Heartburn and related symptoms

The general clinical picture will help determine a preliminary diagnosis and conduct only the necessary studies.

Heartburn 15-20 minutes after eating is the result of dietary errors or stomach diseases. After eating, an “acid pocket” forms in the upper part of the stomach; from this reservoir, the contents flow back into the esophagus. With hyperacid gastritis, heartburn is accompanied by sharp pain in the epigastrium. With hypoacid gastritis, the pain is dull, often combined with constipation and bloating.

Heartburn before or at the beginning of a meal is gastroesophageal reflux.

Heartburn with bile indicates pathology of the liver and gallbladder. A burning sensation in the esophagus occurs 30 minutes to 2 hours after eating, driving or cycling and is accompanied by heaviness/pain in the right hypochondrium.

Heartburn after a course of antibiotics - a violation of the microflora (dysbacteriosis) provokes increased gas formation and an increase in intra-abdominal pressure.

Heartburn and bitterness in the mouth in the morning are the result of overeating at night, following a strict diet for weight loss, and eating “provoking” foods.

Heartburn and diarrhea (diarrhea) are signs of an inflammatory process in the gastrointestinal tract. Body temperature often rises.

Heartburn and bloating - consumption of coarse fiber, overeating, dysbiosis, chronic constipation, intolerance to dairy products.

Cough with heartburn - GERD, smoker's bronchitis.

Heartburn, nausea and vomiting - gastritis, ulcers and erosions of the stomach, side effects of medication. drugs, stomach cancer.

Heartburn, dizziness and weakness - gastrointestinal disease is combined with anemia/hypotension. The sudden appearance of painful symptoms may indicate a hypertensive crisis or developing myocardial infarction. Antacids don't help.

Heartburn and belching - occurs when eating avidly, talking while eating, or a hiatal hernia.

Gastrointestinal pathology in outpatient practice

Diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. Main syndromes, differential diagnosis, clinical and prognostic significance: heartburn, belching, nausea and vomiting

Authors: Ph.D., Associate Professor.

Sedyakina Yu.V., Volkova A.S. Key words: gastrointestinal tract, heartburn, belching, nausea, vomiting.

Summary: the article examines the most common symptoms of gastrointestinal diseases.

Heartburn

Functional heartburn

Roman IVs? Criteria for functional heartburn:

- Retrosternal burning or pain.

- No improvement with optimal antisecretory therapy.

- There is no evidence that gastroesophageal reflux or eosinophilic esophagitis is the cause of symptoms.

- Absence of pronounced esophageal motor disorders (obstruction, etc.).

Eligibility must occur if symptoms have been present for 3 months from their onset, at least 6 months before diagnosis.

Red flags

- Dysphagia - difficulty swallowing

- Odynophagia - painful swallowing

- Recurrent bronchial symptoms, aspiration pneumonia

- Dysphonia, recurrent cough

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- Microcytic anemia

- Progressive unplanned weight loss

- Lymphadenopathy

- Education in epigastrium

- Onset of heartburn at ages >50–55 years

- Family history of esophageal adenocarcinoma

Patient with heartburn symptom at outpatient appointment

“Boris Timofeich ate mushrooms and gruel at night, and he began to have heartburn; suddenly there was a feeling in the pit of his stomach..."

N.S. Leskov. Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk

“Nikolai Andreevich Kapitonov, a notary, had lunch, smoked a cigar and went to his bedroom to rest. He lay down, covered himself from the mosquitoes with muslin and closed his eyes, but could not sleep. The onion he ate along with the okroshka gave him such heartburn that he couldn’t even think about sleep.”

A.P. Chekhov. With nothing to do. Story. Fragments. 1886.

Three mechanisms to protect the esophageal mucosa from the effects of reflux:

- Mechanical cleaning

- Normalization of pH value

- Barrier properties of the epithelial lining of the esophagus

Causes of reflux:

- Factors that reduce pressure at the level of the lower esophageal sphincter

- Frequent temporary opening of the sphincter

- Decrease in mechanical cleaning efficiency

- Reducing the speed of normalization of the pH value

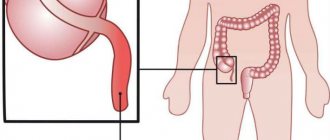

- Hiatal hernia

- Direct irritation and damage to the esophageal mucosa

Causes of heartburn

- Delayed gastric evacuation

- Impaired gastric accommodation controlled by the vagal reflex

- Gastric and duodenal hypersensitivity to distension, acid and other intracavitary stimuli

