When hemoglobin breaks down in sideroblast cells, hemosiderin is formed - a pigment containing iron molecules. It is deposited in the structures of the bone marrow, in the liver, in the spleen, in the sweat and salivary glands and in other organs. The main function of the pigment is the deposition and transfer of oxygen, as well as iron molecules, and participation in the transformation of biochemical complexes. With certain changes in the body, the synthesis of iron-containing compounds is activated.

Hemosiderosis (capillaritis, hemorrhagic pigmentary dermatosis) is a disease from the category of pigmentary dystrophies associated with metabolic disorders and excessive accumulation of hemosiderin in tissues and blood vessels. The skin and internal organs are affected. Deposits of hemoglobinogenic pigment can be widespread or local. Establishing the nature of the disease is difficult. Treatment is carried out by dermatologists, pulmonologists, hematologists, immunologists and other specialists.

About the reasons for the development of hemosiderosis

Skin hemosiderosis can be primary or secondary, developing due to injuries and skin infections.

The causes of primary skin capillaritis may be the following factors:

- vascular changes due to the presence of hypertension, varicose veins, etc.

- various endocrine disorders - the patient has diabetes mellitus and other pathologies.

Secondary hemosiderosis of the dermis can be caused by:

- scratching the skin, damage, injuries;

- skin diseases – dermatitis, neurodermatitis, etc.;

- pustular skin diseases.

Risk factors that can provoke the development of the disease include:

- frequent hypothermia;

- stress;

- excessive physical activity;

- taking diuretic, anti-inflammatory and antibacterial drugs.

Generalized hemosiderosis develops against the background of previous diseases. Most often, the main causes are systemic blood diseases, autoimmune diseases, severe intoxications and exposure to infectious agents. Increased deposition of hemosiderin may be due to:

- leukemia;

- sepsis, malaria and other infections;

- the presence of Rh conflict;

- liver damage;

- constant blood transfusions;

- taking large doses of sulfonamides, drugs containing quinine or lead.

Why iron-containing pigment accumulates in the lungs is not entirely clear. Often the reasons lie in genetic predisposition, in congenital anomalies of the pulmonary capillaries, in existing heart diseases.

2. Reasons

The immediate cause is the penetration and accumulation of red blood cells in the pulmonary parenchyma (with subsequent release of hemosiderin), due to frequent capillary bleeding. However, the reason for the failure of the vascular walls and their increased permeability, which leads to the selective deposition of iron oxide, remains unknown. The most developed and well-reasoned hypotheses today are the hypotheses about a congenital hereditary anomaly (which is confirmed, in particular, by known cases of familial hemosiderosis) and/or about the autoimmune-allergic nature of the disease (which is supported by cases of hemosiderosis in combination with allergic sensitivity, and also the therapeutic effectiveness of hormonal agents). In addition, a number of authors consider the etiopathogenetic role of infections, primarily viral and possibly protozoal (malarial plasmodium), to be proven.

Visit our Pulmonology page

Characteristic symptoms

Clinical manifestations depend on where the hemoglobinogenic pigment accumulates.

Pulmonary hemosiderosis

Idiopathic (primary) pulmonary hemosiderosis is manifested by the following symptoms:

- moist cough;

- elevated temperature, fever;

- presence of shortness of breath and respiratory failure;

- cough with blood;

- chest pain, severe dizziness;

- pale skin;

- hypochromic anemia;

- skin cyanosis;

- enlarged spleen and liver;

- drop in blood pressure, heart rhythm disturbance.

Brown purpura of the lungs, usually found in children and young adults, is a serious disease. With a prolonged course of the disease, recurrent infarction-pneumonia and other pathologies very often develop.

At CELT you can consult a pulmonologist.

- Initial consultation – 3,500

- Repeated consultation – 2,300

Make an appointment

Skin hemosiderosis

The following symptoms are characteristic:

- the appearance of brown pigment spots in the lower extremities and other parts of the body;

- hemorrhagic rash on the skin of the hands, feet, forearms, etc.;

- slight itching in problem areas;

- formation of plaques, nodules and papules.

Chronic hemosiderosis of the dermis is usually diagnosed in men over 30 years of age. The disease occurs without damage to internal organs.

At CELT you can consult a dermatologist.

