Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics

Pharmacodynamics

Summarizes the thymoleptic effect with a moderate effect on the nervous system, while the stimulating effect on patients with depression of the anergic and apathetic type is combined with a sedative effect on people in an agitated state.

Selectively, short-term and reversibly inhibits type A MAO ( monoamine oxidase ); to a large extent inhibits the deamination of norepinephrine and serotonin , and to a small extent – tyramine . The reverse addition of monoamines is also partially inhibited. Stimulates the mechanisms of synaptic transmission of excitation in nerve fibers.

Suppresses the depressive effect of reserpine , activates the effects of dioxyphenylalanine (L-dopa - a precursor of norepinephrine ), stimulates adrenergic structures and serotonergic structures, the effects of 5-hydroxytryptophan (a chemical precursor of serotonin ).

Does not have an anticholinergic effect. It has a nootropic effect and enhances cognitive functions.

Pharmacokinetics

Almost completely absorbed from the digestive tract. After a single oral dose, the highest concentration of the active component in the blood plasma is recorded after 3-7 hours. The equilibrium concentration is fixed two weeks after administration.

Removal from the blood occurs in three stages. Bioavailability is about 20-30%, almost all of the drug is metabolized in the liver. It has a high affinity for plasma proteins (up to 95%) and a long half-life - up to eight days. Distributed in the spinal cord, hypothalamus, cerebral cortex, as well as in the kidneys, liver, lungs, and spleen. About half of the metabolites are excreted by the kidneys, another 25-45% are excreted in the bile, and a small amount is excreted in the urine in its original form. Does not accumulate in the body, does not cause withdrawal or addiction syndrome.

Pyrazidol in the treatment of depression. Positions are saved

A temporary feeling of depressed mood is well known to almost every person, especially in connection with the experience of failures, troubles, and grief. However, depression is defined as a pathological condition if it meets the diagnostic criteria specified in modern classifications of mental illnesses, in particular in ICD-10, familiarity with which is necessary not only for psychiatrists, but also useful for doctors of other specialties. Accurate adherence to these diagnostic recommendations allows you to avoid both over- and underdiagnosis of depression. Main signs of depression

characterized by feelings of sadness, depressed mood, loss of interest in any activity and decreased energy.

Other symptoms include loss of self-confidence, low self-esteem, unreasonable feelings of guilt, thoughts of not wanting to live, decreased ability to concentrate, sleep and appetite problems. In this case, a number of somatic symptoms may be present that accompany depressed mood (weight loss, tendency to constipation, weakened libido, etc.). The characteristics of depressive disorder are supplemented by determining the degree of its severity (mild, moderate, severe), and the persistence of depressive symptoms for a period of at least two weeks. Depression can be episodic, occurring

as a single or recurring condition, or become

chronic

in approximately 20% of cases, especially when appropriate treatment is not provided [1].

The nosological affiliation of depression is different. Depressive disorders are observed in endogenous affective diseases and in schizophrenia, mainly with a paroxysmal course, as well as within the framework of low-progressive schizophrenia. Depression makes up the majority of stress-related disorders

and occurs with decompensation of personality pathology.

It is also possible to develop depression with organic brain damage. A study of the epidemiology of depression [11] showed that the least diagnostic difficulties are caused by severe depression, the treatment of which is carried out, as a rule, in a specialized psychiatric hospital. These are the so-called hospital depression

, they make up less than 1%.

The second group is community-acquired depression

, for which specialized care is provided on an outpatient basis; there are about 5% of them.

The third group includes depression, designated as non-institutional

.

