Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) - symptoms and treatment

If patients have cough, sputum production, shortness of breath, and risk factors for developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease have been identified, then they should all be diagnosed with COPD.

In order to establish a diagnosis, clinical examination (complaints, anamnesis, physical examination) are taken into account.

A physical examination may reveal symptoms characteristic of long-term bronchitis: “watch glasses” and/or “drumsticks” (deformation of the fingers), tachypnea (rapid breathing) and shortness of breath, changes in the shape of the chest (emphysema is characterized by a barrel-shaped shape), small its mobility during breathing, retraction of the intercostal spaces with the development of respiratory failure, drooping of the borders of the lungs, change in percussion sound to a box sound, weakened vesicular breathing or dry wheezing, which intensifies with forced exhalation (that is, rapid exhalation after a deep inhalation). Heart sounds may be difficult to hear. In later stages, diffuse cyanosis, severe shortness of breath, and peripheral edema may occur. For convenience, the disease is divided into two clinical forms: emphysematous and bronchitis. Although in practical medicine, cases of a mixed form of the disease are more common.

The most important stage in diagnosing COPD is an analysis of pulmonary function (PRF) . It is necessary not only to determine the diagnosis, but also to establish the severity of the disease, draw up an individual treatment plan, determine the effectiveness of therapy, clarify the prognosis of the course of the disease and assess the ability to work. Establishing the percentage ratio of FEV1/FVC is most often used in medical practice. A decrease in the volume of forced expiration in the first second to the forced vital capacity of the lungs FEV1/FVC to 70% is the initial sign of airflow limitation even when FEV1>80% of the proper value is preserved. A low peak expiratory air flow rate, which varies slightly with the use of bronchodilators, also speaks in favor of COPD. For newly diagnosed complaints and changes in respiratory function indicators, spirometry is repeated throughout the year. Obstruction is defined as chronic if it occurs at least 3 times per year (despite treatment), and COPD is diagnosed.

Monitoring FEV 1 is an important method to confirm the diagnosis. Spireometric measurement of FEV1 is carried out repeatedly over several years. The rate of annual decline in FEV1 for mature adults is within 30 ml per year. For patients with COPD, a typical indicator of such a drop is 50 ml per year or more.

A bronchodilator test is a primary examination during which the maximum FEV1 value is determined, the stage and severity of COPD is established, and bronchial asthma is excluded (if the result is positive), the tactics and volume of treatment are selected, the effectiveness of therapy is assessed and the course of the disease is predicted. It is very important to distinguish COPD from bronchial asthma, since these common diseases have the same clinical manifestation - broncho-obstructive syndrome. However, the approach to treating one disease is different from another. The main distinguishing feature in diagnosis is the reversibility of bronchial obstruction, which is a characteristic feature of bronchial asthma. It has been found that in people diagnosed with COPD after taking a bronchodilator, the percentage increase in FEV1 is less than 12% of the initial value (or ≤200 ml), and in patients with bronchial asthma it usually exceeds 15%.

Chest X-ray is of auxiliary value, since changes appear only in the later stages of the disease.

An ECG can detect changes that are characteristic of cor pulmonale.

Echocardiography is necessary to identify symptoms of pulmonary hypertension and changes in the right heart.

Complete blood count - it can be used to evaluate hemoglobin and hematocrit (may be elevated due to erythrocytosis).

Determination of the level of oxygen in the blood (SpO2) - pulse oximetry, a non-invasive test to clarify the severity of respiratory failure, usually in patients with severe bronchial obstruction. Blood oxygen saturation less than 88%, determined at rest, indicates severe hypoxemia and the need for oxygen therapy.

COPD: review of Russian and international clinical guidelines

| Sources: 2021 Report Global strategy for prevention, diagnosis and management of COPD (Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease, GOLD 2021) Pharmacologic Management of COPD, An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline (ATS 2020) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management NICE guideline (NICE 2018) Clinical recommendations. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (Russian Respiratory Society (RPO 2018) |

