Key Facts

- Taeniasis is an intestinal parasitic infection caused by tapeworms. The causative agents of taeniasis in humans are three types of parasites. These are Taenia solium, Taenia saginata and Taenia asiatica. Only T. solium poses a serious health hazard.

- Human infection with T. solium occurs as a result of the ingestion of parasite larvae (cysticerci) by eating pork infected with them that has not undergone proper heat treatment.

- Tapeworm eggs are shed in the feces of tapeworm carriers and contaminate the environment if they defecate in unprotected areas.

- Infection with T. solium eggs is also caused by poor personal hygiene (infection through the fecal-oral route) or consumption of contaminated food or water.

- Ingested T. solium eggs hatch into larvae (called cysticerci) that migrate to a number of internal organs. If they enter the central nervous system, they can lead to the development of neurological symptoms (neurocysticercosis), including epileptic seizures.

- T. solium is responsible for 30% of epilepsy cases in many endemic areas where pigs are free-ranged in close proximity to human habitation. In high-risk settings, 70% of epilepsy cases may be associated with T. solium infection.

- More than 80% of the 50 million people with epilepsy worldwide live in low- and lower-middle-income countries.

Mechanism of transmission and burden of disease

Taeniasis is an intestinal parasitic infection caused by three species of tapeworms: Taenia solium (pork tapeworm), Taenia saginata (bovine tapeworm) and Taenia asiatica.

Infection with T. saginata or T. asiatica occurs through consumption of inadequately cooked contaminated beef or pork liver, respectively, but taeniasis caused by T. saginata or T. asiatica does not pose a serious risk to human health. Therefore, this fact sheet focuses only on T. solium, its mechanisms of transmission and its impact on health.

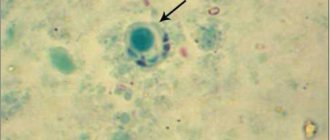

T. solium tapeworm infection is caused by eating raw or undercooked pork. Infection with T. solium causes few clinical symptoms. Tapeworm eggs present in the feces of a tapeworm carrier can infect pigs. T. solium eggs can also enter the human body (through the fecal-oral route or through consumption of contaminated food or water), causing tissue infection by parasite larvae (human cysticercosis).

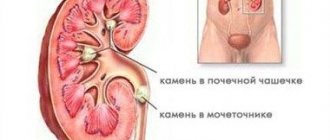

Cysticercosis can cause extremely serious health consequences. Flatworm larvae (cysticerci) are able to develop in muscles, skin, eyes and the central nervous system. If larvae develop in the brain, neurocysticercosis (NCC) develops. Its symptoms include severe headaches, blindness, convulsions and epileptic seizures and can lead to death.

NCC is the most common preventable cause of epilepsy worldwide and is estimated to account for 30% of all cases of epilepsy in endemic countries. In some communities, 70% of epilepsy cases may be associated with neurocysticercosis. In poor and remote areas where the disease is common, diagnostic and treatment options for epilepsy are extremely limited, which creates conditions for significant stigmatization of patients, especially girls and women (as epilepsy is often associated with witchcraft).

Cysticercosis is a major health and well-being problem for members of subsistence farming communities in developing countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. It also reduces the market value of pork and makes pork unsafe to eat.

In 2015, the WHO Reference Group on the Epidemiology of the Burden of Foodborne Diseases recognized T. solium as one of the leading causes of death from foodborne illnesses, with the disease burden estimated at 2.8 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). The total number of people affected by NCC, including both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases, is estimated to range from 2.56 million to 8.3 million based on available data on the prevalence range of epilepsy.

Although 70% of patients with epilepsy could lead a normal life with proper treatment, due to poverty, lack of information about the disease, poor health infrastructure or lack of access to medicines, 75% of patients receive poor or no treatment.

Symptoms

Symptoms of taeniasis caused by T. solium, T. saginata or T. asiatica are usually mild and nonspecific. Approximately eight weeks after eating meat containing cysticerci, the tapeworms have fully developed in the intestines, and the patient may experience abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, or constipation.

These symptoms may persist until the worms are killed by treatment. Otherwise, they can live in the body for many years. If untreated, helminthic infestations caused by T. solium tapeworms are thought to typically last about 2–3 years.

The incubation period for cysticercosis due to T. solium infection varies, and the disease may remain asymptomatic for many years. In some endemic areas (especially in Asia), infected people may develop visible or palpable nodules under the skin.

