stages, trophozoites ranging in size from 10 to 60 microns, on average 25 microns, having a single nucleus, the habitat of which is the lumen of the upper parts of the large intestine. As they move through the intestine, trophozoites transform into one-to-four-nucleated cysts (on average 12 μm in diameter), which are excreted in the feces.

E. histolytica cysts enter the human body

, due to the influence of a number of factors, invasive forms of the parasite are formed. In the development of invasive forms, factors of the parasite and the host are important, such as: intensity of invasion; physicochemical environment of the intestine (nature of mucosal secretion, disturbances of intestinal motility); immunodeficiency; starvation; stress, etc. In particular, the relatively frequent development of invasive forms of amebiasis in pregnant women is noted [1, 8, 9]. There is also evidence that in people infected with HIV, invasive amebiasis develops more often [10, 11].

Invasive or so-called tissue stages of amoebas are larger in size than luminal ones, can phagocytose red blood cells, have proteolytic properties and surface pectins that promote their attachment to the intestinal mucosa [6, 12].

Recently it has been established that the main virulence factor in E. histolytica

are cysteine proteinases that are absent in

E. dispar

. Further research in this direction may contribute to the development of cysteine proteinase inhibitors, which can be used to create new amoebicides [13].

In accordance with the pathomorphological changes and clinical picture, “invasive” amebiasis is distinguished, in which pathological changes develop, and “non-invasive” amebiasis [6].

“Invasive” amoebiasis is characterized by:

- clinical symptoms of an infectious disease;

- the presence of hematophagous trophozoites in feces;

- characteristic changes in the intestinal mucosa during endoscopic studies;

- the presence of specific antibodies detected by serological tests.

“Non-invasive” intestinal amebiasis (this condition is also defined as “carriage” of amoebic cysts) is characterized by:

- asymptomatic;

- absence of hematophagous trophozoites;

- absence of pathological changes during endoscopic examinations;

- lack of specific antibodies.

Only a small proportion of individuals infected with amoebas will develop invasive amoebiasis. In countries where E. histolytica

widespread, 90% of infected individuals have non-invasive amoebiasis, who are thus “asymptomatic carriers” of luminal forms of amoebae, and only 10% of infected individuals develop invasive amoebiasis [1, 2, 3].

Pathological changes and clinical manifestations of invasive amoebiasis vary widely from colitis with mild clinical manifestations to fulminant colitis and amoebic liver abscess. The most common clinical manifestations of invasive amoebiasis are amoebic colitis and amoebic liver abscess, with amoebic colitis occurring 5-50 times more often than amoebic liver abscess [1].

The main causes of death in amoebiasis are liver abscess and fulminant colitis [14, 15, 16].

Clinical forms of invasive amoebiasis

Intestinal amoebiasis

Asymptomatic presence (carriage) of luminal forms of E. histolytica

in the large intestine may persist for many years. However, at any time, luminal forms can transform into tissue forms, causing “invasive” or clinically significant amebiasis.

The primary manifestations of amoebiasis are the formation of small areas of necrosis in the colon mucosa, which can progress to the formation of ulcers. The ulcer can grow not only along the periphery due to the submucosal layer, but also in depth, reaching the muscular and even serous membrane. A deep necrotic process leads to the formation of peritoneal adhesions and is the cause of perforated peritonitis. Amebic ulcers can spread throughout the entire length of the large intestine, but are more often localized in the cecum.

Typical amoebic ulcers are sharply demarcated from surrounding tissues and have jagged edges. At the bottom of the ulcer there are necrotic masses consisting of fibrin and containing amoeba trophozoites. The inflammatory reaction is mild. The necrotic process in the center, undermined and raised edges of the ulcer, reactive hyperemia and hemorrhagic changes around it constitute the most typical features of ulcerations in intestinal amoebiasis.

Along with changes in the mucosa and necrosis, a regenerative process occurs in the intestinal wall, leading to restoration of the defect through the formation of fibrous tissue. Such a process in chronic amoebiasis can lead to the formation of strictures and stenosis of the intestinal lumen, usually in the ascending and descending sections of the large intestine. When a secondary bacterial infection occurs, an exudate containing neutrophils, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and sometimes eosinophils is formed.