Classification of COPD

Figure 1. Revised COPD assessment framework in the GOLD 2021 guidelines

| Spirometry |

| Symptom assessment: mMRC scale (modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale) or CAT test (COPD Assessment Test) |

| Estimation of the number of moderate and severe exacerbations |

| Result: COPD severity 1-4; group A, B, C or D |

Table 1. Spirometric classification of COPD

| Recommendations | Severity* | Characteristic |

| GOLD, 2021; NICE 2018; RPO, 2018 | GOLD 1: light | FEV1 ≥ 80% |

| GOLD 2: medium-heavy | 50% ≤ FEV1 | |

| GOLD 3: heavy | 30% ≤ FEV1 | |

| GOLD 4: extremely hard** | FEV1 |

Notes: *Classification is given for patients with FEV1/FVC ratio

**According to NICE 2021 and RPO 2021 guidelines, the criterion for COPD grade 4 may be FEV1

Abbreviations:

GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease - Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; NICE, The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence - UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; RRO – Russian Respiratory Society;

FEV1 – forced expiratory volume in the first second; FVC – forced vital capacity of the lungs.

Table 2. Groups of patients with COPD

| Recommendations | Characteristics | Group of patients |

| GOLD, 2021 | mMRC 0–1 or CAT exacerbations 0 or 1 (not leading to hospitalization) | A |

| mMRC ≥ 2 or CAT ≥ 10; exacerbations 0 or 1 (not leading to hospitalization) | B | |

| mMRC 0-1 or CAT ≥ 2 or ≥ 1 exacerbations leading to hospitalization | C | |

| mMRC ≥ 2 or CAT ≥ 10; ≥ 2 or ≥ 1 exacerbations leading to hospitalization | D | |

| RPO, 2021 (based on the 2011 GOLD classification) | GOLD 1–2, exacerbations per year ≤1, mMRC 0–1, CAT | A |

| GOLD 1–2, exacerbations per year ≤1, mMRC ≥2, CAT ≥ 10 | B | |

| GOLD 3–4, ≥2 exacerbations per year, mMRC 0–1, CAT | C | |

| GOLD 3–4, exacerbations per year ≥2, mMRC ≥2, CAT ≥ 10 | D |

Abbreviations:

mMRC, modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale - British Medical Research Council dyspnea scale;

CAT, COPD Assessment Test – COPD assessment test.

Drug therapy

Table 3. Pharmacotherapy for stable COPD

| Recommendations | Patient category | Initial therapy regimen | Transfer to another mode |

| All patients with COPD are recommended to: quit smoking; in the absence of contraindications, nicotine replacement therapy is possible; vaccination against influenza and pneumococcal infection; prescribing a short-acting bronchodilator for use as needed. | |||

| GOLD, 2021 | Group A | Bronchodilator | Continued shortness of breath - add LAMA or LABA In case of exacerbation, add LADA, LABA or ICS In case of pneumonia or lack of response, discontinuation of ICS |

| Group B | Monotherapy LAMA or LABA | ||

| Group C | LADA monotherapy | ||

| Group D | LADA monotherapy For severe symptoms, LAMA/LABA combinations are considered (e.g., CAT > 20); for eosinophil levels in the blood ≥ 300 cells/μL, ICS/LABA are considered. | ||

| ATS, 2020 | COPD with shortness of breath or exercise intolerance | LAMA/LABA combination is preferable to monotherapy | For repeated exacerbations 3-LAMA/LABA/ICS In the absence of exacerbations during the year, it is recommended to exclude ICS |

| RPO, 2018 | COPD with mild symptoms (mMRC | Initial monotherapy with LAMA or LABA | If symptoms persist or recurrent exacerbations1 - LAMA/LABA combination2 |

| For repeated exacerbations1 in patients with asthma or eosinophilia - LABA/ICS | |||

| COPD with severe symptoms (mMRC ≥2 or CAT≥10) | Prescribing a LAMA/LABA combination immediately after diagnosis | For repeated exacerbations1 in patients with asthma or eosinophilia - LAMA/LABA/ICS regimen2 | |

| NICE 2018 | Patients without asthma and signs of sensitivity to GCS4 | Combination LADAH/LABA | For repeated exacerbations1 - LAMA/LABA/ICS If there is no improvement within 3 months, exclude ICS |

| Signs of asthma or sensitivity to corticosteroids4 | LABA/ICS | If symptoms persist or recurrent exacerbations1 LAMA/LABA/ICS | |

Notes:

1Two or more moderate exacerbations within one year or at least one severe exacerbation requiring hospitalization;

2If exacerbations recur, phenotype-specific therapy is recommended (roflumilast, N-acetylcysteine, azithromycin, etc.);

3One or more exacerbations of COPD in the past year requiring antibiotics, oral steroids, or hospitalization;

4 The patient continues to experience shortness of breath or exacerbations despite smoking cessation, vaccination, non-pharmacological methods, and short-acting bronchodilators.

