Etiology

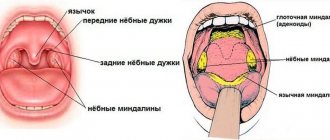

Schematic representation of the options for the spread of the abscess (horizontal cut of the lower third of the head): 1 - medial pterygoid muscle: 2 - branch of the lower jaw;

3 - chewing muscle; 4 - parotid gland; 5 — fiber of the peritonsillar space (areas of peritonsillar and peripharyngeal abscesses are shaded, a straight arrow indicates the direction of the peritonsillar abscess breakthrough); 6—long muscles of the head and neck: 7—palatine tonsil; 8 - peri-amygdaloid fiber; 9 - buccal muscle (arrows indicate the path of spread of the peripharyngeal abscess). In most cases O. a. is a complication of acute naratonsillar abscess. It can occur as a result of the breakthrough of pus from the abscess of the tonsil itself into the paratonsillar and then peripharyngeal space (Fig.), sometimes O. a. develops as a result of trauma to the pharynx or after tonsillectomy. The cause of O. a. There may be certain forms of mastoiditis, for example, Bezold's mastoiditis (see Mastoiditis).

The causative agents of O. a. most often are streptococci, spindle bacillus, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, etc. The infection spreads through the lymphatic, venous and contact routes. At first the process is diffuse, then an abscess forms.

Causes of paratonsillar abscess

As a rule, a paratonsillar abscess develops as a complication of tonsillitis or chronic tonsillitis. With tonsillitis, scars can form in the tonsils, preventing pus from leaving the lacunae (lacunae are natural narrow and highly branched cavities in the body of the tonsil). Pus that does not find a way out accumulates inside, from where it penetrates into the tissue surrounding the tonsil.

Clinical picture

The general condition of the patient is serious: body temperature is increased to 40-41°, there is severe pain in the throat, radiating to the ear, dysphagia (see), trismus (see), severe pain when trying to open the mouth.

There may be a forced position of the head tilted to the painful side, head movements are sharply painful.

In the blood, leukocytosis is determined (up to 20,000 and above), a shift in the leukocyte formula to the left, and accelerated ROE.

If the infection spreads through the internal venous pterygoid plexus into the cranial cavity, purulent meningitis may develop (see). The spread of infection through the inferior orbital vein can cause thrombosis of both this vessel and the cavernous sinus with the subsequent development of sepsis (see). Sepsis can also develop as a result of jugular vein thrombosis. Possible swelling of the larynx with symptoms of laryngostenosis (see). The spread of infection along the vascular bundle of the neck can cause the development of purulent mediastinitis (see), often posterior. Cases of Ludwig's angina (see Ludwig's angina), osteomyelitis of the mandible and cervical vertebrae are described.

Diagnosis

Upon examination and palpation, a painful swelling is determined behind and downward from the angle of the lower jaw, pain along the vascular bundle. The angle of the lower jaw cannot be felt. With pharyngoscopy (see), protrusion (displacement to the midline) of the lateral wall of the pharynx, tonsil and palatine arches is determined.

When rentgenol, examination of the neck on a lateral radiograph reveals an anterior displacement of the trachea, especially if the infection has spread from the pharynx. Sometimes gas bubbles are detected in soft tissues.

general description

Retropharyngeal abscess (J39) is a purulent inflammation of the lymph nodes, loose tissue located between the fascia of the pharyngeal muscles and the prevertebral fascia.

Develops mainly in childhood (the retropharyngeal space up to 4-5 years is rich in lymph nodes and loose fiber). In adults, this disease is very rare and is secondary; leak in case of tuberculous, syphilitic inflammation of the upper cervical vertebrae, in case of their injury.

Causes: infection of the lymph nodes of the retropharyngeal space due to nasopharyngitis, tonsillitis, measles, diphtheria, scarlet fever, acute purulent otitis media; due to trauma to the posterior pharyngeal wall, adenotomy.

Predisposing factors: metabolic disorders, decreased immune reactivity of the body, malnutrition.