- Impaired permeability of the gastrointestinal mucosa

- Possibly H. pylori

- Psychosocial factors

IF ANY OF THESE DRUGS HAVE BEEN TAKEN, THE PATIENT SHOULD STOP THEM:

- NSAIDs, glucocorticosteroids

- Antimicrobial agents (macrolides, sulfonamides, metronidazole)

- Cardiac glycosides

- Nitrates

- Loop diuretics

- ACEI

- Calcium channel blockers

- Iron supplements

- Bisphosphonates

- Anticholinergics, alpha-adrenergic antagonists, barbiturates

- β2-adrenergic agonists, benzodiazepines, dopamine

- Estrogens, narcotic analgesics, progesterone

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), chemotherapy

DIAGNOSIS:

- Symptoms, duration, frequency, remedies

- Patient history

- Medicines taken

- Warning signs

CONTROL:

- Routine endoscopy is not needed in patients without warning signs.

- Urgent endoscopy is recommended for patients over 55 years of age with unexplained, persistent, recent-onset heartburn.

- Early endoscopy may be considered in geographic areas where the incidence of esophageal and gastric cancer is high.

- Compliance with dietary recommendations by the patient.

- Evaluation of response to treatment with gastroprotectors.

OBSERVATION:

- Patients with warning signs should be offered an annual examination.

Self-help for heartburn:

- Antacids—recommended for short-term or intermittent relief.

- Alginate-containing preparations.

- PPI - the effect lasts up to 24 hours.

Triggers: identify the most common trigger substances and behaviors; Avoiding these triggers will reduce your risk of developing acid reflux symptoms.

Lifestyle changes:

- Weight loss.

- Avoid consumption of nicotine, coffee, alcohol, carbonated drinks, chocolate, mint, fried or fatty foods, citrus fruits or their juices, tomato products, garlic or onions, and spicy foods.

- Eat smaller portions more frequently.

- Raise the head of the bed by 20–25 cm.

- Avoid eating and drinking within 3 hours before bedtime.

Treatment:

I line

- Lifestyle change

- Dietary recommendations

- Gastroprotectors (PPIs, etc.)

- Prokinetics (dompiredone, itopride, etc.)

II line

- Antidepressants (buspirpone, sumatriptan, etc.)

Patient I., 38 years old, was hospitalized in a multidisciplinary hospital on August 13, 2020 by an emergency medical team with a referral diagnosis of acute cholecystitis.

She notes periodic pain in the epigastrium, nausea, belching, bitterness in the mouth (increasing in the morning), regurgitation of food when bending over, in a horizontal position. The above complaints have been bothering me for 2 years. I periodically took omeprazole and almagel with a short-term positive effect. After discontinuation of therapy, the complaints returned again.

Objectively: The general condition is of moderate severity, due to pain. Increased nutrition. Auscultation over the entire surface of the lungs reveals vesicular breathing, without wheezing, respiratory rate = 18 per minute. On auscultation: heart sounds are preserved, the rhythm is correct, heart rate = Ps = 72, blood pressure 120/80 mmHg. The abdomen is not enlarged, auscultation: peristalsis is preserved; soft and slightly painful on palpation. The liver and spleen are not palpable.

Consultation with a surgeon: there is no evidence of acute surgical pathology.

| Index | 13.08.20 | Index | 13.08.20 |

| Red blood cells | 4,50 | Albumen | 44 |

| Hemoglobin | 120 | Creatinine | 70 |

| MCV | 90,0 | Bilirubin total | 20 |

| Leukocytes | 4,2 | Cholesterol total | 3,0 |

| Platelets | 190 | Urea | 5,9 |

| ESR | 12 | Glucose | 5,0 |

An endoscopy was performed. Conclusion: endoscopic signs of axial hiatal hernia. Distal chronic nonerosive esophagitis. Focal gastritis.

An x-ray was also performed, which also confirmed gastroesophageal reflux.

An ultrasound scan of the obstructive system was performed; the pancreas, liver, and gallbladder were normal and without pathology.

Treatment:

- PPI 2 times a day

- Prokinetics 3 times a day

- Gastroprotectors

After 14 days, positive dynamics: reduction in heartburn, belching of air (clinically), pain syndrome was relieved.

EGDS control: the mucous membrane of the esophagus in the abdominal section is physiologically colored, there is no swelling, the cardia does not close completely.