Abbreviations:

ATS, American Thoracic Society - American Thoracic Society;

BA – bronchial asthma; GCS - glucocorticosteroids; LABAs are long-acting β2-agonists; LADA – long-acting anticholinergics; ICS – inhaled glucocorticosteroids.

Table 4. Pharmacotherapy for exacerbations of COPD

| Recommendations | Patient category | Treatment Options |

| GOLD, 2021 | Initial treatment | CDBA with or without CDAC |

| Treatment to reduce time to stabilization and hospitalization | Systemic corticosteroids and antibiotics. Duration of therapy – 5–7 days | |

| RPO, 2018 | All patients with exacerbation of COPD | CDBA (salbutamol, fenoterol) or CDAC (ipratropium bromide) |

| Exacerbation of COPD requiring hospitalization | Systemic or inhaled GCS, antibiotic therapy may be prescribed |

Abbreviations: SABA – short-acting β2-agonists, CDAC – short-acting anticholinergics.

COPD and coronavirus infection

As outlined in the GOLD 2021 report, ACE2 protein expression is increased in COPD and may also be altered by ICS use. It is known that it is through these receptors that the new coronavirus penetrates human cells.

However, current evidence suggests that patients with COPD do not experience a significant increase in risk of infection, but do have an increased risk of hospitalization with COVID-19. There are also risks of more severe infection and death.

Table 5. GOLD 2021 recommendations for the period of the COVID-19 pandemic

| COPD studies | Carrying out spirometry and bronchoscopy only if necessary |

| Pharmacotherapy | Unchangeable, incl. use of ICS |

| PCR testing for coronavirus | For new or worsening respiratory symptoms, fever, and other signs that may be related to COVID; Negative COVID status must be confirmed before spirometry |

| Other COVID Research | For coronavirus pneumonia - computed tomography; For concomitant infections |

COPD and COVID-19: a brief overview of the relationships and approaches to providing medical care

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is one of the most common chronic respiratory diseases (CRRD). The prevalence of COPD among adults in the Russian Federation is 15.3%, and in some countries reaches 20%. The disease is associated with a poor quality of life for the patient, a significant social burden, and a risk of adverse outcomes. In COPD, in addition to inflammation, epithelial dysfunction, remodeling of the airways and lung tissue play a significant role. The pathological process in the lower respiratory tract in COPD is irreversible and progressive. Frequent and severe exacerbations of COPD are associated with a rapid decline in lung function and a risk of adverse outcomes, including death. Severe exacerbation, increasing respiratory failure and cardiovascular diseases are among the main causes of death in patients with COPD.

Often, during exacerbation of COPD, pathogenic microorganisms (viruses, bacteria, or a combination of both), including rhinovirus, respiratory syncytial virus, influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, metapneumovirus and coronavirus, are identified in 30-50% of patients. The new coronavirus infection, which broke out in December 2021 in the Chinese city of Wuhan, provoked a very serious epidemic situation, becoming a worldwide problem. Since the new disease already in 2021 led to severe damage to the respiratory system, often complicated by respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome, even at the first information about it, it began to be assumed that patients with chronic respiratory disease may develop the most unfavorable variants of the course. This was later confirmed by scientific publications: patients with COPD are at risk of severe COVID-19, associated with death. It is very likely that a patient with COPD who develops a severe form of COVID-19 is a multimorbid patient, which may further aggravate the prognosis.

The pathogenetic mechanisms of COVID-19 continue to be studied. It has been revealed that the main target of the virus in severe lung damage is alveolar epithelial cells, in the cytoplasm of which its replication occurs. The virus directly uses ACE2 as its receptor for intracellular entry. The affinity of SARS-CoV S protein and ACE2 is directly related to viral replication and disease severity. It is known that ACE2 expression is higher in COPD, especially in the presence of obesity. The combination of COPD and obesity appears to be an even stronger predictor of adverse outcomes from COVID-19. In patients with COPD, the risk of developing severe fibrotic changes in lung tissue during COVID-19 is probably higher, which is associated with increased production of IL-6 and other proinflammatory cytokines during COVID-19. In a study by F. Zhou et al. Among patients with COPD and COVID-19, only those whose IL-6 levels remained normal survived.