Treatment

With O. a. hospitalization is required. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are prescribed and the underlying disease is treated. As a rule, surgery is indicated.

O. a. opened from the pharynx (usually after a tonsillectomy) or with an external incision. If there is a fistula in the tonsil niche, it is expanded. When opening O. a. from the side of the mouth, the incision is made laterally from the pterygoid hook from top to bottom. After dissection of the mucous membrane, the tendons of the medial pterygoid muscle are discovered. They bluntly penetrate between this muscle and the wall of the pharynx into the peripharyngeal space, taking into account the risk of damage to the lingual nerve.

During an operation with an external incision, the skin and superficial fascia of the neck are cut along the anterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle so that its middle corresponds to the angle of the lower jaw. Somewhat below this angle, a site is found where the tendon of the digastric muscle pierces the muscle fibers of the stylohyoid muscle. Over these muscles, they pass bluntly in the direction of an imaginary line running from the angle of the jaw to the tip of the nose, and separate the tissues of the peripharyngeal space, examining the area corresponding to the position of the palatine tonsil, the area of the styloid process and the stylohyoid muscle.

In the peripharyngeal space, serous, purulent, putrefactive or necrotic changes are found, depending on the nature of the inflammation. Sometimes putrefactive inflammation occurs with the formation of gas and an unpleasant odor. In some cases, necrosis of not only the fiber, but also the fascia is possible. Sometimes the abscess is delimited by granulation tissue.

If thrombosis of the internal jugular vein is suspected, a skin incision is made along the anterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, its bed and the sheath of the vascular bundle of the neck are opened. The tissues surrounding the vascular bundle and the lateral wall of the pharynx are bluntly separated. If necessary, the jugular vein is ligated and penetrated into the connective tissue behind the clavicular and sternal attachments of the sternocleidomastoid muscle.

The operation is completed by drainage of the peripharyngeal space. In the postoperative period, antibiotics and sulfonamides are prescribed, and anti-gangrenous serum is administered according to indications.

Retropharyngeal abscess (retropharyngeal abscess): symptoms, diagnosis, treatment

- 6.1 Airway compromise

Retropharyngeal abscess

A retropharyngeal abscess (RPA) is an infection of the neck with the formation of an abscess in the space between the prevertebral fascia and the constrictor muscles. The condition most often occurs in children, but its incidence is increasing in adults.

Etiology Residual effects of upper respiratory tract infections (eg, pharyngitis, tonsillitis, sinusitis, dental infections) represent 45% of cases of HRA. The most common organisms that cause the disease include Streptococcus viridans, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus epidermidis, and beta-hemolytic streptococci.

Less common causes include Veillonella spp., Bacteroides melaninogenicus, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. There are also reports of infections caused by both methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Normal upper respiratory tract commensals can become pathological causative organisms in the case of GAD. Accidental trauma to the retropharyngeal region, such as foreign body ingestion (in a child running with a piece of candy in his mouth), falling, or swallowing sharp objects such as chicken bones, is associated with 27% of cases of PGA. The remaining 28% are idiopathic.

Pathophysiology

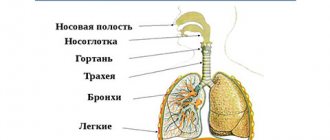

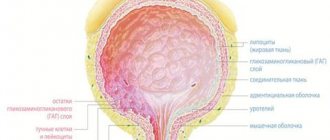

The retropharyngeal space is located immediately in front of the prevertebral fascia, which extends down from the base of the skull along the pharynx. It is connected to the parapharyngeal space and the infratemporal fossa. The retro- and parapharyngeal spaces are separated by the pterygoid fascia, which is likely an ineffective barrier to the spread of infection. Because the retropharyngeal space is connected to the superior and posterior mediastinum, it is a potential route for infection to spread into the chest.

The retropharyngeal space contains loose fibrous connective tissue and lymphatic networks that allow the pharynx and esophagus to move during swallowing. The circulation of lymph through the spaces originates from the tissues of the nasal cavity, paranasal sinuses, Eustachian tubes and adjacent tissues of the pharynx. Often, the formation of pus in the retropharyngeal lymph nodes is well contained and, therefore, vertical spread of infection can occur late in the progression of the disease, although in practice this is rare.