Algori

Belching

Belching is defined as the audible release of air from the esophagus or stomach through the pharynx.

Belching is considered a disorder when it is bothersome.

Supragastric (supragastric)

- Belching is characterized by rapid antegrade and retrograde movement of air into the esophagus, which usually does not reach the stomach.

- Air enters the esophagus through the pharynx and is immediately expelled into the oral cavity.

Stomach (gastric)

- The release of air due to relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter.

* The term “aerophagy” is considered erroneous and is considered only in historical terms.

Rome IV criteria for belching:

- Troubling (i.e., intensity is such that it reduces normal activity) belching from the esophagus or stomach more than three days a week.

Eligibility must occur if symptoms have been present for 3 months from their onset, at least 6 months before diagnosis.

Red flags:

- Dysphagia - difficulty swallowing

- Odynophagia - painful swallowing

- Recurrent bronchial symptoms, aspiration pneumonia

- Dysphonia, recurrent cough

- Microcytic anemia

- Progressive unplanned weight loss

- Lymphadenopathy

- Family history of esophageal adenocarcinoma

Causes:

- GERD

- Peptic ulcer of the stomach and duodenum

- Obsessive-compulsive disorders

- Bulimia

- Abdominal abscess

- ACS (myocardial infarction, etc.)

- Obstruction (obstruction) of the digestive tract

Diagnostics:

- ECG

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- RN-impedancemetry

Additionally

- Ultrasound of the abdominal organs

Nausea and vomiting

NAUSEA is a subjective symptom and can be defined as an unpleasant sensation of an impending need to vomit, usually experienced in the epigastrium or throat.

VOMITING is a complex reflex involving both autonomic and somatic nerve pathways; synchronous contraction of the diaphragm, intercostal muscles and abdominal muscles increases intra-abdominal pressure and, in combination with relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, leads to the forced ejection of stomach contents.

- The center of vomiting is located in the lateral part of the reticular formation near the tractus solitarius.

- All afferent flows from the pharynx, gastrointestinal tract, mediastinum, from the visual thalamus, the vestibular apparatus of the VIII pair of cranial nerves and the trigger (starting) zone of chemoreceptors, which is located in the area postrema of the brain stem, are sent here.

The vomiting center is stimulated

- with direct pressure on it (Hp with a brain tumor);

- through the blood (Hp with subcutaneous administration of apomorphine);

- with the accumulation of various metabolic products in the blood, with exo/endotoxicosis and autointoxication (hyperazotemia, ketoacidosis, hypoxia, metabolic disorders, hypotension, etc.).

Pathogenesis

- nausea and vomiting can be caused by stimuli originating from visceral, vestibular and chemoreceptor trigger areas and mediated by serotonin, dopamine, histamine and acetylcholine neurotransmitters.

- The receptors thought to be involved in nausea and vomiting vary depending on the specific cause:

- gastroenteritis - dopamine and serotonin;

- motion sickness and vestibular disorders - histamine and acetylcholine;

- nausea associated with migraine - dopamine.

Rome IV criteria for nausea and vomiting:

Chronic Nausea and Vomiting Syndrome

- Worrying (i.e., intensity is such that it reduces normal activity) nausea occurring at least 1 time per week and/or 1 or more episodes of vomiting per week.

- Must be excluded: spontaneous induction of vomiting by the patient, eating disorder, regurgitation and rumination.

- There is no evidence based on routine examination (including upper endoscopy) of the presence of organic, systemic or metabolic diseases that could explain these symptoms.

Eligibility must occur if symptoms have been present for 3 months from their onset, at least 6 months before diagnosis.

Rome IV criteria for nausea and vomiting:

Cyclic vomiting syndrome

- Episodes of vomiting that are stereotypical in onset (acute) and duration (less than 1 week).

- At least 3 separate episodes in the previous year and 2 episodes in the last 6 months. with an interval of at least 1 week.

- No vomiting between episodes. But other milder symptoms may have been present.

Supporting Criteria

- The patient has a history or family history of migraine with headache.

Eligibility must occur if symptoms have been present for 3 months from their onset, at least 6 months before diagnosis.