Patients in these cases most often turn to a general practitioner with various complaints, since they cannot figure out whether they are somatically or mentally ill. They go to a psychiatrist only on the advice of internists and prefer to be treated by a specialist only in a general medical institution. The least certain diagnosis is of erased depressive disorders or symptoms detected during medical examinations (dispensary and medical examinations, epidemiological studies). The idea of the prevalence of depression has changed significantly over the past decades, showing an increase several times. The incidence of depression, according to WHO, is 3%. Depression is more common among women. The increase in the incidence of depression is explained by social stress factors, increased life expectancy, evolutionary and therapeutic pathomorphosis and other reasons, among which changes in the organization and forms of psychiatric care are most likely to interpret this phenomenon. First of all, this concerns the expansion and optimization of the work of outpatient psychiatric institutions and services. The introduction of consultative psychiatric care into inpatient and outpatient settings of general medical practice has also led to an increase in the detection of depressive disorders, especially their atypical forms associated with somatic disorders. Wide coverage of these forms of depressive disorders not only in the psychiatric and medical literature, but also in the media has contributed to the acquisition of new knowledge about depression by doctors of various specialties, as well as awareness of patients and the population as a whole. This has led to the fact that in some cases, patients with these disorders began to independently seek help, assuming that their somatic complaints and disorders, not confirmed by the results of examinations, were explained by special manifestations of depression. As stated in the WHO World Health Report 2001 [1], depression poses a huge burden on society and on the patient, significantly impairing quality of life and often leading to disability. At a young age, the burden of loss due to disability due to depressive illness is 8.6% of the number of years of life lost due to disability. The burden of depression on society is expected to increase in the coming century.

According to experts, depression will take second place among the leading factors determining the number of years of life lost due to disability, and will be second only to coronary heart disease in this characteristic.

The relapse rate for those recovering from depression after a first episode is approximately 35% within the first two years and approximately 60% within 12 years. This figure increases in the group of patients over 45 years of age. It is well known that the most tragic outcome of depressive disorder is suicide. Approximately 15–20% of patients suffering from depression commit suicide. Suicide is one of the outcomes of depressive conditions, the prevention of which is most achievable. Depression can affect people at different ages in life, but most often occurs in adulthood. However, more and more evidence indicates the frequency of depression in adolescence and young adulthood.

At this age, depression is often masked not only by somatic symptoms, but also by various other forms of disorders, including manifestations of delinquent behavior.

In younger children, in addition to behavioral disorders, tearfulness, irritability, and depression are expressed in somatic complaints, autonomic symptoms, asthenic disorders with loss of play activity, childish liveliness, and unexplained fluctuations in academic performance. Difficulties in diagnosing depression in children are largely due to problems in formulating complaints and the inability to self-report. In many cases, the observation and attention of parents and teachers is crucial, as well as the attitude of alertness of the pediatrician regarding the possibility of childhood depressive disorder in explaining the reasons for his ailment or changes in behavior, which, in turn, dictates the need for timely consultation with a specialist. Significant features distinguish mood pathology during the development of depression in adolescence and young adulthood. Actually, hypothymia or a depressed mood is not manifested by melancholy, but mainly by a feeling of joylessness of existence, the experience of indifference with a loss of strength, loss of interests, impaired concentration, difficulties in perceiving educational material and complaints about memory deterioration, dissatisfaction with oneself with a painful experience of one’s physical and intellectual imperfection. In adulthood, the standard manifestations of depression were usually considered to be clinical signs of inhibited melancholy depression with depressive ideas of self-abasement and guilt.

Patients with such manifestations of depression are found mainly in hospitals (however, less and less often).

Doctors more often have to deal with depressive disorders of lesser depth, but at the same time, in the clinical picture of depression, manifestations or experiences of anxious anxiety, the degree of severity of which can vary within different limits, become almost obligate or at least very frequent. As a rule, anxiety is accompanied by various kinds of apprehension, fear, and most often this concerns the topic of health with hypochondriacal concern. Vital experiences of melancholy and mental pain are replaced by a variety of bodily sensations, often of an algic nature, while maintaining a predominantly retrosternal localization. The painful experience of anxiety takes on a pronounced physical character and is described by patients as painful internal tension, painful excitement, and internal trembling. The increase in this kind of atypical depression is often associated with drug pathomorphosis, when the widespread use of psychotropic drugs caused a weakening of the severity of melancholic symptoms themselves and led to the transition of many mental disorders to a circular level with a more distinct phase-periodic course. At the same time, a direct increase in the prevalence of erased, “dull” forms of depression,

often characterized by persistence of symptoms and resistance to therapy, is recognized.