Basic principles of managing a patient with COPD during a respiratory infection epidemic. The tactics for managing patients with any disease must always comply with regulatory documents, including the current Federal Clinical Guidelines (FCR). In addition, it must currently comply with the Temporary Methodological Recommendations “Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of the new coronavirus infection COVID-19” approved by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (currently version 10). During the current COVID-19 pandemic, domestic and international experts in the field of COPD have published their expert opinion on various resources: it is necessary to treat COPD during the pandemic in the same way as before, in accordance with the developed principles (GOLD, February 2021). At the same time, if new respiratory symptoms appear or existing symptoms intensify in a patient with COPD, it is important to assess the presence/absence of signs of acute respiratory infection, carry out differential diagnosis with COVID-19 and others, determine whether there is an exacerbation of COPD or these are signs of another disease (for example, heart failure , other pathology). All these circumstances determine the further tactics of patient management. Previously, we published works in which attempts were made to summarize the information available at the time of writing about COPD and COVID-19, including brief algorithms for differential diagnosis and management.

If during COVID-19, even a mild course, there are signs of exacerbation of COPD, it is necessary to determine the severity of the exacerbation and manage the patient, taking into account the approaches described in the section of the FKR on COPD dedicated to the treatment of exacerbations, while simultaneously taking all measures and according to the approved protocols for the treatment of COVID-19 , and other comorbidity. Obviously, immediately after stopping an exacerbation of COPD, regular inhalation therapy for COPD should be prescribed according to the principles described in the current recommendations. Prevention of COVID-19 in patients with COPD includes generally accepted measures developed by WHO experts and the national health care system. Patients with COPD are strongly advised to follow all principles of prevention of respiratory infections, including COVID-19, to minimize the risk of infection. A short list includes:

— wearing a disposable medical mask (change every 2 hours) and disposable gloves in public places; — compliance with the rules of personal hygiene (washing hands with soap, using disposable wipes when sneezing, blowing your nose and coughing, touching your face only with clean wipes or washed hands); — maintaining physical distancing; - rinsing the nose with isotonic sodium chloride solution; — use of drugs for local (intranasal) use that have barrier functions; — if there is a high risk of infection, drug prophylaxis is possible (local use of recombinant interferon-alpha, oral agents); — timely seeking medical help (when the first symptoms of deterioration appear); - self-isolation if you suspect a disease.

Doctors who have patients with COPD under clinical observation need to continue it, but during the period of spread and epidemic of respiratory infections, prefer remote monitoring of the patient’s condition, the therapy being carried out and the prevention of risk factors.

Stages of occurrence

Staging of COPD is carried out on the basis of an objective measurement of the limitation of the expiratory air flow rate - the FEV1 parameter (forced expiratory volume in 1 s) during spirometry (study of the function of external respiration):

- Stage 1 (the mildest) – FEV1 more than 80% of the age norm;

- Stage 2 – FEV1 from 50 to 80% of the age norm;

- Stage 3 – FEV1 from 30 to 50% of the age norm;

- Stage 4 (the most severe) – FEV1 is less than 30% of the age norm.

In addition, to stratify the risk of complications and select optimal treatment for COPD, the severity of the main symptoms of the disease and the frequency of exacerbations are taken into account. Depending on these parameters, the patient is included in classification groups A, B, C or D (may change as a result of treatment).

2. Drug treatment of the disease

To treat COPD, medications are also used that can perform different functions. Yes, bronchodilators

help open the bronchi, which in turn makes breathing easier. These medications may be short-acting (to quickly relieve symptoms of the disease) or long-acting to help prevent them.

Anti-inflammatory drugs

to treat COPD symptoms (such as corticosteroids) may come in the form of tablets or inhalers that help the medicine go directly to the lungs.

Visit our Pulmonology page

Causes

- smoking (active and passive inhalation of tobacco smoke),

- regular inhalation of dust, combustion products (harmful industries)

Unfortunately, this disease is incurable, which is why the World Health Organization is actively calling on countries to combat tobacco smoking and conduct preventive and educational programs for the population. After all, you can prevent the threat of COPD by quitting smoking.

And even if the disease is incurable, you can cope with its manifestations and transfer its course into a controlled direction, the main thing is not to self-medicate and turn to qualified specialists in a timely manner.

