Status epilepticus is a condition characterized by frequently recurring or continuous epileptic seizures lasting up to half an hour.

Moreover, each new seizure occurs earlier than the patient manages to recover from the previous one. During the time between attacks, consciousness remains unclear, and signs of coma persist, which are characterized by impaired blood flow through the vessels and respiratory dysfunction.

Epistatus is the most common neurological condition. The incidence of this pathology is approximately 20 cases per 100,000 people.

In half of the cases, ES occurs in young children. Among people suffering from epilepsy, this condition is more common in children than in adults (in a ratio of 15-25% to 5%).

About 7% of patients with epilepsy have a history of one to three epilepsy attacks throughout their illness.

What is the provoking factor?

{banner_banstat0}

The main reason for the occurrence of epileptic seizures is the withdrawal of medications taken, the action of which is aimed at suppressing epileptic seizures.

However, status epilepticus can occur not only against the background of epilepsy, but also due to brain lesions, including:

- head injury;

- intoxication;

- intracranial malignant tumor;

- circulatory disorders in the brain;

- infection;

- dropsy of the brain (encephalopathy);

- withdrawal syndrome;

- complications of diabetes;

- hematoma.

The incidence of epistatus without a predisposing factor - epilepsy is approximately 50%.

Causes of status epilepticus

The action of medications taken by a patient with epilepsy is aimed at inhibiting seizures. If the patient independently refuses medications prescribed for treatment, then this action can trigger the occurrence of ES.

Epistatus can also occur, for example, with brain pathologies:

- Malignant neoplasms;

- Withdrawal syndrome;

- Infections, intoxications, hematomas and encephalopathy;

- Peripheral circulation disorders.

Status epilepticus can also occur in patients with diabetes. Diabetes is scary because of its complications, including ES.

Types and stages of epistatus

{banner_banstat1}

The variability of the types of epileptic seizures determines the formation of various clinical forms of epileptic seizures. They are divided into two main groups - convulsive and non-convulsive seizures.

According to the classification, the following types of status epilepticus are distinguished:

- Generalized

SE - characterized by widespread tonic-clonic convulsions with an unconscious state. - Not completely generalized

ES - characterized by atypical muscle spasms with complete loss of consciousness. Tonic status is most common among children with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Can be observed at different ages. Clonic status is observed with epilepsy in infants, as well as with convulsions with high fever in young children. Myoclonic status is characterized by constant or episodic muscle twitching. - The status of focal paroxysms

proceeds according to the type of Jacksonian epilepsy with muscle contraction of a certain localization, for example, only the muscles of the face, one limb or half of the body. In this case, loss of consciousness may not occur. - Absence or non-convulsive status

is accompanied by a complete loss of consciousness without muscle contractions. Such attacks are characterized by the mildest course, however, due to the absence of seizures, diagnosis can be difficult. - Partial status

is characterized by unconscious and automatic actions with complete or incomplete loss of consciousness.

The stages of development of epistatus are also distinguished:

- pre-status

- lasts 1-10 minutes; - initial

- lasts from 10 minutes to half an hour; - expanded

- lasts from half an hour to an hour; - refractory

- lasts more than an hour.

Since the time of M. Bourneville [1], status epilepticus (SE) has traditionally been regarded as a severe life-threatening condition. For a long time, the definition of SE by L. Clarc and T. Proute [2] remained unshakable: status epilepticus - a condition in which attacks occur with such frequency that coma and exhaustion between attacks become permanent. Since E.S. traditionally considered as a convulsive state, it was divided into primary and secondary generalized, focal (partial) and unilateral, and according to the characteristics of convulsive manifestations into the status of tonic-clonic, tonic, clonic and myoclonic seizures. Further progress in the development of the problem of ES was associated with the development of basic sciences and the introduction of their results into clinical practice. The emergence and application in clinical practice of methods for recording electrical potentials of the brain—electroencephalography (EEG)—was fundamental. This made it possible to move on to the clinical and electrographic definition of epileptic seizures and expand the understanding of the manifestations of epileptic seizures.

Back in 1974, we [3] put forward a subsequently confirmed assumption that there are as many forms of SE as there are types of epileptic seizures. Moreover, non-convulsive forms of epileptic encephalopathy have been discovered, in which progressive neurological manifestations and mental disorders, often severe, are a consequence of persistent epileptiform activity. One of the most unusual forms is electrical ES of slow-wave sleep.

