Dengue is a mosquito-borne viral disease that has been spreading rapidly in all WHO regions in recent years. The dengue virus is transmitted by female mosquitoes, mainly Aedes aegypti and, to a lesser extent, Ae. albopictus. These mosquitoes also transmit chikungunya, yellow fever and Zika viruses. Dengue is widespread in the tropics, with the risk of infection varying from place to place depending on factors such as rainfall patterns, temperature, relative humidity and the presence of undeveloped urban areas.

Dengue causes a wide range of clinical manifestations. In infected people, they can range from subclinical symptoms (people may not be aware of the infection) to severe flu-like symptoms. Some patients, although less frequently, develop severe dengue, which can present with a range of complications due to severe bleeding, organ damage and/or plasma leakage from the bloodstream. Without proper treatment, severe dengue is more likely to be fatal. Severe dengue was first identified in the 1950s. during dengue epidemics in the Philippines and Thailand. Severe dengue is now common in most Asian and Latin American countries and is one of the leading causes of hospitalization and death in children in these regions.

The causative agent of dengue is a virus of the Flaviviridae family; There are four different but closely related serotypes of the virus that cause dengue (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4). It is assumed that after an infection, a person develops lifelong immunity to a specific serotype. However, cross-immunity to other serotypes after recovery is only partial and temporary. Subsequent episodes of infection (secondary infection) with other serotypes increase the risk of developing severe dengue.

Dengue has distinct epidemiological features associated with four serotypes of the virus. Different serotypes can circulate simultaneously within the same region, and in fact many countries are hyperendemic for all four serotypes. The impact of dengue on children's health and on global and national economies is alarming. DENV is often carried from one location to another by infected individuals during travel; the presence of potential carriers in the areas of arrival of such persons creates the preconditions for local transmission of infection.

Global Dengue Burden

Over the past decades, the incidence of dengue in the world has increased sharply. In the vast majority of infected people, the infection is asymptomatic or mild and without seeking medical help, and therefore actual cases of the disease are not fully registered. In addition, dengue is often mistaken for other febrile diseases [1].

One model estimates that 390 million dengue virus infections occur annually (95% confidence interval 284–528 million), of which 96 million (67–136 million) are clinical (all disease severity) [2]. Another study on dengue prevalence estimates that 3.9 million people are at risk of contracting dengue viruses. Although the risk of infection exists in 129 countries [3], 70% of the actual disease burden occurs in Asia [2].

Over the past two decades, the number of dengue cases notified to WHO has increased more than eightfold, from 505,430 cases in 2000 to more than 2.4 million in 2010 and 5.2 million in 2021. registered deaths between 2000 and 2015 increased from 960 to 4,032.

This alarming increase in incidence is partly due to changes in national practices for registering cases and reporting dengue to ministries of health and WHO. But it also shows that governments recognize the burden of dengue and therefore the importance of reporting on that burden. Therefore, although the true global burden of disease has not been established, the observed increase nevertheless brings us closer to a more accurate estimate of its magnitude.

Pakbara - Hat Yai (continent)

We were met by an ambulance team in a reanimobile. The patient was placed on a gurney, causing increased attention from everyone waiting for the transfer on the pier. They turned on the flashing lights and rushed off, not stopping at traffic lights and overtaking the flow of oncoming traffic.

The hospital in Hat Yai is of an international level: an emergency department with equipment, comfortable and modern boxes. But we didn’t meet a single European there: the patients and medical staff were Thai.

About 8 people examined Vinsky, standing around the gurney. My feet looked and I felt extremely uncomfortable because my feet were dirty - on Koh Lipe I walked barefoot on the ground and sand. They brought it to a box for one - it was great: spacious, bright, there was a TV. But there are two of us. - Do you have something better and bigger? — There is a luxury suite, but it costs more than the one we agreed on with the insurance company. - No question - we will pay the difference. And we were transferred to a two-room apartment with two bathrooms, a kitchen and panoramic views of the city of Hat Yai. An important point: the next day the insurance company confirmed that it would cover these costs itself and in full .

Dengue spread and outbreaks

Before 1970, severe dengue epidemics occurred in only nine countries. The disease is currently endemic in more than 100 countries in the African, American, Eastern Mediterranean, Southeast Asian and Western Pacific regions. The regions most affected are the Americas, Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific, with Asia accounting for about 70% of the global burden of disease.

