Obstetric hemorrhage is a leading cause of maternal mortality in many countries and a leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality. The etiological factors of bleeding during pregnancy depend on the gestational age.

The most common causes of bleeding in the first half of pregnancy are spontaneous abortions, ectopic pregnancy and even physiological pregnancy. Bleeding in the third trimester of pregnancy is observed in 3-4% of cases and can have obstetric and non-obstetric causes. Obstetric hemorrhages can occur antepartum and postpartum. The main causes of obstetric hemorrhage in the third trimester of pregnancy are placenta previa (20% of all cases of obstetric hemorrhage) and premature abruption of a normally located placenta (30% of cases).

- Placenta previa

- Premature placental abruption

- Hemorrhagic shock

- Uterine rupture

- Rupture of fetal vessels

Placenta previa

Terminology . Placenta previa occurs due to abnormal implantation above the internal cervical os. There are several types of placenta previa:

Complete placenta previa - the placenta completely covers the internal os.

Partial placenta previa - the placenta partially covers the internal os.

Marginal placenta previa - the edge of the placenta reaches the edge of the internal os.

Low placental attachment (low placentation) - the placenta is located in the lower uterine segment, but does not reach the edge of the internal os.

Bleeding with placenta previa occurs due to partial detachment of small sections of placenta during normal development and thinning of the lower segment of the uterus in the third trimester of pregnancy.

Bleeding from placenta previa can become profuse and lead to hemorrhagic shock, maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. Perinatal mortality due to this pathology is 10 times higher than in the general population. A significant portion of the risk to the fetus associated with placenta previa is preterm delivery (60% of perinatal mortality cases), as well as other associated fetal complications.

Complications from the fetus with placenta previa

- Premature birth and its complications

- Premature rupture of membranes during premature pregnancy

- Intrauterine growth restriction

- Anomalies of fetal position and presentation

- Vaso previa of the umbilical cord

- Congenital anomalies

previa can be complicated by pathological invasion of the placenta into the uterine wall:

1) placenta accreta - pathological invasion of the placenta into the superficial layer of the myometrium with complete or partial absence of the basal decidua;

2) adult placenta - pathological invasion of the placenta throughout the entire thickness of the myometrium;

3) sprouted placenta - pathological invasion of the placenta with through penetration into the myometrium and perimeter, sometimes with penetration into nearby structures (bladder, etc.).

Placenta accreta leads to the inability of the placenta to separate from the uterine wall after birth, which can lead to massive bleeding and shock, hence maternal morbidity, disability and mortality. About two-thirds of patients with placenta previa and accompanying placenta accreta require a hysterectomy at birth (postpartum hysterectomy).

Other placental abnormalities that may cause antepartum hemorrhage include the rarer conditions:

Shaft-like placenta - the membranes double behind its edge, forming a dense ring around the periphery of the placenta. Often associated with premature placental abruption.

Blanket-shaped placenta - the fetal vessels pass between the amnion and chorion, away from the edge of the placenta, so they are exposed and more susceptible to compression and injury.

A reserve placenta is an additional portion of the placenta that is implanted at some distance from the rest of the placenta. The fetal vessels may pass between two parts of the placenta, possibly over the cervix, leaving them exposed and increasing the risk of damage.

Vaso previa of the umbilical cord is a membrane-like attachment of the umbilical cord when the fetal vessels pass over the internal os.

Epidemiology

Placenta previa occurs in 0.5% of pregnancies (1,200 births) and accounts for 20% of cases of antepartum hemorrhage. Placenta previa is associated with placenta accreta in 5-15% of cases. The risk of placenta accreta increases in patients with a previous cesarean section (25-30%), especially with a repeat previous cesarean section (50-65%).

Pathogenesis

Anomalies of placentation are the consequence of phenomena that interfere with the normal migration of the placenta during the development of the lower uterine segment as pregnancy progresses.

Factors that contribute to the development of placenta previa

- Previous caesarean section

- Previous uterine surgery (myomectomy)

- Abnormalities of the uterus

- Repeated births

- Multiple pregnancy

- Erythroblastosis

- Smoking

- History of placenta previa

- Mother's age is more than 30 years

Previous abnormal placental implantation and previous cesarean section increase the risk of abnormal placentation in subsequent pregnancies. Previous uterine surgery (myomectomy), uterine abnormalities, repeat births, older maternal age, smoking, and a history of placenta previa are also risk factors.

On the other hand, low placental attachment and even marginal presentation are not uncommon during routine ultrasound examinations in the second trimester of pregnancy. Most of these cases regress spontaneously (the phenomenon of “migration” of the placenta during the third trimester of pregnancy with the development of the lower uterine segment).

Clinic

Pregnant women with placenta previa develop sudden, profuse vaginal bleeding. The first episode of bleeding usually occurs after 28 weeks of gestation. During this period, the lower uterine segment expands and thins, disrupting the connection between the placenta and the uterine wall and causing bleeding. In some cases, patients may develop hematuria or rectal bleeding.

Objective examination

If placenta previa is suspected, vaginal examination is contraindicated due to the risk of increasing the area of placenta separation during digital examination and the development of catastrophic bleeding. Most of these patients have preliminary results of an ultrasound examination, which indicates the presence of placenta previa.

In the absence of ultrasound equipment and if placenta previa is suspected, a careful vaginal examination is performed when the operating room is ready for urgent surgery. During a vaginal examination, soft, spongy tissue may be detected near or in the area of the internal os. Due to the increase in vascularization, when examining the cervix in speculum and digital examination, pronounced varicose veins of the lower uterine segment or cervix can be seen.

Diagnostics

The diagnosis of placenta previa should be determined by ultrasound (diagnostic accuracy >95%). If the diagnosis is made before the beginning of the third trimester of pregnancy, ultrasound monitoring (a series of ultrasonographic studies) is prescribed to monitor placental migration. Transvaginal sonography should not be performed in patients with confirmed or suspected placenta previa.

If ultrasound is performed with a full bladder, placenta previa may be overdiagnosed due to compression of the lower uterine segment.

Treatment

In the third trimester of pregnancy, patients with placenta previa are prescribed strict bed rest, sexual intercourse is prohibited, and usually hospitalized after the first episode of spotting.

The development of labor, fetal hypoxia and increased bleeding are indications for urgent cesarean section, regardless of the gestational age of the fetus (according to vital indications from the mother). With mild bleeding and immaturity of the fetus, active expectant management is possible. About 70% of patients with placenta previa have recurrent episodes of bleeding and require delivery before 36 weeks of gestation. For patients in whom labor can be delayed until 36 weeks' gestation, amniocentesis is performed to determine the maturity of the fetal lungs. If sufficient lung maturity is confirmed, a cesarean section is performed between 36 and 37 weeks of gestation.

The doctor’s algorithm for placenta previa includes the following measures:

1. Stabilization of the patient’s vital functions (hospitalization, catheterization of central or peripheral veins, intravenous infusion therapy to normalize hemodynamics, fetal monitoring). Studies of blood group, Rh factor, coagulogram parameters (prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen, fibrinogen degradation products).

Rh-negative patients undergo a Kleiner-Betke test for the presence of fetal red blood cells (the degree of fetomaternal transfusion determines the number of doses of anti-Rhesus immunoglobulin required to prevent alloimmunization).

2. Preparation for massive bleeding. Expectant management, provided the patient’s condition is stable, involves hospitalization and strict bed rest. Blood substitutes (Refortan, etc.), blood (at least two bottles), plasma are prepared, and compatibility tests are carried out.

3. Preparation for premature birth. When the gestation period is less than 34 weeks, dexamethasone or betamethasone is prescribed to accelerate the maturation of the fetal lungs. To continue pregnancy, it is possible to use tocolysis with β-adrenergic agonists.

Bleeding during pregnancy and childbirth

Groshev S., 6th year medical student. dept. honey. Faculty of Osh State University, Kyrgyz Republic; Israilova Z.A., Assistant, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Common data.

Obstetric hemorrhage has always been the leading cause of maternal mortality, so knowledge of this complication of pregnancy is mandatory for any person with a medical diploma.

The severity of blood loss depends on individual tolerance to blood loss, premorbid background, obstetric pathology and method of delivery. Features of the development of blood loss in various obstetric pathologies are different.