- Initial consultation – 3,500

- Repeated consultation – 2,300

Make an appointment

Purpurative pigmentary dermatosis of the liver is manifested by enlargement of the organ, its soreness, yellowness of the integument, and the presence of a pigmented rash on the hands, in the armpits, and on the face. If the kidneys are damaged, swelling in the legs, dyspepsia, changes in taste, lower back pain, etc. appear.

Liver lesions in hemochromatosis: clinical manifestations and diagnosis

This article provides information about the etiopathogenesis of hemochromatosis, presents the clinical symptoms of the disease, as well as methods of laboratory and instrumental diagnostics, and the main approaches to therapy.

The influence of iron overload syndrome on the course of liver diseases for which iron has tropism

Hemochromatosis is a hereditary or acquired disease from the group of storage diseases, characterized by impaired iron metabolism with its pathologically high deposition in vital organs, in particular the liver [1]. Iron overload syndrome can independently cause liver pathology or contribute to the progression of existing chronic diffuse liver diseases [2].

Iron overload (hemosiderosis) is a pathophysiological process associated with the formation of deposits of hemosiderin (a dark yellow pigment based on iron oxide). Hemosiderosis begins primarily in the liver tissues, subsequently affecting other tissues of the body (kidneys, heart, brain, etc.). Hemosiderosis stimulates the development of proinflammatory reactions, intensification of oxidative stress (including lipid peroxidation), damage to organ parenchyma with the development of fibrosis [3].

The diagnosis is most often made at the stage of established hemochromatosis - with cirrhosis, cardiopathy and/or diabetes, the presence of phenotypic signs of iron overload - hyperferritinemia (> 200 ng/ml in women and > 300 ng/ml in men), transferrin saturation (> 45%).

Treatment options at the stage of mature hemochromatosis, when the ferritin level exceeds 1000 ng/ml, are limited, since hemosiderin, which is degraded ferritin, is extremely difficult to remove from tissues [4].

The main problem in the differential diagnosis of iron overload syndrome is establishing the primary nature of excess iron accumulation. In addition to making a diagnosis for a particular patient, confirmation of the primary (hereditary) nature of the disease determines the need for examination and prevention of the development of the disease in relatives [5].

Epidemiology

The high incidence of hereditary hemochromatosis (according to some data, up to eight cases per 1000 population) suggests heterozygous carriage of the pathological gene in 10–13% of the population. In Russia, the diagnosis of hereditary hemochromatosis is established extremely rarely or not at all, which is explained by the significant phenotypic heterogeneity of the disease and the absence of pathognomonic symptoms [5].

Hemochromatosis is diagnosed in men 5–10 times more often than in women. The lower frequency of detection of the disease in women is due, in particular, to menstrual blood loss. In men, the disease is usually diagnosed at the age of 40–60 years, in women - after menopause [5]. Juvenile hemochromatosis manifests at a young age (10–30 years) and is characterized by severe iron overload syndrome, accompanied by rapidly progressing signs of liver and heart damage. The frequency of clinically manifest forms of liver damage due to hemochromatosis in the population is two cases per 1000 inhabitants [6].

Etiopathogenesis

Primary hemochromatosis (hereditary, classical, bronze diabetes, pigmented cirrhosis of the liver, Troisier-Hanot-Choffard syndrome) is caused by numerous genetic mutations. Secondary hemochromatosis is diagnosed in 20% of children due to blood transfusions and long-term treatment with iron supplements, as well as in 40% of patients with diffuse liver diseases [1, 3, 7]. Iron overload syndrome aggravates the course of liver diseases to which iron has a tropism: viral hepatitis, liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension, alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, Wilson's disease and other chronic diffuse liver diseases (table) [1, 8].

Conditions accompanied by increased iron accumulation in liver cells

Liver diseases affect all metabolic processes in the body, including iron metabolism. The liver synthesizes most proteins - iron transporters (transferrin, apoferritin, ferroportin), regulatory proteins (peptide hepcidin). In addition, the liver is the main depot of iron. When overloaded with iron, it is the liver that suffers first, since iron becomes a powerful endogenous inducer of free radical oxidation (Fenton reaction), which leads to the destruction of cell membranes and cell death. At the same time, increased expression of transforming growth factor beta-1 enhances collagen synthesis, which promotes the development of connective tissue in the liver, that is, fibrosis and cirrhosis [6, 9].