When lesions are localized in the rectosigmoid area of the large intestine, the clinical picture may correspond to dysentery syndrome with tenesmus and, relatively rarely, with an admixture of mucus, blood and pus. When lesions are localized in the cecum, constipation is usually observed with pain in the right iliac region, characteristic of the clinical picture of appendicitis (in some cases, appendicitis actually develops). Localization of amoebic lesions in the ileum is much less common [1, 17, 18].

Clinical variants of the course of intestinal amoebiasis

Acute intestinal amebiasis (acute amoebic colitis)

- usually manifests itself in the form of one diarrhea.

amoebic dysentery

syndrome develops : acute onset, cramping abdominal pain, tenesmus, loose stools with blood and mucus. High fever and other systemic manifestations are usually not observed. Young children usually experience fever, vomiting, and dehydration [1, 6, 18].

Fulminant amoebic colitis (fulminant colitis)

. A severe necrotizing form of intestinal amoebiasis, characterized by toxic syndrome, total deep damage to the intestinal mucosa, bleeding, perforation, and peritonitis. More often observed in pregnant women and women in the postpartum period. May develop after administration of corticosteroids. The mortality rate reaches 70% [15, 16, 17].

Protracted intestinal amebiasis (primarily chronic amebiasis, post-dysenteric colitis)

. Characterized by impaired intestinal motility, loose stools, constipation (in 50% of cases) or diarrhea alternating with constipation, pain in the lower abdomen, nausea, weakness, poor appetite. In some cases, chronic intestinal amebiasis is a consequence of amoebic dysentery [1].

Complications of intestinal amoebiasis

- Intestinal perforation

, often in the cecum, less often in the rectosigmoid area, which can lead to peritonitis and abdominal abscess. - Amoebic appendicitis

- Massive intestinal bleeding

due to erosion of a large artery by an ulcer. - Ameboma

is a tumor-like growth in the wall of the large intestine, mainly in the ascending, cecum and rectum. Consists of fibroblasts, collagen and cellular elements. Contains a relatively small number of amoebas. - Amoebic intestinal stricture

is formed by granulation tissue. Strictures are usually single and located in the region of the cecum or sigmoid colon and contain amoeba trophozoites; often asymptomatic; sometimes contribute to the development of constipation and partial intestinal obstruction.

Extraintestinal amoebiasis

Pathological changes in extraintestinal amoebiasis can develop in almost all organs, but the liver is most often affected.

Liver abscess

In patients with amoebic liver abscess, indications of previous intestinal amebiasis are detected only in 30-40% of cases, and amoebae in feces are found in no more than 20% of patients. Amoebic liver abscess develops more often in adults than in children and in males more often than in females [19]. Single or multiple abscesses form more often in the right lobe of the liver. The abscess consists of three zones: the central zone of necrosis, containing liquid necrotic masses mixed with blood, usually sterile (bacterial infection occurs in 2-3% of cases); middle, consisting of stroma and outer zone containing amoeba trophozoites and fibrin.

The clinical picture of amoebic liver abscess is characterized by fever with chills and profuse sweating at night; an increase in the size of the liver and pain in the area of the liver projection, moderate leukocytosis. With large abscesses, jaundice may develop, which is a poor prognostic sign. When the diaphragm is involved in the process, a high position of its dome and limited mobility are revealed; development of atelectasis is possible.

Relatively often (in 10-20% of cases) there is a long-term latent or atypical course of the abscess (for example, only fever, pseudocholecystitis, jaundice) with a possible subsequent breakthrough, which can lead to peritonitis and damage to the chest organs [14, 20].

Pleuropulmonary amoebiasis

It is a consequence of a liver abscess breaking through the diaphragm into the lungs, less often due to hematogenous spread of amoebas. It manifests itself by the development of pleural empyema, abscesses in the lungs and hepatobronchial fistula. Characterized by chest pain, cough, shortness of breath, pus and blood in the sputum, chills, fever, leukocytosis [1, 14].

Amoebic pericarditis

It usually develops due to the rupture of a liver abscess from the left lobe through the diaphragm into the pericardium, which can lead to cardiac tamponade and death [1].