Neurocysticercosis is characterized by the occurrence of a number of symptoms and clinical signs depending on the number, size, stage and localization of pathological changes, as well as on the immune response of the host, although sometimes it can be asymptomatic. Possible symptoms include chronic headaches, blindness, seizures (epilepsy if the attacks are regular), hydrocephalus, meningitis and symptoms caused by the presence of lesions in the cavities of the central nervous system.

Taeniasis/cysticercosis

Key facts:

- Taeniasis is an intestinal infection caused by adult tapeworms.

- The causative agent of taeniasis in humans can be one of three types of tapeworms: Taenia solium, Taenia saginata and Taenia asiatica. Only T. solium can cause serious health problems.

- Human infection with T. solium occurs as a result of tapeworm larvae (cysticerci) entering the gastrointestinal tract when eating pork that has not undergone proper heat treatment.

- Tapeworm eggs are shed in the stool of an infected person and, in cases of open defecation, are released into the environment.

- A person can also become infected with T. solium eggs as a result of consuming contaminated food or water (human cysticercosis) or poor personal hygiene

- The eggs that enter the human body hatch into larvae (called cysticerci), which are then spread throughout the body. If they enter the central nervous system, they can lead to the development of neurological symptoms (neurocysticercosis), including epileptic seizures.

- T. solium infection is responsible for 30% of epilepsy cases in many endemic areas where stray pigs live in close proximity to human habitation.

- Globally, more than 80% of the 50 million people with epilepsy live in low- and lower-middle-income countries.

- There is a set of control and preventive measures, the practical implementation of which depends on the local context and resource availability.

Transmission of infection and burden of morbidity.

Taeniasis is an intestinal infection that can be caused by 3 types of tapeworms: Taenia solium (pork tapeworm), Taenia saginata (bovine tapeworm) and Taenia asiatica.

A person can become infected with T. saginata or T. asiatica by eating undercooked contaminated beef or pork liver, respectively, but taeniasis caused by T. saginata or T. asiatica does not have serious negative consequences for human health. Therefore, this fact sheet focuses exclusively on the transmission of T. solium and the health harm it causes.

Human infection with T. solium occurs as a result of eating raw or improperly cooked contaminated pork. Tapeworm eggs leave the body in the feces and can cause infection in pigs. Human infection caused by T. solium tapeworms is almost asymptomatic. However, as with pigs, humans can also become infected with T. solium eggs through ingestion, which can lead to parasitic tissue infection (human cysticercosis).

This infection can lead to catastrophic consequences for human health. Flatworm larvae (cysticerci) can inhabit muscles, skin, eyes and the central nervous system. When cysts appear in the brain, the disease is called neurocysticercosis. Symptoms include severe headaches, blindness, convulsions and epileptic seizures. The disease can lead to the death of the patient. Neurocysticercosis is the most common preventable cause of epilepsy worldwide. It is estimated that this disease accounts for 30% of all cases of epilepsy in endemic countries.

Cysticercosis primarily affects the health and livelihoods of subsistence communities in developing countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. It also causes the market price of pigs and cattle to fall and makes the consumption of pork dangerous.

In 2015, the WHO Epidemiological Reference Group for Estimating the Burden of Foodborne Diseases recognized T. solium as the leading cause of death from foodborne illnesses, with a burden estimated at 2.8 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). The total number of people with neurocysticercosis, including symptomatic and asymptomatic cases, is estimated to range from 2.56 to 8.3 million, depending on available sources of epilepsy prevalence data.

In 2010, cysticercosis caused by T. solium was included in the WHO list of the most important neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). The NTD Roadmap set goals for developing a science-based strategy for the control and elimination of T. solium taeniosis/cysticercosis and scaling up interventions in selected countries by 2021.

Symptoms.

Symptoms of taeniasis caused by T. solium, T. saginata or T. asiatica are usually mild and nonspecific. Approximately 8 weeks after eating meat containing cysticerci, when the tapeworms have fully developed in the intestines, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea or constipation may occur.

These symptoms may persist until the worms die as a result of treatment. Otherwise, they can live for many years. Untreated infections caused by T. solium worms are thought to typically last 2-3 years.

In the case of cysticercosis caused by T. solium, the length of the incubation period before symptoms appear may vary, and infected individuals may remain asymptomatic for several years.

