Dysgeusia (distortion of taste) is a disease in which the sense of taste is partially or completely absent. There are many reasons for this disease. Using the sense of taste, we can determine the taste of food and other elements entering the body. The sense organs that are responsible for this function are called taste buds.

They are located on the surface of the tongue. Under some conditions, a person may lose the ability to taste foods. Experts distinguish four main types of such disorders, namely pargeusia, dysgeusia, ageusia or hypogeusia. The complete absence of all taste sensations is called ageusia, partial weakening is called hypogeusia . Sometimes, a person constantly feels an unpleasant taste, regardless of the product he consumes. Distorted taste, which has a metallic taste, is a sign of dysgeusia.

Taste qualities with dysgeusia are distorted

Based on the above, taste qualities in dysgeusia are not completely absent, but are distorted. Some experts call dysgeusia (taste distortion) any taste disorder, while others use this term to mean a certain type of taste disorder. That is, dysgeusia is any change in taste, including a strange taste. No one is immune from the occurrence of taste deviations. They can occur at any age. People with dysgeusia constantly feel an unpleasant, salty, rancid or metallic taste in their mouth.

Even ice cream can have a salty or metallic taste. There are cases when people also experience changes in smell. Taste buds and receptors responsible for smell are interconnected, so this phenomenon is quite common.

Impaired sense of smell and taste is one of the most common symptoms of the new coronavirus infection. Changes in chemosensory function occur in the early days of the disease and may be the only symptom of COVID-19. Among the European population, olfactory dysfunction associated with COVID-19 occurs in 60–80% of cases, in East Asians - in 30%.

Elena Malets, scientific secretary of the research department of the Republican Scientific and Practical Center of Otorhinolaryngology, candidate of medical sciences. SciencesEtiopathogenesis

Smell impairment can develop in conductive and neurosensory types. Conductive dysosmia occurs due to swelling and inflammation of the nasal mucosa, accompanied by blockage of the olfactory cleft.

However, with COVID-19, this variant is rarely observed; the most characteristic is the neurosensory mechanism of dysosmia. SARS-CoV-2 infects the supporting cells of the olfactory neuroepithelium, on the surface of which receptors for angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 (ACE2) are located. After the spike protein binds to the ACE2 receptor, the virus enters the target cell by endocytosis using a type 2 transmembrane serine protease.

Receptor cells of the olfactory neuroepithelium do not contain ACE2; disruption of their functioning and damage to cilia occurs due to the death of supporting cells that perform protective and trophic functions. The role of ACE2, found on the cell membranes of the epithelium of the oral cavity and tongue, in impaired taste sensitivity in COVID-19 has also been proven.

Another molecular cellular mechanism of chemosensory disorders is also possible, due to the glycoprotein neuropilin-1, which is a potential receptor for coronavirus and is expressed in large quantities on neurons and endothelial cells of the capillaries of the olfactory bulb and olfactory tract (I pair of cranial nerves).

The involvement of the olfactory bulb in the pathological process was confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging data of the brain in patients with COVID-19: at the beginning of the disease, accompanied by anosmia, an increase in the volume of the olfactory bulb was noted and a significant decrease by the time the patient recovered and the olfactory function was restored.

Isolated damage to cranial nerves due to penetration of SARS-CoV-2 through the blood-brain barrier damaged as a result of a cytokine storm is currently being actively discussed. This may also explain the taste disturbance that develops as a result of damage to the taste fibers of the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX pair) and the chorda tympani, a branch of the facial nerve (VII pair).

Modern literature describes two mechanisms of smell: orthonasal and retronasal. The first mechanism is realized during normal nasal breathing, when air passes in a linear flow through the lower nasal passage. The retronasal mechanism is observed during the act of swallowing, followed by reflex exhalation. The exhaled air, together with the odorous substance, penetrates the olfactory cleft through the nasopharynx and choanae. The latter mechanism explains taste disturbances in many patients with coronavirus infection.