Classification and clinical manifestations

Clinical manifestations of hemochromatosis are polymorphic and nonspecific, and in all patients, regardless of the form, pathological changes in the liver are detected, leading to its enlargement. Often, patients with hemochromatosis with liver pathology are mistakenly diagnosed with reactive and cryptogenic hepatitis [1].

Symptoms of liver damage are detected either accidentally or at the stage of cirrhosis and its complications, which marks an unfavorable outcome of the disease [6, 10].

The predominance of signs of damage to certain organs and systems served as the basis for identifying four clinical forms of hereditary hemochromatosis [5, 6, 11]:

- HFE (classic form) is the most common type of hemochromatosis associated with mutations of the HFE gene on chromosome 6; a classic triad of signs is observed (diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis and skin pigmentation), often in combination with symptoms of damage to the heart and endocrine glands, against the background of increased serum levels of iron metabolism;

- HFE 2 (juvenile form). This form is rare and is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. Mutations in this type of hemochromatosis are located in the HAMP gene, which is responsible for the synthesis of hepcidin in the liver, which modulates iron metabolism by reducing intestinal absorption of iron, slowing its release from liver stores and regulating iron uptake by reticuloendothelial cells. As a rule, the first signs of the disease are persistent abdominal pain combined with delayed sexual development and signs of liver and myocardial damage (rhythm and conduction disturbances);

- HFE 3 (hemochromatosis type 3). The genetic basis of type 3 hemochromatosis is made up of mutations in the HJV gene, which encodes the synthesis of transferrin receptor type 2, which is a modulator of hepcidin production in response to excess iron in the body. Inherited in an autosomal recessive manner, clinically it differs little from the classical form;

- HFE 4 (autosomal dominant hemochromatosis). In this type of disease, iron is deposited predominantly in the reticuloendothelial system. Significant iron deposits are found in Kupffer cells, which determines the presence of signs of liver damage in the clinical picture. Clinical debut usually occurs in old age.

Separately, there is a 5th type of hemochromatosis - neonatal. The disease is characterized by intrauterine growth retardation and begins with rapidly progressing symptoms of liver failure, leading to death soon after birth [6, 11].

Iron accumulation goes through several stages: from the asymptomatic period of iron overload to the formation of multiple organ failure [1].

Clinical stages of development of primary hemochromatosis

There are several stages of development of primary hemochromatosis:

- latent – the presence of a genetic defect in the absence of iron overload syndrome. At this stage, there is a gradual accumulation of iron;

- asymptomatic – absence of clinical manifestations of the disease with laboratory signs of iron overload syndrome;

- iron overload syndrome with early symptoms. The clinical picture is not very specific and is characterized by signs of asthenic syndrome;

- iron overload syndrome with target organ damage. There are signs of damage to individual organs (signs of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, pancreatogenic diabetes mellitus, heart failure and arrhythmias, damage to the pituitary gland, adrenal glands, hypogonadism, etc.).

Typically, hemochromatosis with severe symptoms is diagnosed in men over 40 years of age. Typical complaints: weakness, lethargy, abdominal and joint pain, melasma, decreased libido. HFE-associated hemochromatosis is distinguished by symmetrical arthropathy affecting complex joints. Specific damage to the proximal joints of the phalanges, metacarpophalangeal joints, wrists, knees and intervertebral joints. Important clinical manifestations of the disease include hepatomegaly, cirrhosis, diabetes and skin lesions [8].

Hemolytic and iatrogenic transfusion overload with iron is clinically much more severe, leads to damage to the heart, liver (up to cirrhosis) and multiple organ failure already in childhood, requires the prescription of iron chelators and usually does not cause diagnostic difficulties [9].

Diagnostics

Recently, there has been a transformation in the clinical picture of hemochromatosis: patients with the classic clinical triad described by Dutournier in 1885 are less common; the disease is more often diagnosed at preclinical stages, when the main symptoms of the disease are absent [5].

Diagnosis is based primarily on clinical symptoms in combination with hereditary predisposition. During the history taking process, clinical signs of hemochromatosis are identified. If they are present, biochemical parameters of increased iron levels are checked [8].