In some endemic areas (especially Asia), infected people may develop visible or palpable nodules (small, hard bumps or lumps) under the skin. Neurocysticercosis is characterized by a variety of symptoms and signs depending on the number, size, stage and location of pathological changes, as well as the immune response of the host. It may also occur without clinical symptoms. Symptoms may include chronic headache, blindness, seizures (epilepsy if recurrent), hydrocephalus, meningitis, dementia, and symptoms caused by lesions in the central nervous system.

Treatment.

To treat taeniasis, praziquantel (5-10 mg/kg, single dose) or niclosamide (adults and children over 6 years of age: 2 g, single dose after a light meal, followed by a laxative two hours later; children aged 2-6 years) are prescribed : 1 g; children under two years old: 500 mg).

Because cyst destruction may cause an inflammatory response, long-term use of praziquantel and/or albendazole in combination with supportive care with corticosteroids and/or antiepileptic drugs may be chosen to treat active neurocysticercosis, and in some cases surgery may be indicated. The dosage and duration of treatment can be very different and depend mainly on the number, size, location and stage of development of cysts, the presence of inflammatory edema at their locations, the severity and severity of clinical symptoms and signs.

Control and preventive measures

Prevention, control and potential eradication of T. solium requires appropriate public health interventions covering animal health, human health and the environment. For T. solium, different combinations of eight types of control and prevention activities can be carried out depending on the conditions in specific countries:

- Mass prescription of drugs against taeniasis;

- Detection and treatment of cases of taeniasis;

- Health education, including on hygiene and food safety;

- Sanitation;

- Improved pig farming practices;

- Anthelmintic treatment for pigs (oxfendazole at a dosage of 30 mg/kg is a commercially available and registered drug for the treatment of cysticercosis in pigs);

- Vaccination of pigs (TSOL18 vaccine – available on the market);

- Strengthening veterinary and sanitary control of meat and meat processing.

There remains a lack of reliable epidemiological data on the geographic distribution of T. solium taeniasis and cysticercosis in humans and pigs.

Establishing appropriate surveillance mechanisms could enable the recording of new cases of cysticercosis in humans and pigs, allowing local communities at high risk to be identified and control measures implemented in identified areas.

The role of WHO.

Working with veterinary and food safety authorities and other sectors will be essential to achieving the long-term ultimate goal of reducing the disease burden and protecting the food supply chain.

The WHO Neglected Tropical Diseases Program works closely with other WHO departments in the areas of mental health, research and development, food safety, safe water and sanitation, and with partner agencies such as the Food and Agriculture Organization United Nations (FAO) and the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) to ensure the necessary interdisciplinary cooperation to combat T. solium. The ultimate goal of this activity is to prevent human suffering as a result of neurocysticercosis.

To address the need for clear guidance on a stepwise approach to developing control programmes, WHO has already taken the first steps with countries and key partners to find the most suitable strategy to interrupt T. solium transmission and improve the diagnosis and management of neurocysticercosis using currently available tools .

There remains a need for improved, simpler, and lower cost rapid diagnostic tools suitable for use in the field to detect T. solium carriers and cases of human and porcine cysticercosis, as well as for program planning and monitoring. In December 2015, a stakeholder meeting on the diagnosis of taeniasis/cysticercosis due to T. solium was held at WHO headquarters. The topic of the meeting was the problem of the lack of suitable tools for diagnosing taeniasis, cysticercosis and neurocysticercosis.

WHO's Neglected Tropical Diseases and Mental Health programs are also leading the development of evidence-based standard guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of T. solium cysticercosis to support clinical management and inform national programs and policies.

A number of countries are preparing pilot programs based on existing tools, while simultaneously conducting operational research to measure impact and adjust strategies. More and more countries are interested in joining the WHO taeniasis/cysticercosis control network.

A critical element needed to assess disease burden and progress is the generation of reliable surveillance data. As with other neglected tropical diseases that occur among health-poor populations in remote areas, statistics are particularly lacking. WHO is trying to correct this situation by producing epidemiological maps of the prevalence of T. solium infection based on data on associated risk factors, including information on pig production, food safety and sanitation.

(according to the official WHO website - https://www.who.int).

Treatment

An important measure to prevent NCC and combat the spread of the parasite is the treatment of taeniasis caused by Taenia solium. Treatment of persons with this parasitic infestation can be individual or carried out as part of preventive chemotherapy, depending on local conditions and the methods used to combat the disease. To treat taeniasis, a single dose of praziquantel (10 mg/kg) or niclosamide is prescribed (adults and children over 6 years old - 2 g; children aged 2-6 years - 1 g). Albendazole can also be prescribed at a dosage of 400 mg/day for 3 consecutive days[1].