Don't forget that almost all cases of COPD are preventable. And you can protect yourself by giving up the bad habit of smoking tobacco. Due to the fact that previously men smoked much more than women, the disease was considered mostly male, but with the widespread spread of this bad habit among women, the number of identified cases of COPD among them has also increased. Therefore, in our time, the gender division is not so clearly visible. People 40-50 years old and older are at risk.

Causes of the disease

In the development of COPD, both the properties of the human body (genetic predisposition) and the influence of environmental factors play a role.

The main environmental risk factors for the development of COPD are:

- Smoking (active and less often passive) is the main cause of COPD in developed countries.

- Combustion of biomass for cooking and heating of living spaces is a significant cause of COPD in developing countries.

- Occupational hazards.

- Outdoor air pollution.

- Impaired lung development in prenatal and childhood years.

- The presence of bronchial asthma and bronchial hyperreactivity.

The main genetic risk factor for the development of COPD and emphysema, primarily in young patients, is alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

Diagnostics

Diagnosis of COPD is one of the most pressing topics for a pulmonologist: the disease is widespread, and if diagnosed untimely, there is a high risk of the disease progressing to a severe form with high mortality. The main diagnostic method used everywhere is spirometry - the doctor measures the volume and speed of air flow exhaled at maximum effort. But in the pulmonology department of the Federal Scientific and Clinical Center of the Federal Medical and Biological Agency of Russia, in addition to spirometry, specialists also conduct other examinations of lung functionality, which make it possible to clarify the diagnosis and subsequently select effective treatment: body plethysmography, measurement of the diffusion capacity of the lungs, cardiorespiratory stress tests, a study of breathing during sleep, determination of nitric oxide in exhaled air etc. Laboratory diagnostics may also be required - blood and sputum tests to clarify the stage of the disease.

COPD in the practice of a therapist

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor

E.G. Silina, A.S. Volkova Key words:

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Tiffno index, GOLD

Summary:

The article discusses the definition of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the structure of the disease, pathogenesis, classifications, clinical picture, diagnostic methods and differential diagnosis, as well as treatment methods.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (GOLD definition) is a common disease characterized by persistent airflow limitation that is usually progressive and results from a chronic inflammatory response of the airways and lung tissue to exposure to inhaled noxious particles or gases.

GOLD is a program that was founded in 1998 and studies COPD. The last revision was in 2021.

According to WHO, COPD ranks 5th in prevalence among nosologies. The incidence of COPD is continuously increasing. . In Russia, during life, COPD is diagnosed much less frequently than it should be, and morphologists are very keen on this diagnosis, so the clinical diagnosis of COPD is made in 24% of cases, and according to autopsies, COPD is found in more than 68% of the deceased. Thus, we can talk about intravital underdiagnosis of COPD, which means insufficient treatment, and postmortem overdiagnosis.

In the structure of mortality in the Russian Federation from respiratory diseases, COPD ranks 2nd and accounts for 41%.

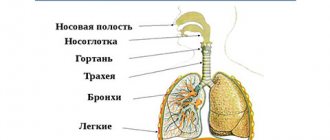

Let's consider the pathogenesis. Under the influence of risk factors, which most often include tobacco smoke, in the presence of some genetic predisposition, pulmonary inflammation and pathological changes in the lungs occur, in particular, obstructive bronchiolitis, hypersecretion of mucus and destruction of the alveolar wall.

The morphological substrate of COPD has long been known. We are talking about immune chronic inflammation, which develops not in the large bronchus, but in the terminal sections of the respiratory tract - the bronchioles. As a result, terminal bronchiolitis develops, emphysema develops with a gradual loss of elasticity, so-called air “traps” arise when the air during exhalation does not leave the required volume of the alveoli, ultimately leading to irreversible limitation of air flow.

The most important pathophysiological mechanism of COPD is hyperinflation. Pulmonary hyperinflation results from increased loss of elastic recoil of the lungs and occurs with increased airway resistance, loss of elastic recoil, and shortened expiratory time (shortness of breath).

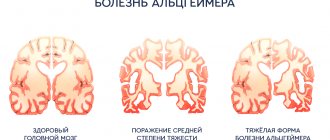

What morphological changes can we see in our patients? First, emphysema, which can be centrilobular and bullous, and as a result of long-term COPD, chronic cor pulmonale develops. Normally, the thickness of the wall of the right ventricle is 0.2-0.3 cm, but here we see a significant excess of this value.

