Among oncological diseases, testicular cancer accounts for about 1.5-2% of all malignant tumors in men. The disease is quite rare, but at the same time aggressive and often causes early cancer mortality. Most patients who experience testicular cancer are over 40 years of age. Most often the tumor develops on one side; bilateral lesions account for only 1-2% of cases. Treatment for testicular cancer traditionally may include radiation and chemotherapy, as well as surgery.

Causes of testicular cancer

Throughout a man's life, there are three age peaks when there is an increased likelihood of developing testicular cancer:

- 10 years. In 90% of cases, the cause of testicular cancer in children is an embryonic benign teratoma, which turns into a malignant form.

- 20-40 years. Testicular cancer can be caused by scrotal trauma, radiation and endocrine diseases such as gynecomastia, hypogonadism, and infertility. The risk of developing the disease is also high with Klinefelter syndrome or Down syndrome.

Another peak age for testicular cancer is after age 60. Heredity may also be a cause. If there have been cases of such a diagnosis among first-degree relatives, then the likelihood of encountering it increases 5 times.

Many patients with this diagnosis have cryptorchidism - failure of the glands to descend into the scrotum. With this pathology, one or both testicles are absent from the scrotum due to a delay in their descent along the inguinal canal. This anomaly often causes testicular cancer in men. It increases the risk of developing such cancer by 10 times.

Description of testicular tumor

Approximately 95% of tumors are germ cell, that is, arising from human primordial germ cells, or “germ” cells. These cells are located in the gonads, the gonads, from which the testicles develop in men. Most germ cell tumors have a malignant course; they are extremely aggressive and capable of rapid and extensive spread of tumor cells from the infectious focus throughout the body through the blood and lymph. With modern treatment approaches, the prognosis has become relatively more favorable than before. If the process is limited to the testicle, then a cure is possible. If the infection spreads throughout the body, then a long-term remission is achieved, that is, a decrease or weakening of symptoms, but no cure occurs. During remission, the patient can gain strength for further treatment, but it is also necessary to be constantly monitored by the attending physician in order to maintain his condition. Remission is long-term, but not durable, which can be caused by the patient’s behavior if he performs prolonged physical activity or leads an unhealthy lifestyle.

The peak incidence of germ cell tumors occurs in the age period from 15 to 34 years. During this period, this is the most common cancer pathology in men, causing 10% mortality from malignant neoplasms. However, if we take into account all age groups, the mortality rate from testicular tumors will be only about 0.15% of all cancer mortality.

In addition to germ cell tumors, there are also non-germ cell tumors. Non-germ tumors are tumors that develop from the sex cord stroma, or gonadal stroma, which in turn consists of Leydig cells and Sertoli cells.

Leydig cell tumor is the most well-known type of sex cord stromal tumor. This formation has clear boundaries and a diameter of up to 5 cm. Such tumors have a large structure and a yellow or yellow-brown tint. In 30% of cases, areas of hemorrhage or necrosis occur. About 10% of Leydig cell tumors are malignant, evidenced by large size, atypical cells, increased rate of division and increase in cell number, necrosis, rapid growth, and spread beyond the testicular parenchyma.

Sertoli cell tumors account for less than 1% of testicular tumors. The average age of people suffering from this disease is 45 years. It is very rare to detect this disease in men under 20 years of age. Sertoli cell tumors have a clear border and are yellow, brown or white. Their diameter is 3.5 cm. Signs of a malignant tumor from Sertoli cells are large size, increased activity of cell division, necrosis, vascular invasion (penetration of tumor cells through blood vessels)

In most cases, non-germ cell tumors have a benign course. However, some of them produce steroids that cause endocrinological symptoms.

What are the symptoms to suspect testicular cancer?

The first symptom of testicular cancer in men is the appearance of a lump that causes pain on palpation. The condition resembles acute epididymitis orchioepididymitis. Pain syndrome is also observed in general in the affected testicle or scrotum. Against this background, there may be a feeling of heaviness in the lower abdomen. As the tumor grows, the scrotum becomes asymmetrical and edema.

Further symptoms and signs of testicular cancer in men are associated with the fact that the tumor metastasizes. The patient has an enlargement of the retroperitoneal lymph nodes. They compress the nerve roots, causing back pain and intestinal obstruction.

If the lymphatic pathways are blocked, pain in the lower extremities may occur. With hormonally active cancer, decreased libido and impotence are observed. Like many cancers, testicular cancer is characterized by sudden weight loss, constant fever and fatigue.