A well-known sign of the use of overly figurative, sometimes bizarre expressions in conveying one’s feelings and condition in general allows one to differentiate pathological sensations from pain syndromes in somatic diseases, in particular, cardialgia from angina pain in coronary heart disease. Naturally, recognizing the possibility of somatization of depressive symptoms should not lead to overdiagnosis of depression and ignoring the real somatic disease or the need to exclude it [13]. At the same time, depressive mood disorders influence the manifestations of somatic illness and limit the possibilities of therapy due to the low compliance of depressed patients. Meanwhile, it has long been noticed and shown in special studies that depression reduces life expectancy in cases of coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction and other diseases.

An increase in the detection of non-psychotic depression is particularly evident among elderly and senile patients, with mild and moderate depression occurring almost 10 times more often than severe forms of depression requiring inpatient treatment in geriatric departments of psychiatric hospitals.

Late age is considered to be the peak age in relation to the incidence of depressive disorders in patients of general somatic practice. It is known that older people especially rarely use psychiatric help, not only because of their reluctance to turn to such specialists. This often happens due to the habitual views of some medical workers, who attribute mental symptoms either to manifestations of irreversible age-related changes or to somatic ailments of old age. Difficulties in recognizing depression in later life are also due to the fact that older depressed patients are less inclined to consider their condition painful, preferring to see it as a psychological problem, using various life circumstances to explain it. Almost all depressive symptoms in late-life patients show distinct age-related characteristics [4,12]. Depression in late life is primarily anxiety depression.

Characteristic is a combination of bodily sensations of anxiety and its ideational manifestations in the form of an anxious influx of thoughts with fears of various contents.

Daily mood swings in late-life depression are characterized not only by worsening well-being in the morning, but also by increased anxiety in the evening. The phenomenon of somatization of depression, which is also observed in late age, is the main reason for the difficulties in identifying and diagnosing these disorders, while, according to WHO data [1], half of elderly depressed patients in general somatic practice show signs of masked depression. The multifactorial phenomenon, well known in gerontopsychiatry, lies in the ambiguous interpretation of the genesis of depressive disorders in late life. The nosological spectrum of depressive conditions includes not only endogenous depressions that first developed or recur at a later age, but also a wide group of depressive reactions of maladaptation, dysthymia, and psychogenic-somatogenic depression (nosogenies). Depressions of organic origin, including post-stroke, are becoming increasingly relevant, the occurrence of which is explained not only by the individual’s reaction to the severity of suffering, but is increasingly associated with damage to the cerebral hemispheres. Intensive development of ideas about the initial stages of dementia in Alzheimer's disease has revealed the frequency of depressive symptoms and conditions at the onset of this disease. Treatment with antidepressants is the main type of therapeutic intervention

, regardless of the nosological affiliation of depression, which includes the entire spectrum of mental illnesses.

The choice of antidepressant is determined primarily by the psychopathological picture of depressive disorder. The principle of prescribing certain antidepressants depending on the type of depression and the predominant severity of its main symptoms, confirmed by clinical experience, is still widespread. Currently, the concept of predicting the effectiveness of antidepressive therapy is gaining recognition [14], based on an analysis of the ratio of symptom complexes of positive and negative affectivity, that is, the presence in depression of the phenomena of melancholy and anxiety, on the one hand, and the phenomena of alienation, apathy, anhedonia, mental anesthesia, with another. Despite the emergence of a large number of different new antidepressants, which are certainly safe and quite effective, well-known drugs for the treatment of depression do not lose their importance and, moreover, they are again arousing the active interest of researchers and practitioners. Such drugs include the domestic antidepressant Pyrazidol

, jointly developed more than 30 years ago by pharmacologists from VNIHFI and psychiatrists from the Research Institute of Psychiatry of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation.