The source of acute massive blood loss in obstetric practice can be:

- premature detachment of a normally located placenta;

- placenta previa;

- bleeding in the afterbirth and early postpartum period;

- damage to the soft tissues of the birth canal (ruptures of the body and cervix, vagina, genitals);

- damage to vessels of parametric tissue with the formation of large hematomas.

Features of the state of the hemocoagulation system during physiological pregnancy.

According to the literature and our research, in the third trimester of physiological pregnancy there is an increase in the total activity of blood coagulation factors that make up the internal pathway of hemostasis activation - VIII, IX, X, XI, XII and as a manifestation of this, a shortening of chronometric tests (APTT, AVR) (table) .

The level of fibrinogen at the end of the above trimester increases by 20-30% (compared to the average normative values), and the increase in the number of factors that make up the external pathway of blood coagulation activation is insignificant, as evidenced by the data of the prothrombin complex (PTI on average 100–110%).

The final stage of coagulation, namely the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin, corresponds to standard values in women outside pregnancy. The level of soluble fibrin-monomer complexes before birth is increased by an average of 1.5 times compared to the norm, and in the first day of the postpartum period their number can increase by an average of 50% of the initial value. This level of RFMC persists for 3–4 days and tends to decrease only on days 6–7 of the postpartum period.

Table. Dynamics of hemostasis parameters during physiological pregnancy

| Hemostasis tests | Research stages | |||

| Before giving birth | 1 day | 3 days | 5 days | |

| Ht | 0,31±0,01 | 0,31±0,01 | 0,31±0,01 | 0,32±0,01 |

| PTI, % | 102,0±0,9 | 102,1±0,6 | 101,7±0,6 | 103,0±0,8 |

| TV, sec | 14,1±0,2 | 14,3±0,2 | 14,1±0,2 | 14,6±0,2 |

| TV, donor, sec | 14,7±0.1 | 15,1±0,1 | 14,9±0,1 | 15,2±0,1 |

| ABC | 1,99±0,5 | 1,89±0,5 | 2,11±1,3 | 2,38±1,4 |

| APTT, sec | 35,5±0,8 | 33,7±0,8 | 34,5±0,4 | 35,9±0,6 |

| APTT control, sec | 38,8±0,3 | 38,9±0,3 | 37,9±0,2 | 38,1±0,4 |

| OFT, mg% | 9,1±1,1 | 14,2±1,2 | 12,8±1,5 | 7,3±0,8 |

| HZF, min | 11,6±0,9 | 28,2±3,5 | 29,7±3,5 | 17,0±2,4 |

| Fibrinogen, g/l | 3,6±0,1 | 3,8±0,2 | 3,9±0,2 | 3,7±0,1 |

| Platelets, thousand | 233±8,4 | 247±13,1 | 295±12,2 | 283±11,2 |

| AT III, % | 103,9±3,6 | 96,1±1,9 | 97,1±2,4 | 97,6±2.1 |

| PDF, µg/ml | 6,3±1,2 | 8,8±1,1 | 4,0±0,7 | 3,2±0,5 |

| PDF, control | 3,3±0,3 | 2,8±0,3 | 3,0±0,3 | 2,8±0,1 |

| LIS, sec | 89,0±2,5 | 98,3±3,1 | 96,2±4,2 | 84,7±2,3 |

| LIS control, sec | 84,2±0,6 | 80,5±1,1 | 85,6±2,8 | 80,8±1,8 |

| IRP, % | 96,7±2,1 | 83,1±3,4 | 90,9±4,5 | 96,1±3,5 |

| D-dimers, ng/l | Neg. | Neg. | Neg. | Neg. |

| Aggregation with ADP, sec | 22,0±1,1 | 20,0±0,3 | 23,0±1,0 | 24,0±1,1 |

| Aggregation with ADP (control), sec | 28,3±0,4 | 27,9±0,3 | 28,4±0,5 | 28,4±0,4 |

This confirms the fact of increased activity of the coagulation component of hemostasis and thrombinemia.

In the vascular-platelet component of hemostasis, there is an increase in the aggregation capacity of platelets by 20–30%, with their number being normal.

Due to the high rate of fibrinogen metabolism in the body of pregnant women, there may be a slight increase in early PDF according to the clamp test, in the absence of D-dimers (late products of fibrin degradation) against the background of normal plasminogen concentration. These changes are regarded as moderate activation of fibrinolysis.

The level of AT-III in the labor and postpartum periods remains within the normative values.

Despite the increased activity of the main procoagulants during physiological pregnancy, pathological activation of hemostasis is not detected - this is achieved as a result of the balanced and compensated work of all parts of the hemostatic system, which is a unique feature during pregnancy.

Thus, physiological changes in the hemostasis system are manifestations of the general circulatory adaptation of the pregnant woman’s body to the gestational process, which contributes to effective hemostasis, however, these physiological changes create the background for the failure of adaptation mechanisms in any critical situation during pregnancy and childbirth.

Methods for determining the volume of blood loss.

There are several methods for determining the amount of blood loss, the reliability of which varies. There are direct and indirect methods for assessing blood loss.

Direct methods for assessing blood loss:

- colorimetric

- gravimetric

- electrometric

- gravitational - based on changes in hemoglobin and hematocrit.

Indirect methods:

- assessment of clinical signs;

- measuring blood loss using graduated cylinders or visually;

- determination of blood volume, hourly diuresis, composition and density of urine.

The first, most common method is to collect blood released from the genital tract into a basin and then measure its volume in a graduated flask with a capacity of 1-2 liters. To the amount of blood poured out in this way is added the mass of blood poured onto the padding diapers; it is determined by the difference in the mass of the dry padding diaper and the one moistened with blood.

The second method is to determine the percentage of blood lost from the mother’s body weight before childbirth. Blood loss up to 0.5% is usually physiological; blood loss of 0.7-0.8% or more is usually pathological and can cause symptoms of decompensated blood loss.

A more accurate assessment of the amount of blood loss can be made using the spectrophotometric method, but its main drawback is the duration of execution (over 20 minutes), meanwhile, the speed of determining the volume of lost blood is of vital importance in case of massive, acute blood loss.

To determine the amount of blood loss, you can use a combination of clinical signs and hemodynamic parameters . They are divided into three degrees of severity:

- I degree of severity - weakness, tachycardia - 100 beats per minute, pale but warm skin, systolic blood pressure (SBP) not lower than 100 mmHg, hemoglobin 90 g/l or more;

- II degree of severity - severe weakness, tachycardia - more than 100 beats per minute, SBP 80-100 mm Hg, moist skin, CVP below 60 mm H2O, hemoglobin 80 g/l or less;

- III degree – hemorrhagic shock – severe weakness, pale, cold skin, thready pulse, SBP 80 mmHg. Anuria.

I degree - blood loss 15-20%, II degree - up to 29%, III degree - 30 percent or more.

The approximate volume of blood loss can be determined by calculating the Algover shock index (the ratio of the pulse rate to the level of systolic blood pressure).

Shock index Volume of blood loss (% of blood volume)

- 0.8 and less than 10

- 0,9-1,2 20

- 1,3-1,4 30

- 1.5 and more 40

Bleeding in the first trimester of pregnancy.

The main causes of bleeding in the first trimester of pregnancy:

- Spontaneous miscarriages

- Bleeding associated with hydatidiform mole

- Cervical pregnancy

- Cervical pathology - cervical canal polyps, decidual polyps, cervical cancer - are less common than the first 3 groups.

Spontaneous miscarriages.

Clinical diagnosis is based on:

- identifying doubtful, probable signs of pregnancy: delayed menstruation, the appearance of whims, engorgement of the mammary glands, the appearance of colostrum. Vaginal examination data: an increase in the size of the uterus, softening in the isthmus area, which makes the uterus more mobile in the isthmus area, asymmetry of the uterus (bulging of one of the corners of the uterus);

- in case of involuntary termination of pregnancy, the two leading symptoms are: pain and symptoms of blood loss. Spontaneous miscarriages are characterized by their stage-by-stage course: threatened miscarriage, incipient miscarriage, ongoing abortion, incomplete and complete spontaneous miscarriage. Differential diagnosis between these conditions is based on the severity of bleeding symptoms and structural changes in the cervix.