Depending on the severity of emphysema, there are 3 morphological types of COPD: bronchointerstitial, emphysematous and truly obstructive.

Considering that in the diagnosis we must indicate the severity of bronchial obstruction, the severity of symptoms, the frequency of exacerbations and phenotype, we will consider the following classification. 1 – Spirometric (functional) classification of COPD. For this classification, we must conduct spirometry, and we will evaluate only 2 indicators: FEV1 and its relation to FVC (the so-called Tiffno index). If 15 minutes after inhalation of 400 mcg of salbutamol MF we obtain a Tiffno index of less than 70%, the diagnosis of COPD is confirmed. Next, depending on FEV1, we determine the degree and stage of COPD (1 mild - more than 80%, 2 moderate - from 50 to 79, 3 severe - from 30 to 49, 4 extremely severe - 29 or less).

The following COPD risk classification is ABCD. It is used to select pharmacological therapy and is based on the severity of symptoms and the frequency of exacerbations. In accordance with this classification, there are 4 risk stages for COPD. A – rare exacerbations, mild symptoms, B – rare exacerbations, severe symptoms, C – frequent exacerbations, mild symptoms, D – frequent exacerbations, severe symptoms.

Depending on the predominant mechanism of development of COPD, 2 phenotypes are distinguished - emphysematous, cachectic (elderly patients with emphysema, “pink” puffers) and metabolic, bronchitis (“blue edema”, younger patients with excess body weight and concomitant vascular pathology, which develops earlier here). chronic pulmonary heart disease, the prognosis is unfavorable in this type of patient).

Classification of severity of exacerbations. An exacerbation is an acute worsening of respiratory symptoms requiring additional therapy. There are 3 degrees of severity of exacerbations. With a mild degree, the patient needs to increase the volume of therapy, which can be carried out by the patient’s own efforts. With moderate severity, the patient needs to increase the volume of therapy, which requires consultation of the patient with a doctor. In severe cases, the patient/doctor notes a clear and/or rapid deterioration in the patient’s condition; hospitalization of the patient is required.

Clinical picture. The patient is over 40 years old, a smoker or a former smoker with many years of smoking experience. The presence of the following clinical symptoms: increasing expiratory shortness of breath at rest or during physical activity, chronic cough, sputum production, recurrent pulmonary infections, the presence of risk factors in the environment, the presence of a genetic predisposition. Cough daily/intermittent. More often during the day, rarely at night. Sputum production of any nature. Shortness of breath - progression, persistence, increase with physical activity, respiratory infections, slow, steady increase in respiratory symptoms. On examination: wheezing, diffuse warm cyanosis, symptoms of “watch glasses”, “drumsticks”, barrel-shaped chest, widened (more than 90 degrees) epigastric angle, bulging in the supraclavicular areas, widened intercostal spaces.

We can see a description of a patient with COPD in Ivan Bunin’s work “The Cheerful Yard.” “Yegor was whitish, shaggy, not big, but broad, with a high chest... he constantly sucked on his pipe, tearing himself up with a painful cough, and, clearing his throat, his swollen eyes shining, he wheezed for a long time, carried with his always raised chest.

He coughed from tobacco, he started smoking when he was eight years old, and he breathed deeply from the expansion of his lungs...”

Diagnosis of COPD and subsequent examination includes the following stages: assessment of risk factors, clarification of complaints and collection of anamnesis, physical examination (signs of broncho-obstruction, emphysema, cor pulmonale), instrumental research methods: spirometry (diagnosis of COPD), radiography / CT scan of the lungs (differential diagnosis , complications), ECHO-CG (pulmonary heart). Additionally, an alpha-antitrypsin study is carried out: COPD less than 50 years of age, predominantly basal emphysema, family history of emphysema at the age of less than 50 years.

Risk factors for COPD include internal, usually genetic, and external (smoking, air pollution, occupational hazards, social factors).

During the survey, clarification is required: the presence of complaints, the impact of risk factors, the severity of clinical symptoms, the frequency, duration and characteristics of exacerbations, the effectiveness of previous treatment measures, compliance, the correct technique of using inhalers, exercise tolerance, the presence of a hereditary predisposition to COPD and other pulmonary diseases.

To assess the severity of symptoms, there is a CAT test with a series of questions. Depending on the score, we determine the impact of symptoms on life.