For almost 20 years, the drug was successfully used to treat depression until, due to the economic situation, its production was discontinued, and then resumed after a ten-year break in 2002. The absence of Pyrazidol on the pharmaceutical market was very noticeable for doctors and patients, since this antidepressant occupied a special place in terms of the characteristics of its clinical action, tolerability and the possibility of prescription for certain types of somatic pathology (glaucoma, prostate adenoma), which are a contraindication to many antidepressants. Pyrazidol (pirlindol) is one of the first representatives of selective reversible monoamine oxidase inhibitors. The activity of this enzyme is restored within several hours, and therefore the drug does not cause tyramine reactions. According to its chemical structure, it belongs to the group of four-cyclic antidepressants. Pyrazidol exhibits an original mechanism of action, having the ability to simultaneously inhibit the activity of MAO and block the pathways of metabolic destruction of monoamines, selectively deaminating serotonin and adrenaline. By thus influencing the currently known neurochemical mechanisms of depression, the drug realizes its antidepressant properties. Pyrazidol is rapidly absorbed, absorption is slowed down by food intake. The bioavailability of the drug is 20–30%. More than 95% of the drug binds to blood plasma proteins. The main route of metabolism is renal. The pharmacokinetics of Pyrazidol does not show a linear dose dependence. The half-life of the drug ranges from 1.7 to 3.0 hours. The therapeutic effect occurs after 3–6 weeks. When carrying out antidepressant therapy, Pyrazidol is prescribed orally in tablets containing 25 or 50 mg. Initial daily doses are 50–100 mg, the dose is increased gradually under the control of clinical effect and tolerability up to 150–300 mg per day. For the treatment of mild and moderate depression, a daily dose of 100–200 mg is usually sufficient; for more severe depressive conditions, the dose of the drug can be increased to 250–300 mg per day. The maximum daily dose is 400 mg. A judgment about the effectiveness of treatment with Pyrazidol can be made after three to four weeks of taking the drug. If a positive result is achieved, treatment should be continued for 4–6 months as maintenance therapy to prevent relapses. Discontinuation of the drug should be carried out after a gradual reduction of the dose over a month under the control of the mental state in order to avoid the development of deterioration or withdrawal syndrome with vegetative symptoms (nausea, anorexia, headache, dizziness, chills). Toxicological studies have shown the absence of potentially dangerous toxic effects of Pyrazidol,

even with long-term administration of doses exceeding therapeutic ones.

No clinically significant mutagenic, carcinogenic and clastogenic (induction of chromosomal aberrations) properties were detected. Pyrazidol is part of an intermediate group of antidepressants with a wider, polyvalent or balanced spectrum of action. The thymoanaleptic effect of Pyrazidol is quite pronounced, but inferior to anafranil; In terms of overall (global) effectiveness, the drug is considered a second-rank antidepressant [7]. The severity of the stimulating properties of Pirazidol is less than that of imipramine and clomipramine, but more than that of fluoxetine, liidomil and amitriptyline. The anxiolytic effect of the pirazidol is superior in fluoxetine. By the power of antiphobic action, the drug is inferior to clomipramine, Siox, but surpasses amitriptylin, Liiomil. Sedative and hypnotic properties are less pronounced than that of tricyclic antidepressants, but more noticeable than fluoxine, fluitsamine. The main feature of the clinical effect of Pirazidol

is that the drug as an antidepressant

is characterized by tropisms of both alarming and inhibited depression

.

The clinical aspects of the use of pirazidol for the treatment of depression in the first 20 years after its development were diversely studied during special studies in the country's leading psychiatric centers. The object of the study was stationary patients mainly with endogenous depression. Quickly, the positive experience of using Pirazidol as an antidepressant also spread to outpatient care of patients with shallow forms of depressive disorders in different age groups of patients. The circle of indications for the use of the drug has expanded significantly. In addition to endogenous depressions, Pirazidol found his effectiveness with depression of other genesis, in particular, with various psychogenic -conditioned depressive states, depression in the framework of organic diseases, as well as depressive disorders in common -scale practice. The results of scientific studies conducted by comparing the antidepressant properties of pyrazodol with the clinical effects of other well -known antidepressants showed a significant originality of this drug. In these works [6.9.10], the undoubted effectiveness of Pirazidol was affirmed with respect to depressive symptoms

, a fairly rapid onset of the therapeutic effect and high safety of use.