In the process of studying ES, the problem of its differential diagnosis arose with cases of depression of consciousness (stupor, coma) or psychosis, when paroxysmal, including epileptiform, phenomena, and sometimes mild convulsive manifestations (with stupor and coma) can be recorded on the EEG.

All of the above served as the basis for the serious work of the Commission on the classification of E.S. International League Against Epilepsy to develop a definition and modern classification of epilepsy [4], which we are considering here with some abbreviations.

In November 2015, the said commission proposed a new definition and classification of E.S. The following definition was formulated: SE is the result of either a failure of the mechanisms responsible for the cessation of seizures, or the initiation of mechanisms that lead to abnormally prolonged seizures - after 30 minutes (t1). This is a condition that can have long-term consequences (beyond t2), including damage and death of neurons, alteration of the nervous network, depending on the type and duration of seizures.

Note that it took the League more than 40 years to define ES according to a fundamentally different, namely qualitative criterion, which was proposed by us in a discussion at the European Congress on Epilepsy in Warsaw back in 1998, but, unfortunately, was preserved only in the Russian-language literature: “SE is a qualitatively different condition from an epileptic seizure, characterized by deep depression of the antiepileptic defense system: a) with the ability to only actively suppress each epileptic seizure, but not prevent the next one; b) subsequent total failure of the antiepileptic defense system with the cessation of each seizure only in a passive way, namely due to the depletion of energy resources [5].”

From the above definition of the League it is clear that it applies time criteria, namely 30 minutes. But this can hardly be considered successful, since it is necessary to start treatment for E.S. as early as possible. The League now quite reasonably proposes different time criteria for different seizures, providing a different time frame for each patient, depending primarily on the type of seizure he is experiencing. This is reflected in the corresponding time parameters.

It is proposed to classify ES using the following 4 blocks: 1. Semiology, 2. Etiology, 3. EEG correlates, 4. Age. Ideally, each patient should be considered in each of the 4 blocks. However, it should be kept in mind that as with other acute neurological conditions, the semiology (symptoms and signs) and EEG correlates of SE are very dynamic and can change over a short period of time. Thus, during repeated neurological examinations and repeated EEG recordings during ES, changes may occur that require a different interpretation than the initial one. For example, SE may begin with focal motor symptoms, including bilateral convulsive SE (A.1.b) and may manifest several hours later as non-convulsive SE (NES) with coma and minimal motor phenomena resembling so-called “mild status” (B. 1). In addition, periodic lateralized changes may initially appear on the EEG, and upon repeated examination, a bilateral synchronized type of electrical activity is detected. Nevertheless, let's look at each of the blocks.

Block 1:

Semiology

This block includes the clinical manifestations of ES that form the basis of the classification. The two main taxonomic criteria are: 1. The presence or absence of predominant motor symptoms; 2. The degree (qualitative and quantitative) of impairment of consciousness. Forms with a predominance of motor symptoms and impaired consciousness can be combined with the concept of convulsive E.S. Moreover, the term convulsive in this case is fundamental, reflecting the usual language of the doctor. In this regard, the fundamental term is the term “status epilepticus”. In the 19th century, in French medicine, the term “état de mal” corresponded to it. The generally accepted term “convulsive” in the context of SE refers to “episodes of excessive pathological muscle contractions, usually bilateral, which may be prolonged or intermittent.”

Block 1 also includes the classification of ES:

A. SE with predominance of motor symptoms

A.1. Convulsive E.S. (SES, synonym: tonic-clonic ES). A.1.a. Generalized convulsive. A.1.b. The focal onset progresses to bilateral convulsive ES. A.1.c. It is unknown whether it is focal or generalized.

A.2. Myoclonic E.S. (predominance of epileptic myoclonic twitches). A.2.a. With a coma. A.2.b. No coma.

A.3. Focal motor. A.3.a. Recurrent focal motor seizures (Jacksonian). A.3.b. Epilepsy partialis continua (ERS)1. A.3.c. Adversive status. A.3.d. Oculoclonic status2. A.3.e. Ictal paresis (i.e. focal inhibitory ES).

A.4. Tonic status.

A.5. Hyperkinetic E.S..

B. SE without predominance of motor symptoms

(i.e. non-convulsive ES, BES)

B.1. BES with coma (including the so-called “soft” ES).