Cannabinoid hyperemetic syndrome

Nausea and vomiting. Red flags

- Stomach ache

- Fever

- Diarrhea

- Relationship with food and drug use

- Headache

- Weight loss

Causes:

- Psychogenic

- Diseases of the central nervous system (migraine, increased intracranial pressure, meningitis)

- Acute abdominal syndrome (appendicitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, intestinal obstruction)

- Uremia

- Alcoholic polyvisceropathy

- Infections (gastroenteritis, hepatitis, urinary tract infections)

- Metabolic (diabetic ketoacidosis, Addison's disease, cyclic vomiting syndrome)

- Medicines (NSAIDs, opiates, Digoxin, antibiotics, cytotoxins)

- Pregnancy

Infections:

- most often

- bacterial or viral gastroenteritis

- food poisoning

- pyelonephritis

- encephalitis

- brain abscess

- meningitis

- pneumonia

Gastrointestinal causes:

- common reasons

- appendicitis

- cholecystitis

- cholelithiasis

- large/small bowel obstruction

- acute gastritis

- gastroesophageal reflux disease

- gastroparesis

- peptic ulcer of the stomach and/or duodenum

- pancreatitis

- adhesive disease of the abdominal organs

- achalasia of the esophagus

- strangulated hernia

- mesenteric ischemia

- bacterial peritonitis

- Crohn's disease

- functional dyspepsia

- malignant neoplasms of the upper gastrointestinal tract

Medicines:

- antiarrhythmic drugs

- digoxin

- antibacterial drugs

- anticonvulsants

- chemotherapy drugs

- oral antidiabetic drugs, especially metformin

- oral contraceptives

- sulfasalazine

- nicotine, including nicotine patches

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- opioids

- high doses of vitamins

CNS most common causes of acute vomiting

- migraine

- benign positional paroxysmal vertigo

- seasickness

less common causes

- increased intracranial pressure

- epilepsy

- cerebrovascular event

- closed craniocerebral injury

- hydrocephalus

- Meniere's disease

- meningitis

Endocrine and metabolic

- uremia

- diabetic ketoacidosis

- adrenal glands

- parathyroid glands

- thyroid diseases

Psychiatric causes:

- bulimia

- anorexia nervosa

- schizophrenia

- somatoform disorders

- hypochondria

- pain disorders

Other reasons

- myocardial infarction (often “lower” infarction)

- pregnancy

- ethanol abuse or overdose

- radiation therapy

- Nephrolithiasis

- cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (severe nausea, intractable vomiting and abdominal pain) associated with chronic heavy cannabis use

- postoperative nausea and vomiting

- exposure to toxins (arsenic, organophosphates, pesticides)

- use of mask anesthesia with nitrous oxide

- after laparoscopic operations in the abdominal cavity, performed using combined anesthesia with nitrous oxide.

The reasons for this lie in the toxic effect of nitrous oxide on the receptor apparatus of the vestibular zone, in changes in pressure in the middle ear, stretching of the receptor apparatus of the stomach and intestines due to the diffusion of gas into the “third space”.

The incidence of vomiting has not decreased with the use of newer inhaled halogen agents (isoflurane, enflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane).

Anamnesis

- duration of symptoms;

- exposure to toxins, suspect foods, and contact with sick people with nausea and vomiting;

- whether the onset was acute, which may indicate gastroenteritis, cholecystitis, drug effect or pancreatitis;

- associated diarrhea, headache and myalgia, which may indicate viral gastroenteritis;

- timing of vomiting compared with meals, with delayed vomiting (> 1 hour after meals) indicating gastric outlet obstruction or gastroparesis.

Characteristics of vomiting episodes

- vomiting of bile or relief of abdominal pain with vomiting, which may indicate small intestinal obstruction;

- regurgitation of undigested food may indicate achalasia, esophageal stricture, or Zenker's diverticulum;

- Acid regurgitation may indicate GERD.

Symptoms that require a decision on immediate hospitalization:

- acute abdominal pain, which may indicate appendicitis, pancreatitis, small bowel obstruction or acute cholecystitis;

- head injury or other trauma;

- black stool (melena), which may indicate gastrointestinal tract with erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastrointestinal tract;

- bloody stools (hematochezia), which may indicate colorectal cancer.

Symptoms of diseases of the urinary system:

- dysuria, increased frequency, or urge to urge may indicate pyelonephritis;

- decreased urine output may indicate hypovolemia.

