28.06.2017

Diseases of the chest and abdominal cavity | Liver and pancreas

The starting point for the departure of bile is the place of its formation - liver cells. The final point is the duodenum, where bile carries out its main work. Between them are transport routes of varying lengths and calibers, passing both inside and outside the liver. They are called bile ducts or vessels. In ancient Greek, “χολή” means bile and “ἀγγεῖον” means vessel. Hence the accepted name for their inflammation - cholangitis.

Causes and types

Cholangitis occurs due to obstruction of the bile ducts and associated infection. The patency of the ducts can be difficult due to the formation of stones, scarring, removal of the gallbladder, cysts, various parasites, etc.

Infection usually occurs in two ways:

- ascending route (from the intestine);

- descending path (through blood and lymph).

- There are acute and chronic cholangitis.

In this case, acute cholangitis occurs:

- catarrhal (with the occurrence of swelling of the mucous membrane of the bile ducts);

- purulent (pus forms and spreads to neighboring organs);

- diphtheritic (necrosis occurs during inflammation);

- necrotic (occurs due to the entry of enzymes into the pancreas, destroying the mucous membrane);

- The chronic form can be latent, recurrent, septic, abscessing, sclerosing.

The first case of this disease was described more than 100 years ago. RVS is 10 times more common in women than men and is the most common reason for liver transplantation in women. The peak incidence occurs between 50 and 70 years of age. There are no cases described in children with the classic clinical picture of the disease. The youngest age of a patient with RVS described in the literature is 15 years. According to a review of epidemiological studies in Europe, North America, Asia and Australia, the prevalence of RVS ranges from 0.6 to 40 cases per 100 thousand inhabitants, and 92% of cases are women.

Etiopathogenesis

The pathogenesis of RVS remains unknown. The exact cause of disease underlying damage to intrahepatic biliary epithelial cells leading to cholestasis, fibrosis, and biliary cirrhosis remains unclear but is likely multifactorial, including genetic predisposition and environmental triggers. Various studies have consistently found a link between RVS and urinary tract infections caused by E. coli. Another bacterium that may be involved in the etiology of RVS through cross-reactivity is Novosphingobium aromaticivorans. Case-control studies analyzing various lifestyle factors of patients with RVS have shown an association of increased susceptibility to RVS with chemicals commonly used in everyday life, such as nail polish, hair dye, smoking, and toxic waste.

PBC has a strong genetic basis, with a higher risk of development among relatives than most other autoimmune diseases. The relative risk for a first-degree relative is 50 to 100 times higher than for the general population. A study conducted in the United States showed an increased incidence of antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) without any evidence of disease in first-degree relatives and descendants of patients with RVS, which indirectly indicates the presence of a strong genetic predisposition to this disease.

Clinic

The clinical picture of RVS at the onset of the disease is scarce. The disease can be asymptomatic for a long time, with only an increase in the level of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in the blood serum, and be detected by chance during a routine examination for other diseases.

Key symptoms reported by patients are fatigue and itchy skin. Other complaints may be present in the form of dysphagia, dry mucous membranes, and the appearance of calcifications in the skin. In 30% of patients, the disease progresses with the development of cirrhosis and associated complications, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Objective data during examination are usually absent, but the appearance of xanthomas and xanthelasmas, vascular stigmata, hepato- and splenomegaly is possible.

Diagnostics

The disease occurs with an increase in cholestasis enzymes - alkaline phosphatase and g-glutamyltransferase (GGT). However, it should be remembered that ALP can enter the blood serum from various sources (liver, small intestine, bones, placenta). An increase in its serum level is observed not only with cholestatic liver diseases, but also with rapid bone growth in children, extrahepatic diseases (for example, Paget's disease), vitamin D deficiency, and pregnancy. Hyperlipidemia is also common in RVS.

The serological hallmark of PBC is the presence of high titer AMA in the blood serum, as well as elevated IgM and several disease-specific antinuclear antibodies (ANA).

The most disease-specific autoantibodies, which are detected in 90–95% of patients with RVS, are AMA, whose titer of 1:40 or higher is considered positive. However, the level of antibody titer does not correlate with the severity of the disease. AMA can also be detected in bile, urine, and saliva in PBC. The extremely high sensitivity and specificity of AMAs make them one of the most specific diagnostic tests for RVS. AMA often continues to be detected after liver transplantation.

Other autoantibodies that are identified in patients with RVS are ANA: anti-Sp100 and anti-gp210 are detected in approximately one third of sera from patients with RVS and are markers of a more severe and rapidly progressive course of the disease. Their determination has diagnostic value in AMA-negative patients.

RVS does not cause morphological changes in the liver that can be visualized. Instrumental studies such as ultrasound, magnetic resonance, and radiation are used to exclude mechanical obstruction of the biliary tract, space-occupying formations, including extrahepatic ones, and gallbladder diseases.

Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing RVS. Histologically, RVS manifests itself as a chronic non-suppurative destructive cholangitis with the formation of granulomas in the liver, degeneration and necrosis of biliary epithelial cells and the disappearance of small or medium-sized intrahepatic bile ducts.

Given the high specificity of serological markers, a biopsy to confirm the diagnosis of RVS is not necessary. The need for it arises only in the absence of antibodies specific for RVS or suspicion of concomitant autoimmune hepatitis or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, in the presence of systemic or extrahepatic concomitant diseases. Biopsy can also be informative for the qualitative and quantitative assessment of histological changes in patients without an adequate response to standard therapy.

In order to assess the degree of fibrosis in RVS, according to modern recommendations, liver elastometry is used.

The diagnosis of RVS is established on the basis of clinical criteria, an increase in the level of ALP more than two norms or GGTP more than five norms (for at least six months), the presence of serum AMA (titer ≥1:40) and a characteristic histological picture of the liver with “blooming” damage to the biliary ducts

Liver biopsy is not necessary in the presence of the previous criteria, but it assesses disease activity and stage and is therefore necessary for diagnosis in the absence of specific autoantibodies. Serum AMAs may precede disease onset by several years, but individuals who are found to have only positive AMAs in the absence of other criteria eventually develop RVS during the follow-up period.

Treatment

Current guidelines recommend that the first-line treatment for RVS is ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) at a dose of 13–15 mg/kg/day in two divided doses. All patients with RVS and elevated serum ALP levels, even if asymptomatic, should receive UDCA at the recommended dosage for life. One year after the start of treatment, the Paris criteria are used to assess its effectiveness, according to which therapy is effective when the level of serum bilirubin <17 µmol/l, ALP <3 norms, AST <2 norms, or the Barcelona criteria, where a decrease in ALP levels is considered an indicator of effectiveness by 40% or its normalization.

Although UDCA is very well tolerated and may ultimately improve survival without liver transplantation, approximately 40% of patients do not respond to this therapy and are at risk for disease progression. Such patients should be identified at an early stage of the disease, since obeticholic acid (OBCA), which is an agonist of the farnesoid X receptor (FXR), is approved for use in this category by international recommendations. OBCA is indicated in addition to UDCA in case of insufficient response to it or as monotherapy in case of intolerance. It is prescribed at an initial dose of 5 mg per day, followed by an increase to 10 mg if an adequate reduction in alkaline phosphatase or total bilirubin is not achieved within 6 months.

Although studies have demonstrated biochemical improvements with OBCA, the frequency and intensity of pruritus were significantly increased in treatment groups compared with placebo, potentially limiting the use of OBCA. In addition, there is currently no definitive evidence of improved long-term clinical outcomes with the use of OBCA.

The results of individual clinical studies on the use of fibrates and budesonide with a positive effect in PBC have been published, but they are not recommended for use until convincing data on their effectiveness and safety are available.

Symptomatic therapy

For skin itching, rifampicin is used; if it is ineffective, sertraline is used, which international experts recommend as a first-line treatment, despite some shortcomings. In addition, cholestyramine is prescribed.

Patients with RBC are at risk of developing osteoporosis, a disease that reduces bone density and strength, a common complication that affects approximately one in three people. The prevalence of fractures in people with RVS, according to the literature, is 10–20%. For timely diagnosis of this complication, all patients should undergo osteodensitometry when diagnosing RVS and subsequently monitoring the disease. In the presence of osteoporosis, calcium, vitamin D, and bisphosphonates are prescribed.

Cholestasis and decreased secretion of bile acids as a consequence impair fat absorption, but true deficiency of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K) is rarely observed in RVS. In case of their deficiency, retinol, menadione, and tocopherol can be used for replacement therapy.

Cholestasis is also characterized by hyperlipidemia, but, according to EASL recommendations, there is no evidence of an increase in cardiovascular risk in this regard in RVS. With concomitant metabolic syndrome (with high levels of cholesterol, low levels of high-density lipoproteins and high levels of low-density lipoproteins), the indications for prescribing lipid-lowering drugs are assessed individually. RVS is not a contraindication to their use.

In the presence of dry mucous membranes, artificial tears and artificial saliva are used; if refractoriness to this therapy develops, it is recommended to instill pilocarpine 1% into the conjunctival sac, 1-2 drops 2-4 times a day; For vaginal dryness, use moisturizers.

Patients with RVS are advised to eat a normal diet with controlled intake of sodium and protein. The energy requirement is 35–40 kcal/kg/day, and the protein requirement is 1–1.5 g/kg/day.

Liver transplantation

Despite the increasing incidence of RVS, its importance as an indication for liver transplantation (LT) has decreased in recent decades. LT for RVS is carried out according to the same indications as for other diseases, as a rule, with persistent hyperbilirubinemia more than 50 µmol/l, or a MELD score of >15 points, or with persistent itching that is not amenable to drug correction.

In most cases, the prognosis for LT due to RVS is favorable. The five-year survival rate is 80–85%, which is higher than for LT for other diseases.