The mMRC scale is used to assess the severity of shortness of breath. The boundary between a symptomatic and asymptomatic patient is 1 point; starting from 2 points, the patient is considered to have many symptoms (due to shortness of breath, he walks slower than people of the same age).

Rare exacerbations - no more than one moderate exacerbation of COPD over the past year, frequent exacerbations - 2 or more exacerbations, or 1 or more hospitalizations associated with exacerbations of COPD. It is important to note that patients' understanding of the term "exacerbation" is low: 59.2% have never heard this term/do not know what it means.

Thus, a comprehensive assessment of COPD consists of the following components: spirometry: confirmation of the diagnosis (post-BD Tiffno determination), assessment of flow limitation (FEV1 determination), assessment of symptoms/risk of exacerbations (ABCD).

To assess the clinical response to therapy, we use the following: assessment of the severity of clinical symptoms (shortness of breath scale, CAT test), frequency and nature of exacerbations, presence of hospitalizations for COPD, frequency of use of short-acting bronchodilators, adherence to therapy, presence of side effects; checking inhalation technique, determining exercise tolerance.

Next, we assess physical activity in a patient with COPD: dyspnea scales (mMRC, Borg, TDI), 6-minute walk test, shuttle test, dynamometry, cardiorespiratory test, patient interview.

The 6-minute walk test is the most common exercise test, which is used to determine the exercise tolerance of patients with respiratory pathologies, assess the prognosis of the disease and the effectiveness of therapy. An important aspect is predicting the mortality of patients with COPD, that is, reducing this distance to less than 289 m increases the risk of death by 2 times.

Methodology for conducting the 6-minute walk test: the task is to walk along a 30 m long corridor as far as possible in 6 minutes at your own pace; before the start and at the end of the study, shortness of breath is assessed on a special scale, examining heart rate and oxygen saturation, after 6 minutes The walking distance with turns is measured (in meters), using this figure the severity of the disease is determined, the effectiveness of treatment is assessed and indications for oxygen therapy are determined.

Differential diagnosis:

Bronchial asthma (risk factors in the form of allergens, family history, onset at a young age most often, undulation and brightness of clinical manifestations, their reversibility).

Bronchiectasis (large amounts of purulent sputum, frequent relapses of bacterial respiratory infections, rough dry rales of varying tempos and varying sizes of moist rales during auscultation, CT scan: dilatation of the bronchi and thickening of their walls).

Tuberculosis (onset at any age, characteristic radiological signs, microbiological confirmation, epidemiological signs (high prevalence of tuberculosis in the region).

Bronchiolitis obliterans (onset at a young age in non-smokers, an indication of rheumatoid polyarthritis or acute exposure to harmful gases, CT reveals areas of low density during exhalation).

CHF (corresponding cardiac history, characteristic wheezing on auscultation in the basal regions, radiography - expansion of the heart shadow and signs of pulmonary tissue edema, spirometry - predominance of restriction).

It is important to distinguish between COPD and age-related involutive changes in the lungs, and these changes are often combined with each other. The main differences from COPD are that with aging there are no changes at the level of terminal bronchioles and arterial pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale do not develop.

The diagnosis of COPD should include; severity, severity of clinical symptoms, frequency of exacerbations, phenotype of COPD, complications, concomitant diseases.

The treatment of COPD includes the treatment of stable COPD and the treatment of exacerbations.

Pharmacotherapy tactics for stable COPD include non-drug therapy (smoking cessation, training in inhalation techniques and basic self-control, vaccination against influenza and pneumococcal infection, encouragement to physical activity, treatment of concomitant diseases, short-acting bronchodilators to relieve symptoms, assessment of the need for respiratory oxygen therapy and mechanical ventilation) and drug therapy. For mild symptoms, we can start with initial monotherapy (LAMA or LABA), if symptoms persist, we carry out two-component therapy (LAMA/LABA), if there is no effect - ICS/LABA, if symptoms persist - LAMA/LABA/ICS. If this therapy does not help, we carry out phenotyping and prescribe phenotype-specific therapy (roflumilast, mucoactive drugs, macrolides, etc.).

As for e-cigarettes, researchers have proven that e-cigarettes are associated with the development of acute lung injury, eosinophilic pneumonia, alveolar hemorrhage, bronchiolitis and other forms of pulmonary disorders. The disease can only be stopped by completely stopping smoking.

The rehabilitation program for COPD includes psychological and physical rehabilitation in the form of physical therapy and breathing exercises.

