Lymphoma is a malignant disease that affects the lymphatic system. More precisely, we are talking about a group of diseases, because there are several of them - and they differ in different features.

The lymphatic system itself is a complex system whose vessels cover all internal organs. It also includes lymph nodes, which form lymphocytes, which are very important for our immunity. This system has several key functions. The barrier cleanses the lymph and traps particles undesirable for the body (for example, dead cells). The transport function delivers nutrients to the organs, and the immune function helps fight viruses, bacteria, and any harmful cells.

If lymphoma develops, lymph cells begin to divide uncontrollably, tumors appear, which, without timely treatment, threaten the patient with death.

What is lymphoma?

Lymphoma is a lesion of the immune system and internal organs, in which altered cells accumulate, disrupting tissue function.

The tumor develops in the lymphatic system, which helps us fight infections and other diseases. The lymph circulating in it washes all the cells of the body and delivers the necessary substances to them, taking away waste. In the lymph nodes located throughout its network, dangerous substances are neutralized and removed from the body. The lymphatic system complements the circulatory system and helps fluids move throughout the body. Unlike blood, the speed of which is set by the “pump” - the heart, lymph slowly circulates on its own.

Treatment of mature T- and B-cell lymphomas

For the treatment of mature cell lymphomas, strict but short-term treatment (up to six months) is used using high-dose chemotherapy and immunotherapy (Fig. 2).

Treatment is carried out in short intensive courses - from 2 to 6. Their number depends on the stage of the disease and the risk group of the child. To determine the risk group, parameters such as the radicality of the operation (if any), the size and location of the tumor, the level of LDH in the blood and damage to the bone marrow and central nervous system are taken into account.

For the treatment of mature B-cell lymphomas, the cells of which express the CD20 antigen, the targeted drug rituximab (Mabthera, Acellbia) is used.

Rice. 2. NHL-BFM protocol for the treatment of mature B-cell lymphomas

How does lymphoma develop?

Oncology begins with the appearance in the body of just one altered cell of the immune system. In total, there are 2 main types:

- B lymphocytes

: produce antibodies - proteins that protect the body from bacteria and viruses. This is where most lymphomas form. - T lymphocytes

, one part of which destroys germs and abnormal cells, and the second helps to increase or slow down the activity of the immune system.

Almost all abnormal cells are identified and destroyed by our immune system, but some of them manage to survive. They gradually multiply, spread throughout the body, create tumors, accumulate in internal organs and disrupt their functioning.

The disease can occur in any area where lymphatic tissue is located, the main areas of which are:

- Lymph nodes

are small, pea-sized organs that are collections of cells of the immune system, including lymphocytes. There are more than 500 of them in the human body. - The spleen

, located under the lower ribs on the left side of the body. It produces lymphocytes, stores healthy blood cells and filters out damaged ones, and destroys microbes and foreign substances. - Bone marrow is

the spongy tissue inside certain bones. Here new blood cells are formed, including some lymphocytes. - The thymus, or thymus gland, is

a small organ located behind the upper part of the sternum in front of the heart. It is where some lymphocytes mature and develop. - Tonsils, or tonsils, are

collections of lymphatic tissue in the back of the throat. These organs help produce antibodies, proteins that prevent inhaled or ingested microorganisms from multiplying. - Digestive Tract:

The stomach, intestines and many other organs also contain lymphatic tissue.

Course of the disease during pregnancy

Lymphosarcoma can be combined with pregnancy. The following options are possible:

- Conception occurred in a state of remission.

- The tumor was detected during intrauterine development of the fetus.

- The tumor relapsed during pregnancy.

Pregnancy and childbirth during a period of stable remission do not aggravate the prognosis of the tumor. However, the risk of recurrence of lymphosarcoma is much higher for those patients in whom conception occurs during the first 2-3 years after complete stabilization of the condition. In this regard, women should be warned about the need to use contraceptives during this period.

High-risk lymphosarcoma, which was diagnosed in the first trimester, is an indication for termination of pregnancy. If a tumor is detected in the second and third trimester, management tactics are selected individually, with the involvement of specialists such as an oncologist, neonatologist, therapist, and geneticist. The extent of the disease and the nature of the response to treatment are taken into account.

If the tumor recurs, the prognosis for pregnancy is the most unfavorable. In this situation, the use of highly toxic drugs is required, the use of which is incompatible with pregnancy.

Is lymphoma cancer?

Official medicine in Russia and some other countries refers to cancer as malignant tumors - life-threatening neoplasms that develop in epithelial cells contained in the skin or mucous membranes and lining the internal surface of organs.

Lymphoma is not a cancer, but an oncological disease. It is formed from lymphocytes, and its cells are also able to divide uncontrollably, accumulate in tissues, disrupting their work, and create additional foci of disease in various parts of the body.

Treatment of lymphoblastic lymphomas from T- and B-precursors

Treatment of children with lymphoblastic lymphoma is long-term, continuous for 2 years. It consists of several successive phases: prophase, induction - protocol I, consolidation - protocol M, reinduction - protocol II, prevention of damage to the central nervous system. Rice. 3.

To prevent damage to the central nervous system, the introduction of chemotherapy into the spinal canal and radiation therapy are used. Maintenance therapy is carried out for 1.5 years.

The intensity of the treatment program depends on the stage of the disease.

Rice. 3. NHL-BFM protocol for the treatment of lymphoblastic lymphomas from T- and B-precursors

Types of lymphomas

Doctors distinguish 2 main classes of them:

- Hodgkin's lymphoma, or lymphogranulomatosis

: Most often starts in the lymph nodes of the upper body - in the chest, neck or armpits. It usually spreads to various lymph nodes through the lymphatic vessels, but in rare cases, in later stages it enters the bloodstream and spreads to other parts of the body, such as the liver, lungs or bone marrow. This diagnosis is made when special cells are identified in the body - Berezovsky-Reed-Sternberg, which are modified B-lymphocytes.