In patients with neurocysticercosis, the destruction of cysts can cause an inflammatory response, so treatment requires specific therapy, which may include long-term administration of high-dose praziquantel and/or albendazole in combination with maintenance therapy with corticosteroids and/or antiepileptic drugs and, in some cases, surgery . The dosage and duration of drug treatment can be very different and depend mainly on the number, size, location and stage of development of cysts, the presence of inflammatory edema at their location, the severity and severity of clinical symptoms and signs [2].

Clinical picture of taeniosis

The harmful effect of the parasite is formed from mechanical effects, consumption of the host’s food, and the toxic effect of the worm’s waste products on the human body. As a result, the signs of taeniasis can be quite diverse, but nonspecific.

The initial symptoms of invasion begin to appear in humans only in the chronic phase, when the tapeworm grows into a sexually mature individual. Patients complain of weakness, increased irritability, and appetite disorders. At the beginning of the disease, appetite increases very strongly, up to bulimia (craving to overeat), while the patient’s weight does not increase, but even decreases; over time, appetite decreases, and the person’s weight returns to normal and does not change significantly in the future.

Patients experience pain in different halves of the abdomen. Particularly common in the right iliac region, when proglottids pass through the receptor-rich ileocecal valve (Bauhinian valve), separating the small and large intestines.

Patients are concerned about nausea, vomiting, rumbling in the abdomen, flatulence (painful bloating), and periodic increased frequency of stools. Many patients complain of the presence of helminth segments in the feces. Some patients experience glossitis (inflammation of the tongue).

In persons with weakened immune systems, neurological disorders, headache, dizziness, fainting, sleep disturbances, and sometimes convulsive seizures may occur. At later stages during the life of the worm, the infected person develops allergic skin lesions in the form of urticaria.

A severe and dangerous complication of taeniasis is cysticercosis, when the Finnish stage of the helminth develops in the human body, turning the patient into an intermediate host. A person suffering from pork tapeworm is always at risk of developing cysticercosis!

Prevention and control

Prevention, control and potential elimination of T. solium requires public health interventions in areas such as veterinary, public health and the environment. There are a number of interventions to control T. solium, which can be implemented in different combinations. At the expert meeting held in 2009, the following list of activities was compiled:

Key activities to get quick results:

- treatment of patients with taeniasis;

- interventions in pig populations (vaccination and anthelmintic treatment);

Supporting activities:

- health education of the local population, including on hygiene and food safety;

- improving sanitation conditions - stopping the practice of defecation in unequipped places;

Measures that require deeper social change:

- improved pig farming practices (elimination of free-range pigs);

- strengthening veterinary and sanitary control of meat and improving methods of processing meat products.

In order to determine the likelihood of success of different combinations of measures, as well as the duration of their implementation period sufficient to obtain a sustainable result, mathematical models are used, but these models are still based on numerous assumptions and assumptions. However, the results from these models tend to agree that integrated One Health interventions are more likely and faster to produce sustainable results in disease control.

WHO activities

Promoting more effective management of patients with neurocysticercosis

One of the most common clinical signs in patients with neurocysticercosis (NCC) is epilepsy. WHO recognizes that people with epilepsy are often subject to stigma and discrimination. WHO urges Member States to support the development and implementation of epilepsy care strategies and to promote interventions aimed at preventing the causes of epilepsy (resolution WHA68.20 (2015)). To promote improved clinical management, WHO has published guidelines for the care of patients with neurocysticercosis caused by Taenia solium.

Providing advice on developing better diagnostic tools and supporting countries to build diagnostic capacity

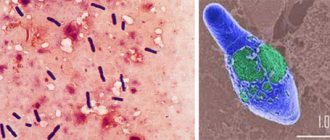

Fecal screening tests, particularly the Kato-Katz method, can be used to detect Taenia eggs and therefore areas that may be endemic for the parasite, but this test is not species specific and requires confirmation of positive specimens for T. solium.

Imaging is the gold standard for diagnosing NCC, but there remains a need to develop better, easier-to-use, and lower-cost diagnostic tools for Taenia solium infestation. WHO has developed targeted product profiles (TPPs) for diagnostics for NCC, taeniasis and porcine cysticercosis, which were published in 2021.