Clinical picture

Impaired sense of smell and taste (ICD-10: R 43) associated with COVID-19:

- anosmia - complete loss of smell;

- hyposmia - reduced ability to smell;

- parosmia - perverted perception of smells;

- phantosmia - sensation of smell in the absence of a stimulus;

- ageusia - complete lack of perception of taste sensations;

- hypogeusia - weakening of taste sensations.

Often, a violation of the sense of smell in 70–80% of cases is accompanied by a violation of taste, but can occur as a monosymptom. Isolated taste disturbance without olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19 is extremely rare (about 5–15%). Olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19 in 70–80% of patients occurs in the form of anosmia, hyposmia has been confirmed in 20–30%. Phenomena such as difficulty in nasal breathing and runny nose are not typical for COVID-19.

International associations of otolaryngologists urge that the sudden onset of loss of smell and/or taste be considered a specific diagnostic criterion for COVID-19 disease. It is argued that the first identified olfactory disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic are sufficient grounds for self-isolation of the patient and the mandatory use of PPE by both the patient and health care workers. Also, the importance of smell and taste sensitivity for the patient should not be underestimated, since chemosensory dysfunction not only reduces the quality of life, but can also lead to severe neurological and neuropsychiatric complications (for example, depression, cognitive impairment, etc.).

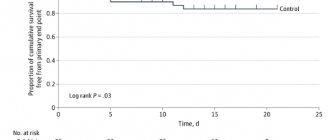

In most cases, restoration of olfactory function occurs spontaneously within one month during treatment of the underlying disease. No additional treatment measures are required.

60–70% of patients with COVID-19 note an improvement in their sense of smell on the 8–9th day of the disease; in 80–90%, complete recovery is observed by the 15th day. And only 10–15% of patients are forced to seek medical help from an otolaryngologist due to the lack of smell and/or taste for more than 20 days. The presented time data for the restoration of olfactory function are explained by the pathophysiological mechanisms occurring in the olfactory epithelium under the influence of SARS-CoV-2. Stem cells provide regeneration of supporting cells by the 7th day of the disease, and restoration of cilia of receptor cells is noted on the 8th–9th day.

Full functioning of the olfactory neuroepithelium becomes possible on the 15th day from the onset of the disease. It is assumed that long-term anosmia (more than 15–20 days) is due to possible damage to the olfactory receptor cells themselves, the natural recovery period of which can take up to 2 months.

The mechanism of smell impairment in COVID-19.

See the continuation of the material here.

Causes of taste disturbance

There are contact and neural taste disorders. In the first case, the contact of the taste stimulus with the potentially functioning taste bud is disrupted. In the second, a taste stimulus comes into contact with the taste bud, but either the function of its receptor is impaired (for example, with blockade of sodium, potassium channels, with atrophy of the papillae), or the transmission of information or its processing due to neural damage. A combination of both types of damage is possible. In table 1 presents the most common conditions accompanied by taste disturbances.

The most common causes of taste disturbances are: respiratory pathology (upper respiratory tract), side effects of medications, oral diseases, aging, endocrine and metabolic disorders, diseases, middle ear injuries and surgical interventions, xerostomia.

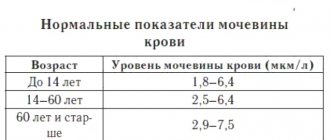

The loss of taste with age occurs more in relation to salty and bitter than in sweet. Atrophy of taste buds during aging is accelerated by heavy smoking and intake of irritating substances. Patients with renal pathology have an increased threshold for sweet and sour compared to healthy people. The change in the sensitivity threshold decreases after dialysis.