- TO non-Hodgkin's lymphomas

include all other types of the disease - there are about 30 of them. Each of them has its own special characteristics: the location of the primary tumor, the structure and speed of development.

Prevention

Lymphoma, which can cause symptoms in adults for a variety of reasons, can be prevented by following certain guidelines. Prevention will help reduce the risk of damage to the body to zero.

For this purpose it is necessary:

- less contact with toxic substances;

- do not neglect contraceptives during sexual intercourse with a casual partner;

- undergoes a course of vitamin therapy at least 2 times a year;

- maintain hygiene (do not use other people’s toothbrushes or towels);

- exercise regularly (moderately, at least 10-15 minutes will be enough).

Causes of lymphoma development

Doctors and scientists do not know exactly why the disease begins to develop in the human body. They only know about the factors that increase the likelihood of developing each type of cancer.

For Hodgkin's lymphomas

they look like this:

- Epstein-Barr virus

, which causes infectious mononucleosis - damage to lymphoid tissue, including adenoids, liver, spleen and lymph nodes. In some patients, parts of the virus are found in Berezovsky-Reed-Sternberg cells, but in most patients there are no signs of it. - Age

: Diagnosis can be made at any age, but it is most common in 20-year-olds and people over 55. - Gender

: The disease is more common among men than among women. - Heredity and family history

: The risk is increased for siblings and for identical twins. Identical twins develop from a single egg fertilized by a single sperm. They come in only one gender, have the same genes and are extremely similar in appearance. owners of Hodgkin's lymphoma. The reason for this is not exactly known - perhaps the whole point is that members of the same family suffer the same infections in childhood, or have common inherited gene changes that increase the likelihood of developing this type of oncology. - Weakened immune system

. The chances of receiving this diagnosis increase in people with HIV infection and disorders of the immune system, which develop, among other things, due to the use of drugs that suppress it, which is often required after an organ transplant.

List of such factors for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas

looks different:

- These include exposure to radiation

, including doses received during radiation therapy used to treat other types of cancer. - Various substances

, including herbicides and insecticides that kill weeds and insects, as well as chemotherapy drugs. - Age

: as a rule, the older the person, the higher his risks - in most cases the disease occurs at the age of 60+, but some types also occur in younger people. - Malfunctions of the immune system

affect the chances of developing all types of lymphomas. - Some viruses

can influence the DNA of lymphocytes, which encrypts all the information about our body, and convert them into cancer cells. - Infections that constantly stimulate the immune system and force our natural defenses to work harder also increase the risk of receiving a serious diagnosis.

- Having close blood relatives - parents, children, brothers or sisters - with this diagnosis also increases the likelihood of developing the disease.

- Some studies have shown that breast implants, especially those with a rough surface, may cause anaplastic large cell lymphoma. It develops on the skin, lymph nodes, or scar tissue formed at the site of the incision.

Incidence of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (NHL)

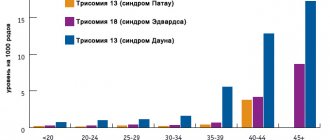

More than 90% of NHL is diagnosed in adult patients. Most often, NHL occurs between the ages of 60 and 70 years. The risk of developing this tumor increases with age.

The lifetime personal risk of developing NHL is approximately 1 in 50.

Since the beginning of the 70s, there has been an almost twofold increase in the incidence of NHL. This phenomenon is difficult to explain. This is mainly associated with infection caused by the human immunodeficiency virus. Part of this increase can be attributed to improved diagnostics.

Since the late 90s, there has been a stabilization in the incidence of NHL.

NHL is more often detected in men compared to women.

In 2002, 5,532 cases of NHL in adult patients were identified in Russia.

In the United States in 2004, according to preliminary data, 53,370 cases of NHL in adults and children are expected.

Symptoms and signs of lymphoma

As a rule, in the early stages this type of oncology does not manifest itself in any way, and its owner feels well and is not aware of the disease - almost all of its symptoms appear later, in advanced stages.

One of the most common signs is the appearance of swelling in the neck, armpits, groin, or above the collarbone.

, which is an enlarged lymph node. Typically, such a tumor does not hurt, but over time it often increases, and new lumps appear next to it or in other areas of the body.

Lymphomas that begin to develop or grow in the abdominal cavity can cause swelling

or

abdominal pain, nausea,

and

vomiting

. Such sensations occur due to enlargement of the lymph nodes or internal organs, such as the spleen or liver, or the accumulation of large amounts of fluid.

An enlarged spleen can put pressure on the stomach, causing loss of appetite.

and

a feeling of fullness after a small amount of food

.

Enlarged thymus Thymus, or thymus gland -

a small organ located behind the upper part of the sternum in front of the heart.

It is where some lymphocytes mature and develop. or lymph nodes in the chest may put pressure on the trachea, which carries air to the lungs. This leads to coughing

,

difficulty breathing, pain

or

heaviness in the chest

.

Brain lesions can cause headaches, weakness, personality changes, and problems with thinking

and

seizures

.

Other types of the disease can spread to the tissues surrounding the brain and spinal cord, causing the patient to see double and have a numb face

and

speech deteriorates

.

Lymphomas of the skin often appear as itchy red bumps

or

cones

.

In addition, symptoms may include:

- weight loss;

- chills;

- night sweats;

- elevated temperature;

- severe fatigue;

- bloating;

- frequent or severe infections;

- Easy bruising or bleeding.

When to see a doctor

Of course, if fatigue and some other symptoms occur separately, you should not immediately attribute this to the onset of oncology. It is necessary to undergo tests in order to understand the cause of the malaise.

Before taking the tests, you need to prepare. A day before all procedures, a person eliminates alcohol and tobacco. The stomach should be empty. The time of the last meal is at least 12 hours. It is forbidden to drink tea, juices (natural and purchased), and chew chewing gum. Only drinking water is allowed.