Cerebral amoebiasis

Form of hematogenous origin. Abscesses can be single or multiple; are located in any part of the brain, but most often in the left hemisphere. Usually there is an acute onset and a fulminant course with a fatal outcome [1].

Cutaneous amoebiasis

It occurs more often in weakened and exhausted patients. Ulcers are usually localized in the perianal area, at the site of abscess rupture in the fistula area. In homosexuals, it is possible in the genital area [1].

Laboratory and instrumental diagnostics

The simplest and most reliable method for diagnosing intestinal amoebiasis is microscopic examination of feces to identify vegetative forms (trophozoites) and cysts [21].

Trophozoites are usually detected in patients during the period of diarrhea, and cysts - in formed stool. For this purpose, native preparations are prepared directly from feces and/or from enriched samples.

During primary microscopy, native preparations from fresh fecal samples with saline are examined. Subsequently, to identify amoeba trophozoites, native preparations from fresh fecal samples are stained with Lugol's solution or buffered methylene blue. To identify cysts, native preparations prepared from fresh and/or preservative-treated fecal samples are stained with iodine. Detection of amoebas is more effective when feces are immediately examined after collection.

If the number of parasites in a fecal sample is small, the study of native preparations may not detect them. Therefore, additional enrichment methods should also be used. Ether-formalin precipitation is usually used as an enrichment method. However, the enrichment method can usually only detect cysts, since the trophozoites are deformed. Detection of amoeba cysts alone does not confirm the presence of the disease - invasive amoebiasis. Therefore, the study of native and stained preparations is a mandatory initial stage of microscopic examination, and the use of enrichment methods is indicated in cases where the study of native preparations gives negative results.

If there are doubts about the species of trophozoites and cysts and the need for long-term storage of preparations, for example, for the purpose of sending them to a reference laboratory for expert assessment, permanently colored preparations can be prepared. For these purposes, the trichrome staining method is usually used.

The simplest and most reliable method for diagnosing intestinal amoebiasis is microscopic examination of fresh feces. Microscopy requires a high quality microscope and trained personnel. However, even an experienced laboratory technician may not be able to differentiate non-pathogenic protozoa, leukocytes, macrophages containing erythrocytes or partially digested plant fiber from amoeba trophozoites, as well as identify protozoan cysts. If it is impossible to provide high-quality diagnostics on site, it is possible to preserve feces and then transport them to specialized laboratories [21].

If clinical data indicate possible intestinal damage, recto- or colonoscopy is recommended. During recto- and colonoscopy, it is advisable to obtain a biopsy from the affected areas of the intestine in order to identify amoebas and differential diagnosis, in particular, with carcinoma. These methods can detect the presence of ulcers in the intestines, amoebomas, strictures and other pathological changes. A characteristic feature of changes in amoebiasis is a focal rather than diffuse type of lesion [6, 12].

Diagnosis of extraintestinal amebiasis, in particular liver abscess, is carried out by ultrasonography and computed tomography, which make it possible to determine the location, size and number of abscesses, as well as monitor the results of treatment. X-ray examination reveals a high position of the dome of the diaphragm, the presence of effusion in the pleural cavity, and abscesses in the lungs.

If necessary, aspiration of the abscess contents is carried out. Amoebas are rarely found in the center of necrotic masses, and are usually localized in the outer walls of the abscess. To diagnose amoebiasis, serological tests can be used to detect specific antibodies. These tests are especially useful for diagnosing extraintestinal amoebiasis, since in these cases invasive stages of E. histolytica

usually absent.

Since the administration of corticosteroids for amoebiasis can contribute to a sharp deterioration in the course of the disease, serological diagnosis is also recommended for all patients in whom amoebiasis may be suspected and for whom corticosteroids are planned.

Treatment

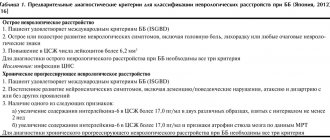

In general, all drugs used to treat amoebiasis can be divided into 2 groups: “contact” or “luminal” (affecting intestinal luminal forms) and systemic tissue amoebicides ( Table 1, 2, 3, 4

) [22].