Threatened miscarriage: bleeding can be very scanty, pain is either absent or has an aching, dull character in the lower abdomen. During vaginal examination, we find an unchanged cervix.

Incipient miscarriage: bleeding may be slow, pain is cramping in nature, the cervix may be slightly shortened, the external os may be slightly open. A threatened and incipient miscarriage occurs against the background of the woman’s satisfactory condition. No immediate measures are required to stop bleeding. At the hospital stage, the woman needs to create rest, use sedatives, antispasmodics can be administered intramuscularly (gangleron, no-spa, baralgin, magnesium sulfate 10 ml of 25% solution, progesterone). In the hospital, the issue of continuing the pregnancy is decided if the woman is not interested (it is necessary to perform curettage of the uterine cavity).

Abortion in progress: bleeding is profuse, pain is cramping in nature; the general condition changes and depends on the amount of blood loss. During vaginal examination or speculum examination: the cervix is shortened, the cervical canal is passable for one bent finger. Emergency care is required in the form of urgent hospitalization; in the hospital, curettage of the uterine cavity is performed, with compensation for blood loss, depending on its volume and the condition of the woman.

In case of incomplete spontaneous abortion, the bleeding is dark red in color, with clots, and can be significant. All this is accompanied by cramping pain in the lower abdomen. During vaginal examination or speculum examination: placental tissue, parts of the fertilized egg are determined in the cervical canal, the cervix is significantly shortened, the cervical canal freely allows 1.5 - 2 fingers to pass through. Emergency care consists of curettage of the uterine cavity, removal of the remnants of the fertilized egg; compensation for blood loss depending on its volume and the woman’s condition.

With a complete spontaneous miscarriage, there is no bleeding, the fertilized egg is completely released from the uterus. No immediate assistance is required. It is necessary to check the uterine cavity by curettage to make sure that there are no remnants of the fertilized egg.

Bubble drift.

The main characteristic of this pathology is that the chorionic villi turn into grape-shaped formations. And all the villi can turn into vesicles containing a large amount of estrogens, or there may be partial transformation. The risk group for the development of hydatidiform mole includes:

- women who have had a hydatidiform mole,

- women with inflammatory diseases of the genitals,

- women with ovarian hormonal dysfunction.

Clinical diagnosis is based on:

- determining pregnancy based on probable, doubtful and other signs of pregnancy. In contrast to a normal pregnancy, the symptoms of early toxicosis are much more pronounced, most often moderate or severe vomiting;

- with hydatidiform mole, symptoms of late toxicosis appear very early: edema syndrome, proteinuria. Hypertension also appears, but only later. The diagnosis of hydatidiform mole is made on the basis of a discrepancy between the size of the uterus and the period of delayed menstruation, which can be determined by vaginal examination and ultrasound. The most important criterion for diagnosing hydatidiform mole is the titer of human chorionic gonadotropin, which increases by more than a thousand times compared to a normal pregnancy.

Bleeding can be stopped in only one way - curettage of the uterine cavity. A characteristic feature of this curettage is that it must be carried out under the intravenous administration of uterotonics and it is necessary to remove as much of the altered tissue as possible with an abortion tool. Uterotonics are administered to cause the uterus to contract so that the surgeon can better navigate the uterine cavity. You must be careful, since a hydatidiform mole can be destructive, that is, penetrating into the muscular wall of the uterus, right down to the serous membrane. If the uterus is perforated during curettage, it is necessary to amputate the uterus.

Cervical pregnancy.

It is almost never full term. Pregnancy is most often terminated before 12 weeks. Risk groups for developing cervical pregnancy include:

- women with a burdened obstetric history,

- survivors of inflammatory diseases, cervical diseases, menstrual irregularities such as hypomenstrual syndrome.

What matters is the high mobility of the fertilized egg not in the body of the uterus, but in the lower segment or in the cervical canal.

The diagnosis can be made during a special gynecological or obstetric examination: when examining the cervix in the speculum, the cervix looks barrel-shaped, with a displaced external pharynx, with pronounced cyanosis, and bleeds easily during examination. The body of the uterus has a denser consistency and is smaller than the expected gestational age. Bleeding during cervical pregnancy is always very profuse, because the structure of the choroid plexuses of the uterus is disrupted - the lower branch of the uterine artery, the pudendal artery, comes here. Since the thickness of the cervix is significantly less than the thickness of the uterus in the body area, the integrity of the blood vessels is compromised and bleeding cannot be stopped without surgical intervention. It is a mistake to begin providing assistance with curettage of the uterine cavity, and since the severity of barrel-shaped, cyanotic changes in the cervix depends on the stage of pregnancy, the bleeding intensifies. As soon as a diagnosis of cervical pregnancy is established, which can be confirmed by ultrasound data, curettage of the uterine cavity cannot be performed, but this bleeding must be stopped by removing the uterus without appendages. There is no other option for stopping bleeding during cervical pregnancy and there should not be, since the bleeding comes from the lower branches of the uterine artery.

Polyps of the cervical canal.

Rarely cause significant bleeding; more often it is minor bleeding. Decidual polyp is a growth of decidual tissue, and its excess descends into the cervical canal. Such a polyp most often disappears on its own, or it can be removed by carefully unscrewing it. A bleeding polyp should be removed, but without curettage of the uterine cavity, with hemostatic therapy and pregnancy-preserving therapy.

Cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer in a pregnant woman is extremely rare, since most often this pathology develops in women over 40 years of age, in women with a history of many births and abortions, and in women who frequently change sexual partners. Cervical cancer, as a rule, is diagnosed during mandatory examination of the cervix during pregnancy 2 times - when the pregnant woman is registered and when maternity leave is issued. Cervical cancer appears as exophytic (cauliflower-type) and endophytic growths (barrel-shaped cervix). Most often, this woman had underlying cervical diseases. In case of cervical cancer, depending on the stage of pregnancy, surgical delivery is carried out, followed by hysterectomy - for long periods, removal of the uterus for short periods of pregnancy with the consent of the woman. No conservative methods of stopping bleeding for cervical cancer are used!

Obstetric hemorrhage includes bleeding associated with ectopic pregnancy. If previously a woman died from bleeding during an ectopic pregnancy, then her death was considered as a gynecological pathology, but now it is considered as an obstetric pathology. As a result of the localization of pregnancy in the isthmic tubal angle of the uterus, there may be uterine rupture in the interstitial region, and a clinical picture of ectopic pregnancy may occur.

Bleeding in the second half of pregnancy.

The main causes of obstetric bleeding in the second half of pregnancy:

- Placenta previa

- Premature abruption of the normally located placenta (PONRP)

- Uterine rupture.

Currently, after the advent of ultrasound, the diagnosis of placenta previa began to be made before the onset of bleeding, and the main group of maternal mortality are women with PONRP.

Placenta previa and PONRP.

Placenta previa accounts for 0.4-0.6% of the total number of births. There are complete and incomplete placenta previa. The risk group for the development of placenta previa are women with a history of inflammatory, degenerative diseases, genital hypoplasia, uterine malformations, and isthmicocervical insufficiency.

Normally, the placenta should be located in the area of the fundus or body of the uterus, along the back wall, with a transition to the side walls. The placenta is located much less frequently along the anterior wall, and this is protected by nature, because the anterior wall of the uterus undergoes much greater changes than the posterior one. In addition, the location of the placenta along the posterior wall protects it from accidental injury.

In PONRP, bleeding can be stopped only by cesarean section, regardless of the condition of the fetus + retroplacental hematoma of at least 500 ml. a mild degree of detachment may practically not manifest itself.

Table. Tactics for managing pregnant and parturient women with placenta previa

| bleeding | gestational age | doctor's tactics |

| Abundant with complete placenta previa | regardless of gestational age | caesarean section, replacement of blood loss |

| Small with complete placenta previa | less than 36 weeks | observation, tocolytics, corticosteroids. · Magnesia, no-spa, gangleron, dibazol, papaverine, beta-adrenergic agonists are not allowed, as they have a peripheral vasodilating effect and will increase bleeding. · Combating anemia, with hemoglobin 80 g/l and below - blood transfusion. · Prevention of fetal distress syndrome (with a caesarean section, the child will die not from anemia, which should not exist, but from hyaline membrane disease). Glucocorticosteroids are used - prednisolone, dexamethasone (2-3 mg per day, maintenance dose 1 mg/day). |

| Bleeding with incomplete placenta previa | regardless of the deadline | opening of the membranes. If the bleeding has stopped, then childbirth is carried out through the natural birth canal; If bleeding continues, a cesarean section is performed. |

Uterine rupture.

