General information

Duodeno-gastric reflux (syn. reflux gastritis , biliary reflux , alkaline gastritis , biliary gastritis ) is a pathological process of retrograde flow of bile contents of the duodenal intestine into the stomach, which can be accompanied by clinical symptoms, histological signs and endoscopic changes of reactive (chemical) gastritis.

The term "refluxus" means "reverse flow". Under physiological conditions, bile from the duodenum should not enter the anatomically overlying parts of the digestive canal, therefore the bile reflex is considered a pathological phenomenon. DGR occurs as a result of excessive flow of bile from the duodenum due to insufficiency of the pylorus, which acts as a barrier to the retrograde flow of bile or due to a violation (reduction) of anterograde peristalsis of the stomach and duodenum. Modern scientific research indicates an increase in the number of diseases caused by the presence of pathological duodenogastric reflux in patients. At the same time, the high prevalence of GHD (in 46-52% of cases) and the frequent combination with chronic gastritis , functional dyspepsia , peptic , GERD , stomach cancer , Barrett's esophagus , sphincter of Oddi dysfunction , duodenostasis , postcholecystectomy syndrome , etc. complicates their course and therapy. GHD is quite common after surgery (in 16% of cases after cholecystectomy and in almost 55% of cases after surgery for duodenal ulcers).

In addition, duodenal reflux can cause the development of metaplasia of the esophageal epithelium, severe esophagitis and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus against the background of metaplasia. It should be noted that gastroduodenal reflux in its “pure” form (positioned as an isolated diagnosis) is relatively rare (10-15%) and is mainly diagnosed against the background of other diseases. That is, in most cases, GHD is a syndrome accompanying a number of diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract.

GHD occurs due to excessive flow of bile from the duodenum due to insufficiency of the pylorus, which acts as a barrier to the retrograde flow of bile or due to a violation (reduction) of anterograde peristalsis of the stomach and duodenum.

Thus, duodenal pathological reflux complicates the course of various organic/functional diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, which necessitates its timely diagnosis, correct clinical interpretation and adequate drug correction.

Advantages of treatment of duodeno-gastric reflux at the Swiss University Hospital

- Our Center is equipped with modern equipment produced by leading European and American companies, which allows us to carry out the most complex diagnostic and therapeutic procedures with high accuracy and efficiency.

- The clinic employs specialists of the highest and first categories who have extensive experience; each of them is fluent in all techniques in their specialization.

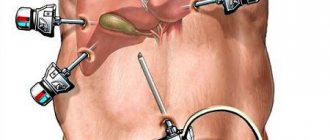

- Our specialists have performed more than 600 surgical interventions related to duodenal obstruction.

- Patients who have concomitant diseases of the abdominal cavity and pelvis and require surgical treatment can undergo simultaneous surgery in our clinic. During one intervention, you can get rid of 3-4 pathologies (for example, kidney cysts, ovarian cysts, nephroptosis, fibroids and a number of other diseases).

Pathogenesis

The pathogenetic mechanisms of development of GDR are based on:

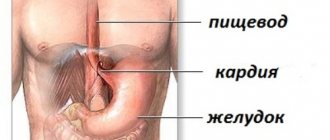

- failure of the sphincter apparatus, which allows the contents of the duodenal intestine to freely reach the stomach through the pyloric/lower esophageal sphincters;

- antroduodenal dysmotility (disorder of coordination between the pyloric/antral parts of the stomach and duodenal intestine), which leads to disruption of control over the direction of flow of duodenal contents;

- elimination of the antireflux barrier after surgery (partial gastrectomy ).

With the development of pathological GHD due to dysfunction of the sphincters, bile retrogradely, as part of the refluxate, enters from the duodenum into the higher located stomach. Components of duodenal contents, represented by bile acids, lysolecithin and trypsin , have an aggressive damaging effect on the gastric mucosa. Taurine conjugated bile acids and lysolecithin have the most pronounced effect, especially at acidic pH, which determines their synergy with hydrochloric acid in the development of gastritis . Trypsin and non-conjugated bile acids have a pronounced toxic effect at slightly alkaline and neutral pH, while the toxicity of non-conjugated bile acids is provided predominantly by ionized forms that can easily penetrate the coolant.