The spread of the disease to new areas, including in Europe, is accompanied not only by an increase in the number of cases, but also by rapid outbreaks. The threat of dengue outbreaks in Europe has emerged in recent years; In 2010, local transmission was reported for the first time in France and Croatia, and imported cases were detected in three other European countries. In 2012, a dengue outbreak on the island of Madeira, Portugal, infected more than 2000 people, with imported cases detected in mainland Portugal and ten other European countries. Currently, autochthonous cases of the disease occur almost annually in many European countries. Dengue is the second most commonly diagnosed cause of fever in people returning from travel to low- and middle-income countries, after malaria.

In 2021, dengue was imported into several new countries and countries such as Bangladesh, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Yemen, Mauritania, Maldives, Mayotte (France), Nepal, Cook Islands, Singapore, Sudan, Thailand, Timor -Leste, Sri Lanka and Ecuador have seen an increase in the number of cases. In 2021, dengue continues to spread in Brazil, the Cook Islands, Colombia, Fiji, Kenya, Paraguay, Peru and Reunion Island.

The COVID-19 pandemic is placing extraordinary strain on health and governance systems around the world. WHO emphasizes the importance of continuing efforts to prevent, detect and treat vector-borne diseases such as dengue and other arbovirus infections during this difficult period, given the increase in the number of cases of both groups of diseases that most threaten urban populations. The combined impact of the COVID-19 and dengue epidemics could potentially lead to catastrophic consequences for at-risk populations.

In 2021, a record number of dengue cases were reported worldwide. All WHO regions were affected; dengue transmission was first identified in Afghanistan.

In the Region of the Americas alone, 3.1 million cases were reported, with more than 25 000 cases classified as severe. Despite the alarming incidence statistics, the number of dengue-related deaths was lower than the previous year.

In Asia, the highest numbers of infections were reported in Bangladesh (101,000), Vietnam (320,000), Malaysia (131,000) and the Philippines (420,000).

2021 also saw major dengue outbreaks, with more than 2.38 million cases reported in the Region of the Americas. There were about 1.5 million cases in Brazil alone that year, about three times more than in 2014; the region also reported 1,032 dengue deaths. In the same year, there were more than 375 000 suspected dengue cases in the Western Pacific Region, of which 176 411 cases were reported in the Philippines and 100 028 cases in Malaysia, similar to the disease burden in these two countries in the previous year . An outbreak was declared in the Solomon Islands, where more than 7,000 people were suspected of infection. In the African Region, a localized dengue outbreak was reported in Burkina Faso, where there were 1,061 suspected cases.

In 2021, the Americas recorded a significant decrease in the number of infections: from 2,177,171 cases in 2021 to 584,263 cases in 2021. Accordingly, the decrease was 73%. Only Panama, Peru and Aruba saw an increase in cases in 2021.

Similarly, a 53% reduction in severe dengue cases was reported in 2021. The decline in dengue cases has occurred since the Zika virus outbreak (post-2021), but the specific factors contributing to the decline are still unknown.

Conclusions about medicine on Koh Lipe

1. When applying through an insurance company or at your own expense, avoid the Siam International clinic on Walking street. The other two (see above) have a decent level of service. In one we treated ourselves, about the second I heard positive reviews similar to ours. 2. If you pay in cash without insurance, bargain for every penny . 3. No insurance company will provide you with a translator. They simply aren't on the island. Without English (or Thai) in the hospital it will be difficult. 4. Better not get sick!

Transmission of infection

Transmission of infection from mosquito to person

The virus is transmitted to humans when they are bitten by an infected female mosquito, mainly Aedes aegypti. Other species of the genus Aedes can also transmit the infection, but to a lesser extent than Aedes aegypti.

The virus is acquired by a mosquito when a mosquito bites a DENV-infected person, where it replicates in the mosquito's midgut and then spreads to secondary tissues, including the salivary glands. The period of time from the moment the virus enters the mosquito's body until it is actually transmitted to a new host is called the external incubation period (EIP). At ambient temperatures between 25–28°C, the IP is about 8–12 days [4–6]. The duration of the external incubation period is influenced not only by the ambient temperature; the time it takes a mosquito to transmit the virus may also vary due to a number of other factors, such as the range of daily temperature fluctuations [7, 8], virus genotype [9], and initial virus concentration [10]. Once infected, the mosquito is able to transmit the virus for the rest of its life.