Most symptoms and signs of PGA are associated with increasing upper gastrointestinal and respiratory obstruction and irritation of local muscle groups (eg, sternomastoid and pterygoid).

Step-by-step diagnostic approach

Although history and examination are key in identifying PGA, imaging or spontaneous or surgical drainage of the abscess confirms the diagnosis.

Anamnesis

A thorough history is important because differential diagnoses include other serious conditions. Most often, HGAs are residual effects of upper respiratory tract infections (eg, pharyngitis, tonsillitis, sinusitis, dental infections). Most often they occur in children; therefore, you need to pay attention to the history of foreign body ingestion.

In children, manifestations may be vague and depend on the stage of the disease, but characteristic symptoms include fever with peaks of temperature, neck pain (especially with movement) or torticollis, and dysphagia. Other common symptoms include irritability, weakness, mild photophobia, and odynophagia (pain when swallowing). Odynophagia can cause drooling, decreased oral intake of food and fluids, and anorexia. Less common symptoms include trismus (spasm of the masticatory muscles), dysphonia (hoarseness), stridor, or sleep apnea. You may also see your child reaching for their ears or throat, which indicates pain.

In adults, manifestations may be more specific, with drooling and dysphagia, but their progression is usually more gradual. It is important to learn about comorbidities such as diabetes and, if present, optimize glycemic control. About a third of patients with deep neck abscesses have diabetes.

Airway obstruction usually manifests as symptoms such as shortness of breath, difficulty breathing, and weakness. Patients with a complicated clinical course are more likely to present with signs of airway obstruction or multiple abscesses compared with patients with an uneventful clinical course.

Physical examination

An attempt should be made to examine the mouth and neck for enlarged tonsils, swelling of the oropharyngeal tissue, and lymphadenopathy. Other important observations may include drooling, shortness of breath, torticollis, and swelling/mass in the neck. In children, examination may be limited depending on the age and cooperation of the child (and parents).

Airway compromise usually manifests as tachypnea, cyanosis, tracheal pulsation, or intercostal retraction. High respiratory rate and oxygen saturation are useful in diagnosing airway obstruction.

Laboratory research

OAC with formula should be prescribed primarily to confirm neutrophilia. You can also determine ESR to determine the severity of the inflammatory disease in the absence of pronounced neutrophilia. Typically, bacteriological blood tests are not performed unless sepsis is suspected.

Visualization methods

X-ray studies are necessary to confirm the diagnosis. The choice of investigation depends on the degree of suspicion and the availability of various imaging modalities, as well as the severity of the case. However, CT is the definitive study and, if performed with contrast, will show a ring-shaped lesion in the retropharyngeal tissues accumulating contrast.

If there is concern about the airway or the possibility of surgical drainage, consideration should be given to sedation and intubation of the child before CT scanning with the prospect of transfer to the operating room.

Ultrasound and plain radiographs of the neck show some signs of PHA, but these methods are less sensitive and less specific than CT. They should only be used in cases where CT is not available.

MRI is not used to diagnose this condition because CT provides an obvious result in most cases and is usually a more accessible and cheaper resource.

Surgical intervention

Examination under anesthesia (EA) should be performed if there is a strong suspicion of PGA and airway compromise, or if a CT scanner is not available. Also, PPA should be performed if CT (or other imaging modalities in the absence of CT) was performed and the result is consistent with PGA. OPA allows you to confirm the diagnosis and perform transoral opening and drainage. If possible, a sample of pus should be taken during drainage for bacteriological examination and sensitivity testing.

Risk factors

- Foreign body ingestion Children with a history of foreign body ingestion are at high risk. The suspicion must be significant, especially if the object was sharp.

- Penetrating trauma to the posterior wall is a well-recognized cause. The possibility of intentional injury should be considered.