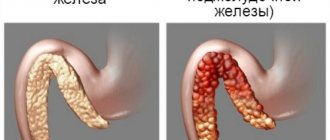

Long-term exposure of the coolant to bile acids contained in bile causes necrobiotic and dystrophic changes in the surface epithelium and leads to the condition of reflux gastritis (gastritis C).

In the presence of Helicobacter pylori, the damaging effect of the refluxant on the coolant is enhanced. The formation of DGR contributes to disruption of the motility of various parts of the gastrointestinal tract and the function of the sphincters, which leads to disruption of the digestive conveyor, has a negative effect on membrane/cavity digestion and absorption of food ingredients, and changes the water balance. The aggressive influence initially manifests itself in the form of increasing atrophy, dysplasia and metaplasia of the coolant, which form the risk of developing gastrocarcinogenesis. The gradual aggressive effect of bile with pancreatic juice contributes to the fact that superficial gastritis progresses and mucosal erosions transform into erosive and ulcerative lesions of the coolant.

Approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of gastritis associated with bile reflux

The wide distribution of reflux gastritis in clinical practice in the absence of a single term [2] (synonyms: gastritis type C, alkaline gastritis, reactive gastropathy), as well as an understanding of the mechanisms of formation, standards of diagnosis and therapy make it relevant to analyze and highlight the existing ideas about this variant of gastritis .

Gastritis associated with biliary reflux (Latin refluo - to flow backwards) is rarely primary in nature [2, 3], mainly developing secondary to anatomical changes associated with surgery: gastric resection, gastroenterostomy, enterostomy, vagotomy, cholecystectomy. Failure of the sphincter apparatus, antroduodenal discoordination (impaired coordination between the antral, pyloric parts of the stomach and the duodenum), as well as resection of part of the stomach, leading to the elimination of the natural anti-reflux barrier, are the cause of the formation of recurrent reflux of duodenal contents containing bile into the stomach with damage to it mucous membrane.

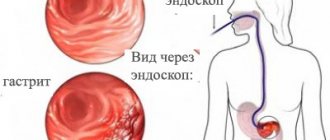

Any diagnostic process begins with a survey and medical history. In the presence of symptoms of dyspepsia, which are not specific in nature and in some cases of reflux gastritis may be absent, as well as in diseases and conditions that have a high risk of biliary reflux (cholelithiasis, conditions after gastric resection, vagotomy, etc.), It is necessary to conduct an endoscopic examination with a biopsy of the gastric mucosa to determine the presence, degree and stage of gastritis, as well as Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection.

The endoscopic picture of reflux gastritis is characterized by hyperemia and swelling of the mucous membrane, which spread circularly from the pylorus in the proximal direction. At the same time, bile stains are often found on it, there is a visible reflux of bile from the duodenum into the stomach or a high content of bile in the lumen of the stomach.

There is no “gold standard” for diagnosing duodenogastric reflux yet. As a method of functional diagnostics, 24-hour pH-metry, fluoroscopy and ultrasound examination of the stomach are used. The main method for diagnosing biliary reflux is currently the pH-monitoring system Bilitec 2000, which quite qualitatively assesses bile reflux and pH in the stomach. Barrett MW et al [4] showed the high sensitivity of this device for monitoring bile reflux in vivo, but somewhat lower in vitro, with a false-negative rate of about 23%. In acidic conditions, the amount of bilirubin absorption determined by this device decreases, which can lead to an increase in false negative results and, accordingly, a decrease in false positive results. Although this method cannot be classified as the “gold standard” for duodenogastric reflux, it is the most convenient and usable for dynamic monitoring of bile reflux [5].

Why is reflux of duodenal contents into the stomach dangerous, what structural changes occur in the gastric mucosa under the influence of duodenal refluxate?