In the second half of pregnancy, the causes of obstetric bleeding, in addition to the above reasons, may include uterine rupture as a result of the presence of a scar on the uterus after a conservative myomectomy, cesarean section, or as a result of destructive hydatidiform mole and chorionepithelioma. Symptoms: presence of internal or external bleeding.

If uterine rupture occurs in the second half of pregnancy, then very often this situation ends in death, since no one expects this condition. Symptoms: constant or cramping pain, bright spotting, against the background of which the general condition changes with a characteristic clinical picture of hemorrhagic shock. Emergency care is needed - laparotomy, amputation of the uterus or suturing of a uterine rupture if the localization allows this, replenishment of blood loss.

Table. Differential diagnosis between placenta previa, PONRP and uterine rupture

| Symptoms | Placenta previa | PONRP | Uterine rupture |

| Essence | Placenta previa is the location of chorionic villi in the lower segment of the uterus. Complete presentation - complete covering of the internal os, incomplete presentation - incomplete coverage of the internal os (with vaginal examination, the membranes of the ovum can be reached). | ||

| Risk group | Women with a burdened obstetric and gynecological history (inflammatory diseases, curettage, etc.). | Women with pure gestosis (occurred against a somatically healthy background) and combined gestosis (against the background of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, etc.). The basis of gestosis is vascular pathology. Since gestosis occurs against the background of multiple organ failure, the symptom of bleeding is more severe | Women with a burdened obstetric and gynecological history, with scars on the uterus - after surgical interventions on the uterus, with an overstretched uterus, polyhydramnios, multiple pregnancies |

| Bleeding symptom | With complete placenta previa, it is always external, not accompanied by pain, scarlet blood, the degree of anemia corresponds to external blood loss; This is recurring bleeding that begins in the second half of pregnancy. | It always begins with internal bleeding, less often combined with external bleeding. In 25% of cases there is no external bleeding at all. Bleeding with dark blood, with clots. Develops against the background of multiple organ failure. The degree of anemia does not correspond to the amount of external blood loss. The woman's condition is not adequate to the volume of external bleeding. Bleeding develops against the background of the chronic stage of DIC syndrome. With detachment, an acute form of DIC syndrome begins. | Combined bleeding - external and internal, scarlet blood, accompanied by the development of hemorrhagic and traumatic shock. |

| Other symptoms | The increase in blood volume is often small, women are low weight and suffer from hypotension. If gestosis develops, it is usually with proteinuria, not hypertension. Against the background of placenta previa, with repeated bleeding, the clotting potential of the blood decreases. | ||

| Pain syndrome | Absent | Always pronounced, pain is localized in the abdomen (the placenta is located on the anterior wall), in the lumbar region (if the placenta is located on the posterior wall). The pain syndrome is more pronounced in the absence of external bleeding, and less pronounced in the presence of external bleeding. This is explained by the fact that a retroplacental hematoma that does not find a way out causes greater pain. The pain syndrome is more pronounced when the hematoma is located in the bottom or body of the uterus, and much less if there is an abruption of the low-lying placenta, with easier access of blood from the hematoma. | It can be expressed slightly, for example, during childbirth, if the uterus begins to rupture along the scar, that is, with histopathic conditions of the myometrium. |

| Uterine tone | The tone of the uterus is not changed | Always elevated, the uterus is painful on palpation, you can palpate a bulge on the anterior wall of the uterus (the placenta is located along the anterior wall). | The uterus is dense, well contracted, parts of the fetus can be palpated in the abdominal cavity. |

| Fetal condition | Suffering secondarily when the mother’s condition worsens, in accordance with blood loss. | Suffering up to death when more than 1/3 of the placenta is detached. There may be antenatal fetal death. | Fetus |

Emergency care for bleeding includes:

- Stop bleeding

- Timely replacement of blood loss

Treatment is complicated by the fact that with PONRP, against the background of gestosis, there is a chronic DIC syndrome; with placenta previa, placenta accreta may occur, given the small thickness of the muscle layer in the lower segment and the dystrophic changes that develop there.

Bleeding in the first stage of labor.

Causes of bleeding in the 1st stage of labor:

- Cervical rupture

- PONRP

- Uterine rupture

- Cervical rupture.

There is rarely heavy bleeding from a cervical rupture, but there can be heavy bleeding if the rupture reaches the vaginal vault or extends to the lower segment of the uterus.

Risk group:

- women entering labor with an immature birth canal (rigid cervix),

- women with discoordinated labor,

- women with large fetuses,

- with excessive use of uterotonics, with insufficient administration of antispasmodics.

Cervical rupture is manifested clinically by bright scarlet bleeding of varying intensity. The rupture most often begins after the opening of the uterine pharynx by 5-6 cm, that is, when the head begins to move along the birth canal. Cervical rupture occurs in women with rapid labor. A cervical rupture may not be diagnosed, that is, be asymptomatic, due to the tamponing effect of the advancing head. As a rule, cervical rupture does not occur with breech presentation and with weak labor. The final diagnosis is established by examining the soft birth canal in the postpartum period. A feature of suturing a 3rd degree uterine rupture is the finger control of the suture on the upper corner of the wound, in order to make sure that the cervical rupture does not spread to the area of the lower segment.

Prevention of cervical rupture: preparation of the cervix during pregnancy, administration of antispasmodics in the first stage of labor (intramuscular, intravenous, long-term epidural anesthesia has the best effect.

PONRP.

PONRP in the first stage of labor is manifested by the appearance of pain in the uterine area that does not coincide with contractions, tension of the uterus between contractions, that is, the uterus does not relax or relaxes poorly, and the appearance of bloody clots. During childbirth, PONRP can develop as a result of excessive labor stimulation, when the administration of uterotonics is not regulated, and especially in women in labor with the presence of gestosis, discoordinated labor, hypertension, that is, when there is some prerequisite for vascular pathology. As soon as the diagnosis is made in the first stage of labor, bleeding is stopped by cesarean section. Very rarely, treatment is carried out conservatively, only if there are no symptoms of increasing fetal hypoxia; in multiparous women with full dilatation of the uterine pharynx - in such women, rapid delivery is possible.

Uterine rupture.

It is characterized by inappropriate behavior of a woman against the background of contractions. The doctor assesses the contractions as insufficient in strength, and the woman is worried about strong contractions and persistent pain. Bloody discharge from the vagina appears. Symptoms of intrauterine fetal hypoxia may develop. If symptoms of uterine scar failure appear, childbirth should be completed by cesarean section.

Bleeding in the second stage of labor.

The main causes of bleeding in the second stage of labor:

- Uterine rupture

- PONRP

If there is a uterine rupture , then the woman’s serious condition, associated with traumatic and hemorrhagic shock, develops very quickly, intrapartum fetal death occurs, and then the diagnosis is clear. But there may be erased symptoms.

to diagnose PONRP , because contractions are accompanied by pushing, the tone of the uterus is significantly increased, and most often the diagnosis is made after the birth of the fetus, based on the release of dark bloody clots after the fetus. If there is a uterine rupture in the second period and the head is on the pelvic floor, then it is necessary to apply obstetric forceps or remove the fetus by the pelvic end. With PONRP - shortening the period of expulsion by perineotomy or application of obstetric forceps.

Bleeding in the third stage of labor.

The causes of bleeding in the third stage of labor are associated with impaired separation and discharge of the placenta:

- Tight attachment

- True accretion (only with partial true accretion or partial tight attachment bleeding is possible)

- Infringement of the placenta in the area of the internal pharynx (spasm of the pharynx)

- Remains of placental tissue in the uterus

Bleeding may be very heavy.

Emergency care for bleeding in the afterbirth period consists of an immediate operation of manual separation of the placenta and release of the placenta against the background of intravenous anesthesia and the mandatory administration of uterotonics, with a mandatory assessment of the general condition of the woman in labor and the amount of blood loss with mandatory compensation. It is necessary to start this operation if there is a blood loss of 250 ml and ongoing bleeding; you should never expect a pathological amount of blood loss (more than 400 ml). Each manual entry into the uterine cavity equals in itself a loss of 1 liter of bcc.