Another important condition is that you should not worry before the procedures. Sometimes it is difficult to prevent absolutely all factors that provoke stress. The most common cause of anxiety is waiting for a bad test result.

If a person is taking any medications, the doctor should be informed.

If the diagnosis is confirmed, then the next person the patient is referred to is an oncologist. After the examination, therapy, diet and prognosis for recovery are prescribed.

Diagnosis of lymphoma

Most patients see a doctor because they have certain signs of illness or feel unwell. Specialists begin the examination with an examination and questioning about family diagnoses, possible risk factors and other health problems. Then the lymph nodes and other parts of the body that contain lymphatic tissue are examined, including the spleen and liver. After which a number of studies are prescribed:

- Blood tests

: measure the levels of various cells in the blood, detect bone marrow damage, evaluate kidney and liver function, and detect infections and other problems. - Biopsy

is the removal of a piece of suspicious tissue and its transfer to a laboratory for examination. Depending on the course of the disease, doctors may need to biopsy lymph nodes, bone marrow, cerebrospinal fluid, pleural fluid, which is found in the chest, or peritoneal fluid, which is found in the abdomen. - Computed tomography, CT

- allows you to identify foci of the disease in the abdominal cavity, pelvis, chest, head and neck. - Magnetic

resonance

imaging, MRI

, creates a detailed image of soft tissue. The method is usually used to study the spinal cord or brain. - X-ray

– helps detect enlarged lymph nodes in the chest or bones. - Ultrasound, ultrasound

- used to study enlarged lymph nodes or various organs, such as the liver, spleen or kidneys. - Positron

emission

tomography, PET

, can detect lymphomas in enlarged lymph nodes, even those that appear normal on CT. In addition, it can be used to determine whether the disease is treatable.

In the oncology department, a complete diagnosis of lymphoma is carried out - quickly, without queues and loss of precious time, using the most modern equipment. Our specialists guide the patient “from” to “to” – from examination to any treatment.

Primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma of the skin

Primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma of the skin (mycosis fungoides) is the most common form of primary cutaneous lymphoma, caused by the proliferation of small to medium-sized lymphoid T cells with the presence of cerebriform nuclei and accompanied by the gradual evolution of spots and papules (plaques) into nodes. Most often occurs in people aged 50–60 years; men get sick twice as often as women. Currently, the clonal theory of the development of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma is generally accepted. Oncogenic mutations and the appearance of a clone of malignant lymphocytes are most often etiologically associated with retroviruses. This is supported by the positive results of isolating human T-lymphotropic virus type I (HTLV-1) in patients with mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome, as well as the detection of antibodies to this virus in such patients. A characteristic feature of the transcription of human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) is their individual variability and overexpression in tumor diseases. At the same time, the development of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma can occur under the influence of other reasons: hazards of industrial production, especially chemical and construction; agricultural hazards, medicines (antihistamines, hypotensives, antidepressants, tar, etc.); ionizing radiation; insolation; ultraviolet irradiation. The predisposing background for the development of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma can be chronic dermatoses - atopic dermatitis, chronic acrodermatitis atrophicus, psoriasis, etc. However, under the influence of various mutagenic factors, the emergence of a clone of malignant lymphocytes and, consequently, the occurrence of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma of the skin is determined, ultimately, at the genetic level. The typical pathogenetic mechanism of this disease is chromosomal instability. Nosological types of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma and the features of their clinical manifestations depend mainly on the tumor progression of the disease. Tumor progression is the main component of the pathogenesis of skin lymphomas. It, in turn, is determined by the degree of their differentiation and the pathology of mitoses [1–5].

Classic primary cutaneous epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) is characterized by heterogeneity of clinical subtypes and disease variants [2].

Bullous primary epidermotropic CTLC occurs in elderly people and is characterized by isolated or generalized blisters (subcorneal, intraepidermal, subepidermal) located on normal or hyperemic skin of the trunk and/or extremities. With it, acanthosis and a positive Nikolsky sign are sometimes observed, but only without the immunofluorescent phenomena characteristic of pemphigus. The appearance of bullous elements is considered a poor prognostic sign: within a year, in almost 50% of patients, the disease ends in death.

Hyperpigmented primary epidermotropic CTLC is most often observed in young people with dark skin and manifests as asymptomatic or itchy, non-scaling patches with ill-defined borders, plaques or nodules. Differential diagnosis is carried out with pityriasis versicolor, pityriasis alba, vitiligo, leprosy, sarcoidosis, post-inflammatory hypopigmentation. Tumor cells often have a CD8+ phenotype.

Poikilodermic primary epidermotropic CTCL is characterized by the presence, along with the typical manifestations of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma, of areas of atrophic vascular poikiloderma, represented by hyper- and hypopigmentation, dryness, skin atrophy, and telangiectasia. Poikiloderma often develops at the site of previous spots in areas of prolonged friction of the skin with clothing and can be limited or widespread. Differential diagnosis is made with the hyperpigmented type of primary epidermotropic CTCL.

Pigmented purpuric-like primary epidermotropic CTCL is characterized by diffuse patchy hyperpigmentation not associated with “atrophic vascular poikiloderma” and regression of previous elements. The phenotype of most tumor cells is CD4+; CD8+ are reactive. In some cases, rearrangement of clonal T-cell receptor (TCR) genes is noted. Epidermal changes are varied, but spongiosis and necrosis of keratinocytes are not observed. Therefore, this type of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma can only be distinguished from benign purpura pigmentosa by careful follow-up.

Primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma “without elements” is characterized by the presence of a single lesion involving less than 5% of the skin surface. Typically, the same areas of skin are affected as in the classic version of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma (breasts, armpits, buttocks).

Primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma of the palms and soles is observed in 11.5% of cases of the disease, manifested by specific changes in the form of ring-shaped hyperpigmented spots, plaques, hyperkeratosis, vesicular, pustular, dyshidrotic elements, verrucous formations, psoriasiform plaques, ulcerations, as well as nail dystrophy . The rash is limited to the palms and soles or may spread to the entire foot, hand, and fingers. Unless these lesions are associated with typical manifestations of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma elsewhere on the skin, the clinical diagnosis is difficult and is made histologically or by detecting clonal TCR gene rearrangements. Differential diagnosis includes fungal infections, dyshidrotic eczema, contact dermatitis, psoriasis of the palms and soles, warts, hypertrophic form of lichen planus, granuloma annulare. The course of this type of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma is usually indolent. Most often, skin lesions do not spread beyond the original sites, but even when the rash spreads to the extremities and trunk, extracutaneous lesions have not been described.

Hyperkeratotic/verrucous primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma manifests itself with hyperkeratotic and verrucous plaques, often against the background of manifestations of the classic variant of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma. The rash resembles manifestations of acanthosis nigricans or seborrheic keratosis and is most often located on the flexor surfaces (armpits, groin areas), neck, nipple and areola of the breast.

Ichthyosiform primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma is a rare type, occurring in 1.8% of cases. Clinically, the disease manifests itself as widespread ichthyosiform elements, often combined with comedo-like formations and/or follicular keratotic papules. Ichthyosiform elements are usually located on the extremities, although they can affect the entire surface of the body and are accompanied by itching and excoriation.

Pustular primary epidermotropic CTLC manifests as pustules located on the palms and soles. In addition, primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma may present with rashes resembling lichenoid keratosis chronicus, lichenoid parapsoriasis, or perioral dermatitis. In very rare cases, primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma has an extracutaneous localization, affecting the mucous membrane of the mouth and tongue, the conjunctiva of the eyes, and the mammary gland (in case of large cell transformation with spread to internal organs, we can speak of an extracutaneous variant of primary epidermotropic CTCL). The prognosis for the extracutaneous variant of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma is poor. For example, with primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma of the tongue (the frequency of which in the structure of the disease does not exceed 1%), death is observed up to 3 years after the lesion of the oral cavity. In advanced stages of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma, extracutaneous spread occurs along with damage to internal organs.

The main working classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas is the classification of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). The WHO/EORTC classification specifically identifies the following variants of primary epidermotropic CTCL [2, 6].

Folliculotropic is a rare variant of primary epidermotropic CTCL, occurring mainly in adults. Clinically, the folliculotropic variant of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma is manifested by intensely itchy grouped follicular or acneiform papules, compacted plaques (primarily in the eyebrows), nodes (usually on the head and neck), and sometimes alopecia (scalp, eyebrows). Phenotypically characterized by CD4+. The PCR method detects clonal rearrangements of genes encoding the TCR b- or γ-chain. Differential diagnosis is made with seborrheic and atopic dermatitis. The prognosis due to transformation to large cell lymphoma is worse than that of the classic form of primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma.

Pagetoid reticulosis is a variant of primary epidermotropic CTCL. The classic clinical variety of pagetoid reticulosis with limited manifestations (Woringer-Kolopp type) is characterized by the development of well-demarcated, slightly infiltrated plaques of round, oval, or irregular shape, the color of which varies from red to red-brown or red-violet. Plaques are localized on the skin of the distal extremities. Their surface is smooth, shiny with slight peeling in some areas, sometimes hyperkeratotic and warty in places. The lesions are characterized by slow peripheral growth with simultaneous central resolution and the formation of atrophy and hyperpigmentation. The edges of the lesions formed in this way have a ring-shaped or arcuate configuration, they can rise above the skin level, but, unlike basal cell carcinoma, they do not have an elevated ridge. Sometimes there is a mesh on the surface of the plaque, resembling a Wackham mesh. Men register twice as often as women. With the Vohringer-Colopp variety, internal organs are not affected. The disease occurs with damage to internal organs and often leads to death. The disseminated variety (Kettron–Goodman type), formerly also classified as pagetoid reticulosis, is now classified depending on its phenotype as aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ lymphoma or γ/8+ T-cell lymphoma. The phenotype of tumor cells is CD3+, CD4+, CD5+, CD8–; cases with the CD8+ phenotype have been described. Tumor cells can also express CD30. Molecular genetic research demonstrates clonal rearrangement of TCR β- or γ-chain genes. Differential diagnosis of the localized form of pagetoid reticulosis is carried out with Bowen's disease, psoriasis, and extramammary Paget's disease. Disseminated pagetoid reticulosis is clinically similar to classic primary cutaneous epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma; differentiation is carried out on the basis of clinical and morphological data. The course is long-term with the slow development of lesions, sometimes with their spontaneous regression. Consequently, the prognosis for life with a localized variant is relatively favorable, although dissemination is possible even after many years of relatively calm course of the localized process. In case of dissemination of the pathological process, damage to internal organs and death are possible.

Granulomatous flaccid skin syndrome is an extremely rare variant of primary epidermotropic CTCL that most often affects males. Clinically characterized by the presence of folded, infiltrated and non-elastic formations in large folds. The immunophenotype of tumor cells in the limited form is identical to that in classical primary epidermotropic CTCL. In rare cases, tumor cells express CD30 antigen. Giant cells express the histiocytic markers CD68 and CD163. Molecular biological studies reveal rearrangement of TCR genes. The clinical course is indolent in most cases.

Sezary syndrome is a form of CTCL in which leukemia occurs almost immediately. The first manifestation of the disease is exfoliative erythroderma with lymphadenopathy and only occasionally spots, plaques or tumors. The diagnosis is confirmed if more than 5% of atypical lymphocytes (Sezary cells) are present in the peripheral blood. It is identical in immunophenotype and genotype to primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma. Rearrangement of T cell receptor genes is found in tumor T cells in peripheral blood and lymph nodes. Transformation to a more aggressive large cell lymphoma can occur both in the skin, clinically manifested by ulcerated nodes, and in the lymph nodes even after resolution of erythroderma [2].