Symptoms of the disease

In the early stages, testicular cancer has no obvious symptoms. The patient may be alerted by heaviness in the scrotum, changes in the size and density of one or both testicles, and asymmetry of the scrotum. If these signs appear, you should consult a doctor for differential diagnosis, diagnosis and, if necessary, treatment. Treatment started in the early period of the disease greatly increases the chances of recovery and increases the prognosis of survival.

Some testicular tumors produce female sex hormones, so a man may notice changes in appearance - enlarged mammary glands, female-type fat deposition (on the hips), as well as impaired potency. Sometimes, more often when a tumor appears in childhood, there is a premature increase in the size of the penis and the appearance of pubic hair, and the duration and frequency of erections increases.

As the tumor grows and spreads to nearby lymph nodes, they enlarge; compression of the ureters and difficulty urinating, swelling of the legs, pain in the lower back and lower abdomen may occur. With the further development of the disease and the appearance of distant metastases, patients are concerned about symptoms associated with disruption of the functioning of those organs to which the tumor has metastasized, intoxication and exhaustion develop.

Types and stages of the disease

A testicular tumor can develop from the stroma or seminiferous epithelium. In the first case, germ cell cancer is diagnosed, and it accounts for 95%, in the second case, non-germ cell cancer. In some cases, mixed neoplasms are diagnosed. Germ cell tumors include:

- embryonal cancer,

- seminoma,

- choriocarcyonoma,

- malignant teratoma.

Non-germinogenic testicular tumors:

- Leydigoma,

- sertolioma,

- sarcoma.

When determining a treatment regimen, the stages of testicular cancer, which are determined by TNM criteria, are of particular importance.

- T1 – the tumor does not extend beyond the boundaries of the testicle and epididymis.

- T2 – the tumor grows into the tunica albuginea.

- T3 – the spermatic cord is affected.

- T4 – the tumor has completely invaded the spermatic cord and scrotal tissue.

Classification by regional metastasis (N):

- N1 – the size of metastases does not exceed 2 cm, only regional lymph nodes are affected.

- N2 – metastases increase and reach a diameter of 5 cm.

- N3 – the size of metastases exceeds 5 cm.

The classification for distant metastasis is designated by the letter M. M1a indicates metastasis to the lungs and non-regional lymph nodes, and M1b indicates tumor spread to other organs.

Forecast

Testicular cancer is highly treatable even in the presence of metastases. The survival rate is quite high, and the chances of a full recovery depend on how early the disease is diagnosed and therapy is started. The prognosis is one of the most favorable among all oncological pathologies.

The extent of the tumor is important for prognosis. Conventionally, all malignant neoplasms of the testicle are divided into three groups:

- localized - do not extend beyond the testicle;

- regional - metastases to neighboring organs and nearby lymph nodes;

- common – metastases in distant lymph nodes and organs.

For localized tumors, the five-year survival rate, provided full treatment is received, reaches 96-99%. With regional – 85-95%, with widespread – 57-73%.

The prognosis for recovery and survival also depends on the type of tumor and the level of tumor markers in the blood after its removal. In general, the earlier treatment is started, the better the prognosis.

How is testicular cancer diagnosed?

A step-by-step diagnosis of testicular cancer in men begins with a consultation with a urologist, who conducts an external examination of the scrotum with diaphanoscopy (tissue x-ray). The list of additional examinations also includes:

- sonography (ultrasound of the scrotum);

- analysis for serum markers;

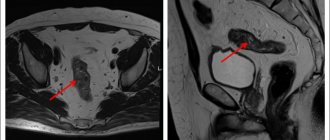

- magnetic resonance and computed tomography;

- scintigraphy.

Blood tests for testicular cancer are aimed at identifying special tumor markers that are sensitive specifically to this type of tumor. A definitive diagnosis can be made with a biopsy. It is usually carried out urgently during diagnostic surgery. If cancer is confirmed, the affected gonad is immediately removed.

In the question of how to determine testicular cancer in men, identifying metastases is important. Distant metastasis can be detected using:

- Ultrasound of the abdominal cavity,

- chest x-ray,

- kidney sonography,

- osteoscintigraphy,

- MRI and CT.

Diagnostics

To make a diagnosis, you must make an appointment with an andrologist or urologist. The examination consists of the following components:

- Examination, palpation of problem areas, interviewing the patient and taking an anamnesis.

- Ultrasound. The effectiveness of ultrasound examination in this case is very high.