Bleeding in the early postpartum period.

The main causes of bleeding in the early postpartum period coincide with risk factors:

- Women with a burdened obstetric and gynecological history

- Pregnancy complicated by gestosis

- Childbirth with a large fetus

- Polyhydramnios

- Multiple pregnancy

Variants of hypotonic bleeding.

- Bleeding immediately and profusely. In a few minutes you can lose 1 liter of blood.

- After taking measures to increase the contractility of the uterus: the uterus contracts, bleeding stops after a few minutes - a small portion of blood - the uterus contracts, etc. and so gradually, in small portions, blood loss increases and hemorrhagic shock occurs. With this option, the vigilance of personnel is reduced and it is the lack of attention that often leads to death since there is no timely compensation for blood loss.

The main operation that is performed for bleeding in the early postpartum period is called manual examination of the uterine cavity (MCE).

Objectives of the ROPM operation:

- determine whether there are any retained parts of the placenta left in the uterine cavity and remove them;

- determine the contractile potential of the uterus;

- determine the integrity of the uterine walls - whether there is a uterine rupture (clinically it is sometimes difficult to make a diagnosis);

- determine whether there is a malformation of the uterus or a tumor of the uterus (a fibromatous node is often the cause of bleeding).

Sequence of performing the ROPM operation.

- Determine the amount of blood loss and the general condition of the woman.

- Treat hands and external genitalia.

- Give intravenous anesthesia and begin (continue) the administration of uterotonics.

- Insert your hand into the vagina and then into the uterine cavity.

- Empty the uterine cavity of blood clots and retained parts of the placenta (if any).

- Determine the tone of the uterus and the integrity of the uterine walls.

- Inspect the soft birth canal and suture any damage, if any.

- Re-evaluate the woman’s condition and blood loss, compensate for blood loss.

Sequence of actions to stop hypotonic bleeding.

- Assess the general condition and volume of blood loss.

- Intravenous anesthesia, start (continue) administration of uterotonics.

- Proceed with manual examination of the uterine cavity.

- Remove clots and retained parts of the placenta.

- Determine the integrity of the uterus and its tone.

- Inspect the soft birth canal and suture the damage.

- Against the background of ongoing intravenous administration of oxytocin, simultaneously inject 1 ml of methylergometrine intravenously and 1 ml of oxytocin can be injected into the cervix.

- Insertion of tampons with ether into the posterior fornix.

- Re-assessment of blood loss and general condition.

- Reimbursement for blood loss.

Atonic bleeding.

Obstetricians also distinguish atonic bleeding (bleeding in the complete absence of contractility - Couveler's uterus). They differ from hypotonic bleeding in that the uterus is completely inactive and does not respond to the administration of uterotonics.

If hypotonic bleeding does not stop with ROPM, then further tactics are as follows:

- apply a suture to the posterior lip of the cervix with a thick catgut ligature - according to Lositskaya. Mechanism of hemostasis: reflex contraction of the uterus, since a huge number of interoreceptors are located in this lip;

- the same mechanism when introducing a tampon with ether;

- applying clamps to the cervix. Two fenestrated clamps are inserted into the vagina, one open branch is located in the uterine cavity, and the other in the lateral vaginal fornix. The uterine artery departs from the iliac artery in the area of the internal os and is divided into descending and ascending parts. These clamps compress the uterine artery.

These methods sometimes help stop bleeding, and sometimes are steps in preparation for surgery (as they reduce bleeding).

Massive blood loss is considered to be blood loss during childbirth of 1200-1500 ml. Such blood loss dictates the need for surgical treatment - removal of the uterus.

Having started the operation to remove the uterus, you can try one more of the reflex methods of stopping bleeding:

- ligation of vessels according to Tsitsishvili. Vessels passing through the round ligaments, the ligament proper of the ovary, the uterine tube, and the uterine arteries are ligated. The uterine artery runs along the rib of the uterus. If it does not help, then these clamps and vessels will be prepared for removal surgery;

- electrical stimulation of the uterus (now they are moving away from it). Electrodes are placed on the abdominal wall or directly on the uterus and a shock is delivered;

- acupuncture.

Along with stopping bleeding, blood loss is compensated.

Main data sources.

A.P. Kolesnichenko, G.V. Gritsan. Features of etiopathogenesis, diagnosis and intensive therapy of DIC syndrome in critical conditions in an obstetrics and gynecology clinic. Guidelines. Krasnoyarsk - 2001

Premature placental abruption

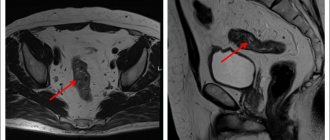

Premature placental abruption (PAP) is the premature separation of a normally implanted placenta from the uterine wall, causing bleeding between the uterine wall and the placenta. About 50% of cases of premature abruption of a normally located placenta occur before 30 weeks of gestation, 15% during childbirth, and 30% are diagnosed only after birth when examining the surface of the placenta. Detachment of a significant surface of the placenta can lead to premature labor, uterine tetany, the development of disseminated intravascular coagulation and hypovolemic shock.

The primary cause of placental abruption is unknown, although the condition is associated with numerous risk factors and precipitating factors. These factors include maternal hypertension, previous placental abruption, maternal cocaine use, external trauma, and rapid decompression of an overdistended uterus.

At the beginning of placental abruption, blood does not clot and flows out of the placental abruption site. The growing amount of blood can cause further separation of more of the placenta. In 20% of cases of premature placental abruption, bleeding is limited to the uterine cavity (hidden, internal). In the remaining 80% of cases of placental abruption, blood leaks into the cervix and open, or external, bleeding occurs. Due to the possible leakage of blood during open bleeding, the presence of a large retroplacental hematoma, which can lead to fetal death, is less likely.

Bleeding from placental abruption leads to maternal anemia; more severe cases may be complicated by hypovolemic shock, acute renal failure and maternal death. Fetal death occurs in 35% of cases with clinically diagnosed premature placental abruption and in 50-60% of cases with severe forms. The cause of fetal death is acute hypoxia due to a decrease in the surface area of the placenta and maternal bleeding.

Epidemiology

Placental abruption occurs in 0.5-1.5% of all pregnancies and accounts for 30% of cases of bleeding in the third trimester and 15% of cases of perinatal mortality. The most common risk factors for premature placental abruption are maternal hypertensive diseases (chronic hypertension or preeclampsia).

Severe cases of placental abruption, accompanied by fetal death, are associated with maternal hypertension in 50% of cases: 25% with chronic hypertension and 25% with preeclampsia. The risk of recurrent PVP is 10%, after two cases of premature placental abruption in the anamnesis, this risk increases to 25% of cases.

Clinic

The classic symptoms of premature placental abruption are vaginal bleeding in the third trimester of pregnancy, which is accompanied by abdominal pain or tenderness of the uterus on palpation and frequent, strong contractions of the uterus. But about 30% of cases of premature placental abruption (when a small part of the placenta is detached) are asymptomatic or have mild clinical symptoms and are diagnosed only when examining the placenta after birth.

Objective examination . When examining patients with premature placental abruption, vaginal bleeding and a hard, painful uterus are usually found. Tocometry reveals both frequent short uterine contractions and tetanic contractions.

When monitoring fetal heart rate, adverse changes are observed that are a consequence of hypoxia. The classic symptom of placental abruption, which occurs during cesarean section, is the penetration (extravasation) of the myometrium with blood, which can reach the serous lining of the uterus - Couveler's uterus. The amount of blood in Kuveler's uterus does not usually interfere with postpartum uterine contractions or increase the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. In the United States, in the absence of other complications (for example, coagulation disorders), Couveler's uterus is not an indication for hysterectomy.

Diagnostics

The diagnosis of premature placental abruption is based primarily on clinical data. Only 2% of cases of PVP are diagnosed by ultrasound (visualization of retroplacental hematoma). But, given that PVP may have clinical symptoms similar to those of placenta previa, ultrasound examination is performed to exclude the diagnosis of PVP. The presence of premature placental abruption is confirmed by examining the surface of the placenta after delivery. The presence of a retroplacental clot (hematoma) with destruction of the subordinate area of the placenta confirms the diagnosis.