For the treatment of non-invasive

amoebiasis (asymptomatic “carriers”) use luminal amoebicides (

Table 1

). Luminal amoebicides are also recommended to be prescribed after completion of treatment with tissue amoebicides to eliminate amoebae remaining in the intestine in order to prevent relapses. In particular, there are observations of the development of amoebic liver abscesses in individuals with intestinal amoebicides who received only tissue amoebicides without subsequent administration of luminal amoebicides [1, 14]. In particular, a recurrence of an amoebic liver abscess in a patient 17 years after a successfully treated newly diagnosed liver abscess was described [23].

In conditions where it is impossible to prevent re-infection, the use of luminal amoebicides is inappropriate. In these situations, it is recommended to prescribe luminal amoebicides only for epidemiological indications, for example, to persons whose professional activities may contribute to the infection of others, in particular, employees of food establishments.

Systemic tissue amoebicides are used to treat invasive amoebiasis ( Table 2

). The drugs of choice from this group are 5-nitroimidazoles, which are used both for the treatment of intestinal amebiasis and abscesses of any localization.

Table 1. Luminal amoebocides

Etofamide ( Kythnos

®)

Clefamid*

Diloxanide furoate*

Paromomycin*

* not registered in the Russian Federation

Table 2. Systemic tissue amoebocides

5-nitroimidazoles:

Metronidazole ( Trichopol

®,

Flagyl

®)

Tinidazole ( Tiniba

®,

Fasizhin

®)

Ornidazole ( Tiberal

®)

Secnidazole

Dehydroemetine dihydrochloride for the treatment of invasive amoebiasis and especially amoebic liver abscesses

(not registered in the Russian Federation) and

Chloroquine

(

Table 3

) [7, 31].

Table 3. Chemotherapy drugs used to treat amoebiasis

| Amoebiasis | 5-nitro-imidazoles1 | Luminal amoebocides | Dehydro-emetine2 | Chloroquine3 |

| Non-invasive (carrier) | –/+ | + | – | – |

| Intestinal | + | + | + | – |

| Extraintestinal | + | + | + | + |

1 drugs of the 5-nitroimidazoles group are well absorbed and are usually prescribed orally

. Parenteral (IV) administration of these drugs is used in severely ill patients who cannot take them orally.

2 due to possible severe adverse reactions, primarily cardiotoxic effects, dehydroemetine is a reserve drug and is recommended to be prescribed by intramuscular injection to patients with extensive abscesses; patients in whom previous courses of 5-nitroimidazoles were ineffective, as well as seriously ill patients in whom it is impossible to take drugs per os

.

3 Chloroquine is prescribed in combination with dehydroemetine in the treatment of amoebic liver abscesses.

Table 4. Treatment regimens for amoebiasis

| Intestinal amoebiasis |

| Metronidazole — orally 30 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses for 8-10 days or Tinidazole - up to 12 years - 50 mg/kg/day (max. 2g) in 1 dose for 3 days; over 12 years old - 2 g/day in 1 dose for 3 days or Ornidazole - up to 12 years - 40 mg/kg/day (max. 2 g) in 2 doses for 3 days; over 12 years old - 2 g/day in 2 divided doses for 3 days or Secnidazole - up to 12 years - 30 mg/kg/day (max. 2 g) in 1 dose for 3 days; over 12 years old - 2 g/day in 1 dose for 3 days |

| Amoebic abscess |

| Metronidazole — 30 mg/kg/day in 3 divided doses for 8-10 days or Tinidazole - up to 12 years - 50 mg/kg/day (max. 2 g) in 1 dose for 5-10 days; over 12 years old - 2 g/day in 1 dose for 5-10 days or Ornidazole - up to 12 years - 40 mg/kg/day (max. 2 g) in 2 divided doses for 5-10 days; over 12 years old -2 g/day in 2 divided doses for 5-10 days or Secnidazole - up to 12 years - 30 mg/kg/day (max. 2 g) in 1 dose for 3 days; over 12 years old - 2 g/day in 1 dose for 3 days |

| Alternative treatment regimen for amoebic abscess |

| Dehydroemetine dihydrochloride — 1 mg/kg/day IM (not more than 60 mg) for 4-6 days + At the same time or immediately after completing a course of dehydroemetine, chloroquine - 600 mg base per day for 2 days, then 300 mg base per day for 2-3 weeks |

| After completing a course of 5-nitroimidazoles or dehydroemetine, luminal amoebicides are used to eliminate the amoebae remaining in the intestine: Etofamide — 20 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses for 5-7 days or Paromomycin -1000 mg/day in 2 divided doses for 5-10 days |

In clinically pronounced cases with an appropriate epidemiological history, when a large number of non-pathogenic species of amoebae are found in the feces, it is also recommended to treat with amoebicides, since in these cases there is a high probability of concomitant infection with E. histolytica

[1, 22].