Supporting countries in their efforts to control cysticercosis

Countries affected by cysticercosis are calling on WHO to support their work to control the disease. Below are some of the measures taken.

Identification (mapping) of endemic areas. One of the first steps to control the disease is to identify communities or endemic areas that should be targeted. WHO has developed an area listing protocol that includes an Excel tool to assess risk levels and identify areas at high risk of T. solium endemicity.

Free supplies of drugs to combat tapeworms. As part of universal health coverage and to ensure access to quality medicines, WHO has entered into a donation agreement with two tapeworm control drugs, which are now available through WHO for T. solium control programmes.

Support the development of validated programs to control T. solium. A number of countries are implementing pilot programs, accompanied by observational studies to assess their effectiveness and refine strategies; an example is the pilot project in Madagascar.

Issue recommendations for the implementation of taeniasis control programs. In the Region of the Americas, PAHO published a guide: Practical aspects for the control of taeniasis and cysticercosis caused by Taenia solium - a contribution to the control of T. solium in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Strengthening control and prevention measures based on the One Health approach

During the life cycle of T. solium, pigs act as intermediate hosts for the parasite. As part of a comprehensive strategy to interrupt the transmission cycle of the parasite, it is important to take measures to control taeniasis in pigs.

Promote a multi-sectoral approach involving key partners. Through the Tripartite Partnership, WHO works closely with partner organizations such as the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) to promote veterinary interventions and promote interdisciplinary collaboration in the control of T. solium with the ultimate goal of preventing human suffering caused by NCC.

Assistance in carrying out veterinary activities. Specific control interventions in pig populations include the introduction of good agricultural practices, vaccination of pigs with the TSOL18 vaccine, and treatment of pigs with oxfendazole. Vaccination protects pigs from infection by parasites, and oxfendazole allows you to cure animals infested at the time of vaccination, and both of these measures can be combined. In collaboration with veterinary authorities, as well as key partners in the livestock sector, WHO is supporting pilot projects to implement control measures in pig populations needed to achieve long-term sustainable results.

Differences between pork tapeworm and bovine tapeworm

Bull tapeworm is also a representative of tapeworms. It has a long lifespan and its body can reach a length of up to 10 meters, while the armed tapeworm does not grow to more than 4 meters. However, adult pork tapeworms are capable of active movement and more severe damage to the host's intestinal mucosa due to teeth and suckers, which are absent in their relatives. Therefore, infection with bovine tapeworm (teniarchosis) is less dangerous for humans and is easier to treat.

Life cycle and epidemiology

The lifespan of a pork tapeworm is more than 10 years. The main characteristic of its life cycle is isolation; several hosts are required for the development of worms. The intermediate host, as a rule, is pigs and wild boars, less often dogs and cats. Together with the food, the animal absorbs helminth eggs, which transform into larvae (oncospheres) in the intestines of the host. Soon, oncospheres spread throughout the body through the bloodstream, settling in organs and tissues. Are there 2 each? After 2.5 months, cysticerci are formed - small larval vesicles containing the scolex of the future worm - the invasive stage of development of the parasite begins.

Humans are the definitive host of the worm. You can become infected with pork tapeworm by eating meat infected with cysticerci that has not undergone sufficient heat treatment. After the scolex worm enters the human body, it is attached to the intestinal wall with the help of teeth and suction cups, and after 2-4 months a sexually mature individual is formed from it. The eggs of the parasite are released into the environment with feces and end up in the food of animals. Thus the cycle begins again.

The armed tapeworm is a hermaphrodite; one segment can contain up to 50,000 eggs. Therefore, there are cases where several parasites were found in one host.

Improving the quality of epidemiological data on T. solium

The availability of reliable epidemiological data is fundamental to assessing the burden of disease, implementing disease control measures and assessing their impact. As with other neglected diseases, such data are extremely limited. WHO is actively collecting and analyzing data on the geographic range and risk factors for the spread of T. solium, including data on the size and characteristics of pig production, food safety and sanitation. This information is reported to the WHO Global Health Observatory.

[1] Recommendations and important guidelines for the use of these drugs for preventive chemotherapy are provided in the WHO/PAHO Guidelines for the management of preventive chemotherapy for the control of taeniasis caused by T. solium.

[2] More detailed information for health care providers is provided in the WHO guidelines for the management of taeniasis caused by T. solium.