Iron metabolism is determined by studying five main diagnostic markers [2, 9, 12]:

- serum iron (levels are elevated in most cases, but not always);

- ferritin (in men > 300 mcg/l, in women > 200 mcg/l);

- transferrin;

- total iron binding capacity of serum (TIBC) (

- degree of transferrin saturation with iron/transferrin iron saturation (TSI).

A sensitive test is the determination of the concentration of ferritin in the blood serum, which is directly proportional to the total iron reserve in the body. An increase in ferritin levels greater than 1000 ng/ml indicates severe iron overload [11].

The last indicator is calculated and represents the ratio of serum iron to total body weight. Normally, the SVTZ does not exceed 40%. According to most researchers, the degree of transferrin saturation of more than 42% is considered increased. At the preclinical stage, a marker of iron excess is SNFA > 45%. In clinically formed hereditary hemochromatosis, the LTFA approaches 100% and even exceeds this threshold [9, 12].

General clinical and biochemical blood tests should also include a general analysis, proteinogram, determination of bilirubin and its fractions, analysis of the activity of aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, alkaline phosphatase, ceruloplasmin.

Molecular genetic research to verify the diagnosis of hereditary hemochromatosis is carried out on patients [13], as well as their close relatives with confirmed hereditary hemochromatosis. The diagnosis can be considered established when the patient is a homozygous carrier of C282Y

or a complex heterozygous carrier

C282Y/H63D

. In these cases, a liver biopsy is usually not required.

Isolated heterozygous mutation C282Y

and

H63D

in combination with signs of iron overload, hepatodepression, increased activity of serum aminotransferases require a puncture biopsy of the liver with a morphological examination of the biopsy and staining with Perls reagent (Prussian blue) for the iron content in hepatocytes, as well as a biochemical analysis of the concentration of iron in the liver tissue (Liver Iron Content, LIC) [6, 7, 13]. The degree of activity of the pathological process in a liver biopsy is determined by the histological activity index according to the Knodel classification [1]. The level of iron in biopsy specimens above 70 mcg per 1 g of native liver is considered pathological.

Although liver biopsy can provide very valuable information, it is an invasive test and is associated with a certain risk of complications [8].

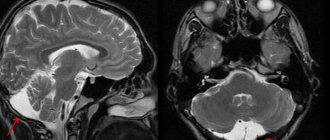

Important instrumental studies remain ultrasound examination of the abdominal organs, radioisotope scanning of the liver with technetium (99mTc), magnetic resonance imaging of the liver and heart in T2-weighted mode (detects the accumulation of iron in these organs at the preclinical stage) [7, 14, 15].

Treatment

The goals of treatment for hemochromatosis are to remove excess iron from the body and prevent complications of the disease (diabetes mellitus, liver failure, cardiomyopathy) [5].

Patients with hemochromatosis must follow a certain dietary regimen, which involves limiting the consumption of foods rich in iron (meat, buckwheat, apples, pomegranates) and vitamin C, and excluding alcohol from the diet, especially red wine. In addition, it is not recommended to take multivitamin-mineral complexes and dietary supplements containing iron and vitamin C [5, 6, 10, 16].

Phlebotomy (bloodletting, venesection) allows you to remove excess iron without significant side effects. Initiating phlebotomy treatment before the development of cirrhosis can reduce morbidity and mortality [8]. Regular phlebotomy is considered the most effective and safe treatment for hemochromatosis. Therapeutic phlebotomy (500 ml of blood), allowing the removal of 250 mg of iron with each procedure, should be performed weekly. The decrease in hematocrit after each phlebotomy session should not exceed 20% (recommendations of the American Liver Association). Taking into account the fact that treatment is lifelong, venesections are performed 4–6 times a year [5, 6, 8, 10].

The effectiveness of phlebotomy is assessed by reducing asthenic syndrome, hepatomegaly, skin pigmentation, and improving laboratory parameters (reducing hyperenzymemia, compensation of carbohydrate metabolism).

Other treatments for hemochromatosis include plasmapheresis, cytapheresis and hemosorption. They are also aimed at removing excess iron from the body [6].

Chelation therapy

Chelators are drugs that can bind and remove excess iron from the body. According to the modern concept, patients receiving systematic replacement transfusions of red blood cells require adequate chelation therapy aimed at reducing the level of toxic iron inside cells and in the extracellular space, total iron reserves in the body and, as a result, preventing the toxic effects of free iron [5, 7, 8, 17].