A wide spectrum of the therapeutic effect of the drug on the manifestations of depression was unanimously recognized, in connection with which Pirazidol was called the drug "universal", "balanced" action. A clear effect of Pirazidol was found on various components of the depressive syndrome, while the thymoanaleptic effect and activating simultaneously with a distinct anxiolytic effect was revealed. The severity of these individual manifestations of the antidepressant activity of the drug was evaluated by the authors of the first studies in the same way. Pirazidol did not exceed the antidepressants of the first generation in power of thymoanaleptic influence and even inferior to them in this, but at the same time found certain advantages due to the fact that he did not cause exacerbations of psychotic symptoms, excitement and inversion of affect. The activating effect of Pirazidol was characterized by the softness of the effect on the symptoms of inhibitance and adynamia, did not lead to increased anxiety, agitation and tension. The most interesting feature of the antidepressant action of Pirazidol was in a combination of an activating and at the same time anti -alert effect in the absence of hyperrandation, drowsiness and increased inhibition, which, as is known, are characteristic of tricyclic antidepressants. The noted lack of sharp dissociation between the activating and anxiolytic effects of Pirazidol determined the harmonious therapeutic effect on the symptoms of depression. At the very beginning of the clinical study of the drug, its dose -dependent effect was noticed. The use of pirazidol in small and medium doses (75–125 mg) revealed its activating effect more clearly, with an increase in the dose of the drug (up to 200 mg and above), the anti -conveying component of the antidepressant action of Pirazidol was more obvious. If necessary, combined therapy, along with Pirazidol, was prescribed antipsychotics, tranquilizers and anticonvulsants - normic. The forced absence of Pirazidol for many years in the arsenal of the treatment of depression was very noticeable. Despite the emergence of new generations effective and safe in the use of antidepressants of adequate replacement for this drug, practically did not appear. The return of Pirazidol to clinical practice was confirmed by its demand and the ability to compete with new antidepressants due to the practical lack of holinolytic side effects, relatively high efficiency and accessibility of acquisition. From the point of view of the clinician who faces the choice of an antidepressant in a specific clinical situation, it is important that Pirazidol has its own therapeutic “niche”

, the boundaries of which have expanded significantly due to the fact that depression of light and moderate severity with an atypical picture and the prevalence of anxious- hypochondriacal disorders in their structure.

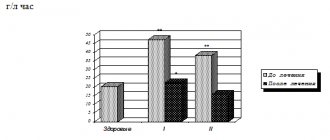

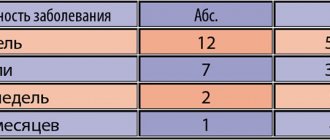

Both psychiatrists and interners are engaged in the treatment of these widespread disorders. The appointment of Pirazidol is completely justified and brings the greatest effect with blurry, insufficiently clearly designed or polymorphic depressive syndromes, as well as with unstable conditions with fluctuations in depth and variability of the structural components of depression [8]. In the currently conducted studies, the psychopharmacological activity of Pirazidol is evaluated from the standpoint of the concept of positive and negative affectiveness. It is shown that in the treatment of depressions of the non -cosichotic level [2], Pirazidol reveals reliable effectiveness in depression with a predominance of positive affectiveness. Among the responders were patients with depression, in the manifestations of which the leading were vital, alarming and senesto -hypochondriacal symptoms. Apatoadynamic and depersonalization depression, that is, depression with negative affectiveness, enhaningly worse responded to Pirazidol treatment. The total effectiveness of therapy was 73%. It is noted that the drug reveals equal strength to the stimulating and sedative effect, and the reverse development of symptoms of anxiety is ahead of the positive dynamics of the proper hypotimia. In addition to using the drug in general psychiatry, it is shown that Pirazidol can be successfully used to stop affective disorders

, which accompany the most diverse pathology of internal organs.