The international classification of primary epidermotropic CTCL by TNM and stages includes the following stages [7]:

- Stage IA - T1 (spots, papules or plaques occupying <10% of the body surface), N0 (peripheral lymph nodes are not enlarged, their histological examination shows no evidence of CTCL), M0 (internal organs are not affected);

- Stage IB - T2 (spots, papules or plaques occupying > 10% of the body surface), N0, M0;

- Stage IIA - T1–2, N1 (peripheral lymph nodes are enlarged, there is no evidence of CTCL in their histological examination), M0;

- stage IIB - T3 (one or more tumor-like formations on the skin), N0–1, M0;

- Stage III - T4 (erythroderma), N0–1, M0;

- Stage IVA - T1–4, N2 (lymph nodes are not enlarged, their histological examination shows evidence of CTCL) or N3 (lymph nodes are enlarged, their histological examination shows evidence of CTCL), M0;

- Stage IVB - T1–4, N0–3, M1 (internal organs are affected, their histological examination shows evidence of CTCL).

In the classical form, three stages of primary epidermotropic CTCL are clinically distinguished. Staging should include a thorough physical examination, a clinical blood test with formula calculation, a detailed biochemical analysis, the use of radiation methods, as well as a biopsy and bone marrow puncture if necessary.

Stage I (erythematous) is manifested by single or multiple red spots, subject to peeling with pityriasis, small and large lamellar scales. The intensity of peeling varies greatly: from mild to psoriasiform. In the latter case, there is a similarity with psoriasis. Against the background of spots, especially large ones, islands of healthy skin sometimes remain, which has a certain diagnostic value. Swelling may develop in the spots with the possible formation of bubbles on their surface. The bubbles, when opened, form erosions, and when they dry out, they form crusts. As a result, erythematous spots take on an eczema-like appearance. At the beginning of the disease, the spots are few in number, over time their number increases, and they spread over the skin with a predominant localization on the buttocks, torso and face. Often generalized spots, merging with each other, affect all or almost all of the skin (Fig. 1). Rashes of primary epidermotropic CTLC in stage I, especially in the early stages, are prone to spontaneous regression with subsequent relapses, and relapses in the same patient can clinically mimic different dermatoses. This clinical symptom complex indicates the reactive (dermotropic) nature of the damage to the lymph nodes. The duration of the erythematous stage varies: from several months to tens of years, usually 4–5 years. Remissions are possible, sometimes very long [1, 8].

Stage II (plaque) develops with the transition from the erythematous stage to the plaque stage imperceptibly and usually for a long time. Plaques arise either as a result of infiltration of erythematous spots, or on apparently healthy skin, are easily demarcated, have round or often irregular outlines, a flat or convex shape and a dark red, brownish or bluish-purple color. The surface of the plaques, dry and rough to the touch, is devoid of hair, including vellus hair, and is covered with scales, sometimes in large numbers. Upon palpation, a very dense consistency is determined (Fig. 2). Often plaques undergo spontaneous regression, leaving behind hyperpigmentation or, conversely, depigmentation, as well as mild atrophy. Only the center of the plaques can undergo regression. Plaques in these cases take on ring-shaped and semi-lunar shapes, and their spread and fusion leads to the formation of garland-like figures (Fig. 3 (A)). Over time, plaques, as a result of peripheral growth and fusion with each other, form extensive lesions, against which islands of healthy skin remain. The skin in the area of such lesions is thickened, unyielding, and can only be folded with difficulty; Dermographism here is usually white. They are very similar to foci of atopic dermatitis, especially when localized on the flexor surface of the limbs. The subcutaneous lymph nodes are changed, as in stage I, according to the reactive (dermatropic) type [1, 8].

Stage III (tumor) is characterized by the appearance of tumor lesions. Tumors develop from previous plaques or on apparently unchanged skin, protrude sharply above the skin as flat, hemispherical or dome-shaped formations, deep red, bluish-red or purplish-bluish in color with a diameter of 1–2 cm to 4–5 cm. Larger ones are also possible tumors with a diameter of up to 10–15 cm and even 20 cm. The tumors are dense to the touch. At first, their smooth surface is covered with scales, then undergoes maceration, erosion and ulceration. The surface of eroded tumors has the appearance of a deep red abrasion. Ulcers can be extensive and deep, often penetrating into the fascia, muscles and even bones. The bottom of ulcerative defects can be covered with purulent-bloody and necrotic plaque or brownish-black crusts (Fig. 3 (B-D)). Such ulcerative lesions emit a foul odor. In approximately every fifth patient, tumors transform into large cell sarcoma. The localization of tumors can be different; often, in addition to the torso and limbs, the face and scalp are affected. Facial lesions can occur according to the Facies leonina type. In addition to tumors, on the skin of patients there are erythematous and plaque rashes, typical of stages I and II of the disease, which gives the affected skin a mottled appearance; itching in the tumor stage can be alleviated. The course of the disease usually does not exceed 2–3 years. The tumor process in approximately half of patients extends beyond the skin, affecting lymph nodes, internal organs and bone marrow [1, 8].

The transformation of primary epidermotropic CTCL into anaplastic large cell lymphoma is determined by morphological features: more than 25% of large cells or focal growth of large cells. In primary epidermotropic CTLC, an increased level of intradermal CD30+ cells (more than 4.7%), the index of proliferative activity Ki-67+ (more than 14% of positive intradermal lymphoid cells) are unfavorable prognostic factors [2]. The typical immunophenotype of tumor cells is CD2+, CD3+, CD4+, CD5+, CD45 RO+, TCRB+ (clone bF1). Aberrant expression of pan-T-cell antigens is characteristic: less than 50% of CD2-positive, CD3-positive and/or CD5-positive cells compared to CD4-positive cells; Loss of CD7 antigen is common (<10% positive cells). Attention should be paid to the discordant expression of linearly limited T-cell antigens—CD2, CD3, CD5—by epidermal and dermal cells. In primary epidermotropic CTCL, CD4+ tumor cells do not express cytotoxic proteins. Expression of cytolytic proteins is possible with disease progression or in those rare cases of primary epidermotropic CTCL in which the tumor population is represented by CD8+ lymphoid cells with cytotoxic properties. In primary epidermotropic CTCL, a population of cytotoxic CD8+ lymphocytes is present to varying degrees of severity. In terms of differential diagnosis with actinic reticuloid, it is important to keep in mind that the predominant cells in chronic photodermatitis are polyclonal CD8+ lymphocytes [9–11].