Taking medications that cause nausea and vomiting:

- non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- iron

- digoxin

- opioids

- dopaminergic drugs (such as levodopa and bromocriptine)

- chemotherapy drugs

Objectively:

- in patients with prolonged or severe nausea and vomiting, skin turgor is reduced;

- dry mucous membranes;

- tachycardia;

- loss of tooth enamel may indicate repeated vomiting;

- tenderness in the right upper quadrant may indicate cholecystitis;

- right lower quadrant tenderness may indicate appendicitis;

- pain in the epigastrium may indicate a peptic ulcer of the stomach and/or duodenum;

- palpable mass in the abdominal cavity;

- perform auscultation - the absence of bowel sounds may indicate intestinal obstruction or complete obstruction.

General blood analysis

- Leukocytosis with band shift, anemia, accelerated ESR

Blood chemistry

- Creatinine, GFR, blood glucose, bilirubin, AST, ALT, a-amylase

General urine analysis

- Hematuria

Immunochemical analysis of feces for occult blood

Among women

- Pregnancy test

- age > 55 years

- unintentional weight loss

- progressive dysphagia

- constant vomiting

- gastrointestinal bleeding

- family history of gastrointestinal cancer

If you suspect

- for intestinal obstruction - radiography of the abdominal cavity (determining fluid levels);

- for appendicitis or acute cholecystitis (or as an additional examination for intestinal obstruction or kidney stones not detected by X-ray) - computed tomography of the abdominal cavity;

- for gallstones - ultrasound of the right upper quadrant;

- for intracranial pathology - computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain;

- for malignant neoplasms of the upper gastrointestinal tract - esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

- Types of nausea and vomiting in cancer patients

- Acute vomiting develops in the first 24 hours after chemotherapy and is characterized by high

- intensity, rarely accompanied by nausea.

- Delayed vomiting develops 2–5 days after the start of chemotherapy, less than

- more intense than acute, and, as a rule, is accompanied by constant nausea.

- Conditioned reflex vomiting is a classic conditioned reflex to chemotherapy and/or accompanying manipulations and the environment.

- Uncontrolled nausea and vomiting develops against the background of adequate antiemetic prophylaxis and requires additional correction.

- Refractory vomiting occurs in subsequent cycles of chemotherapy when antiemetic prophylaxis and/or reserve drugs in previous courses of treatment are ineffective.

Groups of drugs for the treatment of nausea and vomiting

5‑HT3‑receptor antagonists: ondansetron, granisetron, tropisetron, palonosetron

- In patients with congenital long-term QT syndrome, the use of first-generation 5-HT3 antagonists should be avoided, with the exception of palonosetron, which does not affect ECG parameters (QT interval).

- ECG monitoring is recommended in patients with signs of cardiac disorders, including heart failure, bradyarrhythmia.

- It is necessary to evaluate serum potassium and magnesium concentrations and provide symptomatic therapy in case of clinically significant abnormalities.

- Palonosetron is a drug of the latest generation, has the longest half-life (up to 40 hours), and is 100 times more potent at 5HT3 receptors than first-generation drugs.

Corticosteroids: dexamethasone

A certain positive preventive effect of hydrocorticosteroids (dexamethasone) during laparoscopic operations has been noted, allowing them to complement antiemetic therapy.

NK1 receptor antagonists: aprepitant, fosaprepitant

- They are moderate inhibitors and inducers of CYP3A4, which must be taken into account when using drugs metabolized by the same system simultaneously.

- Aprepitant increases the concentration of GCS.

- In patients receiving antivitamins K (warfarin), it is necessary to additionally monitor the INR level up to 2 times a week due to the effect of aprepitant / fosaprepitant on the activity of cytochromes.

Dopamine receptor blockers: phenothiazines (chlorpromazine or chlorpromazine, promethazine, methopemazine)

- antiemetic effect can block dopamine receptors in the trigger zone;

- can cause significant sedation (lethargy, drowsiness, lethargy, orthostatic hypotension), which limits their use in complicated cases and in outpatient settings.

Dopamine receptor blockers: benzamides (metoclopramide, itopride)

- metoclopramide is a specific blocker of dopamine (D2) and partially serotonin (5-HT3) receptors, having both central and peripheral antiemetic effects;

- used to prevent vomiting and regurgitation in patients at high risk of developing aspiration syndrome;

- increases the tone of the esophageal sphincter, increases gastric and intestinal motility, is effective for the prevention of vomiting that occurs during chemotherapy, as well as for the prevention of PONV, especially in those patients in whom narcotic analgesics (morphine, fentanyl) were used during anesthesia.