Transmission of infection from humans to mosquitoes

Mosquitoes can become infected from people infected with DENV. These may include individuals with symptomatic dengue infection, individuals who do not yet have symptomatic infection (pre-symptomatic patients), and individuals who do not have any signs of disease (asymptomatic patients) [11].

Transmission of the virus from a person to a mosquito is possible in the period from two days before the onset of symptoms of the disease in humans [5, 11] until two days after the end of the fever [12].

The risk of mosquito infection is positively correlated with high levels of viremia and high fever in the patient; conversely, high levels of DENV-specific antibodies are associated with a reduced risk of mosquito infection (Nguyen et al 2013 PNAS). Most people remain infectious for about four to five days, but viremia can last up to 12 days [13].

Other mechanisms of virus transmission

The main vectors of DENV among humans are mosquitoes. However, there is evidence indicating the possible transmission of infection from the mother (from a pregnant woman to her child). Rates of vertical transmission appear to be low, but the risk appears to be related to the stage of pregnancy when dengue infection occurs [14–17]. Children of mothers infected with DENV during pregnancy may suffer from prematurity, low birth weight, and fetal distress [18].

Vectors of infection in the environment

The main carriers of DENV are Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. They live in urban environments and breed mainly in artificial containers. Ae. aegypti feed during the daytime; Their peak biting times are in the early morning and evening before sunset [19]. During each feeding period, the female Ae. Aegypti bites a large number of people [20]. Eggs laid by the female can remain viable for several months, and upon contact with water, they hatch into larvae.

Aedes albopictus, the second most important vector of dengue in Asia, has spread to more than 32 states in the United States and more than 25 countries in the European Region, largely as a result of international trade in waste tires (which provide breeding habitat) and other products (such as ornamental bamboo). Ae. Albopictus easily adapts to new conditions. Its geographic distribution is largely due to its ability to tolerate lower temperatures both as an egg and as an adult [21, 22]. Aedes albopictus is the main vector of DENV in a limited number of outbreaks – where Aedes aegypti is either not present or present in low numbers [23, 24].

Characteristics of the disease (signs and symptoms)

Dengue is a severe flu-like illness that affects infants, young children and adults, but rarely causes death. Symptoms typically last 2–7 days after an incubation period of four to ten days following the bite of an infected mosquito [25]. The World Health Organization distinguishes two main categories of disease: dengue (with/without signs of complications) and severe dengue. The classification into the subcategories of dengue with signs of complications and dengue without signs of complications is intended to assist health care providers in triaging hospitalized patients, ensuring close monitoring, and minimizing the risk of developing more severe dengue (see below).

Dengue

Dengue should be suspected when a high temperature (40°C/104°F) in the febrile stage is accompanied by two of the following symptoms:

- Strong headache;

- Pain in the eyes;

- muscle and joint pain;

- nausea;

- vomit;

- swollen glands;

- rash.

Severe dengue

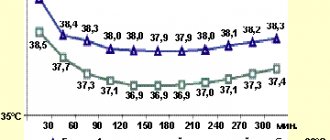

3–7 days after the onset of the disease, the patient usually enters the so-called critical stage. It is at this time, when the temperature drops (below 38°C/100°F), that the patient may show signs of complications associated with severe dengue. Severe dengue is a complication that can be fatal due to plasma leakage from the bloodstream, fluid accumulation, respiratory failure, severe bleeding or organ damage.

Signs of complications that your doctor should watch for include the following:

- severe pain in the abdominal area;

- constant vomiting;

- rapid breathing;

- bleeding gums;

- weakness;

- excited state;

- vomiting blood.

Patients who develop the above symptoms at a critical stage should be closely monitored for the next 24 to 48 hours to ensure appropriate medical care to avoid complications and the risk of death.

Diagnostics

Several methods can be used to diagnose DENV infection. These include virological studies (allowing the direct detection of elements of the virus) and serological studies (allowing the detection of immune components produced by the human body in response to the virus). The use of various diagnostic methods may be more or less appropriate depending on the time of the patient's presentation. Samples of patient biomaterial obtained during the first week of the disease should be tested by both serological and virological methods (RT-PCR).

Virological methods

The virus can be isolated from the blood within the first few days of infection. There are different methods based on reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). In general, RT-PCR methods are sensitive, but they require specialized equipment and technical training of testing personnel and are not available in all health care settings. RT-PCR material obtained from clinical samples can also be used for virus genotyping, allowing comparisons with virus samples from different geographic sources.