Relapse of RVS after LT, according to published data, is observed on average in 20% of patients; relapse of RVS rarely leads to graft loss and, according to the literature, does not affect the survival of recipients.

UDCA therapy reduces liver enzyme levels and possibly the relapse rate of RVS, but there is insufficient evidence to support its mandatory use after LT. In practice, UDCA is considered indicated and is usually prescribed when relapse of RVS is suspected. Liver transplant recipients should also receive osteoporosis prophylaxis.

Hepatocellular cancer

It must be remembered that patients with RVS are at risk for hepatocellular cancer. A recently published multicenter prospective study of more than 4,500 patients with RVS in North America and Europe found an incidence of HCC of 3.4 per 1,000 person-years. This study confirmed the importance of such risk factors for HCC in RVS as male gender and insufficient response to UDCA therapy.

Patients with RVS are subject to lifelong active monitoring by a physician. Timely comprehensive treatment allows not only to control the disease, but also to reduce the risk of complications, as well as reduce the need for liver transplantation.

Symptoms

Symptoms of acute cholangitis:

- fever;

- chills;

- increased sweating;

- intense pain in the hypochondrium on the right;

- nausea, vomiting;

- change in skin color and whites of the eyes (they become yellow);

- skin itching.

The chronic form rarely has pronounced symptoms, but the following manifestations are possible:

- periodic fever;

- itching;

- increased fatigue;

- enlargement of the phalanges of the fingers;

- redness of the palms.

Primary inflammation of the biliary tract

Primary cholangitis can affect both intrahepatic and extrahepatic pathways and is a rare disease. This disease is also called sclerosing disease because scarring occurs in the area of the bile ducts, which lose their elasticity. The presence of scar tissue causes narrowing of the bile ducts, which in turn leads to the retention of bile in the ducts inside the liver. Treatment and prevention vary, as does prognosis.

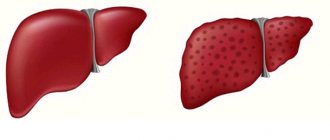

Residual bile destroys liver cells, spreading through the liver ducts, causing cirrhosis and organ failure. The condition of liver cirrhosis is progressive and may be asymptomatic at first, so it is often diagnosed at an advanced stage. In primary cholangitis, liver function gradually deteriorates, leading to serious health consequences.

Cirrhosis of the liver

Treatment

Treatment of cholangitis is possible with both medications and surgery.

Treatment of acute cholangitis is carried out only in a hospital setting due to the risk of complications in the form of spread of infection to other organs.

For conservative treatment, the following is prescribed:

- antibacterial drugs;

- means to combat intoxication;

- drugs aimed at the outflow of bile;

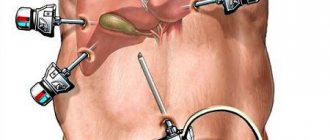

If drug therapy does not produce results, then surgical intervention is indicated. In most cases, the endoscopic technique is used, because it is the least invasive. During the operation, the surgeon can drain the ducts, remove stones, and eliminate narrowing.

In case of extensive lesions, the patient needs strip surgery, during which the destroyed areas are removed.

3.Diagnosis of the disease

First of all, the doctor will examine you and record your symptoms. To accurately diagnose cholangitis, the following methods of examining internal organs can be used:

- Duodenal intubation with bile examination is also performed. This is done to determine the causative agent of cholangitis;

- Ultrasound of the abdominal cavity. Ultrasound helps assess the size of the liver and bile ducts;

- ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography). ERCP allows you to examine the bile ducts X-ray using contrast;

- MRI and CT can complement the results of ERCP.

The following tests are also performed to diagnose cholangitis:

- Complete blood count (CBC). With the help of OAC, inflammatory processes in the body are detected;

- Biochemical blood test (BAC). During the test, the indicators of ALT (alanine aminotransferase), AST (aspartate aminotransferase) and GGT (hamaglutamyl transpeptidase) are measured;

- General urine test for bile pigments;

- Stool analysis for parasites.

About our clinic Chistye Prudy metro station Medintercom page!

How does secondary cholangitis manifest?

Patients with secondary cholangitis may experience:

- heat;

- chills;

- pain in the upper abdomen (right or middle).

High fever

Inflammation of the bile ducts can be very dangerous as it can lead to life-threatening septic shock in some cases. In patients whose inflammation is of bacterial origin, many toxins produced by foreign bodies multiply in the body. Sepsis not only causes life-threatening complications, but also significantly impairs the functioning of vital organs. Any untreated septic shock will result in death!

How to treat cholangitis?

Treatment is based primarily on proper nutrition. Patients hospitalized for secondary cholangitis are rehydrated using drip irrigation. In addition, they are given antibiotics.

Some patients may require surgical treatment with ERCP to dilate the bile ducts.

ONLINE REGISTRATION at the DIANA clinic

You can sign up by calling the toll-free phone number 8-800-707-15-60 or filling out the contact form. In this case, we will contact you ourselves.

If you find an error, please select a piece of text and press Ctrl+Enter