- MRI or CT.

- Bone scintigraphy is necessary to detect metastases.

- Blood tests for tumor markers.

- Biopsy through inguinal access.

Interesting fact: one of the tumor markers is hCG. In women, the level of this substance increases during pregnancy. So some types of testicular cancer can be detected in the early stages using a pregnancy test.

Testicular cancer treatment methods and prognosis

Organ-sparing operations for testicular cancer are practiced in cases of bilateral lesions or tumors of a single gland. Testicular resection is performed followed by adjuvant radiation therapy, which is aimed at reducing the risk of relapse. The classic type of surgery performed is orchiectomy. If the lymph nodes are affected, a retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy is additionally performed.

Treatment of testicular cancer in men of childbearing age begins with an examination by a urological oncologist. This is because in such patients, combining surgery with radiation or chemotherapy can lead to infertility. If a man wants to have children in the future, he must first resort to sperm cryopreservation.

Treatment and prognosis of testicular cancer are inextricably linked. At stage T1-T2, about 90-95% of patients recover. With metastases, the prognosis worsens slightly and the survival rate drops to 50%. Therefore, it is so important to see a doctor in time.

If you are concerned about certain symptoms, make an appointment with a urologist to receive qualified help and undergo the necessary examination. All medical services in our center are provided under the compulsory medical insurance policy, so you can undergo testicular cancer treatment for free.

On weekdays you can get an appointment with a urologist on the day of your visit

What kind of observation is required after treatment?

After completion of treatment, it is necessary to undergo periodic examinations to timely detect relapse or progression of the disease. How often you should be examined, as well as the amount of necessary research, will be determined by your doctor, depending on the stage of the disease and the treatment provided. This involves determining the level of tumor markers, chest x-ray, ultrasound, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the abdominal cavity and chest.

Hakobyan Gagik Nersesovich – professor, doctor of medical sciences, oncologist, urologist in Moscow

The appointment is conducted by a doctor of the highest category, urologist, oncologist, doctor of medical sciences, professor. Author of more than 100 scientific papers.

Urological oncology experience – more than 15 years. Helps men and women solve urological and oncourological problems.

Conducts diagnostics, treatment and complex operations for such diagnoses as:

- tumors of the kidneys and upper urinary tract;

- prostate and bladder cancer;

- urolithiasis disease;

- BPH;

- hydronephrosis, ureteral stricture, etc.

Psychological rehabilitation

Removal of a testicle is a powerful psychological trauma for a man. Even despite a favorable prognosis, recovery from a life-threatening disease, preservation of erection and sexual desire, and normal ability to reproduce, many men feel inferior due to the presence of one testicle in the scrotum. Fortunately, today this problem can be easily solved by implanting a silicone testicular prosthesis into the scrotum. The appearance of the scrotum after implantation and the prosthesis itself are completely indistinguishable to the touch from the real organ.

During your consultation, the urologist will answer all your questions in detail.

If you are bothered by difficulty or frequent urination, pain in the lumbar region, blood in the urine, as well as other symptoms (read about what else should alert you here), seek help from a urologist.

Admission includes:

- familiarization of the doctor with the patient’s medical history;

- inspection;

- making a preliminary diagnosis, prescribing tests and necessary procedures.

*If you plan to get tested immediately after your appointment with your doctor, go to the clinic with a full bladder.

Do not delay your visit to the clinic - come for a consultation with a urologist at the State Urology Center in Moscow - the R. M. Fronshtein Urology Clinic of the First Moscow State Medical University named after I.M. Sechenov. Entrust your health to a competent specialist!

Will I be able to have children?

Contrary to popular belief, removal of one testicle does not lead to a significant deterioration in the fertilizing ability of sperm and a decrease in the level of male sex hormones. As mentioned above, half of patients with testicular cancer have reduced sperm quality before surgery and improve after it.

However, adjuvant (post-surgical) treatments significantly reduce fertility. Radiation and chemotherapy worsen the quality of sperm; surgery to remove retroperitoneal lymph nodes leads to disruption of natural ejaculation.

Therefore, before each stage of treatment, including before removal of a testicle, the patient is offered sperm freezing (cryopreservation).

What is testicular cancer and why is it dangerous?

Testicular cancer is a malignant type of tumor, the cells of which are capable of metastasizing to neighboring and distant organs. Like any other malignant tumor, testicular cancer poses a threat to the patient's life.