Treatment

Given the possibility of rapid development of catastrophic complications with PVP (massive bleeding, disseminated intravascular coagulation, fetal hypoxia), urgent delivery is usually performed by cesarean section. But in some cases, placental abruption is minor, does not lead to serious complications and does not require immediate delivery.

The doctor’s algorithm for suspected premature placental abruption includes the following points:

1. Stabilization of the patient’s vital functions. Urgent hospitalization, catheterization of central or peripheral veins, implementation of fetal heart rate monitoring. Laboratory examination: general blood test - blood group and Rh factor, coagulogram (prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, level of fibrinogen and fibrinogen degradation products. Rh-negative patients are prescribed anti-Rhesus immunoglobulin to prevent alloimmunization.

2. Preparing for possible massive bleeding. Implementation of standard anti-shock measures (vein catheterization, infusion of solutions, collection of blood, plasma, compatibility tests. Total blood loss with premature placental abruption is usually more expected (“hidden” bleeding).

3. Preparation for premature birth. To accelerate the maturation of the fetal lungs, dexamethasone (betamethasone) is prescribed; If the patient’s condition is stable and the fetus is immature, tocolysis can be performed to continue pregnancy up to 34 weeks.

4. Delivery in case of increased bleeding or fetal hypoxia. Urgent delivery by cesarean section is performed in patients with a threat of massive bleeding, unstable condition, or when initial signs of coagulopathy appear. With minor controlled bleeding, absence of fetal hypoxia, coagulation disorders and expectation of an early birth, vaginal delivery from a previous amniotomy is possible.

It is believed that amniotomy helps reduce extravasation of blood into the myometrium and limits the entry of thromboplastic substances into the maternal circulation. In case of fetal hypoxia, the method of choice will be cesarean section.

Obstetric hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide , killing 127,000 women each year, accounting for 25% of all maternal deaths. In the Russian Federation, maternal mortality from obstetric hemorrhage in the structure of its causes is 14-17%, consistently occupying 2nd place after mortality associated with abortion. Relative to the total number of births, the frequency of obstetric hemorrhage ranges from 2.7 to 8% , with 2-4% associated with uterine hypotension. On average, 1 woman per day in Russia dies from causes related to pregnancy and childbirth, and every seventh of them is from bleeding. The use of Zhukovsky's balloon tamponade is possible not only when bleeding has already begun, but also as a preventive measure.

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is considered the most dangerous postpartum complication for the mother . It is well known that if proper medical care is not provided, PPH has the shortest time to death among all obstetric emergencies - only 2 hours; this means that late identification of the disease and lack of appropriate treatment for PPH are critical factors that can lead to poor outcome.

PPH is not an independent diagnosis, but only a symptom of many disorders of postpartum hemostasis, when, when observing vaginal bleeding, obstetricians cannot immediately determine the cause of the complication. Once the treating physician recognizes this acute and uncertain condition requiring urgent action, the only sure-fire, tried-and-true course of action is to aggressively and promptly implement a sequence of procedures aimed at treating PPH.

Selecting the best and most effective treatment tools and techniques is undoubtedly of paramount importance. The sequence of measures for uterine bleeding in the early postpartum period

. Review of standards for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage Materials prepared by Zhukovsky Ya. G.

Main reasons

Bleeding that occurs in the first 2 hours of the postpartum period is called early postpartum hemorrhage. Its causes are, most often, retention of parts of the placenta in the uterine cavity, hypotension or atony of the uterus, a violation of the blood coagulation system, and uterine rupture. When parts of the placenta are retained in the uterine cavity, the postpartum uterus becomes large and blood clots are released from the genital tract. Diagnosis is based on a thorough examination of the placenta and membranes after the birth of the placenta. If there is a defect in the placenta or there is doubt about its integrity, manual examination of the postpartum uterus and removal of placental remnants is indicated. The most common cause of early postpartum hemorrhage is a violation of the contractility of the myometrium - hypotension and atony of the uterus. Hypotony of the uterus is a decrease in its tone and insufficient contractility. Uterine atony is a condition in which the uterus completely loses the ability to contract and does not respond to medications and other types of stimulation. The causes of hypo- and atonic bleeding are disturbances in the functional state of the myometrium at the onset of labor due to gestosis, diseases of the cardiovascular system, kidneys, liver, central nervous system, endocrinopathies, scar changes in the myometrium, uterine tumors, hyperextension of the uterus due to multiple pregnancy, polyhydramnios, large fetus. The functional state of the myometrium may be impaired during prolonged labor, the use of drugs that reduce uterine tone, or prolonged use of contractile drugs. Anomalies of placenta attachment, retention of the placenta and its parts in the uterine cavity, and premature detachment of a normally located placenta are also important.

Clinic of hypotonic and atonic bleeding

Clinically, there are 2 types of early postpartum hemorrhage:

- the bleeding immediately takes on a massive, profuse character. The uterus is atonic, flabby, does not respond to external massage, manual examination of the uterine cavity, or to the introduction of contractile agents. Hypovolemia, hemorrhagic shock, and disseminated intravascular coagulation syndrome quickly develop;

- bleeding is wavy. The uterus periodically relaxes and releases blood in portions of 150-300 ml. In response to the introduction of contractile agents, external massage of the uterus, myometrial contractility and tone are temporarily restored, and bleeding stops. Due to the fragmentation of blood loss, a woman’s condition may be compensated for a certain period of time.

If assistance is provided on time and in sufficient volume, the tone of the uterus is restored and bleeding stops. If timely assistance is not provided, the body's compensatory capabilities are depleted, bleeding intensifies, hemostasis disorders occur, and hemorrhagic shock and disseminated intravascular coagulation develop.

Treatment of hypotonic and atonic bleeding

Methods of combating hypotonic and atonic bleeding in the early postpartum period are divided into medicinal, mechanical and surgical. After emptying the bladder, apply a cold pack on the stomach and begin external massage of the uterus through the anterior abdominal wall. At the same time, 5 units (1 ml) of oxytocin and 1 ml of a 0.02% solution of methylergometrine in 20 ml of a 40% glucose solution are administered intravenously. If this does not lead to a lasting effect, they immediately begin manual examination of the walls of the postpartum uterus under intravenous anesthesia. At the same time, they are convinced that there are no parts of the placenta in the uterus, and a violation of the integrity of the uterus is excluded; have a powerful reflex effect on myometrial contractility with two-handed massage. The operation is highly effective in the early stages of bleeding. A good hemostatic effect is achieved by introducing prostaglandins into the cervix. You should pay attention to the tablet drug containing prostaglandins - misoprostol. All measures to stop bleeding are carried out in parallel with adequate infusion and transfusion therapy. If there is no effect from manual examination of the uterus, this most often indicates a coagulopathic nature of the bleeding. It must be remembered that it is unacceptable to re-use manipulations that were ineffective the first time they were performed. The lack of effect of timely conservative therapy and ongoing bleeding are indications for laparotomy and the use of surgical methods to stop bleeding. The effectiveness of “intermediate” measures between the conservative and surgical stages, including the introduction of an intrauterine balloon or compression of the abdominal aorta, cannot be underestimated. Tamponade of the uterine cavity, described by a group of foreign authors, allows in some cases to avoid surgical treatment. In our country, the method of balloon tamponade of the uterus using the Optimiss intrauterine catheter has become widespread. According to V.E. Radzinsky et al. (2008), in case of massive obstetric bleeding, tamponade with an intrauterine balloon as a way to stop it is effective in 90% of cases. Therefore, the use of an intrauterine balloon as a method of stopping bleeding or as a temporary measure that reduces the rate of blood loss and gives time to prepare for surgical intervention, according to leading domestic obstetricians, should be considered mandatory. The surgical stage also has a clear algorithm of actions. When the uterus is exposed, prostaglandins are injected into the muscle. If the volume of blood loss is more than 1500 ml, ligation of the internal iliac arteries is indicated first. If blood loss is 1000-1500 ml or in the absence of conditions for ligation of the iliac arteries, it is necessary to ligate the uterine vessels, followed by the application of hemostatic compression sutures. The literature describes a technique for the simultaneous use of compression hemostatic sutures on the uterus and an intrauterine hemostatic balloon. If the lower segment is overstretched, tightening sutures are applied. If bleeding continues, hysterectomy is performed. If possible, instead of ligating the vessels and removing the uterus, embolization of the uterine vessels is performed

Late postpartum bleeding

Late postpartum hemorrhage occurs 2 hours or more after the end of labor. Their causes may be uterine hypotension, retention of parts of the placenta in the uterine cavity, disorders in the blood coagulation system, trauma to the birth canal, and diseases of the blood system. Hypotonic bleeding occurs on the first day after birth. The pathogenesis and clinical picture are similar to those of early postpartum hypotonic bleeding. When part of the placenta is retained in the uterine cavity, the size of the uterus is increased, its consistency is soft, and the cervical canal is passable for 1-2 fingers. A manual examination of the uterine cavity is carried out and parts of the placenta are removed, hemostatic and antibacterial therapy is carried out, and uterine contractions are prescribed. Bleeding in the late postpartum period can be caused by injuries to the birth canal due to improper suturing technique. In this case, hematomas of the vagina or perineum are formed. In this case, it is necessary to remove all previously applied sutures, ligate the bleeding vessel, and connect the edges of the wound. These manipulations are performed under general anesthesia.