It is used in gastroenterological practice for gastrointestinal dysfunction, as well as in the treatment of dyspepsia, repeated vomiting, hiccups in cardiac patients and vomiting in pregnant women.

Dopamine receptor blockers: butyrophenones (droperidol, haloperidol)

- the antiemetic effect is due to the blockade of dopamine receptors and is often used in the practice of anesthesiologists for the prevention and treatment of nausea and vomiting in the postoperative period;

- their use is not recommended in outpatient settings (except in certain cases).

Antihistamines (diphenhydramine, hydroxycin, promethazine)

- act on the vomiting center and vestibular apparatus, they have been used to prevent motion sickness in transport;

- used in ENT practice to prevent vomiting after middle ear surgery;

- drugs in this group reduce the body’s response to histamine, reduce vascular permeability, have a sedative effect, inhibit nerve impulses in the autonomic ganglia, and have central anticholinergic and anti-inflammatory effects;

- used in the treatment of radiation sickness, sea and air sickness, vomiting during pregnancy, and Meniere's syndrome;

- have a calming and hypnotic effect.

Anticholinergics: Anticholinergics (atropine, metacin, scopolamine)

- prevent or weaken the interaction of acetylcholine with cholinergic receptors;

- Various types of cholinergic (muscarinic) receptors are found in the chemoreceptor trigger zone and vomiting center; most anticholinergics can form the basis for the prevention of nausea and vomiting;

- the use of atropine or metacin as premedication reduces the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting, even when using narcotic analgesics;

- the use of scopolamine effectively relieves motion sickness and reduces the frequency of vomiting after outpatient laparoscopy.

Dopamine receptor blockers: benzodiazepines (diazepam, lorazepam, alprozolam)

- a class of psychoactive substances with hypnotic, sedative, anxiolytic (reducing anxiety), muscle relaxant and anticonvulsant effects;

- the effect of benzodiazepines is associated with the effect on gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors;

- Benzodiazepines are part of a broad group of central nervous system depressants.

Antipsychotics: olanzapine

Its use at a dose of 10 mg may cause sedation, especially in elderly patients.

- Most often, nausea and vomiting are manifestations of diseases of organs not related to the gastrointestinal tract.

- The variety of causes of nausea and vomiting requires a systematic approach to diagnosis and treatment.

- It is important to review all medications that the patient receives, paying attention to their side effects.

- When examining a patient, it is necessary to take into account metabolic disorders caused by vomiting and its complications.

- If even after a thorough examination the cause of vomiting is not found, it makes sense to try antiemetics and prokinetic agents.

- For prolonged unexplained nausea and vomiting, tricyclic antidepressants may help.

Conclusion: the article discusses the main symptoms of damage to the gastrointestinal tract, as well as their causes, differential diagnosis and treatment.

List of used literature:

- WGO Global Guidelines Common Gl symptoms (long version) 19

- World Gastroenterology Organization 2013

- Drossman DA Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathopsysiology, clinical features and Rome IV 2016

Heartburn in pregnant women

Heartburn bothers 30-50% of pregnant women. In the absence of organic damage to the digestive tract, burning along the esophagus (functional heartburn) is caused by hormonally caused relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, increased pressure in the abdominal cavity and displacement of the stomach due to an increase in the size of the uterus. However, it is possible that the expectant mother develops a gastrointestinal disease or that an existing pathology has worsened.

Typically, heartburn first appears in the 20th week of pregnancy and torments the woman until childbirth. A common myth is that burning sensation in the esophagus is caused by hair growth on the fetal head. Expectant mothers should take care of proper nutrition and daily routine, and not believe in prejudices.

Pregnant women are not recommended to take antacid medications on their own. First, some medications can negatively affect the fetus. Secondly, it is extremely undesirable to trigger a serious illness. Malabsorption of nutrients can lead to fetal malnutrition and other abnormalities.

Important! Functional heartburn does not harm the unborn baby. The first step to getting rid of a burning sensation in the esophagus is maintaining proper nutrition.

Heartburn in children

In addition to problems with the digestive tract and dietary errors, heartburn in children can be caused by completely non-trivial reasons:

- neurological pathology,

- scoliosis,

- cystic fibrosis,

- ENT pathology,

- lung diseases.

In most children, heartburn is not as severe as in adults. However, unpleasant sensations cause discomfort to babies. Infants arch their backs, often burp, release gases and are capricious. At the same time, even with the slightest nutritional disorder in children, pain comes to the fore. Even slight bloating causes regularly recurring attacks of intestinal colic, and heartburn often leads to vomiting and refusal to eat. This can lead to insufficient weight gain, and uncontrollable vomiting quickly leads to dehydration.