Chelation therapy (deferoxamine mesylate) plays a less important role in the treatment of hereditary hemochromatosis than phlebotomy and may be associated with side effects. The use of chelators allows you to remove a significantly smaller amount of iron (no more than 100 mg per week).

Deferoxamine (Desferal) is used at a dose of 1 g/day intramuscularly. The use of deferasirox (Exjade) is considered the most rational. The drug is available in the form of tablets for oral use and contains 125, 250 or 500 mg of deferasirox. Exjade is an oral drug that selectively binds iron (eg, Fe3+ radicals) [5, 8, 17].

Forecast

Patients who have had early diagnosis of hemochromatosis and started timely adequate treatment have a favorable prognosis. In the case of late diagnosis of the disease, in the presence of liver cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, and cardiomyopathy, the prognosis is determined by the severity of these irreversible complications. The five-year survival rate of patients with hemochromatosis reaches 93–72% (18% in the absence of treatment), the ten-year survival rate is 77–47% (0–6% in the absence of treatment) [6].

Almost 30% of patients with hemochromatosis develop liver cancer. The risk of its occurrence in patients with hemochromatosis is 200 times higher than the average in the population, and does not correlate with either the degree of liver damage or the effectiveness of the treatment. This circumstance determines the need for screening for hepatocellular carcinoma once every six months (ultrasound examination of the abdominal organs, computed tomography, alpha-fetoprotein concentration) [5, 10].

Diagnostics

A dermatologist examines the patient, examines the nature of the rash and the presence of characteristic signs. Laboratory tests are required - blood biochemistry with determination of iron levels, general urine tests, PCR tests. The content of sputum and urine is analyzed using a desferal test. To clarify the diagnosis, the affected segments are sent for a biopsy. Histological studies of the skin, bone marrow, lungs, lymphatic tissues, liver, and kidneys help detect pigment deposits. For diagnostic purposes, bronchoscopy with examination of lavage water can be performed, a chest x-ray, MRI, and computed tomography may be performed.

Pathogenesis

Patol, the process develops in the area of capillaries and the precapillary network of the dermis, where there is a change in the endothelium of the capillaries and an increase in hydrostatic pressure in them. O. K. Shaposhnikov (1974) suggests that the accumulation of hemosiderin in the skin may depend on the release of both the liquid part of blood and red blood cells and one blood pigment (hemosiderin) from the vessels. In some patients, deviations from the norm of some indicators of blood clotting are determined, in particular a decrease in the number of platelets, a violation of iron metabolism.

Therapeutic tactics of hemosiderosis

Treatment is prescribed by a dermatologist and depends on the clinical manifestations and severity of the disease.

Conservative therapy:

- Prescription of glucocorticosteroids. These are first-line drugs that suppress inflammation, restore physiological processes, stop autoimmune processes and stabilize cell walls. In 50% of cases, drugs cure hemosiderosis.

- Immunosuppressants in combination with plasmapheresis. Cytostatics and other immunosuppressants suppress the immune system, including at the cellular level, and prevent the formation of new antibodies. The blood is filtered using a special apparatus. Toxins, accumulated antibodies and immune complexes that increase vascular permeability are removed from tissues, vessels and cells.

- Vitamin complexes containing vitamin C, rutin, calcium, etc.

- Iron supplements in the presence of anemia and other complications.

- Hemostatic drugs.

- Medicines to eliminate symptoms of the disease. If necessary, bronchodilators, angioprotectors, anticoagulants, antiplatelet agents, etc. are prescribed.

- Corticosteroid ointments are prescribed locally.

- Inhalations with oxygen.

- Cryotherapy.

In severe cases, doctors perform a splenectomy, and patients have their spleen removed to achieve stable remission. They resort to blood transfusion, PUVA therapy, and prescribe drugs that help remove iron from the body.

Complications

If a patient with capillaritis does not receive proper treatment, dangerous complications develop that can lead to disability and death. Advanced forms of pulmonary hemosiderosis, when the pathological process affects the alveoli, are especially difficult to treat.

Possible complications:

- extensive pulmonary infarction;

- acute respiratory failure;

- multiple internal hemorrhages;

- constant overload of the heart and the formation of cor pulmonale;

- persistent increase in blood pressure;

- spontaneous pneumothorax.