The virus can also be detected by testing for a viral protein called NS1. For this purpose, there are industrially produced diagnostic rapid tests that provide results in only about 20 minutes without any special laboratory techniques or equipment.

Serological methods

Serological methods, in particular enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), can confirm the presence of recent or past infection by detecting IgM and IgG antibodies to dengue. IgM antibodies are detectable approximately one week after infection and reach maximum levels 2–4 weeks after the onset of illness. They can be detected for about three months. The presence of IgM indicates recent DENV infection. IgG antibodies take longer to reach maximum levels compared to IgM, but IgG remain in the body for years. The presence of IgG indicates a past infection.

Review of the SAMC clinic on Koh Lipe

When we arrived at the SAMC clinic, the doctor and his assistant were already waiting for us and ran out to greet us. Also striking in contrast was the presence of everything that was missing in terms of sanitation at the Siam clinic.

What I liked most was that they immediately began the examination, questioning about symptoms, and not financial and insurance settlements. In this clinic, we were not asked for any documents, nor were we asked to sign anything. Later (before evacuation to the mainland they only asked for a copy of the passport).

Test results for all kinds of tropical fevers were ready within 10 minutes. Dengue fever confirmed.

It was hard to believe: for years we have been traveling around Southeast Asia, South America, the Caribbean, Australia, Oceania and Africa. Mosquitoes and tsetse flies bit - not without it. Apparently I was just lucky.

The doctor is young, attentive and efficient. He gave us exactly the time we needed. And on the first day we needed an IV for 4 hours. In a separate room of the clinic.

Since Dengue is not treated, but observed , the doctor asked me to come again in the evening for a blood test. According to his forecast, in the next day or two the temperature will drop and health will improve.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for dengue fever.

For muscle and other pain, as well as to reduce temperature, you can take antipyretic and painkillers.

- The best medications to relieve these symptoms are acetaminophen or paracetamol.

- NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) such as ibuprofen and aspirin should be avoided. These anti-inflammatory drugs act by thinning the blood, and in conditions where there is a risk of hemorrhage, anticoagulants may worsen the poor prognosis.

In cases of severe dengue, care from doctors and nurses trained in the presentation and progression of the disease can save lives and reduce mortality rates from more than 20% to less than 1%. When treating severe dengue, maintaining adequate fluid levels in the patient's body is critical. Patients with dengue should seek medical attention if signs of complications occur.

Possible consequences, complications

Viral particles through the bloodstream easily enter the liver, muscles, bone marrow and nervous system. Due to the destruction of affected cells, there is a high probability of developing many complications, for example:

- meningitis, encephalitis, in severe cases – cerebral edema;

- acute psychoses;

- nerve inflammation;

- otitis;

- with damage to glandular tissue - mumps, orchitis;

- thrombophlebitis;

- infectious-toxic shock.

During the period of bearing a child, the disease is most dangerous, since there is a high probability of miscarriage, premature birth or intrauterine fetal death.

Dengue vaccination

The first dengue vaccine, Dengvaxia® (CYD-TDV), developed by Sanofi Pasteur, was licensed in December 2015 and has already been registered by regulatory authorities in approximately 20 countries. In November 2021, results of an additional analysis were released to retrospectively determine the serostatus of individuals at the time of their vaccination. The analysis showed that a subgroup of study participants believed to be seronegative at the time of first vaccination were at increased risk of more severe dengue and hospitalization as a result of the disease compared with unvaccinated participants. The vaccine is therefore intended for use in people aged nine to 45 years living in endemic areas and with a history of at least one documented episode of dengue virus infection.

WHO position on CYD-TDV vaccine

As noted in the WHO position paper on Dengvaxia (September 2021), the live attenuated dengue vaccine CYD-TDV has demonstrated efficacy and safety in individuals who have previously had dengue infection (seropositive individuals) in clinical trials. However, it is associated with an increased risk of developing severe dengue in individuals who were first naturally infected with dengue after vaccination (who were seronegative at the time of vaccination). The recommended strategy for countries considering vaccination as part of a dengue control program is to conduct pre-vaccination screening. Under this strategy, only individuals with a proven history of dengue infection (based on an antibody test or laboratory documentation of past dengue infection) are eligible for vaccination. The decision to implement a pre-vaccination screening strategy should be made after carefully assessing the country situation, including the sensitivity and specificity of available tests, as well as local priorities, the epidemiology of dengue, country hospitalization rates for dengue, and the affordability of both CYD-TDV and screening tests.