B.2. BES without coma. B.2.a. Generalized. B.2.aa Typical absence status. B.2.ab Atypical absence status. B.2.ac Myoclonic absence status. B.2.b. Focal. B.2.ba Without disturbance of consciousness (aura continua, with vegetative, sensory, visual, olfactory, gustatory, emotional/mental/experiential or auditory symptoms). B.2.bb Aphasic status. B.2.bc With impaired consciousness. B.2.c. It is unknown whether it is focal or generalized. B.2.ca Vegetative E.S..

Block 2

: Etiology

The causes underlying SE are classified in accordance with the views of the commission of the International League Against Epilepsy dating back to 2010, but in this case, established terms are used that are used by epileptologists, emergency physicians, neurologists, pediatric neurologists, neurosurgeons, family doctors and other specialists dealing with patients with ES.

Currently undefined conditions (or "borderline syndromes")

Epileptic encephalopathy. Lateralized and generalized periodic discharges with a monotonous manifestation are not considered as involving EEG patterns. Behavioral disorders (eg, psychosis) in patients with epilepsy. Acute confusion (eg, delirium) with epileptiform EEG patterns.

The term "known" or "symptomatic" is used, according to general neurological terminology, to designate SE caused by a known disorder, which may be structural, metabolic, inflammatory, infectious, toxic or genetic. Based on their temporal relationships, a division into acute, delayed and progressive manifestations can be applied.

The term "idiopathic" or "genetic" does not apply to the underlying etiology of E.S. In idiopathic or genetic epileptic syndromes, the cause of the status is not the same as the disease itself, since certain metabolic, toxic or intrinsic factors (such as sleep deprivation) can cause epilepsy in these syndromes. Therefore, the term "idiopathic" or "genetic" is not used here. SE in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (which itself is “idiopathic” or “genetic”) may be symptomatic as a result of treatment with an inappropriate antiepileptic drug (AED), abrupt drug withdrawal, or drug toxicity.

The term "unknown" or "cryptogenic" (Greek κρύπτος, hidden or unknown, τò γένος, family, class, generation, descent) is used in its strictly original meaning: unknown cause. The suggestion that this is a "supposed" symptomatic or genetic cause is inappropriate. The term "unknown" or corresponding translations in different languages may be used synonymously and in accordance with the 2010 proposal.

Known (i.e. symptomatic). Acute (for example, stroke, intoxication, malaria, encephalitis, etc.). Remote (for example, post-traumatic, post-encephalitic, post-stroke, etc.). Progressive (for example, brain tumor, Lafora disease and other PME, dementia). ES in certain electroclinical syndromes. Unknown (i.e. cryptogenic) ES in its various forms has many causes. Attached to this section is a list that will be updated periodically.

Block 3

: Electrographic correlates

None of the EEG patterns of any type of ES are specific. Epileptiform discharges are considered a characteristic feature, but with increasing duration of SE, changes in the EEG and rhythmic non-epileptiform changes may predominate. Similar EEG patterns, such as triphasic waves, can be recorded in different pathological conditions, leading to considerable confusion in the literature. Despite the fact that the EEG is overloaded with motor and muscle artifacts and thus limits its clinical value, it is indispensable in the diagnosis of BES, since clinical signs (if any) are often blurred and nonspecific.

Currently, there are no specific EEG criteria for E.S. But based on the large amount of data existing in this area, we propose the following terminology to describe EEG patterns in SE: 1. Localization: generalized (including bilateral synchronous patterns), lateralized, independent bilateral, multifocal. 2. Pattern name: periodic discharges, rhythmic delta activity or spike-wave/sharp wave, and subtypes. 3. Morphology: acuity, number of phases (for example, three-phase morphology), absolute and relative amplitude, polarity. 4. Temporal characteristics: prevalence, frequency, duration, daily pattern and index duration, onset (sudden or gradual) and dynamics (evolving, fluctuating or constant). 5. Modulation: stimulus-induced or spontaneous. 6. Effect of intervention (medicines) on EEG.

Block 4: Age of patients

In this case, the following division of ages and their definition is used: 1. Newborn (from 0 to 30 days). 2. Infancy (from 1 month to 2 years). 3. Childhood (over 2 years old and up to 12 years old). 4. Adolescence and adulthood (over 12 years and up to 59 years). 5. Elderly (60 years and older).