Tips for parents for heartburn in children

- After feeding, the baby should be held upright for a while.

- If you have heartburn, first of all you should analyze your diet and diet, exclude all foods that cause heartburn (including limiting carbohydrates).

- Don't delay visiting the pediatrician. Against the background of prolonged heartburn and indigestion, anemia, apnea, and wheezing in the lungs may develop.

Important! It is necessary to exclude congenital anomalies of the digestive sphincter, intolerance to milk proteins and celiac disease.

Manifestations of flatulence

Flatulence

With flatulence, people usually complain of bloating (a feeling of fullness and heaviness in the abdomen), as well as aching pain in the abdominal area. The pain can also be acute (so-called “gas colic”). The pain usually goes away or decreases after the gas has passed.

There are two possible manifestations of flatulence.

At first, the passage of gases is difficult. In this case, there is an increase in the abdomen as a result of bloating of the intestines. The main complaint is discomfort or pain in the abdominal area.

With the second option, the gases escape, but this process itself causes concern. This happens often, violently and is not always controllable. This condition can significantly complicate our lives. There may be no pain; patient complaints are usually formulated as “rumbling” or “transfusion” in the abdomen. Flatulence may also be accompanied by:

- belching;

- bowel problems (constipation or diarrhea);

- nausea;

- bad breath;

- decreased appetite;

- shortness of breath (breathing disturbance due to flatulence is called dyspeptic asthma

. The swollen intestines compress the diaphragm, preventing a normal inhalation).

Sometimes, with flatulence, manifestations from the cardiovascular system are observed: a burning sensation in the heart area, headache, irregular heartbeat, etc.).

Heartburn due to coronavirus

With COVID-19, painful gastrointestinal symptoms, including heartburn, are caused by several factors.

- The coronavirus enters the gastrointestinal tract and provokes functional changes.

- Patients experience significant stress during their illness.

- With COVID-19, chronic diseases often worsen, and in our country up to 85% have problems with the gastrointestinal tract.

- Due to the frequent gastrointestinal symptoms, the “delta” strain of coronavirus has already been called “stomach covid.”

Important! Heartburn with coronavirus, especially in combination with severe weakness, increasing shortness of breath and worsening cough, may indicate a severe course of the disease.

Recent studies have shown that over the next year, patients who have recovered from COVID-19 have a significantly increased risk of developing diabetes mellitus, autoimmune gastrointestinal diseases and psychosomatic disorders, including gastric ulcers. Therefore, if heartburn occurs, patients recovered from coronavirus should visit a gastroenterologist.

Important! Information has appeared in the press that the heartburn drug Famotidine improves the well-being of patients with coronavirus. However, only 10 people participated in the study, and therefore it is premature to talk about the effectiveness of this drug and its safety against COVID-19. We strongly advise against taking Famotidine on your own without a doctor’s prescription.

Diagnosis of heartburn

Recommended Laboratory Tests

- General blood analysis.

- Biochemistry and liver tests.

- Test for antibodies to Helicobacter pylori.

- Coprogram.

Instrumental studies

- Urease breath test for Helicobacter.

- FGDS with the possibility of taking a biopsy (to exclude cancer).

- Ultrasound, X-ray with contrast agent and CT.

- Esophageal pH monitoring, esophageal manometry.

If necessary, the patient is referred to an endocrinologist, pulmonologist, cardiologist and other highly specialized specialists.

Treatment of heartburn

- Correction of the diet - do not overeat (especially at night), the last meal is 2.5-3 hours before bedtime, the interval between meals is 4-5 hours, the portions are small.

- Eliminate from the diet all foods that cause heartburn - fatty, fried, spicy, citrus fruits, coffee, alcohol, fresh vegetables and fruits, avoid chewing gum (increases the secretion of gastric juice).

- Allowed dishes: soups, boiled lean meat and fish, porridge (oatmeal, rice, buckwheat), yoghurt, milk (low-fat sour cream, ice cream, cottage cheese in limited quantities), baked apples, boiled vegetables.

- Sleep hygiene is to sleep on your left side with the head of the bed raised. Elevating your upper body by 15% will reduce your risk of heartburn by 50%.