The heterogeneity of the pathological process and clinical manifestations of amoebiasis in different geographical regions, the presence of strains resistant to standard chemotherapy regimens with 5-nitroimidazoles, require varying treatment regimens taking into account the experience accumulated in a particular area [24, 25, 26].

After successful chemotherapy for a liver abscess, residual cavities usually disappear within 2-4 months, but persistence of cavities for up to 1 year is possible.

In seriously ill patients with amoebic dysentery, due to possible intestinal perforation and the development of peritonitis, it is recommended to additionally prescribe antibacterial drugs active against intestinal microflora [22].

Aspiration (or percutaneous drainage) is recommended for large abscess sizes (more than 6 cm), localization of the abscess in the left lobe of the liver or high in the right lobe of the liver, severe abdominal pain and tension in the abdominal wall due to the possible threat of rupture of the abscess, as well as in the absence of effect from chemotherapy within 48 hours of its start. Aspiration is also recommended for abscesses of unknown etiology. If closed drainage is impossible, the abscess ruptures and peritonitis develops, open surgical treatment is performed [14, 27, 28, 29].

When corticosteroids are prescribed in patients with amoebiasis, severe complications can develop, including the development of toxic megacolon. In this regard, if it is necessary to treat residents of endemic areas with a high risk of infection with E. histolytica

, a preliminary examination for amoebiasis is necessary. In case of doubtful results, it is advisable to prescribe amoebicides followed by corticosteroids [1, 17].

Currently, amoebiasis is an almost completely curable disease, subject to early diagnosis and adequate treatment.

Prevention

The source of infection is a person who excretes E.histolytica

. Infection occurs when cysts are ingested in contaminated water and food, usually through uncooked raw vegetables and fruits.

In connection with the above, we can conclude that the main ways to prevent amoebiasis are: improving sanitary conditions, including water supply and food protection; early detection and treatment of sick and asymptomatic carriers; health education [1, 31]. The most effective ways to prevent amoebiasis are to neutralize and remove feces, prevent contamination of food and water, and protect water bodies from fecal pollution (amoeba cysts can survive in water for several weeks). E. histolytica cysts

exceptionally resistant to chemical disinfectants, including chlorination. Boiling water is a more effective method of disinfecting amoebas than using chemicals. Amoebas quickly die when dried, heated to 55°C or frozen.

A direct fecal-oral route of infection through hands or contaminated food is also quite possible [31]. Persons who are asymptomatic carriers of amoebas (in particular, there is evidence that in some regions about 33% of homosexuals are carriers of E. histolytica

), working in food establishments or involved in food preparation at home, should be actively identified and treated, since they are the main sources of infection [1, 30, 31].

Bibliography

- Amoebiasis and its control. Report of a WHO Meeting. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 1985; 63:417-426.

- Cook GC Parasitic infections of the gastrointestinal tract: a worldwide clinical problem. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 1989; 5:126-139.

- Walsh JA Problems in recognition and diagnosis of amebiasis: estimation of the global magnitude of morbidity and mortality. Rev Infect Dis 1986; 8:228-238.

- Huston CD, Petri WA Amebiasis: clinical implications of the recognition of Entamoeba dispar

. Curr Infect Dis Rep 1999; 1:441-447. - Evangelopoulos A., Spanakos G., Patsoula E., et al. A nested, multiplex, PCR assay for the simultaneous detection and differentiation of Entamoeba histolytica

and

Entamoeba dispar

in faeces. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2000; 94:233-240. - Martinez-Palomo A. The pathogenesis of amoebiasis. Parasitol Today 1987; 3:111-118.