ES in newborns can be blurred and difficult to recognize. Some forms of SE are considered an integral part of the electroclinical syndrome; others may occur in patients with a specific electroclinical syndrome, or when triggers or precipitating causes are present, such as sleep deprivation, poisoning, or inappropriate medications. Examples are the use of phenytoin for some forms of progressive myoclonic epilepsy, carbamazepine for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy or absence epilepsy.

Considering the age aspect of SE, it is necessary to note that it is correct to talk about the predominant manifestation of certain forms of SE in certain age groups, which can also occur in other age groups.

SE, which occurs in newborns and infancy, is the debut of epileptic syndromes. Tonic status (for example, Ohtahara syndrome or West syndrome). Myoclonic status in Dravet syndrome. Focal status. Febrile status.

ES, which occurs mainly in childhood and adolescence. Vegetative E.S. with early onset of benign childhood occipital epilepsy (Panayotopoulos syndrome). BES for specific childhood epileptic syndromes and etiologies (for example, ring 20 syndrome and other karyotypic disorders, Angelman syndrome, epilepsy with myoclonic-atonic seizures, other childhood myoclonic encephalopathies. Tonic status in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Myoclonic status in progressive myoclonic epilepsy. Electrical status epilepticus during slow-wave sleep (EES). Aphasic status in Landau-Kleffner syndrome.

ES, which occurs predominantly in adolescence and adulthood. Myoclonic status in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Absence status in juvenile absence epilepsy. Myoclonic status in Down syndrome.

ES, which occurs mainly in old age. Myoclonic status in Alzheimer's disease. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. De novo

(or recurrent) absence status in elderly and especially senile age.

Undoubtedly, the Commission of the International League Against Epilepsy has done a great job, including taking into account the dependence of the type of epileptic seizures and forms of epilepsy on age. It is important to note that the commission gave a fundamentally age-based classification of epilepsy, adapted for the diagnosis of epilepsy. The following considerations should be made as comments. The proposed classification has serious scientific significance and is the basis for further development of the problem. However, due to its bulkiness, it is not entirely convenient for use by a practicing physician. This requires a reservation and reference to a less detailed, but more convenient classification by E. Trinka et al. [6]. There are three appendices to the classification: 1) a list of neurological diseases in which ES can occur, grouped into 17 headings - about 115 items in total; 2) “a list of specific connections in which ES is an integral part of the syndrome, entity or symptom with strict clinical involvement (the list can be finalized)”: absence status in the syndrome of the 20th ring chromosome, Angelman syndrome and absence status of epilepsy3 .

Appendix 3 presents all previous definitions and classifications of ES. It would be advisable to indicate before Appendix 1 that ES can occur with any brain damage and therefore even the listing of 115 diseases cannot be exhaustive. Another necessary addition: ES in some cases can occur with extracerebral intoxication (1) as a de novo

.

Now about the definition of E.S. For a long time, the League tried to base the definition of ES on the time factor, proposing various time criteria - from 5 to 30 minutes, but this turned out to be unsuccessful. Now another criterion has been proposed: SE is a different qualitative state, characterized by insufficiency of the mechanisms responsible for the termination of an epileptic attack or the initiation of mechanisms that lead to an abnormally prolonged attack. And here is the definition of ES that we proposed in the discussion at the above-mentioned European Congress on Epilepsy in Warsaw (1998). This definition has been preserved, unfortunately, only in Russian-language literature [2]. We defined SE as a qualitatively different state from an epileptic attack, characterized by the following features: a) deep depression of the antiepileptic defense system, preserving the possibility of only actively suppressing each epileptic seizure, but not preventing the next one; b) total failure of the antiepileptic defense system with the cessation of each seizure only in a passive way, namely due to the depletion of energy resources. We also recently presented detailed data on the systemic mechanisms of antiepileptic defense in a lecture that was given in London at the 6th London-Innsbruck Colloquium on SE and acute epileptic seizures [7], to which there is also no reference.

As for the temporary criterion of SE, as indicated above, the League did not abandon it, but proposed differentiated criteria for the three main forms of SE: tonic-clonic, focal status with impaired consciousness and absence status. It is proposed to introduce two indicators: tT - the time during which seizures are likely to be prolonged to their constant activity and t2 - the time when seizures can cause long-term consequences (neuronal damage, neuronal death, damage to the neuronal network and functional deficit). This is a fundamentally new and very important approach to assessing ES and its possible consequences.