Testicular cancer comes in several forms:

- seminoma cancer – develops as a benign tumor, does not metastasize;

- nonseminoma cancer – spreads quickly, metastasizes;

- malignant lymphoma - occurs less frequently than the first two forms of the disease, the tumor is formed from lymphoid tissue, grows quickly and metastasizes;

- Sertoli-Leydig tumor is a poorly understood form of cancer that affects adolescents.

Embryonal testicular cancer

In addition to the above forms of testicular cancer, embryonal cancer is also isolated. Its origin begins during the period of intrauterine development. Signs of this disease may appear before the onset of puberty.

This form of cancer is very dangerous; even after successful treatment, there is a high risk of developing infertility. In addition, such a tumor tends to metastasize, even if its size is small.

Materials of congresses and conferences

Testicular cancer: clinical picture and stages of the disease.

William G. Jones Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust, Cookridge Hospital, Leeds, UK

Clinical picture.

Testicular cancer is a relatively rare tumor, and usually practicing doctors rarely encounter this pathology. As a rule, testicular cancer affects men of working age from 15 to 50 years [1]. The clinical picture of the disease consists of symptoms caused by the presence of a primary testicular tumor and metastases, or a combination of them. The most common signs of a primary testicular tumor are pain, enlargement or swelling of the organ with the appearance of a palpable tumor formation in it. These symptoms occur in 80-90% of patients [2]. Only 10% of patients complain of pain, often severe, indicating infringement of tumor masses, bleeding or infarction in the tumor tissue, or concomitant acute epididymitis. Patients often have a history of recent trauma to the scrotal area. Patients may also report that the affected testicle has recently changed in consistency and size, becoming denser, or, less commonly, becoming softer and smaller (due to atrophy). Often patients note a feeling of heaviness in the scrotum or dull pain in the lower abdomen or scrotum area. Often the patient’s sexual partner is the first to discover a mass in the testicle and insist on consulting a doctor. In 5% of cases, the only symptom of the disease may be back pain. This is a very common and nonspecific symptom in this age group, but it may be a manifestation of metastatic testicular cancer [3]. About 3% of patients have signs of gynecomastia, which occurs as a result of the secretion of significant amounts of human chorionic gonadotropin by tumor tissue [4].

Often the symptoms associated with the presence of metastases prevail over the symptoms of testicular damage. Severe back pain may indicate enlargement of the retroperitoneal lymph nodes, which compress the nerve roots, or involvement of the lumbar muscle in the process. Gastrointestinal symptoms and weight loss are common, and sometimes a tumor mass is detected by palpation in the abdominal cavity. The spread of the tumor above the diaphragm can lead to the detection of visible tumor masses in the left supraclavicular region and complaints of shortness of breath and chest pain [5]. Very rarely, patients complain of bone pain resulting from metastatic skeletal lesions. When the central nervous system is involved, symptoms of increased intracranial pressure, epileptiform seizures, or other neurological symptoms appear. More than 50% of patients with nonseminoma and 25% with seminoma have metastases when visiting a doctor, which are clinically manifested in only 10% of cases.

Ultrasound diagnostics can be used for the differential diagnosis of various pathological formations in the scrotum [1,6]. Because testicular cancer has a short cell doubling period (an average of 3 weeks for non-seminoma), the tumor can grow in size very quickly. Therefore, it is especially important to promptly refer such a patient to a specialist. This is especially true for patients with prolonged hydrocele failure to resolve or patients with epididymo-orchitis who have not responded to antibiotic therapy for more than 2 weeks. Differential diagnosis of testicular cancer includes epididymo-orchitis, testicular tuberculosis, granulomatous orchitis, hydrocele, hematocele, hematoma or hernia, as well as gumma and testicular torsion. However, any testicular mass should be considered as a possible testicular cancer, and any patient with suspected testicular malignancy should be immediately evaluated by a urological surgeon or oncologist [1].

Untimely (late) diagnosis.

Delay in diagnosis is rare and usually occurs due to the patient’s delay in visiting a doctor [7-10]. It is clear that late diagnosis leads to the need to treat a more widespread disease and, accordingly, to a worse prognosis. Patients put off visiting a doctor for various reasons: firstly, it is the fear of a sexually transmitted disease (especially in the case of adultery), and secondly, the fear that treatment may disrupt their sexual function. A small proportion of patients are embarrassed to discuss this issue or even allow a doctor to examine them, especially if the doctor is a woman.