In some cases, the first manifestation of primary epidermotropic CTCL is exfoliative erythroderma. It can occur again or develop as a result of progression of previous elements of T-cell lymphoma. The skin is diffusely bright red (sometimes with symmetrical unaffected islands) and peels off. Characterized by itching, increased body temperature, weakness, weight loss, lymphadenopathy, alopecia, ectropion, onychodystrophy. The histological picture does not differ from that of the classic variant of primary epidermotropic CTCL. The diagnosis is established on the basis of a complex of clinical, morphological, immunophenotypic and molecular genetic studies aimed at identifying clonal rearrangements of TCR γ-, β-chain genes [2, 9].

Primary epidermotropic CTCL has a benign course over several years or decades, slowly progressing to high-grade lymphoma. After the onset of the tumor stage, the life expectancy of patients does not exceed 3 years [9]. In the early stages, changes in the lymph nodes are reactive and correspond to dermatopathic lymphadenitis, in the later stages they are characterized by a specific lesion; The process may also involve internal organs, blood, and bone marrow.

In case of primary epidermotropic CTCL, accompanied by pathological changes in the general blood count (leukocyte-lymphocyte cell populations), a bone marrow examination is necessary. If lymph nodes are palpable, their histological examination is carried out. To assess the condition of the mediastinal, retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes, especially in stages T3 and T4 (according to the TNM classification), radiography or computed tomography of the chest and/or abdominal and pelvic cavity is performed.

Diagnosis of lymphoproliferative skin diseases is one of the most difficult problems in dermato-oncology. In most cases, only a comprehensive examination, including histological, immunohistochemical, cytogenetic and molecular biological research methods in combination with the analysis of clinical data, makes it possible to establish the correct diagnosis. The use of immunohistochemical study of cells of the lymphoid infiltrate and genotyping of lymphocytes increases the possibility of diagnosing malignant skin lymphomas to 80–90% [9]. An objective standardized clinical indicator of the severity of CTCL is the severity index (SI) of CTCL, which is calculated by summing up scores that assess the degree of involvement of the skin, lymph nodes, peripheral blood and internal organs in the pathological process (Table).

The index also allows predicting 5-year patient survival. To calculate the CTCL severity index, the sum of scores in all categories is calculated. Index values range from 0 to 75 points. Probable survival (%) is calculated using the formula:

124 – 2 × IT TCLK

The similarity of the early manifestations of CTCL with other numerous dermatoses makes timely diagnosis of the disease very difficult. The possibility of diagnosing skin lymphomas using clinical methods alone does not exceed 50%, and the use of cytomorphological and histological methods in the dynamics of the disease, with sufficient qualifications of the pathologist, increases the reliability of diagnosis to 75%. A number of authors highlight the clinical features and course of primary epidermotropic CTCL, which allow for a more reliable differential diagnosis, taking into account the similarity of the initial manifestations of primary epidermotropic CTCL with many benign dermatoses and the high frequency of diagnostic errors, which include: the development of the disease in old and senile age in the absence of indications in the anamnesis for previously established chronic dermatosis (constant intense itching of the skin, not related to the time of day, type of diet and not eliminated by taking antihistamines); paresthesia and chills before the appearance of fresh rashes; localization of lesions in places that are not typical for the diseases that they clinically imitate (psoriasis, eczema, neurodermatitis, etc.); stagnant bluish color of the lesions; variability of initial clinical manifestations, which leads to frequent changes in diagnosis throughout the entire period of the disease; lack of a lasting positive effect from commonly administered anti-inflammatory and hyposensitizing therapy; an increase in infiltration in the lesions as the disease progresses [2, 12]. Foreign authors [13] adhere to the following diagnostic criteria for the clinical diagnosis of early primary epidermotropic CTCL: progressive or persistent spots/plaques; damage to areas of the skin inaccessible to ultraviolet irradiation; variation in size/shape of lesions; presence of poikiloderma.

Histological examination in the early stages of primary epidermotropic CTLC, which is mandatory, does not always clarify the diagnosis, since at this stage of the disease the cellular infiltrate has not yet had time to form, and the number of atypical lymphocytes in the cellular composition of the dermis is extremely small and the inflammatory component of the morphological picture prevails over the proliferative one. A number of authors in the histological diagnosis of CTCL consider the following change in the epidermis to be significant: in its early stages, cells penetrating the epidermis have a higher proliferative activity than lymphocytes in the dermal proliferation. This confirms the important role of lymphoepidermal interaction in the pathogenesis of skin lymphomas [2, 9, 12]. The histological picture of CTCL is most striking at the late, tumor stage of the disease, when a pronounced infiltrate is formed and its cellular composition is dominated by a pool of atypical cells.

Rational therapy for primary epidermotropic CTCL should be developed not only taking into account clinical and morphological parameters, in accordance with the stage of the pathological process, but also taking into account the toxicity of the drugs used in the slow course of the disease in the early stages.