- A previous odontogenic infection suffered by the patient may predispose to the formation of PHA.

- About a third of patients with deep neck abscesses suffer from this condition.

Differential diagnosis

| Disease | Differential signs/symptoms | Differential examinations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| • Clinical examination confirms the presence of infected tonsils with a normal posterior pharyngeal wall. | The diagnosis is made clinically. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Treatment

The treatment is therapeutic. If this fails, surgery is required with consultation of an otolaryngologist. All patients must be hospitalized. Safe and proper management of the airway is important when the airway is in danger. This is usually achieved through conservative or surgical means. Treatment primarily depends on the severity of respiratory distress.

Airway compromise

If a retropharyngeal abscess (RPA) is strongly suspected and the airway is compromised (as evidenced by stridor, tachypnea, and decreased oxygen saturation as the patient becomes fatigued), the patient should be immediately admitted to the hospital. Initial medical treatment includes the use of corticosteroids and antibiotics. If they do not provide rapid relief, the patient should be immediately transferred to the operating room for examination under anesthesia with the prospect of surgical drainage.

Intubation or airway surgery, such as tracheostomy, may be necessary and should be performed by an experienced pediatric or adult anesthesiologist. Fiberoptic intubation sometimes helps prevent abscess rupture in these cases and helps obtain a good view of the airway. If the tube is not cuffed, it is helpful to insert a bag that allows the back of the throat to be visible for surgical access.

If XRF is confirmed by surgical exploration (posterior oropharyngeal bulging and/or aspiration of purulent fluid), the surgeon should perform a transoral incision and drainage. The cultures are collected and sent to the laboratory. In cases where there is extension to the posterior mediastinum, drainage of purulent secretions and removal of necrotic material from the pericardial area and pleural space may be necessary.

If the airway is still unstable, the patient should be closely monitored in the intensive care unit and started on empirical intravenous antibiotics; Prolonged intubation may be required. Patients with a stable airway after surgery should also be started with empirical intravenous antibiotics.

Airway patency is not impaired

Even if the airway is not compromised, the patient should be hospitalized. If the airway is not an immediate problem and there is no evidence of mediastinal abscess spreading, treatment with empiric intravenous antibiotics for 24 to 48 hours should begin immediately.

Corticosteroids can be used in combination with intravenous antibiotics. The patient undergoes a CT scan. Prompt treatment with antibiotics, with or without corticosteroids, may resolve or prevent disease progression in some patients caught early in the disease (when only cellulitis and not a true abscess has formed), thereby avoiding the need for surgical drainage.

Failure of initial medical treatment (eg, lack of improvement in symptoms, continued intermittent fever, deterioration of vital signs) and/or the presence of an imaging-determined abscess should prompt a PPA with the prospect of oral surgical drainage. Repeat CT imaging may be required to assess progression of the abscess. In children, anesthesia is preferred before CT scanning, whereas adults usually tolerate imaging without anesthesia. After surgical drainage, intravenous antibiotics should be continued, either as an empirical regimen or according to susceptibility data, if available.

Empirical antibiotic therapy

The spectrum of antibiotic activity should cover the most common organisms: Streptococcus viridans, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus epidermidis and beta-hemolytic streptococci. Less common causes include Veillonella species such as Bacteroides melaninogenicus, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Normal upper respiratory tract commensals can become pathological causative organisms in the case of GAD.

Typical antibiotic regimens include ampicillin/sulbactam, clindamycin, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, metronidazole, and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. Combination regimens of these antibiotics may be necessary to adequately cover the likely organisms (eg, ceftriaxone plus metronidazole or clindamycin plus cefuroxime).

Metronidazole will cover anaerobic bacteria as there may be a connection with the parafarnic space and therefore with the oral cavity. Clinical improvement should be observed within 24–48 hours; otherwise, the patient should be re-evaluated. The spectrum of antibiotic activity can be expanded. In refractory cases, the presence of atypical mycobacteria or MRSA should be suspected. Empiric antibiotics should be continued until the patient becomes afebrile or cannot tolerate oral medications to complete the 14-day course. Patients can be switched to culture-based targeted therapy if drainage is performed.