Popular educational programs are needed to reduce public ignorance on this issue and reduce the incidence of late diagnosis [11]. They should explain the seriousness and potential risk of this disease in men aged 15 to 50 years, teach self-examination techniques and show the real possibility of cure if they consult a doctor in a timely manner. On the other hand, doctors should always remember that any tumor formation in the testicle should be regarded as malignant until proven otherwise. An example is the reporting of a cyclist who achieved victory in last year's Tour de France after being cured of testicular cancer. Information about this case helped reduce public ignorance and social taboos against discussing the issue in the press.

Examination of the patient.

The patient's examination begins with careful palpation of the testicle. Normally, the testicles have a dense but homogeneous consistency and are quite mobile. The epididymis is usually palpated as a separate formation. A testicular tumor is usually suspected when the testicle becomes denser and increases in size. Less commonly, the testicle becomes atrophic and decreases in size. As the examination continues, palpation of the groin, abdomen and supraclavicular areas is performed in order to exclude metastatic lesions of the lymph nodes in these areas. The examination would not be complete without a clinical examination of the chest organs and examination of the mammary glands.

Ultrasound examination (ultrasound) of the scrotum area should be included in the examination of a patient with suspected testicular malignancy and can be easily performed in any hospital. Ultrasound is a non-invasive, relatively inexpensive method that can distinguish normal testicular tissue from tumor formation in almost 100% of cases. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a more accurate method, but cannot be used in routine practice due to the high cost of the method. However, in some cases, MRI can be used to resolve discrepancies between ultrasound and physical examination findings. Orchofuniculectomy and histological examination of the obtained material clarify the diagnosis of testicular tumor. This procedure allows you to remove the testicle without damaging the tunica albuginea, which avoids local metastasis or local recurrence.

Testicular cancer staging.

The stage of testicular cancer is determined according to the degree of spread of the process before removal of the primary tumor. As is known, the staging of various malignant tumors differs in different anatomical regions. Testicular cancer metastasizes by hematogenous and/or lymphogenous route. Metastasis occurs through the lymphatic vessels into the retroperitoneal space, mainly in the kidney area. Right-sided tumors preferentially metastasize to the aortocaval, precaval, and right para-aortic lymph nodes, whereas left-sided testicular tumors tend to spread to the left para-aortic and preaortic lymph nodes. About 1/5 of tumors of the right testicle can also metastasize contralaterally to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes on the left, which is not typical for tumors of the left testicle. Subsequently, metastases spread to the lymph nodes of the renal hilum and legs of the diaphragm. Supradiaphragmatic metastasis occurs through the thoracic duct, reaching the upper mediastinal and supraclavicular lymph nodes. Penetration of cancer cells (emboli) through the supraclavicular vein into the pulmonary bloodstream leads to the appearance of pulmonary metastases. Direct lymphatic spread through the diaphragm may lead to metastases in the posterior and inferior mediastinum. Hematogenously, testicular cancer metastasizes to the lungs, liver, bones, bone marrow, and skin. This is more common in nonseminomas than in seminomas.

The task of staging the process is to determine the extent and nature of metastases, which further determines the patient’s treatment tactics. The level of serum markers hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin), AFP (alpha fetoprotein) and LDH (lactate dehydrogenase) should be determined in the pre- and postoperative period, and subsequently at weekly intervals. The situation when, after surgery, the level of AFP and hCG does not normalize, indicates the prevalence of the disease, which makes these serological tests justified. In such a clinical situation, a CT scan (the advantages of MRI have not yet been proven) of the chest, abdominal cavity and pelvis should be performed in the near future after orchofuniculectomy. CT or MRI of the brain is indicated for patients with multiple metastatic foci in the lungs or with a postoperative hCG level of more than 10,000 IU/ml, because they have a high risk of cerebral metastases.

Stages of testicular cancer before 1997

Bypassing the general agreement that stage I disease is the stage when only the testis is affected, different classifications were used in the world before 1997. This inconsistency between individual centers did not allow analysis of the results of various non-randomized studies. With the advent of effective chemotherapy regimens, it became clear that the success of treatment and, accordingly, the prognosis of the disease depend on the extent of the disease. The weight of the metastatic tumor, the number of groups of lymph nodes involved, and the location of metastases are important for prognosis. An increased level of expression of serum tumor markers AFP and hCG also began to be considered as an indicator of the biological aggressiveness of the tumor. There have been many attempts, notably by the EORTC and MRC [13,14], to define prognostic groups of patients. The main task was to develop a classification that would determine the patient's prognosis and the appropriate therapeutic tactics.