For primary epidermotropic CTCL in stage Ia (the process is limited to the skin (T1, N0) with <10% of the skin affected), the following are used: local corticosteroids; UVB phototherapy; systemic glucocorticoid hormones, with preference for prednisolone. The initial daily dose of 60 mg (12 tablets) is maintained until regression of clinical manifestations or significant improvement. Subsequent reduction of the daily dose is carried out by 5 mg (1 tablet) per week to 20 mg (4 tablets) per day. Prednisolone is taken at this dose for 4 weeks. Then continue its reduction by 2.5–5 mg per week until complete withdrawal. As a rule, long-term remission occurs, especially when treated with prednisone for at least 6 months. In stage Ib (the process is limited to the skin (T2, N0) with damage to > 10% of the skin), the following are used: UV-B phototherapy; PUVA therapy; Re-PUVA therapy; PUVA therapy with interferon-α; local irradiation of the skin with an electron beam; local radiation therapy of individual elements. In stage II and in primary epidermotropic CTCL with dermatopathic lymphadenopathy (T1–3, N0–1), the same treatment is prescribed as in stage Ib. In stage III and in primary epidermotropic CTCL with lymph node involvement (T1–4, N2), the following is performed: systemic (poly-) chemotherapy; local radiation therapy of tumors. In stage IV and primary epidermotropic CTCL with damage to internal organs (T1–4, N2 b, M1), the same treatment is carried out as in stage III [2, 11, 14].

When the process is generalized, as well as in primary epidermotropic CTLC of a high degree of malignancy, regardless of stage, the main method of treatment is polychemotherapy using the CAVP regimen (on the first day - intravenous cyclophosphamide, 750 mg/m2, adriamycin, 50 mg/m2, vincristine, 1.4 mg/m2, and on days 1–5 - prednisolone, 40 mg/m2 orally). The regimen consists of 6–8 cycles, which are carried out every 4 weeks under blood control; its effectiveness is 45% [2].

For ichthyosiform primary epidermotropic T-cell lymphoma, systemic retinoid therapy in combination with PUVA or UV-A therapy is effective. The folliculotropic variant of primary epidermotropic CTLC, due to the deep location of dermal infiltrates, is less sensitive to local therapy, radiotherapy and PUVA therapy, and therefore it is recommended to take oral sulfones, glucocorticoids (including in combination with cytostatics), injections with hydrocortisone, systemic use of interferon -α, skin irradiation with an electron beam. For pagetoid reticulosis, treatment is surgical: excision, intralesional injections of corticosteroid hormones, PUVA therapy, radiation therapy. For granulomatous “flabby” skin syndrome, radiation therapy and strong local glucocorticoids are used. The elements often recur after surgical removal. The first-line treatment for Sézary syndrome is extracorporeal photochemotherapy, the effectiveness of which reaches 73% with complete remission in 21% of cases. In addition, fast electron therapy is carried out. When transforming into aggressive large cell lymphoma - polychemotherapy. Treatment methods for the tumor stage of primary epidermotropic CTCL remain unsatisfactory. The disease progresses rapidly despite the use of polychemotherapy [1, 2, 8]. According to Beyer M. et al. the combination of bexarotene and vorinostat is a promising strategy for increasing the effectiveness of treatment of primary epidermotropic CTCL and reducing the incidence of side effects [15].

Thus, the problem of primary T-cell cutaneous lymphomas is one of the most important and priority problems of modern medicine, both due to their high prevalence and the extreme complexity of diagnosis and treatment, requiring consideration of many factors and the use of a wide range of modern examination methods (histological, immunological , molecular genetic), allowing to correctly determine the prognosis and optimize therapy.

Literature

- Potekaev N. S. Mycosis fungoides. Clinical dermatovenerology. A guide for doctors, ed. Yu. K. Skripkmna, Yu. S. Butova. M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2009. T. 2. P. 576–589

- Molochkov A.V., Kovrigina A.M., Kildyushevsky A.V. et al. Lymphoma of the skin. Publishing house BINOM, 2012. 184 p.

- Petrenko E.V. Improving the early diagnosis of T-cell lymphomas of the skin based on assessing the expression of TsPO (peripheral benzodiazepine receptor) as a marker of the intensity of tumor cell proliferation: Abstract of thesis. diss. ...cand. honey. Sci. M., 2011. 23 p.

- Podtsubnaya I. V. Non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Clinical oncohematology. Under. ed. M. A. Volkova. M.: Medicine, 2001. P. 336.

- Pilvi Maliniemi, Michelle Vincendeau, Jens Mayer, Oliver Frank et al. Human endogenous retrovirus type w envelope expression in mycosis fungoides provides new Insights in cutaneous T-cell lymphomas. EORTC CLTF 2012. Targets for therapy in cutaneous lymphomas. 2012. R. 27.

- Willemze R., Jaffe ES, Durg G. et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas // Blood. 2005. Vol. 105, No. 10. P. 3768–3785.

- Clinical recommendations. Dermatovenerology. Ed. A. A. Kubanova. M.: DEX-Press, 2010. 428 p.

- Korotkiy N. G., Udzhukhu M. V. Modern views on the etiopathogenesis of mycosis fungoides and its treatment regimens // Treating Doctor. 2007. No. 4. pp. 35–37.

- Molochkov V. A., Kovrigina A. M., Ovsyannikova G. V. T-cell lymphomas of the skin: modern approaches to clinical and morphological diagnosis (according to the WHO/EORTC classification) and treatment // Ross. magazine leather veins diseases. 2009. No. 3. P. 4–9.

- Potekaev N. N. Reactive dermatoses // Clinical dermatology and venereology. 2010. No. 1. pp. 83–86.

- Doronin V. A. Diagnosis and treatment of primary T-cell lymphomas of the skin // Treating Physician. 2005. No. 7. pp. 15–19.

- Ovsyannikova G.V., Lezvinskaya E.M. Malignant lymphomas of the skin. Consilium Medicum. 2005. T. 7. No. 1. P. 21–23

- Rook A., Wysocka M. Cytokines and other biological agents as immunotherapeutics for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma // Adv. Dermatol. 2002; 18; 29–43.

- Kim EJ, Hess S, Richardson SK et al. Immunopathogenesis and therapy of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma // J. Clin. Inv. 2005. Vol. 115, No. 5. R. 798–812.