There is no reference to A.Ya. Kozhevnikova.

There is no synonym for "epileptic nystagmus".

Here is a link to the article by P. Gentone et al. “Absence status epilepsy: delineation of a distinct idiopathic generalized epilepsy syndrome.Epilepsia. 2008;49:642−649.

What does it look like in real life

{banner_banstat2}

Symptoms of status epilepticus are determined by severe disorders in consciousness, respiratory system and hemodynamics, which are caused by the previous attack; the number of seizures during epileptic status can range from 3 to 20 per hour.

Consciousness by the time of the next attack does not clear up and the person is in a state of stupor, numbness or coma.

With prolonged ES, the comatose state worsens, becomes deeper, convulsions take on a tonic form, an increase in blood pressure is replaced by a sharp decrease, and increased reflexion is replaced by a lack of reactions. Hemodynamic and respiratory disorders become more pronounced.

The convulsions may disappear, and then the stage of epileptic prostration begins, which is characterized by external changes:

- pupil size changes;

- the gaze becomes unconscious;

- mouth slightly open.

It is very dangerous!

In this condition, death can occur. Epistatus necessarily lasts more than half an hour. This condition should be differentiated from episodic attacks, during the intervals between which there is a complete or almost complete clearing of consciousness, as well as a partial restoration of the patient’s physiological state.

The course of convulsive SE can be divided into two phases. At the first stage, compensatory changes occur to maintain blood circulation and the metabolic process.

This condition is characterized by:

- tachycardia;

- high blood pressure;

- vomit;

- involuntary urination;

- involuntary defecation.

The second phase occurs after half an hour or an hour and is characterized by a breakdown of compensatory changes. In this state, the following processes occur:

- lowering blood pressure;

- arrhythmia;

- respiratory dysfunction;

- thrombosis of the pulmonary artery and its branches;

- acute renal and liver failure.

Non-convulsive epistatus is characterized by various disorders of consciousness:

- feeling of detachment;

- immobilization.

In the case of ES of complex partial seizures, the following is observed:

- behavioral deviations;

- confusion;

- symptoms of psychosis.

Status epilepticus from A to Z:

First aid - rules and tips

{banner_banstat3}

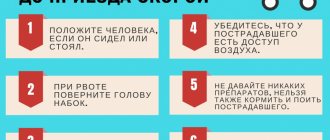

The main goal when providing first emergency aid in case of epistatus before the arrival of doctors is to prevent damage and traumatization of the patient.

What to do during an attack:

- lay the person on a comfortable surface to reduce the risk of injury;

- remove those items of clothing that may cause discomfort (for example, a tie, a belt), unbutton the collar;

- place rolled clothing under your head;

- carefully turn your head to the side so that the patient does not choke on his saliva;

- if your mouth is slightly open, you need to put a handkerchief or some kind of cloth between your teeth, but in no case a sharp object, so as not to break your teeth;

- remove all dangerous objects that are in the immediate vicinity to avoid injury;

- do not hold the person too tightly, otherwise there is a high risk of broken bones;

- do not open your teeth if they are clenched.

Introduction

Doctors of various specialties deal with status epilepticus: neurologists, epileptologists, neurosurgeons, psychiatrists, general anesthesiologists and resuscitators, neuroreanimatologists, psychoreanimatologists, sometimes even obstetricians and infectious disease specialists.

There is no clear attribution of this condition to any medical discipline. Most often, the question of who will treat such a patient is determined by random reasons (for example, distance to the nearest medical facility). In this brief guide, attention is focused on the treatment of those patients who come to the attention of psychoreanimatology. The material is based on twenty years of experience in the intensive care unit (Moscow Regional Center for Psychoreanimatology) at the Moscow Regional Psychiatric Hospital No. 23. According to this unit, patients with status epilepticus make up no more than 3% of the total flow of emergency patients admitted there, but the severity of their condition, requiring intense and dramatic work of staff, are in one of the first places. These recommendations do not constitute exhaustive rules to which there is nothing to add. Each patient can, with his or her individuality, force us to make adjustments to treatment. Each unit of psychoreanimatology has its own differences in traditions, approaches and equipment. Therefore, the material presented here is best used as a story from experienced people about what and in what sequence they usually do when treating epistatus - a story that should in no way hinder the creativity of a practicing doctor.