It is known that bile acids, which have detergent properties, promote the solubilization of lipids in the membranes of the surface epithelium, while their negative effect on the epithelium depends on their concentration, conjugation and pH of the environment, as well as on the length of time during which the mucous membrane is exposed to bile [6]. At low pH values, only taurine conjugates damage the mucous membrane, and at high pH values (for example, in the gastric stump after surgery), it is unconjugated bile acids that have a negative effect. In addition to the bile acids themselves, lysolecithin, formed under the influence of pancreatic phospholipase A from lecithin, has a damaging effect, with an increase in the reverse diffusion of hydrogen ions, as well as an increase in the release of histamine and gastrin. In recent years, the possible interaction of bile acids with a certain subtype of muscarinic receptors localized on chief cells has been discussed, as a result of which active inflammation, gland atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and focal hyperplasia develop in the gastric mucosa [7].

In addition, bile reflux, changing the chemical composition of the surface of the mucous membrane, can potentiate the action of other pathogenic factors: infections of HP and gastric juice [8, 9]. Chen SL et al [10], assessing the effect of biliary reflux on the severity of damage to the gastric mucosa in 49 patients with dyspepsia and chronic gastritis, did not establish a relationship between the duration of duodenal reflux and pH in the gastric cavity, which indicates the presence of complex feedback mechanisms, including regulation of the secretory and evacuation functions of the stomach. At the same time, the degree of changes in the mucous membrane, as well as colonization with HP infection, correlated with the duration of biliary reflux. Moreover, the data obtained clearly demonstrated the relationship between biliary reflux and the severity of damage to the gastric mucosa. Thus, severe reflux correlated with active inflammation (r = 0.3949, P < 0.05), chronic inflammation (r = 0.8938, P = 0.0001), mucosal atrophy (r = 0.4619, P < 0.005 ) and HP colonization in the body of the stomach (r = 0.8938, P = 0.0001). In this work, as in some others [11], the cumulative pathogenic effect of HP infection and biliary reflux on the gastric mucosa was demonstrated. One can assume a complex mechanism for this effect. Thus, the absorption of bile refluxant on the surface of the gastric mucosa has a direct damaging effect, and also enhances the effect of pepsin and hydrochloric acid; damage to the mucous membrane, in turn, contributes to the colonization of HP from the antrum to the body of the stomach. In the absence of infection of HP due to the reflux of alkaline contents from the duodenum and changes in pH, bacterial contamination by the microflora of the underlying parts of the digestive tract is possible, which also leads to more pronounced damage to the gastric mucosa.

The characteristic morphological signs of this variant of gastric damage include the phenomenon of foveal hyperplasia, proliferation of smooth muscle cells in the lamina propria, as well as changes in the production of mucins by mucocytes, which play an important role in the protection of the mucous membrane [12] (Fig.). Modification of secreted mucins, detected immunohistochemically, leads to reactive/regenerative changes similar to the manifestations of gastropathy caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID gastropathy) [13]: the expression of membrane mucin (MUC1), which is involved in the processes of adhesion and polarity, and secretory mucins (MUC5AC and MUC6). The detected changes differ from HP-associated gastritis, in which the expression of MUC5AC on the surface epithelium decreases, and the MUC6 mucin spreads to the surface of mucocytes [14].

In prognostic terms, another aspect of changes in the gastric mucosa associated with biliary reflux is also extremely important. Persistence of inflammation with hyperproduction of free radicals, impaired microcirculation and, as a consequence, impaired cellular renewal processes leads to a more frequent occurrence of atrophy and intestinal metaplasia of the gastric mucosa compared to a similar age population. It is appropriate here to recall the higher risk of developing intestinal cancer in the gastric stump, which has been demonstrated in both experimental and epidemiological studies [15, 16].

Of course, the presence and severity of the inflammatory infiltrate, as well as atrophy of the gastric mucosa, do not determine whether the patient has clinical symptoms of dyspepsia resulting from disorders of gastric secretion, gastroduodenal motility, and visceral sensitivity. Why, then, is it so important for a clinician to adequately interpret the pathologist’s findings? The answer lies in the goals of the gastritis classification system - to assess the condition of the mucous membrane, characterize the inflammatory process for prognosis and personalize the patient’s observation program, primarily to prevent the progression of inflammatory changes and the development of atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, dys/neoplasia.

A thorough analysis of the dyspepsia syndrome, data from endoscopic, biopsy and functional studies, carried out by the clinician, creates the basis for the formation of treatment goals for the patient:

- relieve manifestations of dyspepsia (if any) to improve the patient’s quality of life;

- reduce changes in the mucous membrane to prevent the formation of atrophy with intestinal metaplasia, and if they are present, stop the progression of changes in the mucous membrane to prevent stomach cancer.

An important component of the treatment program should be the modification of the patient’s lifestyle and diet. Timely intake of food, the absence of excess animal fats and sweet carbonated drinks in the diet, cessation of smoking and alcohol intake contribute to positive changes in the course of gastritis with dyspepsia syndrome.

If HP infection is present, eradication therapy should be planned to eliminate an additional factor that damages the gastric mucosa and increases the risk of recurrence of dyspepsia syndrome.

Since motor disorders occupy a key position in the formation of reflux gastritis, it is advisable to prescribe prokinetics (Ganaton, Trimedat) as one of the means of pathogenetic therapy. However, only by prescribing drugs of this group it is impossible to achieve all the goals of therapy for reflux gastritis.

The next group of pathogenetic therapy agents, rational for a number of patients with cholelithiasis, functional disorders of the biliary tract, and concomitant chronic diffuse liver diseases, are ursodeoxycholic acid preparations (Ursosan, Ursofalk, Urdoxa, Ursodex), which are prescribed in a daily dose of 10–13 mcg /kg of weight in courses of 6-8 weeks, and if necessary - for a longer period.

The classic conservative approach to the treatment of gastritis associated with biliary reflux is the administration of antacids and bismuth salts. In one well-designed study, the use of sucralfate and rabeprazole in patients with biliary reflux after cholecystectomy demonstrated its effectiveness on both clinical manifestations and the severity of macroscopic signs of inflammation diagnosed by endoscopic examination [17].

Thus, the appointment of a course of therapy with prokinetics, antisecretory agents and mucocytoprotectors makes it possible to relieve the symptoms of dyspepsia. It is also possible to reduce changes in the mucous membrane in order to prevent the development of atrophy with intestinal metaplasia, and if they are present, to stop the progression of changes in the mucous membrane for the prevention of stomach cancer as a result of including muco/cytoprotectors in therapy.

The group of muco/cytoprotectors includes several drugs (table), among which the therapeutic capabilities of bismuth salts, including De-Nol, should be separately highlighted. Numerous studies have shown that bismuth preparations form a protective layer on the affected areas of the mucous membrane, protecting it from the effects of aggressive factors, stimulate the secretion of mucus and bicarbonate, inhibit the activity of pepsin, protect epithelial growth factors from decay, promoting the regeneration of epithelial cells, improve microcirculation, stimulate secretion of gastroprotective prostaglandins. Along with the cytoprotective effects listed above, two factors should be mentioned separately. This is the bactericidal effect of De-Nol against Helicobacter and the ability of De-Nol to bind bile acids [26]. Helicobacter eradication using a four-component regimen, including De-Nol, significantly reduces the severity of duodenogastric reflux, which was convincingly shown in a study by SD Ladas et al. [27]. Neutralization of bile acids and their salts is also extremely important in terms of eliminating one of the leading pathogenetic factors of reflux gastritis. Considering the above, the use of De-Nol for gastritis caused by duodenogastric reflux is absolutely justified from a pathogenetic point of view.

Under conditions of contamination of the gastric mucosa with non-NR microorganisms [18], including Helicobacter spp. [19], Proteus mirabilis, Citrobacter freundii, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae, Staphylococcus aureus, with an additional stimulus for the persistence of the inflammatory infiltrate, activation of lipid peroxidation processes and the production of nitrosamines by bacteria, which have pro-carcinogenic potential [20], it is also important for the clinician to use the effects of salts bismuth. Firstly, not being an antibiotic, De-Nol suppresses the activity of bacterial flora without the risk of developing resistance, which has been successfully used for many years in standard eradication therapy. Secondly, in conditions of persistent inflammation, the properties of De-Nol that affect the activity of the inflammatory process become necessary, namely a decrease in the content of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the presence of an antioxidant effect. It should be noted that these properties of the drug are successfully used in the treatment of other diseases, including intestines. Thirdly, patients with reflux gastritis, especially with atrophy, especially need mucocytoprotective therapy with increased production of mucus, prostaglandins, and improved microcirculation in the gastric mucosa [25].

Finally, attempts are being made to correct the negative impact of reflux using surgical methods [21] (entero-enteroanastomosis according to Brown, Roux-en-Y), especially after gastrectomy as a “reserve” if all other methods of therapy have been ineffective.

Thus, gastritis associated with bile reflux, despite the lack of diagnostic and treatment standards, can be detected in a timely manner using an integrated approach and there are quite reliable, safe and effective drugs for its treatment.

Literature

- Kawiorski W., Herman RM, Legutko J. Current diagnosis of gastroduodenal reflux and biliary gastritis // Przegl Lek. 2001; 58:90–94.

- Hermans D., Sokal EM, Collard JM, Romagnoli R., Buts JP Primary duodenogastric reflux in children and adolescents // Eur J Pediatr. 2003, Sep; 162(9):598–602. Epub 2003, Jun 26.

- Lin JK, Hu PJ, Li CJ, Zeng ZR, Zhang XG A study of diagnosis of primary biliary reflux gastritis // Zhonghua Neike Zazhi. 2003; 42:81–83.

- Barrett MW, Myers JC, Watson DI, Jamieson GG Detection of bile reflux: in vivo validation of the Bilitec fibreoptic system // Dis Esophagus. 2000; 13:44–45.

- Barrett MW, Myers JC, Watson DI, Jamieson GG Dietary interference with the use of Bilitec to assess bile reflux // Dis Esophagus. 1999; 12:60–64.

- Stathopoulos P., Zundt B., Spelsberg FW, Kolligs L., Diebold J., Goke B., Jungst D. Relation of gallbladder function and Helicobacter pylori infection to gastric mucosa inflammation in patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis // Digestion. 2006; 73 (2–3): 69–74.

- Raufman JP, Cheng K., Zimniak P. Activation of muscarinic receptor signaling by bile acids: physiological and medical implications // Dig Dis Sci. 2003; 48:1431–1444.

- Chen SL, Mo JZ, Chen XY, Xiao SD The influence of bile reflux, gastric acid and Helicobacter pylori infection on gastric mucosal injury: Severity and localization // Weichang Bingxue. 2002; 7: 280–285x.

- Johannesson KA, Hammar E., Stael von Holstein C. Mucosal changes in the gastric remnant: long-term effects of bile reflux diversion and Helicobacter pylori infection // Eur. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003; 15:35–40.

- Chen SL, Mo JZ, Cao ZJ, Chen XY, Xiao SD Effects of bile reflux on gastric mucosal lesions in patients with dyspepsia or chronic gastritis // World J Gastroenterol. 2005. May 14; 11(18):2834–2847.

- Abe H., Murakami K., Satoh S., Sato R., Kodama M., Arita T., Fujioka T. Influence of bile reflux and Helicobacter pylori infection on gastritis in the remnant gastric mucosa after distal gastrectomy // J Gastroenterol. 2005, Jun; 40(6):563–569.

- Mino-Kenudson M., Tomita S., Lauwers GY Mucin expression in reactive gastropathy: an immunohistochemical analysis // Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007, Jan; 131(1):86–90.

- Mino-Kenudson M., Tomita S., Lauwers GY Mucin expression in reactive gastropathy: an immunohistochemical analysis // Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007, Jan; 131(1):86–90.

- Corfield AP, Myerscough N., Longman R., Sylvester P., Arul S., Pignatelli M. Mucins and mucosal protection in the gastrointestinal tract: new prospects for mucins in the pathology of gastrointestinal disease // Gut. 2000. 47: 589–594.

- Ma Z., Wang Z., Zhang J. Carcinogenicity of duodenogastric reflux juice in patients undergoing gastrectomy // Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2001, Oct; 39(10):764–766.

- Oba M., Miwa K., Fujimura T., Harada S., Sasaki S., Hattori T. Chemoprevention of glandular stomach carcinogenesis through duodenogastric reflux in rats by a COX-2 inhibitor // Int J Cancer. 2008, Oct 1; 123(7):1491–1498.

- Santarelli L., Gabrielli M., Candelli M., Cremonini F., Nista EC, Cammarota G., Gasbarrini G., Gasbarrini A. Post-cholecystectomy alkaline reactive gastritis: a randomized trial comparing sucralfate versus rabeprazole or no treatment // Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003, Sep; 15(9):975–979.

- Takako Osaki, Katsuhiro Mabe, Tomoko Hanawa, Shigeru Kamiya. Urease-positive bacteria in the stomach induce a false-positive reaction in a urea breath test for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection // Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2008, 57, 814–819.

- Cinthia G. Goldman and Hazel M. Mitchell. Helicobacter spp. other than Helicobacter pylori 2010 Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Helicobacter 15(Suppl. 1): 69–75.

- Correa P. A human model of gastric carcinogenesis // Cancer Res. 1988; 48:3554–3560.

- Madura JA Primary bile reflux gastritis: diagnosis and surgical treatment // Am J Surg. 2003, Sep; 186(3):269–273.

- Slomiany V. L., Nishikawa H., BHski J., Slomiany A. Colloidal bismuth subcitrate inhibits peptic degradation of gastric mucosa_epidermal grown factor in vitro // Amer. J. Gastroenterol. 1990. V. 85. P. 390–393.

- Lambert JR, McLean. Pharmacology of colloidal bismuth subcitrate (De-Nol) and use in non ulcer dyspepsia / Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulceration and gastritis; eds. B. J. Marshall, R. W. McCallum, R. L. Guerrant. Oxford, London, Edinburgh, Melbourne: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1991, pp. 201–209.

- Kononov A.V. Cytoprotection of the gastric mucosa: molecular cellular mechanisms // Russian Journal of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Coloproctology. 2006. No. 3. pp. 12–16.

- O'Connor A., Gisbert JP, McNamara, O'Morain C. Treatment Of Helicobacter pylori Infection 2011 // Helicobacter. 2011. Sep. 16:53–58.

- Wagstaff AJ, Benfield P, Monk JP Colloidal bismuth subcitrate. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and its therapeutic use in peptic ulcer disease // Drugs. 1988; 36: 132–157.ha

- Ladas SD, Katsogridakis J., Malamou H. et al. Helicobacter pylori may induce bile reflux: link between H. pylori and bile induced injury to gastric epithelium // Gut. 1996; 38: 15–18.

M. F. Osipenko*, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M. A. Livzan**, Doctor of Medical Sciences

* State Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Novosibirsk State Medical University of the Ministry of Health and Social Development of Russia", Novosibirsk ** State Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education "Omsk State Medical Academy of the Ministry of Health and Social Development of Russia", Omsk

Contact information for authors for correspondence

Causes

The main reasons for the formation of DGR include:

- Congenital/acquired functional deficiency (weakening of the closing function) of the pyloric sphincter.

- Hyperkinetic type (with increased motility) of duodenal peristalsis.

- Inconsistency (discoordination) of the physiological cycles of relaxation/contraction of both the stomach and the DP-gut (migrating motor complex).

- Duodenal hypertension (increased pressure in the lumen of the duodenum), caused by splanchnoptosis (prolapse of internal organs), lumbar lordosis , hernias /malignant neoplasms.

- Long-term inflammation of the duodenum (chronic duodenitis , duodenal ulcer , gastroduodenitis ).

- Lack/absence of hormones ( gastrin ).

- Helminthic infestation (giardiasis).

- Anomalies in the development of the duodenal intestine.

Risk factors for developing duodenogastric reflux include:

- irregular food intake and poor quality nutrition (overeating, dry food, fatty and spicy foods that cause hypersecretion of bile);

- smoking and alcohol abuse;

- old age (after 60 years);

- long-term use of antispasmodics and NSAIDs;

- operations for resection of part of the stomach, cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder), anastomosis of the intestine and stomach;

- biliary dyskinesia , cholecystitis ;

- pancreatitis;

- diabetes mellitus , obesity .

Symptoms

Symptoms of duodeno-gastric reflux are not specific. As a rule, the disease manifests itself with a predominance of dyspeptic symptoms - nausea, heartburn, air/sour belching, bitterness in the mouth and vomiting bile. Periodically appearing pain in the upper abdomen, intensifying after eating, is cramping in nature and can be provoked by stressful situations, physical activity, or appear after surgery for gastrectomy, cholecystectomy, and with developed duodenal obstruction. Since GHD in its “pure” form is rare and is diagnosed mainly against the background of other gastrointestinal diseases, especially gastroduodenal pathology, the clinical symptoms of reflux are influenced by the symptoms of the underlying disease, which to a certain extent masks the symptoms of GHD.

conclusions

1. The results of the study showed the following: GHD leads to inflammation, foveal hyperplasia, interstitial edema, fibroproliferation and ridge arborization.

2. H. pylori

leads to an increase in inflammation, manifested in the form of an increase in the activity and severity of inflammation, foveal hyperplasia, and the number of lymphoid follicles of mild and moderate severity.

3. GHD in children may have clinical manifestations in the form of pain and a painless course. With a pain syndrome, as with a painless course, changes in the morphological picture are noted equally, therefore it is incorrect to judge the severity of morphological changes by the severity of pain.

4. DGR leads to the development of certain morphological manifestations, which does not allow it to be regarded as a physiological process.

There is no conflict of interest.

Tests and diagnostics

The diagnosis is established on the basis of clinical symptoms and instrumental research methods, among which the most effective are:

- Daily pH-metry - allows you to assess the height of reflux and the profile of intragastric pH.

- Ultrasound diagnostics (echography with water load): with GHD, the retrograde movement of gas and liquid bubbles (corresponding to the reflux of duodenal contents into the stomach) from the pylorus to the body of the stomach is periodically recorded on echograms.

- Transillumination hemomotodynamic monitoring. The difference in motor wave amplitude in the antrum of the stomach and the duodenal bulb is used as a GDR parameter.

- Fibrogastroduodenoscopy (swelling of the coolant, focal hyperemia, pyloric dehiscence).

- X-ray of the stomach (regurgitation of barium from the duodenum into the stomach is noted).

- Fiberoptic spectrophotometry.

If bile reflux is suspected, differential diagnosis is made with acid gastroesophageal reflux and peptic ulcers of the stomach.

Diet

Diet for bile in the stomach

- Efficacy: therapeutic effect after 10 days

- Timing: constantly

- Cost of products: 1400-1500 rubles. in Week

Nutrition correction is a mandatory element of complex therapy. A diet is prescribed for bile in the stomach. Dietary nutrition is aimed at normalizing the motility of the gastroduodenal organs. The main nutritional requirements for the patient are: small frequent meals, adherence to a meal regimen, exclusion from the diet of spicy and salty foods, canned food, marinades, fatty, smoked and fried foods and dishes, wholemeal bread that reduce the rate of gastric emptying. The consumption of various vegetables and legumes rich in fiber (radishes, legumes, turnips, radishes, asparagus) and fruits with rough skin (gooseberries, grapes, dates, currants), as well as coarse cereals (pearl barley, barley, millet, corn) is limited. Limit the consumption of sugar, honey and jam, chocolate. The diet should be based on low-fat boiled, easily digestible foods: light soups, porridges, chicken meat without rough crust, boiled fish and vegetables/vegetable purees, fruit/oatmeal jelly.

Patients with GHD should avoid physical activity and heavy lifting after eating, which increases intra-abdominal pressure. It is equally important to prevent flatulence / constipation . However, since GHD occurs predominantly against the background of other gastrointestinal diseases, a diet for the underlying disease may be prescribed, for example, Diet No. 5 , Diet for gastric ulcer , Diet for gastritis , Diet for gastroduodenitis , etc.

GERD Treatment Methods

Treatment of GERD is carried out by a gastroenterologist. Treatment is aimed at relieving inflammation of the esophageal mucosa, reducing the frequency of reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus, reducing the damaging properties of refluxate (the substance that enters the esophagus from the stomach), and increasing the protective properties of the esophageal mucosa.

Of great importance is:

Drug treatment

Treatment with medications is prescribed by a doctor and must take into account the individual characteristics of the patient.

Lifestyle change

Normalization of lifestyle is of great importance. It is necessary to quit smoking, limit, or better yet eliminate, alcohol consumption. You should not eat fatty, spicy, sour foods, as well as coffee, tea, chocolate, legumes, cabbage, peas, and brown bread. It is better to take food more often (4-6 times a day), but in small portions. You should not eat before bed (the last meal should be 2-2.5 hours before bedtime). You should sleep with your upper body elevated to reduce the likelihood of reflux during sleep.

Make an appointment Do not self-medicate. Contact our specialists who will correctly diagnose and prescribe treatment.

Prevention

Prevention of GHD consists of:

- Timely treatment of gastrointestinal diseases (especially gastroduodenal pathology).

- Correction of body weight.

- Maintaining the correct diet to ensure physiologically normal gastrointestinal motility.

- Quitting smoking and alcohol abuse.

- Normalization of physical activity and psycho-emotional sphere. Elimination of factors that provoke reflux (lifting weights, exercises with strong abdominal tension, avoiding being in a horizontal position after eating, working in an inclined position).

- Exclusion/avoidance of long-term use of medications that worsen bile rheology and gallbladder motility (antibiotics, expectorants, sedatives, NSAIDs, estrogens, antispasmodics, β-blockers, hypnotics, calcium channel blockers).

Classification of the disease

There are several classifications of gastroduodenitis depending on the specific parameter, namely:

- According to the etiological factor - exogenous (external causes) and endogenous (internal causes) gastroduodenitis.

- According to the degree of prevalence - localized or diffuse.

- The course of the disease is latent, monotonous and recurrent.

- By origin - primary or secondary (occurs against the background of other diseases and conditions).

- According to the nature of gastric secretion - with increased, normal or decreased secretion.

- According to morphological indicators - superficial, hypertrophic, erosive, hemorrhagic, subatrophic and mixed.

List of sources

- Zvyagintseva T.D., Chernobay A.I. Functional disorders of the motor-evacuation function of the digestive tract and their pathogenetic correction // News of medicine and pharmacy. – 2009.– No. 294. pp. 7–11.

- Zvyagintseva T.D., Chernobay A.I. Duodenogastric reflux in the practice of a gastroenterologist: obvious dangers and hidden threats // Medical newspaper “Health of Ukraine”. 2012.—No. 1. P.11.

- Trukhan D.I., Filimonov S.N. Differential diagnosis of the main gastroenterological syndromes and symptoms. M.: Practical Medicine, 2021. 168 p.

- Trukhan D.I. Rational pharmacotherapy in gastroenterology // Directory of a polyclinic doctor. 2012. No. 10. pp. 18–24.

- Bagnenko G.F., Nazarov E.V., Kabanov M.Yu. Methods of pharmacological correction of motor-evacuation disorders of the stomach and duodenum. // Rus. honey. magazine. Diseases of the digestive system. –2004. – T. 1. – P. 19-23.