Classification.

The anatomical classification proposed by the Royal Marsden Hospital (UK) has been used in the United Kingdom and Europe for more than 20 years (Table 1) [15]. This system reflected the involvement of lymph nodes of various locations in the pathological process, the size and number of pulmonary metastases. Extrapulmonary visceral metastases were classified as stage IV of the disease. This classification continues to be used, although it has recently been modified somewhat. It remains relevant for the management of seminomas and other, rarer types of tumors, such as Leydig cell tumor. Attempts to create a classification with prognostic value led to the creation of a new classification, IGCCCG, in 1997 [16]. This classification was created through the collaboration of clinicians from 10 countries who summarized the experience of treating a large group of patients (5202 patients with non-seminoma testicular tumor and 660 patients with seminoma germ cell tumor) using combinations based on platinum derivatives. A multivariate analysis of the prognostic factors of these patients for survival and progression was performed. As can be seen from Table 2, 3 prognostic groups of patients were identified (good, intermediate and poor prognosis). The three most important prognostic factors were: serum marker levels (including LDH as a prognostic indicator but not a specific marker), the presence or absence of pulmonary metastases, the presence or absence of extrapulmonary visceral metastases, and the presence of extragonadal mediastinal tumor. It is important to emphasize that the group of patients with testicular seminoma included patients for the most part (about 80%) who had stage I or II of the disease and who received radiation therapy more often than chemotherapy. The International Union Against Cancer (UICC) recognized the importance of this work and included this classification in the 5th edition of the international TNM classification in 1997 [17]. The classification summary is presented in Table 3. The stages of the disease are presented in Table 4. This new classification has proven to be a significant aid to clinicians when planning therapy for patients with germ cell tumors.

Symptoms of the disease that are not associated with the main tumor in the testicle.

Backache. Tumor formation in the abdomen.

Patients with testicular cancer metastases to the retroperitoneum suffer from back pain, gastrointestinal disorders (constipation or other symptoms). The patient may not notice a tumor formation in one of the testicles, and if he does notice, then, as a rule, he does not attach much importance to it. Such patients, as a rule, complain of weakness, rapid mental and physical fatigue. Upon further examination, it may turn out that there are tumor metastases in other organs. If the patient is in serious condition, the question of starting chemotherapy before removal of the primary tumor becomes relevant. In such cases, the diagnosis of testicular germ cell tumor is made based on elevated tumor markers.

Extragonadal retroperitoneal germ cell tumors.

A primary extragonadal tumor with an undetectable tumor in the testicle in most cases still turns out to be secondary. Upon careful questioning of the patient's history, there is evidence of mild testicular enlargement over a period of several days or weeks in the past, often occurring many months or even years ago. The mechanism of development of extragonadal tumors in this situation is as follows: the growth of the testicular tumor was so rapid that it outpaced its own angiogenesis, and the tissue of the testicular tumor underwent necrosis, having, however, managed to give metastatic screenings to the retroperitoneal space or mediastinum. Often in such cases, a histological examination after orchofuniculectomy may reveal a scar in the testicle. Upon examination, such a testicle is atrophic, and ultrasound may detect pathology in the testicle [18].

Germ cell tumors of the mediastinum.

About 5-7% of all germ cell tumors develop outside the gonads - in the mediastinum or retroperitoneum. While most retroperitoneal extragonadal tumors are in fact gonadal in origin, mediastinal extragonadal tumors are more often truly extragonadal and have a different nature and biological characteristics from true testicular tumors [19]. For extragonadal nonseminoma germ cell tumors of the mediastinum, the prognosis is completely different, and according to the latest IGCCCG classification, this group of tumors is classified as poor prognosis. Primary seminomas, which account for approximately 30-40% of mediastinal malignancies, have a good prognosis and respond well to standard chemotherapy. A large tumor volume in the mediastinum in such patients is usually discovered incidentally during examination for complaints of shortness of breath or discomfort (pain) in the heart area. Young patients with signs of gynecomastia should undergo chest radiography to exclude a tumor producing hCG.

Other metastatic manifestations.