- Sargeaunt PG The reliability of Entamoeba histolytica

zymodemes in clinical diagnosis. Parasitol Today 1987; 3:40-43. - Sceto RK., Rockey DC Amebic liver abscess: epidemiology, clinical features, and outcome. West J Med 1999; 170:104-109.

- Shamsuzzama SM, Hague R, Hasin SK, et al. Socioeconomic status, clinical features, laboratory and parasitological findings of hepatic amebiasis patients — a hospital based prospective study in Bangladesh. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2000; 31:399-404.

- Hung SS, Chen PJ, Hsieh SM, et al. Invasive amoebiasis: an emerging parasitic disease in patients infected with HIV in an area endemic for amoebic infection. AIDS 1999; 13:2421–2428.

- Lowther SA, Dworkin MS, Hanson DL Entamoeba histolytica

/

Entamoeba dispar

infections in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in the United States. Clin Infect 2000; 30:955-959. - Espinosa-Cantellano M., Martinez-Palomo A. Pathogenesis of intestinal amebiasis: from molecules to disease. Clin Microbial Rev 2000; 13:318-331.

- Que X., Reed SL Cysteine proteinases and the pathogenesis of amoebiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000; 13:196-206.

- Badalamenti S., Jameson JE, Reddy KR Amebiasis. Curr Trea Options Gastroenterol 1999; 2:97-103.

- Ellyson JH, Bezmalinovic Z., Parks SN, Lewis FR Necrotizing amebic colitis: a frequently fatal complication. Am J Surg 1986; 152:21-26.

- Shukla VK, Roy SK, Vaidya MP, Mehrotra ML Fulminant amebic colitis. Dis Colon Rectum 1986; 29:394-401.

- Abbas MA, Mulligan DC, Ramzan NN, et al. Colonic perforation in unsuspected amebic colitis. Dig Dis Sci 2000; 45:1836-1841.

- Ciftci AO, Karnak 1., Sencak ME, et al. Spectrum of complicated intestinal amebiasis through resected specimens incidence and outcome. J Pediatr Surg 1999; 34:1369–1373.

- Acuna-Soto R., Maguire JH, Wirth DF Gender distribution in asymptomatic and invasive amebiasis. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95:1277–1283.

- Hoffner RJ, Kilaghbian T., Esekogwi VI, Henderson SO Common presentation of amebic liver abscess. Ann Emerg Med 1999; 34:351-355.

- Basic methods of laboratory diagnosis of parasitic diseases. WHO, 1994.

- WHO Model prescribing information. 2nd edition. WHO, Geneva, 1995.

- Shiruma TM, Obata H., Karasawa E., et al. A recurrent case of amebic liver abscess seventeen years after the first occurrence. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 2000; 74:585-588.

- Bassilys S., Farid Z., El-Masry NA, Michail EM Treatment of intestinal E.histolytica

and

G.lamblia

with metronidazole, tinidazole and ornidazole: a comparative study. J Trop Med Hyg 1987; 90:9-12. - Bhatia S., Karnal DR, Oak JL Randomized double-blind trial of metronidazole versus secnidazole in amebic liver abscess. Indian J Gastroenterol 1998; 17:53-54.

- Salles JM, Bechara C, Tavares AM, et al. Comparative study of the efficacy and tolerability of secnidazole suspension (single dose) and tinidazole suspension (two days dosage) in the treatment of amebiasis in children. Braz J Infect Dis 1999; 3:80-88.

- Akgun Y., Tacyildiz lH, Celik Y. Amebic liver abscess: changing trends over 20 years. World J Surg 1999; 23:102-106.

- Hanna RM, Dahniya MH, Badr SS, El-Batagy A. Percutaneus catheter drainage in drug-resistant amoebic liver abscess. Trop Med Int Health 2000; 5:578-581.

- Sharma MP, Rai RR, Acharya SK, Ray JCS, Tandon BN Needle aspiration of amoebic liver abscesses. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1989; 40:384-389

- Gatti S., Cevini C., Bermuzzi AM, et al. Symptomatic and asymptomatic amoebiasis in two heterosexual couples. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 1999; 93:829-834.

- Prevention and control of intestinal parasitic infestations. Ser. tech. report WHO, 1988; 749.

Published: Amebiasis: clinical picture, diagnosis, treatment (KMAH 2001; 3:215)