Hemosiderosis of the skin has a favorable course. In advanced forms of the disease, cosmetic defects appear that require proper correction.

Treatment

Rice.

27. Deposition of hemosiderin in the lung during essential pulmonary hemosiderosis (macropreparation). Treatment measures are carried out primarily in relation to the underlying disease. In addition, bloodletting is used, which is especially effective for diffuse G. accompanying idiopathic hemachromatosis. Bloodletting in a volume of 500 ml is equivalent to the removal of 200 mg of iron. However, in case of iron-refractory anemia, this method, which requires constant and systematic blood transfusions, is not justified [R. M. Bannerman]. In the treatment of secondary hepatitis (complications of liver cirrhosis), the drug diethylenetriamine penta-acetate [McDonald, Smith (RA McDonald, RS Smith)] is effective, but its injections are painful and sometimes cause side effects. The introduction of desferal into the wedge and practice has opened up new opportunities in the treatment of G. of various origins. Desferal is usually administered intramuscularly at a dose of 1-3 g per day. The duration of one course of treatment is at least 3 weeks. There are instructions [F. Wohler] on the use of desferal for a year or more in patients with idiopathic hemochromatosis. The main criterion determining the duration of treatment is the excretion of iron in the urine; if daily iron excretion does not exceed 1.0-1.5 mg, deferoxamine injections are stopped. From other to lay down. agents, you can specify complexing compounds - thetacine-calcium (see) and pentacine (see).

Essential pulmonary hemosiderosis (tsvetn. fig. 26 and 27) occupies a special place, because it is fundamentally different in etiology, pathogenesis and clinic from hemochromatosis. Hemosiderin deposits are found only in the lungs, which is reflected in its old names - brown induration of the lungs, essential brown induration of the lungs, pulmonary stroke, congenital bleeding into the lungs (see Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis).

Bibliography:

Dolgoplosk N. A. and Skaldina A. S. A case of essential hemosiderosis of the lungs, Vestn, rentgenol, i radiol., No. 1, p. 88, 1971, bibliography; Martynov S. M. and Sheremeta N. A. About transfusion hyperhemosideroses and hemochromatosis in leukemia, hemoblastosis and aplastic anemia* in the book: Sovrem. Problem, hematol. and overflow, blood, ed. A. E. Kiseleva et al., c. 38, p. 243, M., 1966; Fainshtein F. E. et al. The use of desferal and some data on hemosiderosis in hypo- and aplastic anemia, Problem < hematol. and overflow, blood, vol. 13, no. 8, p. 31, 1968, bibliogr.; Khutsishvili G. E. Desferal test in the diagnosis of hemosiderosis in patients with hemoglobinopathies, Laboratory, case, No. 9, p. 660, 1971* bibliogr.; Blood and its disorders, ed. by RM Hardisty a. DJ Weatherall, Oxford, 1974; Bothwell T. H. a. Finch CA Iron metabolism, Boston, 1962; Clinical symposium on iron deficiency, ed., by L. Hallberg ao, L.—NY, 1970; Iron metabolism, ed. by F. Gross, B., 1964; Mac Donald RA Hemochromatosis and hemosiderosis, Springfield, 1964, bibliogr.; Roberts LN, Montes-s ori G. a. P a 11 erson JG Idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis, Amer. Rev. resp. Dis., v. 106, p. 904, 1972.

L. A. Danilina.

Clinic

Clinically, the following forms of G. are distinguished: 1. White skin atrophy. 2. Arc-shaped telangiectatic purpura. 3. Itchy purpura. 4. Annular telangiectatic purpura. 5. Lichenoid purpurosa and pigmentary angiodermatitis. 6. Orthostatic purpura. 7. Ocher dermatitis. 8. Progressive pigmentary dermatosis. 9. Reticular senile hemosiderosis of the skin (senile Bateman's purpura). 10. Eczematid-like purpura.

G. to. is observed mainly in men. Characterized by sharply demarcated spots of brownish-red color, of various shades, which do not disappear with pressure without inflammatory changes in the surrounding skin.

White skin atrophy (capillaritis alba)

- a rare form of G. k., described by G. Milian in 1929. It is characterized by thinning (atrophy) of the skin on the anterior surface of the legs in the form of whitish, slightly sunken spots of a round shape with clear boundaries merging with each other; around the spots - hyperpigmentation due to the deposition of hemosiderin, telangiectasia. This form often develops against the background of varicose veins of the lower extremities, leading to recurrent hron, capillaritis. There is also an assumption about structural disorders of connective tissue. Formed atrophic changes in the skin are irreversible.