Patients with aggressive disseminated testicular cancer (usually nonseminoma with trophoblastic elements) may have metastases to any location: brain, liver, bones, bone marrow, skin, lymph nodes of the chest and abdomen, head and neck. Sometimes the diagnosis is made based on a biopsy of material from these lesions. Very often, morphological interpretation is difficult, especially in the case of a tumor with a low degree of differentiation. Morphologists often give the answer “metastases of adenocarcinoma from an undetected primary site.” Therefore, in any young patient with metastatic manifestations of the above localizations, a differential diagnosis with a testicular germ cell tumor should be made. AFP and hCG levels can provide useful information in this situation. When treating such a patient, even in the absence of clear data in favor of this diagnosis, it is necessary to consider the prospect of chemotherapy with the inclusion of platinum drugs.

Table 1.

Royal Marsden Hospital classification [15]

| Stages | |

| I IM | No evidence of disease outside the testicle Increased markers only |

| II IIA IIB IIC IID* | Involvement of lymph nodes below the diaphragm Maximum size Maximum size 2-5 cm Maximum size >5 Maximum size >10 cm |

| III | Involvement of lymph nodes above and below the diaphragm Retroperitoneal lymph nodes A, B, C, as above Medistinal lymph nodes M+ Cervical lymph nodes N+ |

| IV | Visceral metastases Retroperitoneal lymph nodes as in stage II Medistinal or cervical lymph nodes as in stage III Metastases to the lungs: - L1 - L2 multiple metastases with a maximum size - L3 multiple metastases with a maximum size >2 cm Metastases in the liver H+ Metastases to other organs and tissues, please specify additionally |

Table 2.

IGCCC classification. [16]

| Nonseminoma tumors | Seminoma |

| Good prognosis if all signs are present: | |

| Testicular tumor/extragonadal retroperitoneal Metastases to lymph nodes and/or lungs AFP hCG LDH 56% of all patients with nonseminomas 5-year survival rate 92% | Any location of the primary tumor Metastases to the lymph nodes and/or lungs Normal AFP Any hCG Any LDH 90% with metastatic seminoma 5-year survival 86% |

| Moderate prognosis if all signs are present: | |

| Testicular tumor/extragonadal retroperitoneal Metastases to lymph nodes and/or lungs AFP * 1000 and * 10000 ng/ml or CG * 5000 U/L or * 50000 U/L or LDH* 1.5 norms * 10 norms 28% of all patients with non-seminomas 5- summer survival rate 80% | Any location of the primary tumor Metastases to the liver, bones, brain Normal AFP Any hCG Any LDH LDH 10% seminomas 5-year survival rate 73% |

| Poor prognosis if at least one sign is present: | |

| Extragonadal tumor of the mediastinum Metastases to the liver, bones, brain AFP>10,000 ng/ml or hCG>50,000 U/l or LDH>10 normal 16% of all patients with nonseminomas 5-year survival rate 48% | Patients with seminomas do not qualify for a poor prognosis |

Table 3.

1997 TNM classification [17]

| Testicle | |

| PTis pT1 pT2 pT3 pT4 | Intratubular tumor Testis and epididymis, no invasion of venous and lymphatic vessels Testicle and epididymis, there is invasion of venous and lymphatic vessels Tumor invades the cord Tumor invades the tunica albuginea |

| Retroperitoneal lymph nodes | |

| N1 N2 N3 | >2 >5 cm |

| Distant metastases | |

| M1a M1b | Metastases to lymph nodes above the diaphragm and/or lungs Metastases to the liver, bones, brain |

Table 4.

Stage distribution according to TNM classification, 1997. [17]