Physiotherapy is also used, which has an anti-inflammatory effect, accelerates the resorption of the inflammatory infiltrate, helps improve pulmonary ventilation and drainage function, and improves the patient’s quality of life.

Pharmacological classes of drugs are represented by bronchodilators (CDBA, LABA), anticholinergic drugs (CDAC, DDAC), corticosteroids, phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors, theophylline. At the same time, bronchodilators more effectively reduce shortness of breath, and M-anticholinergics better reduce the risk of exacerbations and reduce sputum production.

Fixed (“closed”) combinations of DCB/LABA:

1 time per day: indacaterol/glycopyrronium bromide (Ultibra), olodaterol/tiotropium bromide (Spiolto), vilanterol/umeclidium bromide (Anoro).

2 times a day: formoterol/aclidinium bromide, formoterol fumarate/glycopyrrolate.

ICS are not prescribed as initial therapy. Unreasonable use of triple therapy should be avoided. It is possible to cancel ICS prescribed without indications.

Indications for the use of ICS:

- Frequent exacerbations (more than 2 moderate exacerbations within 1 year or more than 1 severe exacerbation requiring hospitalization).

- Combination of COPD and asthma.

- Eosinophilic inflammation (increased eosinophil content in sputum, more than 2-3% of the total number of cells) or in the blood (more than 300 cells in 1 μl) without exacerbation.

ICS can be used as part of either double (LABA/ICS) or triple (LABA, LABA, ICS) therapy.

ICS for COPD increases the risk of pneumonia, osteoporosis and fractures, diabetes, cataracts and glaucoma).

Situations when the use of ICS should be avoided in COPD: severe emphysema, decreased body mass index, elderly patients, patients with a history of pneumonia.

Indications for discontinuation of ICS-containing therapy: non-compliance with modern recommendations, risk of side effects, possibility of transferring the patient to a fixed combination of LABA/LAMA.

Treatment for exacerbation:

- Bronchodilators (SABA)

- Systemic corticosteroids (prednisolone 30-40 mg/day for 5-7 days, safer than inhaled corticosteroids).

- Antibacterial treatment (depending on the group of patients with COPD).

Potential causes of exacerbations: infection, environmental pollutants, poor adherence to drug therapy, concomitant CVD, suppression of respiratory function due to improper use of sedatives.

New algorithm for COPD therapy: key changes:

- Long-acting bronchodilators (LAMA, LABA, or combination LAMA/LABA) are indicated in all patients with COPD.

- For patients with severe symptoms, a combination of LAMA/LABA is indicated from the start of therapy.

- ICS are not prescribed as initial therapy. Unreasonable use of triple therapy (LAMA/LABA/ICS) should be avoided.

- It is possible to cancel the prescribed ICS.

Assessing the need to change current therapy

- 3 months – depending on the severity of symptoms.

- From 6 months – stability of the course of exacerbations.

Conclusion:

Our main goal is to achieve control of COPD management in the form of a low impact of symptoms and stability of the course with a low frequency of exacerbations.

List of used literature:

- Global strategy for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Revision 2021

3. Treatment for exacerbation of the disease

A COPD flare, or exacerbation, means that the symptoms of the disease - cough, shortness of breath, mucus production in the lungs - suddenly and rapidly worsen. You can cope with an attack of COPD both in a hospital, under the supervision of a doctor, and at home, if you are not able to immediately get to the clinic. Either way, it's worth knowing that a COPD attack can be potentially life-threatening.

, therefore, it is better to immediately consult a doctor and, if possible, only then continue treatment at home.

medications may be used to treat exacerbations of COPD

– anticholinergics, oral corticosteroids, beta-2 agonists, phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors.

In addition, artificial lung ventilation devices

.

They are needed if medications do not help cope with an attack of COPD, and the patient’s condition worsens. There are two types of ventilation.

positive pressure

ventilation In invasive ventilation,

a breathing tube is inserted into the trachea, through which a machine supplies air to the lungs. Oxygen therapy is a less serious measure, but it will also help breathing.

A course of antibiotics is sometimes prescribed to treat COPD

. These medications are needed when there is reason to suspect a bacterial infection in patients with COPD. An infectious disease often causes exacerbation of COPD, so it is important to diagnose and treat it in a timely manner.

About our clinic Chistye Prudy metro station Medintercom page!