Hemorrhagic shock

A severe maternal complication of massive bleeding is hemorrhagic (hypovolemic) shock. With blood loss of more than 25% of the circulating blood volume (CBV), or more than 1500 ml, the clinical picture of hemorrhagic shock develops. In 10% of cases of PVP that resulted in fetal death, that is, with abruption of > 2/3 of the placenta, the development of disseminated intravascular coagulation, or disseminated intravascular coagulation syndrome (DIC) is possible.

This syndrome develops as a result of the entry of massive doses of tissue thromboplastin (from places of damage to the placenta) into the maternal vascular system, which promotes the activation of the coagulation cascade, primarily in the microvascular bed. This leads to the development of ischemic necrosis of parenchymal organs - kidneys, liver, adrenal glands, pituitary gland.

Ischemic renal necrosis can develop as a result of acute tubular necrosis or bilateral cortical necrosis and manifests with oliguria and anuria. Bilateral cortical necrosis is a fatal complication that requires hemodialysis and can lead to death of the woman due to uremia in 1-2 weeks.

Management of patients with hypovolemic shock requires rapid restoration of lost blood volume. Central venous catheterization is performed, central venous pressure is measured to monitor the restoration of blood loss, a catheter is inserted into the bladder to monitor diuresis, oxygen inhalation is introduced, and infusion of blood and blood substitutes is started until the NET level is more than 30% and urine output is > 0.5 ml/kg / hour Studies of platelet counts, fibrinogen levels and serum potassium are performed after infusion of every 4-6 vials of blood.

Blood coagulation tests (tests for DIC) are carried out every 4 hours before delivery. The most sensitive clinical test for the development of DIC syndrome is the level of fibrinogen degradation products (FDP), although only a single study of the FDP level has prognostic significance, i.e. Based on the level of PDF, one cannot draw a conclusion about the effectiveness of treatment. Although normal PDP results do not exclude the possibility of DIC, fibrinogen levels and platelet counts are the most important markers of DIC.

Urgent delivery is the main component of the treatment of DIC syndrome, and leads to regression of its manifestations. The method of choice is caesarean section. If the fetus dies and the patient's condition is stable, vaginal delivery is possible. If the platelet count is <50,000 or the fibrinogen level is <1 g/L, these blood components must be restored. Restoration of fibrinogen levels is achieved by transfusion of fresh frozen plasma or cryoprecipitate. Heparin is not usually used.

Late postpartum hemorrhage: relevance of the problem and ways to solve it

- Belousova Alexandra Andreevna

- Aryutin Dmitry Gennadievich

- Toniyan Konstantin Alexandrovich

- Dobrovolskaya Daria Alekseevna

- Dukhin Armen Olegovich

Summary The objectives

of the study are to improve the treatment outcomes of patients diagnosed with late postpartum hemorrhage and to develop an algorithm for their management.

Material and methods.

In the course of a retro- and prospective study, an analysis was made of the treatment of 75 patients with bleeding in the late postpartum period, who, depending on the severity of the condition and the results of the examination, underwent conservative or surgical treatment.

results

. Comprehensive, well-chosen conservative therapy, taking into account the volume of blood loss and its replacement, in some cases allows one to avoid surgical intervention. If instrumental emptying of the uterine cavity is ineffective, repeated surgical treatment is inappropriate; the method of choice should be endovascular occlusion of the uterine and internal iliac vessels, which is a highly effective, relapse-free method of stopping bleeding.

conclusions

. The problem of late postpartum complications remains extremely relevant to this day. The development of modern treatment algorithms based on knowledge of pathogenesis and the use of the latest pharmacological and surgical technologies is promising.

Key words: maternal mortality, complications of the postpartum period, late postpartum hemorrhage, endometritis, hemetometra, coagulopathy, uterine artery embolization

Obstetrics and gin.: news, opinions, training. 2021. T. 6, no. 3. pp. 119-126. doi: 10.24411/2303-9698-2018-13014

In recent years, Russia has seen a decline in maternal mortality rates. Worldwide, its level has decreased by 44% over the past 25 years. In Russia, the maternal mortality rate for 2015 was almost equal to the world level and amounted to 10.7 per 100 thousand live births (according to Rosstat, the number of maternal deaths in 2015 was 217, according to the Ministry of Health - 207). Today, bleeding remains one of the most common causes of death in women in labor and postpartum [2-4, 6] - they are in 2nd place, second only to extragenital pathology. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2015, more than 30 thousand women died from obstetric hemorrhage worldwide, which is undoubtedly a tragedy of modern obstetrics.

In the Russian Federation, bleeding also ranks second in the structure of maternal mortality after extragenital diseases (according to the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation for 2013) - in 2021 it amounted to 14.2% [3, 4]. One of the factors in reducing this indicator was the implementation of the approved protocol and order of the Russian Ministry of Health No. 572n dated November 1, 2012.

Along with a decrease in mortality, the risk of an increase in the number of diseases in the postpartum period increases; While the algorithm for reducing the incidence of inflammatory complications and bleeding during childbirth and the early postpartum period is well covered in the domestic and foreign scientific literature, the problem of late postpartum complications remains poorly understood and is still controversial [1, 9, 14, 15]. The main reasons for the development of bleeding in the late postpartum period are the retention of parts of the placenta in the uterine cavity and the hematometer. Both conditions lead to impaired contractility of the uterus with the development of its subinvolution, inflammatory reaction of the endometrium and, as a result, uterine bleeding against the background of a progressive clinical picture of postpartum endometritis. Such patients require emergency hospitalization in a hospital for complex therapy with possible instrumental evacuation of the uterine cavity and subsequent prevention of the transition of the inflammatory process to the chronic stage. The management of such patients is significantly complicated by the increase in antibiotic resistance of microorganisms, the increase in the number of erased forms of the disease, the inadequacy of antibiotic therapy and late seeking medical help [2, 5, 7, 8].

A number of authors consider postpartum hemorrhage as a consequence of coagulopathy, anemia, thrombocytopenia developing due to blood loss, predisposing factors for the development and progression of this complication and, depending on the volume of blood lost, they propose different algorithms for the management of such patients [12, 13]. For example, recently there are increasingly more works devoted to minimally invasive methods of treating postpartum hemorrhage - endovascular occlusion of the uterine arteries - with convincingly high positive results in the effectiveness of stopping bleeding without traditional surgical intervention [16, 17].

Thus, interest in the problem of late postpartum complications and its relevance are associated not so much with the increasing number of births, but with the fact that at present there is no unified treatment and diagnostic algorithm for the prevention, identification and management of this group of patients, systematized routing of patients with late postpartum hemorrhage , connecting the maternity hospital, outpatient clinic and gynecological departments of multidisciplinary hospitals into a single network. And the understandable trepidation of obstetricians and gynecologists before those very 42 days increases the already significant proportion of complications and unjustified obstetric aggression towards this group of patients [11].

The objectives of the study are to improve the treatment outcomes of patients diagnosed with late postpartum hemorrhage and to develop an algorithm for their management.