Further actions

{banner_banstat4}

Relief of status epilepticus is carried out through the following measures:

- ensuring airway patency;

- use of oxygen therapy;

- intravenous injection of Diazepam (maximum daily dose - 40 mg), a side effect of this drug may be respiratory depression.

Further therapy is carried out by administering medications depending on the stage of status epilepticus.

At the initial stage, the following drugs are used to relieve status epilepticus:

- Diazepam;

- Lorazepam;

- Depakine;

- Feniton;

- Oxybutyrate.

Among the side effects of treatment, the following consequences can be identified: arterial hypotension, acute toxic hepatitis, phlebosclerosis, hypokalemia.

At the advanced stage of ES the following is used:

- Diazepam;

- Lorazepam;

- Phenobarbital;

- Sodium thiopental.

At the refractory stage of ES, the following measures are carried out:

- Intubation, correction of electrolyte disturbances, transfer to artificial ventilation of the lungs

- to maintain vital functions of the body. - Barbiturate anesthesia

- intravenous injection of sodium thiopental for 20 seconds. 100-250 mg of the drug is administered. If the patient's condition does not improve, a dose of 50 mg is administered every few minutes until the seizure stops. Barbiturate anesthesia can last from 12 hours to a day. - Dexamethasone and Mannitol injections

are given to prevent cerebral edema. - Infusion dehydration therapy

is carried out to eliminate disorders of liquor dynamics and the metabolic process. For this purpose the following are used: Magenzia, Lasix, Cordiamin, Eufillin, Korglykon.

In the event that the epistatus is symptomatic, that is, it arose against the background of brain damage, a neurosurgical operation should be performed to compress the brain vessels.

Worth a try

There is evidence that lorazepam is more effective than diazepam in epistatus. A parenteral dosage form of valproic acid (Depakine) has appeared, specifically intended for the treatment of epistatus.

Work has been carried out indicating the prospects of using hemosorption in the treatment of severe forms of epistatus.

There are observations that intravenous laser irradiation of blood increases the effectiveness of other measures for epistatus.

There is evidence of the effectiveness of electroconvulsive therapy for intractable forms of epistatus.

Features of the condition in children

{banner_banstat5}

Very often, epistatus that occurs in children is a sign of the onset of epilepsy, however, it happens that convulsive seizures appear already in the later stages of the course of this disease.

In newborns, a seizure occurs with partial loss of consciousness, while the reaction to external stimuli remains intact.

Generalized SE can manifest itself as tonic-clonic, clonic, myoclonic convulsions.

In nonconvulsive SE, electroencephalography is used to detect peak-wave stupor and slow waves, which reflect a state of epileptic stupefaction. Partial ES can be simple, somatomotor, or dysphasic.

In complex partial epistatus, stable preservation of epileptic twilight of consciousness is observed.

With generalized SE, the main property of an epileptic seizure is disrupted - it does not go away on its own.

The number of attacks can reach several tens or even hundreds per day. In this case, respiratory function and hemodynamics are disrupted, metabolic processes in the brain are disrupted, and the coma state can deepen until death occurs.

Danger of condition

{banner_banstat6}

Mortality in the case of status epilepticus with previously diagnosed epilepsy is 5%, in the case of symptomatic status - 30-50%. If the ES continues for more than an hour, the following serious consequences may occur:

- cerebral edema;

- oxygen starvation of the brain;

- excessive decrease in blood pressure;

- lactic acidosis - excessive accumulation of lactic acid in the body;

- electrolyte imbalance;

- mental retardation and mental retardation in children.

Non-convulsive SE is less dangerous than generalized SE, however, in this case, cognitive impairment may develop.

Complications of status epilepticus

Epistatus is characterized by irreparable consequences. Statistics. With symptomatic ES, mortality is 30–50%. With ES in patients with epilepsy - 5%.

If ES lasts more than an hour, then patients will face serious consequences:

- Diffuse saturation of brain tissue with fluid, called cerebral edema and accompanied by oxygen starvation;

- Critically low blood pressure;

- Excessive levels of lactic acid, called lactic acidosis;

- Violation of water-salt balance;

- For children, characteristic signs are delays in the development and formation of the psyche, which can lead to mental retardation.

Non-convulsive epistatus is considered less dangerous compared to generalized epistatus. Nevertheless, complications of status epilepticus often find expression in disturbances of perception, attitude, thinking, memory, and understanding.