Symptomatic therapy

It is necessary to monitor the condition of the patients' respiratory tract throughout treatment. Adequate intravenous hydration and nutrition should be given until oral consumption of food and beverages is possible. Some patients may require analgesia. Patients should be closely monitored for complications.

List of sources

- BMJ

- Jennings CR. Surgical anatomy of the neck. In: Gleeson M, Hilbert JS, eds. Scott-Brown's otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery. 7th ed. London: Hodder Arnold; 2008:1744-1745.

- Gaglani MJ, Edwards MS. Clinical indicators of childhood retropharyngeal abscess. Am J Emerg Med. 1995 May;13(3):333-6.

- Wajn J, von Buchwald C, Arndal H. Late diagnosis of retropharyngeal abscess in an infant. Ugeskr Laeger. 1993 Jul 12;155(28):2211-2.

- Wang LF, Tai CF, Kuo WR, et al. Predisposing factors of complicated deep neck infections: 12-year experience at a single institution. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010 Aug;39(4):335-41.

- Wang LF, Kuo WR, Tsai SM, et al. Characterizations of life-threatening deep cervical space infections: a review of one hundred ninety-six cases. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003 Mar-Apr;24(2):111-7.

- Philpott CM, Selvadurai D, Banerjee AR. Paediatric retropharyngeal abscess. J Laryngol Otol. 2004 Dec;118(12):919-26.

- Christoforidou A, Metallidis S, Kollaras P, et al. Tuberculous retropharyngeal abscess as a cause of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Am J Otolaryngol. 2012 Mar-Apr;33(2):272-4.

- Abdel-Haq N, Quezada M, Asmar BI. Retropharyngeal abscess in children: the rising incidence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2012 Jul;31(7):696-9.

- Kirse DJ, Roberson DW. Surgical management of retropharyngeal space infections in children. Laryngoscope. 2001 Aug;111(8):1413-22.

- Morrison JE Jr, Pashley NR. Retropharyngeal abscesses in children: a 10-year review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1988 Mar;4(1):9-11.

- Ungkanont K, Yellon RF, Weissman JL, et al. Head and neck space infections in infants and children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995 Mar;112(3):375-82.

- Parhiscar A, Har-El G. Deep neck abscess: a retrospective review of 210 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001 Nov;110(11):1051-4.

- Byramji A, Gilbert JD, Byard RW. Fatal retropharyngeal abscess: a possible marker of affected injury in infancy and early childhood. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2009 Dec;5(4):302-6.

0 0 votes

Article rating

Forecast

With timely opening of O. a. and the use of active antibacterial therapy, the prognosis in most cases is favorable.

Bibliography:

Multi-volume guide to otorhinolaryngology, ed. A. G. Likhacheva, vol. 3, p. 327, M., 1963; Preobrazhensky B.S. and Popova G.N. Angina, chronic tonsillitis and associated diseases, p. 164, M., 1970; Surgical diseases of the pharynx, larynx, trachea, bronchi and esophagus, ed. V. G. Ermolaeva et al., p. 65, M., 1954; Ballantyne J. a. Groves J. Scott-Brown's diseases of the ear, nose and throat, v. 4, p. 70 ao, L., 1971; Ballenger WL a. Ballenger H. Ch. Diseases of the nose, throat and ear, p. 324, Philadelphia, 1947; Falk P.u. Maurer H. Die entztindlichen Erkrankungen des Ra-chens, in the book: Hals-Nasen-Ohrenheilkunde, hrsg. v. J. Berendes ua, Bd 2, T. 1, S. 71, Stuttgart, 1963.

Yu. B. Preobrazhensky.

Incidence (per 100,000 people)

| Men | Women | |||||||||||||

| Age, years | 0-1 | 1-3 | 3-14 | 14-25 | 25-40 | 40-60 | 60 + | 0-1 | 1-3 | 3-14 | 14-25 | 25-40 | 40-60 | 60 + |

| Number of sick people | 0 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |