Publications in the media

Status asthmaticus (life-threatening exacerbation of bronchial asthma) is an asthmatic attack of unusual severity for a given patient, resistant to bronchodilator therapy that is usual for a given patient. Status asthmaticus also refers to severe exacerbation of bronchial asthma, requiring medical care in a hospital setting. One of the reasons for the development of status asthmaticus may be blockade of b2-adrenergic receptors due to an overdose of b2-adrenergic agonists.

Reasons : • Inaccessibility of constant medical care • Lack of objective monitoring of the condition, including peak flowmetry • The patient’s inability to self-control • Inadequate previous treatment (usually the absence of basic therapy) • Severe attack of bronchial asthma, aggravated by concomitant diseases that complicate treatment in an outpatient setting (for example, psychiatric).

Clinical manifestations

• Increasing resistance to bronchodilators, combined with manifestations of their side effects due to overdose.

• Progressive difficulty in sputum discharge.

• Manifestations characteristic of a normal attack of bronchial asthma, but expressed to an extreme degree. The duration of exhalation is sharply prolonged, dry whistling and buzzing rales are heard, and with progression, breathing becomes weakened, up to “silent lungs” (absence of breathing sounds on auscultation), which reflects the extreme degree of bronchial obstruction.

• Possible development of hypoxemic hypercapnic coma •• Cerebral disorders •• Arterial hypotension •• Collapse.

TREATMENT

Treatment tactics

• Hospitalization.

• First line therapy. Oxygen therapy (1–4 L/min via nasal catheter), hypercapnia is not an obstacle. Inhalation of b2-adrenergic agonists (in the absence of a history of overdose) is better through a nebulizer (salbutamol, fenoterol) or through a can using large-volume spacers (750 ml) with a unidirectional inhalation valve. To prevent cardiovascular complications from this group of drugs, adequate oxygen therapy is necessary. GC is prescribed as early as possible; intravenous and oral routes of administration are equally effective (40–125 mg methylprednisolone IV every 6 hours, followed by 40–80 mg prednisolone per day orally).

• If the condition has not improved, but there is no need for mechanical ventilation, the following are indicated: •• inhalation of an oxygen-helium mixture (causes a decrease in resistance to gas flows in the respiratory tract, turbulent flows in the small bronchi become laminar) •• administration of magnesium sulfate intravenously •• assisted non-invasive ventilation.

• Transfer of a patient with status asthmaticus to mechanical ventilation is carried out according to vital indications in any setting (outside a medical institution, in the emergency department, in the general ward or intensive care unit). The procedure is performed by an anesthesiologist or resuscitator. The goals of mechanical ventilation for bronchial asthma are to support oxygenation, normalize blood pH, and prevent iatrogenic complications. In some cases, during mechanical ventilation of the lungs, intravenous infusion of sodium bicarbonate solution is necessary.

• Second line therapy. Anticholinergic drugs - ipratropium bromide and its combination with a b2-adrenergic agonist (ipratropium bromide + fenoterol) - through a nebulizer followed by transfer to a can with a spacer. Theophylline preparations are administered intravenously under monitoring of serum levels during the first 6 hours from the start of treatment. If there is no effect from inhaled bronchodilators, 0.5 mg (or 4-8 mcg/kg) of salbutamol or terbutaline is administered intravenously over 1 hour.

• Subcutaneous administration of b2-adrenergic agonists is indicated if the development of status is an integral part of a systemic allergic (anaphylactic) reaction, the patient’s consciousness is impaired or there is a threat of respiratory arrest, and there is no effect of inhalation therapy. Epinephrine is administered at a dose of 0.3 mg at intervals of 20 minutes during the first hour and subsequently after 4–6 hours. • The patient remains in the hospital until nocturnal attacks disappear and the patient’s subjective need for short-acting bronchodilators decreases to 3–4 inhalations per day. day.

ICD-10 • J46 Asthmatic status [status asthmaticus]

Bronchial asthma

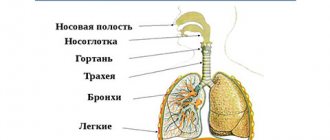

Bronchial asthma is a chronic relapsing disease with predominant damage to the respiratory tract, which is based on chronic allergic inflammation of the bronchi, accompanied by their hyperreactivity and periodic attacks of difficulty breathing or suffocation as a result of widespread bronchial obstruction, which is caused by bronchospasm, hypersecretion of mucus, and swelling of the bronchial wall.

There are two forms of bronchial asthma - immunological and non-immunological - and a number of clinical and pathogenetic variants: atopic, infectious-allergic, autoimmune, dishormonal, neuropsychic, adrenergic imbalance, primary altered bronchial reactivity (including “aspirin” asthma and physical effort asthma ), cholinergic.

Etiology and risk factors for the occurrence of bronchial asthma in children: atopy, bronchial hyperreactivity, heredity. Causes (sensitizing): household allergens (house dust, house dust mites), epidermal allergens of animals, birds, and insects, fungal allergens, pollen allergens, food allergens, drugs, viruses and vaccines, chemicals.

Pathogenesis. The general pathogenetic mechanism is a change in the sensitivity and reactivity of the bronchi, determined by the reaction of bronchial patency in response to the influence of physical and pharmacological factors.

It is believed that in 1/3 of patients (mainly those suffering from the atonic variant of the disease) asthma is of hereditary origin. The most studied allergic mechanisms of asthma are based on IgE- or IgG-mediated reactions. Leukotrienes play a central role in the pathogenesis of aspirin-induced asthma. In physical exertion asthma, the process of heat transfer from the surface of the respiratory tract is disrupted.

Clinic. The disease often begins with a paroxysmal cough, accompanied by shortness of breath with the discharge of a small amount of glassy sputum (asthmatic bronchitis). The full picture of bronchial asthma is characterized by the appearance of mild, moderate or severe attacks of suffocation. An attack may begin with a precursor (profuse discharge of watery secretion from the nose, sneezing, paroxysmal cough, etc.).

An attack of bronchial asthma is characterized by a short inhalation and an extended exhalation, accompanied by wheezing audible from a distance. The chest is in the position of maximum inspiration, the patient takes a forced position, sitting on the bed, dangling his legs down, tilting his torso slightly forward. The muscles of the shoulder girdle, back, and abdominal wall take part in breathing. When percussing over the lungs, a box sound is determined; upon auscultation, many dry rales are heard. The attack often ends with the release of viscous sputum.

Severe prolonged attacks can develop into an asthmatic state - one of the most dangerous options for the course of the disease.

Asthmatic status

Status asthmaticus is a persistent broncho-obstructive syndrome, in which previously helpful bronchodilators become ineffective, sputum production stops completely and elements of multiple organ failure appear - circulatory decompensation, impaired diuresis and others.

Among the main risk factors for the development of status asthmaticus are massive exposure to allergens, respiratory infections, changes in meteorological conditions, psycho-emotional overload, and inadequate treatment. More than half of cases of status asthmaticus are diagnosed in patients with steroid-dependent bronchial asthma.

Unlike a prolonged attack of bronchial asthma, in status asthmaticus the basis of pathogenesis is not bronchiolospasm, but swelling, inflammation, dyskinesia of the small airways and blockage of them with viscous, non-evacuable sputum. From the moment sputum ceases to be drained using the natural mechanisms of clearing the airways, it can be assumed that a prolonged attack of bronchial asthma has turned into asthmatic status.

Depending on the severity of obstructive ventilation disorders in the clinical course of status asthmaticus, 3 stages are distinguished.

Stage 1

(relative compensation) is characterized by the development of a long-term uncontrollable attack of suffocation. Patients are excited, speech is difficult. Shortness of breath, cyanosis, sweating are moderately expressed. On auscultation, breathing is weakened, carried out in all parts, dry scattered rales. The peak expiratory flow rate, determined using a peak flow meter, is reduced to 50-80% of the proper value. At this stage, hyperventilation, hypocapnia, and moderate hypoxemia are most often observed.

Stage 2

(decompensation or “silent lung”) is characterized by a further increase in bronchial obstruction (peak expiratory flow is less than 50% of the proper value), hyperventilation is replaced by hypoventilation, hypoxemia worsens, hypercapnia and respiratory acidosis appear. On auscultation, areas of the “silent lung” are heard while remote wheezing persists. The patient cannot say a single phrase without taking a breath. Tachycardia up to 130-140 per minute, arrhythmias are often observed.

For stage 3

(hypoxic and hypercapnic coma) is characterized by an extremely serious condition with severe cerebral disorders. Thread-like pulse, hypotension, collaptoid state. Peak expiratory flow is less than 30% of normal.

Death of patients with status asthmaticus occurs as a result of progressive bronchial obstruction, with the failure of therapeutic measures, the inability to provide effective ventilation, as well as due to severe hemodynamic disturbances or as a result of unrecognized tension pneumothorax

The drugs used in the intensive treatment of status asthmaticus are similar to those in the basic treatment of bronchial asthma, but other dosage forms are also used. In case of an asthmatic condition, short-acting drugs are prescribed, that is, long-acting sympathomimetics are canceled. This is dictated by the need to titrate doses individually over a short period of time. Long-acting corticosteroids should be especially avoided.

First-line drugs include β2 agonists. These drugs have a bronchodilator and mucokinetic effect, reduce the viscosity of sputum, reduce swelling of the mucous membrane and increase the contractility of the diaphragm. Treatment should begin with salbutamol in a dose of 5 mg of solution through a nebulizer every 20 minutes for 1 hour, then after 1-4 hours. Nebulizer therapy, unlike “pocket” inhalers, makes it possible to inhale high doses of drugs and avoid the irritating effects of propylenes . It is advisable to combine β2-adrenergic agonists with anticholinergics. A good effect is achieved by combining salbutamol and ipratropium bromide (Atrovent), which potentiates the bronchodilation effect. When inhalation therapy is ineffective, aminophylline is used. The initial dose of aminophylline is 240 mg intravenously over 20 minutes (if the patient has not received it previously). The maintenance dose of aminophylline is administered at the rate of 0.5-0.6 mg/kg/h). The daily dose is 0.75-1.5 g. The use of aminophylline requires constant monitoring of cardiac activity, due to frequent tachycardia and arrhythmias.

In the absence of response to bronchodilator therapy and previous treatment with tableted corticosteroids, glucocorticoid therapy is indicated. The usual dosage of hydrocortisone is up to 1000 mg per day, metipred is up to 500 mg per day. Corticoids reduce bronchial hyperreactivity, have an anti-inflammatory effect, increase the activity of β2-agonists and promote the reactivation of β2-adrenergic receptors.

Blood thickening, often observed in status asthmaticus, associated with impaired fluid intake with increased perspiration losses, requires control of hematocrit and blood thinning with infusion of crystalloid solutions. This also helps to improve the mucociliary removal of sputum, since it is impossible to establish sufficient drainage under conditions of hypohydration.

It should be remembered that any sedatives are categorically undesirable during exacerbation of bronchial asthma.

Intensive therapy for status asthmaticus is carried out against the background of oxygen therapy with an oxygen content of at least 30%.

For progressive gas exchange disorders that are not amenable to intensive therapy, mechanical ventilation. First of all, it provides the necessary amount of ventilation when respiratory failure and hypoventilation become life-threatening.

Indications for mechanical ventilation in status asthmaticus are determined primarily by the clinical picture. The basis for transfer to mechanical ventilation is the steady progression of respiratory failure and hypoventilation, accompanied by depression of consciousness, an increase in PaCO2 and hypoxemia, severe heart failure and severe cardiac arrhythmias.

An important effect of mechanical ventilation in status asthmaticus is an increase in collateral ventilation, due to which air appears behind the mucus plugs, facilitating its removal, as well as the possibility of washing (lavage) of the respiratory tract. During mechanical ventilation, one should avoid increasing the “overinflation” of the lungs, avoiding the development of high pressure in the respiratory tract (over 35 cm of water column), since ruptures of bullous lung tissue and the occurrence of tension pneumothorax are possible.

Being the most severe manifestation of bronchial asthma, the asthmatic condition has a high mortality rate among young, able-bodied patients. The prevalence of this terrible condition, according to the literature, ranges from 17 to 79% among all forms of bronchial asthma, and the mortality rate ranges from 16.5 to 17% or more.

Early diagnosis and rational intensive therapy provide reliable prevention of status asthmaticus, in the late stages of which the effectiveness of treatment becomes questionable.

Head of the intensive care and resuscitation department No. 2 Mazur Vadim Vilenovich

Doctor of the intensive care and resuscitation department No. 2 Olga Aleksandrovna Klimova

Asthmatic status

(AS) is an attack of severe suffocation caused by a complication of the chronic course of bronchial asthma. AS differs from ordinary attacks of bronchial asthma in its more severe and prolonged course, resistance to standard therapy, and distinct signs of acute respiratory failure (ARF). The duration of AS can be from several hours to 4-6 days or more. AS is potentially life-threatening. One of the causes of death is the late start of treatment and untimely hospitalization of patients in intensive care units.

Asthmatic status

is a prolonged attack of bronchial asthma, resistant to therapy and characterized by severe or progressive ARF caused by obstruction of the airways, with the patient developing resistance to adrenergic stimulants.

It is fundamentally important to distinguish between two forms of the asthmatic condition. First form of asthmatic condition

- develops quickly and proceeds like anaphylactic shock.

Despite the lightning speed of development of the first form

of the asthmatic condition, its clinical picture has

two stages

:

• the first stage is shock, which is preceded by a symptom complex of acute diffuse bronchospasm and acute respiratory failure;

• the second stage is coma, caused by very quickly developing acute heart failure and increasing hypoxia.

Second form

asthmatic state (the period of transformation of an exacerbation of bronchial asthma into an asthmatic state is extended over time). The most characteristic thing in the development of this form is gradualism, but at the same time progression. One of the leading pathogenetic signs is progressive functional blockade of beta-adrenergic receptors.

The main reasons for the development of status asthmaticus

are: exacerbation of chronic obstructive diseases, acute pneumonia, sinusitis, polyp removal surgery, exacerbation of cholecystopancreatitis, breaks in corticosteroid therapy.

In status asthmaticus, patients die from acute right ventricular failure, gradually developing thrombosis of small branches of the pulmonary artery, relative adrenal insufficiency in hormone-dependent patients, acute respiratory failure (hypoxemic coma).

As our clinical experience shows, it is advisable to distinguish a period of asthmatic status, which can be called “unstable asthma” (periods of threat of asthmatic status).

Clinical characteristics of “unstable asthma”

: • increased frequency of attacks; • change in the nature of attacks; • increasing resistance to therapy. Most of these patients have a history of abuse of sympathomimetics, hypnotics and sedatives for several days, with which the patient tries to eliminate suffocation.

Recommendations for assessing the condition and management of patients with bronchial asthma are based on data from a clinical and instrumental examination of the patient and the effect of inhalation of sympathomimetics.

1.Clinical assessment

- Speech is an important clinical sign of obstruction (hyper-airiness of the lung tissue - the alveoli can no longer fill with air). It can be: 1) not impaired, 2) the patient cannot speak whole sentences, 3) pronounces individual words. - “Fatigue” of the respiratory muscles. Accessory muscles are involved in the act of breathing; Paradoxical thoracoabdominal movements may be observed: - respiratory rate; - heart rate, the appearance of arrhythmic episodes or bradycardia; - changes in blood pressure; - presence of cyanosis; — auscultation — the presence of zones of “silent” lung; - The risk of pneumothorax is high in children, adolescents and women.

2. Instrumental methods

• Determination of peak expiratory flow • Oxygen saturation.

3. Evaluation of the therapeutic effect of inhalation of short-acting sympathomimetics

.

Depending on the changes and dynamics of these indicators, the following forms can be distinguished and the doctor’s treatment tactics can be determined:

Uncontrollable

(treatment evading) asthma: • speech is not impaired;

• participation of the respiratory muscles is not expressed; • attacks appear at night; • BH less than 25; • Heart rate is less than 100; • PSV-60-80%. • Inhalation of a short-acting agonist gives good results: - absence of wheezing/shortness of breath; - response to agonist lasts at least 4 hours. The doctor's tactics

- the patient can be left at home with recommendations: continue taking the agonist with a frequency of inhalations - every 3-4 hours for 24-48 hours. A patient on an inhaled corticosteroid needs to double the dose of the drug for 7-10 days. After this, contact with the attending physician to develop further tactics for managing the patient.

Exacerbation of asthma

(a further increase in symptoms is noted): • speech in incomplete sentences;

• pronounced participation of the respiratory muscles; • BH is more than 25; • Heart rate is less than PO; • PSV-less than 50%; • incomplete response to inhaled short-acting agonist implies persistent wheezing with shortness of breath. Physician's tactics

- it is recommended to continue treatment with the addition of an oral corticosteroid against the background of discontinued agonist treatment. Urgent contact with the attending physician is necessary, hospitalization is indicated.

Life-threatening condition

: • speech in separate words; • paradoxical thoracoabdominal movement (fatigue of the respiratory muscles) may be observed, i.e. severe ventilation disorders that may require mechanical ventilation; • RR greater than 30, cyanosis, upon auscultation of the “silent” lung zone; • Heart rate is more than 130, arrhythmic episodes, periods of bradycardia, and often there is an increase in blood pressure. Sweating, decreased diuresis. There is a high risk of pneumothorax; • PSV - less than 30%, oxygen saturation - 40-60%; • poor result on inhalation with sympathomimetics (beta-agonists do not reach the small bronchi) - wheezing with shortness of breath.

Stages of status asthmaticus:

a) I - initial stage: - frequent attacks of severe suffocation, during the treatment of which the quality of breathing is not completely restored or failure to relieve an asthma attack with sympathomimetics - resistance to commonly used bronchodilators with the formation of cardiotoxic reactions (arrhythmias) - forced position of patients, “gray” cyanosis skin and visible mucous membranes - lethargy and mental depression of the patient - respiratory disorders with tachypnea up to 32-40/min; breathing in the lower parts of the lungs is audible - sinus tachycardia up to 130-140 beats/min, hypertension due to impaired biotransformation of catecholamines and an imbalance in the functional state of α- and β-adrenergic receptors. b) II - advanced stage: - constant and painful suffocation - pronounced toxic effect of the used bronchodilators (palpitations and chest pain, nausea and vomiting, tremor of the fingers) - unproductive cough - forced position of the patient, moist gray-cyanotic skin or diffuse cyanosis - mental depression of the patient, which alternates with periods of excitation - superficial tachypnea up to 40-50/min, according to auscultation - the appearance of “silent lung” zones (areas of the lung with a complete absence of vesicular breathing, a decrease in the number of dry rales, the appearance of areas where wheezing does not occur) audible) - high tachycardia, in 1/3 of patients arterial hypertension is replaced by hypotension c) III - hypoxemic coma: - loss of consciousness, preceded by delirium or an episode of convulsions - cold, gray-cyanotic skin, constantly increasing diffuse cyanosis - in 1/3 patients, previous tachypnea is replaced by bradypnea, deep breathing, exhalation is sharply prolonged - “silent lungs” on auscultation - pulse 150–170 beats/min, thread-like, deep arterial hypotension in 2/3 of patients - a sharp drop in oxygen tension in the blood and an increase in carbon dioxide tension A patient with any stage of AS is hospitalized on a stretcher in a sitting position in the intensive care unit.

Emergency treatment:

1. Refusal to use any adrenergic stimulants 2. IV access, infusion of 200 mg of hydrocortisone sodium succinate or 90-120 mg of prednisolone IV in a stream followed by continuous administration of hydrocortisone IV drip (if there is no effect, the dose of GCS is increased by 1.5 -3 times or more) 3. Slow microjet intravenous administration of 120–240 mg of aminophylline followed by intravenous drip infusion of the drug at the rate of 1 mg/kg/hour until the patient’s condition improves 4. Infusion therapy: 400–600 ml of isotonic solution - sodium chloride for 3 hours intravenously, then rheopolyglucin (reomacrodex, neorondex) intravenously with heparinization of infusion media (2500 units of heparin for every 400-500 ml of solution) + sodium iodide 10% solution p 10-30 ml/day IV - for rehydration, thinning and better removal of sputum 5. Oxygen therapy through a leaky face mask or nasopharyngeal catheters at a rate of 2-6 l/min 6. With significant anxiety of the patient: 2.5–5 mg IV droperidol (sedative effect, reduction of psychotic phenomena, reduction of toxic effects of sympathomimetics, reduction of blood pressure by 40-60 mm Hg. for hypertension) 7. If possible, therapeutic bronchoscopy with segmental lavage of the bronchial tree is recommended 8. If it is necessary to intubate the patient, use calypsol (ketamine) up to 4 mg/kg IV (in combination with controlled mechanical ventilation allows stopping AS within 30 minutes) NB! Other sedatives, opiates and opioids, antihistamines against the background of AS are contraindicated due to the danger of depression of the respiratory center!!!