| Stages | T | N | M | Markers |

| Stage 0 | pTis | NO | M.O. | SO, SX |

| Stage I | pT1-4 | NO | M.O. | SX |

| Stage IA | pT1 | NO | M.O. | SO |

| Stage IB | pT2 | NO | M.O. | SO |

| pT3 | NO | M.O. | SO | |

| pT4 | NO | M.O. | SO | |

| Stage IS | any pT/TX | NO | M.O. | S1-3 |

| Stage II | any pT/TX | N1-3 | M.O. | SX |

| Stage IIA | any pT/TX | N1 | M.O. | SO |

| any pT/TX | N1 | M.O. | S1 | |

| Stage IIB | any pT/TX | N2 | M.O. | SO |

| any pT/TX | N2 | M.O. | S1 | |

| Stage IIC | any pT/TX | N3 | M.O. | SO |

| any pT/TX | N3 | M.O. | S1 | |

| Stage III | any pT/TX | any N | M1, M1a | SX |

| Stage IIIA | any pT/TX | any N | M1, M1a | SO |

| any pT/TX | any N | M1, M1a | S1 | |

| Stage IIIB | any pT/TX | N1-3 | M.O. | S2 |

| any pT/TX | any N | M1, M1a | S2 | |

| Stage IIIC | any pT/TX | N1-3 | M.O. | S3 |

| any pT/TX | any N | M1, M1a | S3 | |

| any pT/TX | any N | M1b | any S |

Tumor markers - S

| LDH | CG (mIU/ml) | AFP (ng/ml) | ||

| SX | tumor markers were not determined or unknown | |||

| S0 | tumor markers are within normal limits | |||

| S1 | S2 | 1.5 – 10 x ULN* | 5000 — 50000 | 1000 — 10000 |

| S3 | >10 x ULN* | >50000 | >10000 | |

* ULN - upper limit of normal

Bibliography.

1. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Guidelines on the management of adult testicular germ cell tumors. Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. Edinburgh, 1998.

2. Cancer Research Campaign. Factsheet 16 1998: Testicular Cancer - UK. London, CRC, 1998.

3. Cantwell BMJ, Macdonald I, Campbell S, Millward MJ, Roberts JT. Back pain delaying diagnosis of metastatic testicular tumors. Lancet 1989, ii, 739-740.

4. Rustin GJ, Vogelzang NJ, Sleiffer DT, Nisselbaum JN. Consensus statement on circulating tumor markers and staging patients with germ cell tumors. In: Newling DWW, Jones WG (eds): EORTC Genitourinary Group Monograph 7: Prostate and Testicular Cancer. Wiley-Liss, New York. Prog Clin Biol Res 1989; 357: 277-284.

5. Kennedy BJ. Testis Cancer: Clinical signs and symptoms. In: Vogelzang NJ, Scardino PT, Shipley WU, Coffey DS. (eds). Comprehensive Textbook of Genitourinary Oncology. (2nd Edition). Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2000. pp. 877-879.

6. Thomas G, Jones W, van Oosterom A, Kawai T: Consensus statement on the investigation and management of testicular seminoma 1989. In: Newling DWW, Jones WG (eds): EORTC Genitourinary Group Monograph 7: Prostate and Testicular Cancer. Wiley-Liss, New York. Prog Clin Biol Res 1989; 357: 285 – 294.

7. Jones WG, Appleyard I. Delay in diagnosing testicular tumors. Br Med J 1985, 290:1550.

8. Thornhill JA, Fennelley JJ, Kelly DG, Walsh A, Fitzpatrick JM. Patients delay in the presentation of testis cancer in Ireland. Br J Urol 1987, 59:447.

9. Medical Research Council Working Party on Testicular Tumors. Prognostic factors in advanced non-seminomatous germ-cell testicular tumors: results of a multicentre study. Lancet 1985, i: 8-12.

10. Chilvers C, Saunders M Bliss J, Nicholls J, Horwich A. Influence of delay on prognosis in testicular teratoma. Br J Cancer 1989, 59:126-128.

11. Jones WG. Testicular cancer. Br Med J 1987, 295:1488.

12. Stoter G, Sylvester R, Sleijfer DT, et al: Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in patients with disseminated nonseminomatous testicular cancer: Results from an EORTC multiinstitutional phase III study. Cancer Res 1987; 47: 2714 -2718.

13. Mead GM, Stenning SP: Prognostic factors in metastatic non-seminomatous germ cell tumors: the Medical Research Council studies. Eur Urol 1993;23:196-200.

14. Mead GM, Stenning SP, Parkinson MC et al: The Second Medical Research Council study of prognostic factors in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Medical Research Council Testicular Tumor Working Party. J Clin Oncol 1992; 10:85-94.

15. Peckham MJ: Investigation and staging: general aspects and staging classification; in Peckham M (ed): The management of Testicular Tumors. Edward Arnold, London, 1971, pp. 89 - 101. 19.

16. The International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group: International Germ Cell Consensus classification: A prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. J Clin Oncol 1997; 15: 594 – 603.

17. Sobin LH, Wittekind Ch, (eds): TNM classification of Malignant Tumors (UICC - International Union Against Cancer). Wiley-Liss, New York, 1997, pp 174 - 179

18. Azzopardi JG, Mostofi FK, Theiss EA. Lesions of tests observed in certain patients with widespread choriocarcinoma and related tumors. Am J Pathol 1961, 38:207-225.

19. Nichols CR. Mediastinal Germ Cell Tumors. In: Jones WG, Appleyard I, Harnden P, Joffe JK. (eds). Germ Cell Tumors IV. John Libbey, London, 1998. pp. 197-201