Disturbances in the sense of taste often accompany endocrine diseases. In patients with hypothyroidism, a decrease in the pungency of taste can be detected, and in patients with hyperthyroidism, an increase. After effective treatment, these symptoms disappear. In diabetes mellitus, hypogeusia is possible, presumably due to peripheral neuropathy. A significant exacerbation of taste sensations occurs with adrenal insufficiency, which is most likely associated with electrolyte imbalance - with severe hyperkalemia, hyponatremia and changes in the function of taste buds. Hypergeusia is treated with corticosteroid replacement therapy. The severity of taste depends on the excess of female sex hormones - it intensifies during pregnancy. Along with this, testosterone-producing virilizing tumors of the adrenal cortex may be accompanied by hypertrophy of the taste buds and an exacerbation of taste.

Some patients report a feeling of bitterness in the mouth. This can be not only fantasy, but also a true perception of bitter taste. It can occur in diseases of the liver and biliary system, accompanied by changes in the composition of saliva, which closely correlates with the composition of blood serum. With gastroesophageal reflux disease and bile reflux, there may also be a feeling of bitterness in the mouth in the morning due to the greatest severity of reflux with a horizontal body position.

Many medications cause taste disturbances. In some cases, the mechanism of this effect is unclear, in others (for example, taking cytostatics) the perception of taste is impaired due to atrophy of the papillae, in others (for example, drugs) - as a result of an effect on the taste centers or as a result of a combination of contact and neural disorders. Many medications (eg, anticholinergics, some antidepressants, antihypertensives) reduce salivary flow, which may lead to decreased sense of taste, especially with long-term treatment. Antibiotics often cause an imbalance in microflora, which in itself can cause taste dysfunction (for example, a feeling of “unpleasant” taste in the mouth). Often, even after short-term use of antibiotics, candidiasis develops, including damage to the tongue, palate, and hypogeusia occurs.

A common side effect of drug treatment is phantageusia, which is a metallic taste in the mouth.

Another type of phantageusia - a burning sensation of the tongue - is a characteristic symptom of vitamin B 12 deficiency anemia, apparently arising due to both glossitis (then the burning sensation is the equivalent of pain) and myelopolyneuritis. A burning sensation of the tongue (possibly also of the lips and palate) sometimes precedes a change in the blood. It may be accompanied by hypogeusia.

A burning sensation of the tongue (as the equivalent of pain) is possible with glossodynia. In these cases, a similar sensation sometimes appears in other areas - on the hard palate, the mucous membrane of the lips. It is usually bilateral and can be combined with hypo-, ageusia, and “dry mouth.” Glossodynia is not associated with any local pathology or general diseases, but is more common in people with depression and postmenopausal women.

Because of the bilaterality and multiple innervation of taste receptors, complete loss of taste is rare. Hypogeusia is more common.

In case of pathology of the nervous system, diseases of the middle ear, after surgical trauma, taste disturbances are unilateral, in case of systemic diseases, lesions of the oral cavity - bilateral.

Treatment

Treatment of taste disorders is the treatment of the diseases that caused them. The prognosis for restoration of taste is determined by the prognosis of this disease. Thus, treatment of metabolic disorders can lead to the restoration of taste. The underlying diseases such as oral candidiasis or pemphigus can be eliminated and taste function is normalized. In a patient with a section of the chorda tympani during middle ear surgery, even unilateral taste disturbance can lead to a decrease in quality of life.

Repeated taste testing of a patient with a potentially reversible cause of dysfunction allows a rough estimate of the prognosis for its recovery.

An important component of the treatment of patients with diagnosed taste loss are the following recommendations: maximizing the density of food, maximizing the smell and taste of food, and protecting food from spoilage. The first advice is to inform the patient about the ability of the tongue to detect trigeminal stimuli, such as food density, temperature, and pungency. Patients who adopt this recommendation may experience improved perception and enjoyment of food, increasing these sensations. The essence of the second tip is to teach the patient to enjoy the smell of food. The third recommendation, which should become a rule, is to eat only obviously fresh, good-quality food and carefully monitor its safety in the refrigerator. Otherwise, after removing food from the refrigerator, you can quickly use it without knowing that it has spoiled.