Arcuate telangiectatic purpura

described by Tourain (N. Tourain) in 1934. Characterized by the appearance on the legs, ch. arr. in the area of the ankles, one, or less often several, lesions, in the form of a yellowish-pinkish spot, reaching 10-15 cm in size due to centrifugal growth and breaking up into half rings, intermittent arcuate segments, around which hemosiderin impregnation and telangiectasia are observed. Maybe wedge, and gistol. similar to Majocchi's disease.

Itchy purpura

described by LJ Loewenthal in 1954; resembles eczematid-like purpura, but is characterized by intense itching, numerous scratches and lichenification (see).

Annular telangiectatic purpura

- rare hemorrhagic pigmentary dermatosis - see Majocchi disease.

Skin rashes with lichenoid purpurous and Gougerot-Blum angiodermatitis pigmentosa.

Lichenoid purpurosa and angiodermatitis pigmentosa

described by Gougerot and Blum (H. Gougerot, P. Blum) in 1925 under the name purpura angiosclereux prurigineux avec elements lichenoides. The disease is characterized by hron, course and predominant localization of the lesion in the lower extremities. On the skin of the legs and thighs, against a purpuric-pigmented background, there are lichenoid-nodular rashes of a reddish-brownish color the size of a pinhead (Fig.), less often small round plaques covered with small scales; sometimes the rash is accompanied by itching. Generalization of the process is possible, which some authors consider as an independent form of the disease - dermatitis purpurica et pigmentata, papuloides et reticulata, tarde generalisata (Le Coulant - Texier - Maleville, 1960). In this form, the rash spreads in the form of outbreaks on the skin of the torso, face, and upper extremities.

Orthostatic purpura

described in 1904 by Achard and Grenet. Skin changes are observed on the lower extremities with cardiovascular failure, kidney disease, liver disease in older people with prolonged standing.

Ocher dermatitis

(syn.: yellow ocher dermatitis, pigmentary and purpuric angiodermatitis of the lower extremities, Janselm's angiosclerotic purpura) was described as Favre-Ché syndrome in 1924-1926. Develops as a result of constant repeated tiny hemorrhages, mainly on the legs and feet in elderly men suffering from hl. arr. local circulatory disorders (varicose veins, thrombophlebitis, etc.). However, general vascular disorders as a result of atherosclerosis and hypertension also play a certain role. With a long-term process, continuous spotted lesions are formed, up to 6-10 cm in diameter, and more rusty-red in color; on them and around them, depending on the activity of the process, there is a greater or lesser amount of fresh purpuric and petechial elements. There is usually no itching. Skin atrophy gradually develops, and trophic ulcers of the lower leg may form. A variation of this form of G. to. is acroangiodermatitis of the feet [described by Mali (JW Mali, 1965) et al.], which also develops against the background of venous insufficiency, but is localized in the area of the feet; characterized by brown-blue spots or plaques, sometimes with a papillomatous surface, from 1 to 4 cm in diameter, prone to ulceration; in the ankle area there is hyperpigmentation with small atrophic areas.

Progressive pigmentary dermatosis

- a rare disease of unknown etiology - see. Schamberg's disease.

Reticular senile hemosiderosis of the skin

(syn.: reticular hemosiderosis of the elderly, senile Bateman's purpura, purpuric, telangiectatic dermatitis) was described by Bateman (Th. Bateman, 1818) under the name purpura senilis in the elderly. Patol, the process is caused by atherosclerotic changes in the vascular wall. Usually, small brownish-brownish spots, petechiae and telangiectasia appear on the legs and feet, forearms and dorsum of the hands; Sometimes itching is noted.

Eczematid purpura

described by Doucas and Kapetanakis (G. Doucas, J. Kapetanakis) in 1953. Characterized by the appearance on the trunk and limbs of numerous eczema-like erythemato-squamous spots of yellowish and yellowish-brownish color, as well as papular-hemorrhagic, sometimes confluent rashes; Slight itching is often observed. When gistol, examination, in addition to the general signs of G., spongiosis is noted.