Vaccination should be considered as part of a comprehensive dengue prevention and control strategy. It does not replace the need to constantly take other disease prevention measures, in particular to conduct properly organized and targeted control of infection vectors. People who experience dengue-like symptoms should seek immediate medical attention, whether they have been vaccinated or not.

Evacuation from Koh Lipe to Hat Yai Hospital

There was no improvement. The three of us (Sergei, the doctor and I) struggled mentally with doubts about the necessary difficult evacuation and the progress of recovery. The sea was stormy.

The turning point came on January 1st. The temperature dropped to 38, but along with it the pressure and platelet level in the blood dropped to a critical level of 30 thousand (it was 150).

There was a threat of internal bleeding. Evacuation turned out to be inevitable. The speedboat was ordered, but they were waiting for the weather and tide. Another sleepless night and the morning of January 2 came.

The doctor himself arrived in Akira at 6.30 am to examine the patient and took another blood test. There was little hope of staying on Koh Lipe. But platelets dropped even lower overnight.

The speedboat picked us up right outside the Akira Hotel. We left our things at the hotel, hoping to return in a couple of days and continue our vacation on the island.

The doctor's assistant went with us on a speedboat to Pakbara. On the way, the speedboat rocked strongly and blood vessels on Sergei’s legs began to burst from the load - his legs began to turn black.

Dengue prevention and control

Patients with established dengue should avoid further mosquito bites during the first week of illness. During this time, the virus can circulate in the blood and the patient can transmit the virus to other uninfected mosquitoes, which in turn can infect other people.

One of the most important risk factors for contracting dengue and other infections transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes is the proximity of mosquito breeding sites to human habitats. Currently, the main way to contain or prevent the transmission of the dengue virus is to control the mosquitoes that carry it. This is achieved through the following measures:

- preventing mosquito breeding: preventing mosquitoes from accessing egg-laying sites by designing and modifying environmental facilities;

- Proper disposal of solid waste and destruction of man-made objects that may retain water and provide mosquito habitat;

- storing water supplies in closed containers indoors and emptying and washing containers weekly;

- treating outdoor water storage containers with suitable insecticides;

- Personal protection against mosquito bites: use of personal household protection such as window mosquito nets, repellents, insecticide-treated materials, coils and vaporizers. These measures need to be taken during the day, both inside and outside the home (for example, at work/school), since mosquitoes, which are the main vectors of infection, bite throughout the day;

- wearing clothing that covers the skin as much as possible, protecting it from mosquito bites;

- community outreach: informing the public about the risks associated with mosquito-borne diseases;

- interaction with the public for more active and targeted involvement of the population in the systematic fight against vectors of infection;

- Reactive vector control measures: Public health authorities can implement emergency vector control measures, such as indoor spraying of insecticides during disease outbreaks;

- active surveillance of mosquitoes and the virus: to determine the effectiveness of vector control activities, active monitoring and surveillance of their species abundance and composition is necessary;

- Prospective monitoring of virus prevalence among mosquito populations should be undertaken based on active screening of mosquito indicator collections;

In addition, many groups of international partners continue to conduct research to find new tools and innovative strategies that will contribute to global efforts to stop the transmission of dengue, as well as other mosquito-borne diseases. WHO encourages the integrated use of different vector control approaches to ensure the continuity and effectiveness of locally tailored vector control interventions.

WHO activities

WHO's response to dengue is as follows:

- assisting countries in confirming outbreaks through a network of collaborating laboratories;

- providing countries with technical support and guidance to effectively control dengue outbreaks;

- helping countries improve reporting systems and recording the true burden of disease;

- providing specialized training in clinical management, diagnosis and vector control at country and regional levels in collaboration with a number of WHO collaborating centres;

- developing evidence-based strategies and policies;

- supporting countries in developing dengue prevention and control strategies and implementing the Global Vector Control Action (2017–2030);

- conducting reviews of new disease control tools, including insecticides and technologies for their use;

- collection of official data on dengue and severe dengue from more than 100 Member States; And

- publication of recommendations and manuals for Member States on surveillance, patient care, diagnosis, prevention and control of dengue.