- Symptomatic therapy - before meals, take drugs that neutralize acid (antacids, alginates). It should be remembered that some of them (for example, Almagel) are not recommended for children, and the duration of their use is limited.

- Correction of high gastric acidity and treatment of GERD - proton pump inhibitors.

- Improving the motor function of the gastrointestinal tract - prokinetics (required as prescribed by a doctor; they have serious side effects).

- Antibacterial therapy - when Helicobacter is detected, two or three antibiotics are combined.

- Means for improving digestion - enzymatic preparations.

- General strengthening therapy - vitamins, probiotics.

- Surgical treatment - for severe GERD, gastric ulcers that are refractory to drug therapy.

Drugs for the treatment of heartburn and the underlying disease are selected on an individual basis. Not a single, even the most effective drug will help get rid of heartburn without following a diet.

Features of treatment of Barrett's esophagus with nocturnal hypersecretion of gastric juice

Barrett's esophagus is a critical condition because changes in the esophageal mucosa can progress to adenocarcinoma. Effective control of hypersecretion of gastric juice can stop the progression of the disease and prevent malignant neoplasms. Therefore, effective 24-hour gastric acid suppression is critical for this group of patients. Unfortunately, in patients with scleroderma and esophagitis, it is possible to control acidity only in 50% of cases.

Removing acid from the esophagus is a two-step process involving volume reduction and acid neutralization. During this process, most of the acid is removed from the esophagus during primary and secondary peristalsis, the influence of bicarbonates secreted by the salivary and submucosal glands of the esophagus.

Normally, acid clearance decreases during sleep. At night, swallowing practically stops, and therefore there is no stimulation of primary peristalsis. Due to the low food content in the stomach, secondary peristalsis is practically not stimulated.

Based on experimental studies, it is assumed that secondary peristalsis in patients with GERD and the elderly is not affected by the same conditions as in healthy people. Acid clearance of the esophagus in patients at night is worse than during the day, not only because of the supine position, but also because of the lack of swallowing and the reduced content of bicarbonate in saliva, which neutralizes acid.

Nocturnal acid secretion can be especially harmful due to prolonged contact of the acid with the mucous membrane. Nocturnal hypersecretion of gastric acid is common in patients with severe reflux effects such as erosive esophagitis and Barrett's esophagus.

Barrett's esophagus

The nocturnal symptoms of GERD are influenced not only by a decrease in peristaltic activity, but also by a violation of the lower pressure in the esophagus and increased sensitivity of the esophageal mucosa.

When monitoring pH daily in patients with symptoms of nocturnal reflux, the most common cause of problems was moderate acidity (pH 4-7), pepsin and bile in the reflux.

Preventing heartburn

- Eliminate heavy lifting.

- Sleep at least 7 hours.

- Do not bend over or go to bed for 1.5-2 hours after eating.

- Avoid corsets, bandages and tight trousers.

- Quit smoking, don't abuse alcohol.

- Get rid of extra pounds.

- Don't skip preventive examinations.

- When the first complaints appear, consult a doctor.

- If you have gastrointestinal diseases, visit a gastroenterologist 2 times a year.

- Control of emotional state, help from a psychologist.

Taking into account the increasing number of cancers, which at the initial stage manifest themselves with minimal symptoms, recurrent or constant heartburn cannot be ignored. Contact the First Family Clinic of St. Petersburg. You will undergo the necessary studies, and gastroenterologists will prescribe effective treatment.

Why can sweets cause heartburn?

An unpleasant burning sensation behind the sternum has a direct connection with nutrition. An excess of simple carbohydrates in the diet can increase acid production and also provoke increased gas formation1. Both parameters increase the risk of food reflux from the stomach into the esophagus, which can cause heartburn.

Carbohydrate foods that may cause burning include:

- chocolate;

- cakes, butter cookies;

- sweet carbonated drinks;

- sweet coffee and tea;

- any baked goods;

- fruit juices with sugar;

- sweets2,3.

Not every person gets heartburn from sweets. The risk of developing a symptom increases if there are additional factors:

- binge eating;

- eating fried, fatty foods;

- smoking;

- alcohol consumption;

- overweight;

- pregnancy;

- wearing tight belts;

- excessive physical activity after eating, especially bending;

- horizontal position after eating3.

The occurrence of heartburn after eating sweets more than once a week for several months may indicate the development of gastroesophageal reflux disease2. Main symptoms: heartburn and sour belching3. The disease occurs due to persistent weakening of the muscular sphincter between the stomach and esophagus2.