Material and methods

The study was carried out on the basis of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology with a course of perinatology of the Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education "Peoples' Friendship University of Russia" and the Department of Gynecology and Reproductive Surgery of the State Budgetary Institution "City Clinical Hospital No. 29 named after. N.E. Bauman" of the Moscow Department of Health. We conducted a retro- and prospective analysis of the management and treatment of 75 patients with complications of the late postpartum period from 2021 to 2021.

results

The age of the patients ranged from 19 to 40 years, with an average of 28.6±5.06 years.

Among those examined, there were 49 (64.5%) women who gave birth for the first time (group 1), and 26 (35.5%) gave birth again (group 2).

Obstetric history showed that 14 (18.6%) patients had operative delivery, the remaining 82.4% had spontaneous vaginal birth. The groups were compared according to the method of delivery, and in both the 1st and 2nd groups the proportion of spontaneous births prevailed over operative ones (Fig. 1).

In 1 patient from group 1, the placenta was complicated by a tight placenta, which required manual separation of the placenta and removal of the placenta; in 3 patients bleeding occurred in the early postpartum period. In group 2, intrauterine intervention was performed in 3 patients, and 1 patient experienced bleeding in the early postpartum period.

Thus, the total number of intrauterine interventions in the early postpartum period was 4 (6.5%).

In the late postpartum period in obstetric hospitals, according to screening ultrasound examination of the pelvic organs, only 7 patients directly in the maternity hospital (3 of them nulliparous and 4 multiparous) had subinvolution of the uterus and vacuum aspiration of the contents of its cavity was performed ( after manual examination of the uterine cavity - 0), followed by the prescription of antibacterial therapy with protected penicillins at a dosage of 1000 mg 2 times a day for 7 days.

The majority of patients (68%) were discharged on the 34th day in satisfactory condition. Later discharge (5-7 days - 32% of patients) was associated with the condition of the child.

14±8.9 days after birth, postpartum women began to complain of pain in the lower abdomen (45% of patients), increased blood discharge from the genital tract (57.6%), increased body temperature and other complaints (34.3%) , and therefore the patients were hospitalized in the hospital (Fig. 2).

All patients underwent a standard clinical and laboratory examination with a mandatory blood test for the content of C-reactive protein (CRP), procalcytonin, a detailed coagulogram with the study of the levels of D-dimer and fibrinogen, bacteriological and bacterioscopic examination of discharge from the cervical canal, uterine cavity, examination of the mammary glands, consultation of related specialists, transvaginal ultrasound of the pelvic organs.

According to the analysis of CRP and procalcitonin, in 15.7% of patients the level of CRP varied from 0.3 to 173 mg/l, the level of procalcitonin in 2 patients (2.6%) reached 2 ng/ml, which significantly exceeded the norm (up to 0.05 ng/ml) (see table).

According to bacteriological examination data, opportunistic gram-positive bacteria were isolated from the genitourinary tract in most cases (Staphylococcus epidermidis - 12.6%, Enterococcus faecalis

- 15.5%) and gram-negative (

Escherichia coli

- 26.9%) microorganisms (more than 104 CFU/ml), in 5% of studies - mixed infection, which influenced the choice of antibacterial therapy.

However, along with them Streptococcus aureus

(4.22%),

Streptococcus agalactiae

(2%) and

Klebsiella pneumonia

(1.4%) were detected.

Aggravating factors of the patients' condition: mild anemia in 13% of patients, moderate anemia in 8%, severe anemia in 3%, grade I hemorrhagic shock in 2% and grade II in 1%.

Treatment included complex antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, uterotonic, hemostatic therapy, physiotherapeutic procedures, lavage of the uterine cavity with antiseptic solutions (chlorhexidine, dioxidine), ultrasonic cavitation of the uterine cavity. Satisfactory treatment results without surgical intervention were achieved in 42 (59.2%) patients, of which 26 (35.5%) patients from group 1, 16 (23.7%) patients from group 2.

When prescribing antibacterial therapy before obtaining the results of a bacteriological study, preference was given to first-line drugs (taking into account the patients' continued lactation): groups of protected penicillins - amoxicillin + clavulanic acid at a dosage of 1000 mg 2 times a day (57 patients - 75%) and third generation cephalosporins - ceftriaxone at a dosage of 2 g per day (19 patients - 25%). If the ongoing antibacterial therapy was ineffective (8 patients - 11%), antimicrobial drugs of the fluoroquinolone group were prescribed or combination therapy was carried out (in 14%). If there was no effect from the therapy within 72 hours, drugs from the group of cabrapenems (menonem) were prescribed in 1.3% of patients and oxalidinones (linezolid) in 2.6% of those examined.

As hemostatic therapy and prevention of bleeding, tranexamic acid (100%) was used as a first-line drug in 100% of patients and eptacog alfa (in 6%) as a second-line drug in the event of massive coagulopathic bleeding.

In 26 of 75 patients (40.8%), vacuum aspiration of the contents of the uterine cavity was performed under intravenous anesthesia with mandatory ultrasound control. In 6 (5.6%) of them, due to heavy bleeding, the operation was performed urgently on the 1st day of hospitalization (5 primiparous, 1 multiparous), 20 (35.5%) - in a delayed manner, on the 2nd day from moment of admission after preliminary preparation in the form of antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, uterotonic therapy. In 5 patients, surgical treatment was performed due to the ineffectiveness of conservative therapy (4 nulliparous, 1 multiparous), which increased the length of the patients' stay in the hospital. In group 2, surgery was performed only on patients with spontaneous labor.

Comparative characteristics of groups of patients who underwent conservative and surgical treatment are presented in Fig. 3 and 4.

2 patients, due to the development of uncontrollable blood loss in a volume of >500 ml, underwent endovascular occlusion of the uterine and internal iliac arteries - 1 from the 1st group due to the ineffectiveness of instrumental evacuation of the uterine cavity, 1 from the 2nd group due to the ineffectiveness of conservative therapy.

According to the results of histological examination, remnants of placental tissue were found in 9 (11.8%) patients, and signs of acute endometritis were detected in 14 (18.4%) patients.

Cure criteria

: reduction in the intensity of blood discharge from the genital tract, normalization of laboratory parameters with their initial changes, satisfactory results of ultrasound of the pelvic organs.

Most of the patients were discharged within 5 days from hospitalization (61 patients - 80.2%), 15 (19.3%) patients spent up to 10 days in the hospital, 1 (1.3%) patient spent >10 days in the hospital. Additional factors for increasing length of stay are the severity of the disease, ongoing bleeding, which in 7 (10.5%) patients required additional transfusion of fresh frozen plasma and erythrocyte suspension, prescription of drugs for blood coagulation factors, and in 1 (1.3%) - observation in the conditions of intensive care unit.

Discussion

Based on the results of the analysis of the quality of treatment of patients with complications of the late postpartum period, 2 scenarios for the management and treatment of this group of patients were developed (Fig. 5, 6).

If the patient’s condition was stable (95.6%), preference was given to conservative therapy (44%) or (in the case of ultrasound signs of placental tissue remnants) preparation for delayed surgical treatment (9%).

Early detection of consumption coagulopathy followed by the standard prescription of crystalloid and colloid solutions, replenishment of the circulating blood volume depending on the volume of blood loss (its assessment is complicated by the lack of data on the amount of blood lost before admission to the hospital) made it possible to avoid unnecessary surgical intervention in 50% of patients.

According to our observations, if emptying the hematometra is ineffective, repeated intrauterine intervention, as well as transvaginal application of hemostatic clamps, is impractical and ineffective, therefore the next stage of treatment should be endovascular occlusion of the uterine and internal iliac arteries or, in the absence of the necessary equipment and specialists, ligation of these arteries by laparotomy access. In the case of occlusion or ligation of the uterine and internal iliac arteries, bleeding in 100% of cases stopped within the first hour from the moment of the operation; no relapses of bleeding were noted.

Thus, in our opinion, the main problems of late postpartum complications are the lack of a thorough assessment and prediction of risk factors for the development of complications already at the stage of the postpartum department of the maternity hospital with subsequent informing the outpatient department about this fact, personalized full prescription, and not only at the stage of the obstetric hospital, course of antibacterial therapy (if indicated) with mandatory informing the patient about the reasons and purposes of the prescription. In the late postpartum period, at the outpatient stage, it is important to limit the prescription of antibacterial therapy (taking into account the possibility of a high risk of complications) and refer patients for consultation and hospitalization in a hospital.