- Beyer M., Humme D., Sterry W. Current status of combination therapies in Mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome. EORTC CLTF 2012. Targets for therapy in cutaneous lymphomas, 2012. R. 23.

L. A. Yusupova1, Doctor of Medical Sciences Z. Sh. Garayeva, Candidate of Medical Sciences E. I. Yunusova, Candidate of Medical Sciences G. I. Mavlyutova, Candidate of Medical Sciences

GBOU DPO KSMA Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Kazan

1 Contact information

Lymphoma stages

Immediately after detecting the disease, doctors determine its stage - find out how far it has spread and what tissues it has damaged. This information is extremely important for specialists, since it allows not only to understand the patient’s prognosis, but also to select the most appropriate treatment for him.

Stages of Hodgkin lymphoma:

I

: Changed cells are found in only one group of lymph nodes or one lymphoid organ, such as the tonsils.

II

: they are present in 2 or more groups of lymph nodes located on one side of the diaphragm, or have spread from one damaged lymph node to an adjacent organ.

III

: lymphoma cells are present in the lymph nodes on both sides of the diaphragm;

or not only in the lymph nodes above the diaphragm, but also in the spleen. IV

: The disease has spread to at least one organ outside the lymphatic system, such as the liver, bone marrow, or lungs.

Stages of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas:

I

: altered cells are found only in 1 group of lymph nodes or one lymphoid organ, for example, tonsils;

or in 1 area of one organ outside the lymphatic system. II

: they are present in 2 or more groups of lymph nodes on 1 side of the diaphragm;

either in the lymph nodes and 1 area of an adjacent organ, or in another group of lymph nodes on the same side of the diaphragm. III

: lymphoma cells are present in the lymph nodes on both sides of the diaphragm;

or they are present in both the lymph nodes above the diaphragm and the spleen. IV

: The disease has spread to at least one organ outside the lymphatic system, such as the liver, bone marrow, or lungs.

Determination of the stage (extent of spread) of non-Hodgkin lymphomas

After a detailed examination, including all of the above methods, the stage of lymphoma is specified (from I to IV) depending on the degree of spread of the tumor process.

If the patient has general symptoms, the symbol B (or the Latin letter B) is added to the stage, and if they are absent, the symbol A is added.

To predict the rate of tumor growth and the effectiveness of treatment, an international prognostic index (IPI) has been developed, which takes into account 5 factors, including the patient’s age, stage of the disease, damage not only to the lymph nodes, but also to other organs, the general condition of the patient, and the level of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in the serum blood.

Favorable prognostic factors include: age less than 60 years, stages I-II, absence of organ damage, good general condition, normal LDH levels.

Unfavorable prognostic factors include: patient age over 60 years, stages III and IV, damage to lymph nodes and organs, poor general condition and increased LDH levels.

Lymphoma treatment

Treating lymphoma is not an easy task.

To solve it, you need not just one doctor, but a whole team of professionals - a chemotherapist, radiologist, surgeon, oncologist, hematologist and others. The oncology department has all the necessary specialists - world-class doctors who conduct a full diagnosis of the disease and any necessary therapy. With us, you don’t have to retake tests, redo studies and ask the question “what to do next?”

We fully guide the patient and give him a clear action plan, following which he gets the best possible result. Several methods are used to combat this type of cancer:

The main one is chemotherapy

– drugs that destroy altered cells. They are taken in pill form or injected into a vein, enter the bloodstream and spread throughout the body. Treatment is carried out in cycles, each lasting several weeks, followed by a period of rest during which the body recovers.

Bone marrow transplantation

or stem cells from which blood cells are formed. The procedure allows higher doses of chemotherapy, sometimes along with radiation, to be given, which helps kill the lymphoma more effectively. Transplantation is possible not only with donor material, but also with your own material, collected several weeks before the intervention.

Radiation therapy

– destruction of altered cells using radiation. This method is suitable for most patients, and works especially well if the disease has affected a small amount of tissue. It is used both independently and in combination with chemotherapy.

Immunotherapy

– drugs that help a person’s own immune system better recognize and destroy abnormal cells. There are several types used for lymphomas. These include:

- monoclonal antibodies are proteins designed to attack a specific substance on the surface of lymphocytes;

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors - drugs that prevent altered cells from masquerading as healthy ones;

- T-cell therapy: removal of immune cells from the patient’s blood and modification in the laboratory, their reproduction and return to the body, where they find and destroy foci of the disease.

Surgery

: Often used to obtain samples of suspicious tissue and determine its type, but rarely for therapy itself. In rare cases, operations are prescribed for lesions of the spleen or other organs that are not part of the lymphatic system - for example, the thyroid gland or stomach.

Types of lymphomas by aggressiveness

Since there are many diseases that are included in this group, they are usually divided into groups according to different criteria. One of them is the aggressiveness of the current.

So-called flaccid lymphomas (also known as indolent lymphomas) develop slowly and do not threaten the patient’s life for several years. With timely treatment, the chances of a long and lasting remission are high. This group includes lymphocytic as well as follicular lymphoma.

Aggressive forms, which include diffuse (mixed and large cell) forms, can kill the body within months, and highly aggressive forms - even within weeks. The latter, for example, include T-cell leukemia and Burkitt's lymphoma. In the treatment of any disease and in maintaining the adequate condition of the patient, timely professional assistance plays an important role.

Clinical observation for NHL

Dynamic observation of children and adolescents is carried out for at least 3 years after completion of the treatment program.

In the first 3 months, the patient is examined every month, in the next 9 months - every quarter, then every six months.

The examination includes an examination of the patient with an assessment of complaints, clinical and biochemical blood tests with determination of LDH, ultrasound of the primary lesion, chest X-ray, and CT/MRI is used if indicated.

In recent years, whole body PET/CT with glucose has become widespread for dynamic monitoring of cured patients for the purpose of early diagnosis of relapse.