The vegetostabilizing effect of the drug allows you to use it in the treatment of vegetative and somatized depression. It is recommended that Pirazidol are prescribed for the treatment of depression in patients with chronic pain, in particular, lumbosacral localization [15]. Good tolerance of the drug has been proved in cases of combination of mental and somatic pathology and the possibility of combination with basic therapy. As shown in the recently conducted study of the therapeutic effect of the pyrazodol in the treatment of depressive disorders in patients with coronary heart disease (3), the drug does not have “cardiotoxicity”, does not affect the level of blood pressure, heart rate, does not cause orthostatic hypotension and detects protective properties in conditions of tissue hypoxia due circulatory disorders. It is noted that Pirazidol does not enter into a clinically significant interaction with the basic cardiotropic agents used in the treatment of coronary heart disease. The detection of neuroprotective, antioxidant properties of pirazidol in the conditions of hypoxia, including circulatory, opens up the prospects for studying the use of this antidepressant as a corrector of cognitive dysfunctions [8]. It seems completely justified by the appointment of Pirazidol as an antidepressant of the first choice for the treatment of depressive conditions

, which are increasingly revealed at the initial stages of late age dementia.

It is also essential that the drug has practically no cholinolithic effects that are characteristic of many antidepressants and extremely undesirable due to increased cognitive disorders in the conditions of existing acetylcholine deficiency in elderly patients with dementia. Pyrazidol treatment, as a rule, is not accompanied by the development of clinically significant undesirable effects or they are very rare in comparison with the tricyclic antidepressants and irreversible MAO inhibitors found when using tricyclic antidepressants. Typically, orthostatic hypotension and heart rhythm disturbances are not observed. The deviations in the genital area characteristic of some antidepressants are not noted. Holinolytic effects such as drowsiness and sedation are found very rarely. At the same time, the appointment of Pirazidol usually does not lead to the strengthening or development of insomnia and agitation, rarely causes gastrointestinal disorders. Pirazidol is incompatible with other MAO inhibitors, including with drugs that have such activity (Furazolidone, Procarbazin, Selegilin). In relation to the last specified drug, this should be particularly borne in mind, since Selegilin is widely prescribed in neurological practice for the treatment of diseases in which depressive disorders are frequent (Parkinson's disease, soft dementia of vascular and atrophic genesis). With the joint use of pyrazidol with adrenromimetics and products containing thyramine, an increase in the pressing effect is possible. It is undesirable to take pyrazidol and thyroid hormones at the same time: also due to the risk of arterial hypertension. It is unfavorable for the drug interaction of Pirazidol and Tsimetidine, since the metabolism of the pirazidol slows down, its main effect is intensified in this regard and the risk of side effects increases. Pirazidol has the ability to enhance the action of analgesics. You can not combine Pirazidol with dextrometerfan due to the possibility of toxic reactions by the central nervous system [5]. The combined use of pirazidol simultaneously with tricyclic antidepressants and selective inhibitors of the reverse capture of serotonin is not recommended, since symptoms of serotonergic hyperactivity (hyperthermia, confusion, hyperreflexia, myoclonus) are possible. But their appointment is permissible immediately after the cancellation of Pirazidol. Of particular interest is the combination of pirazidol with nootropes and tranquilizers. It was established that piracetam enhances the action of pirazidol, as well as other antidepressants. This can matter in the tactics of treatment of depression aimed at overcoming therapeutic resistance or reducing the therapeutic dose of the drug with poor tolerance. With a combination of pyrazidol with diazepam, the sedative effect of diazepam is weakened without a decrease in its anxiolytic effect, while the anticonvulsants of diazepam are even intensified. This interaction of pyrazidol with diazepam can be used to reduce the side effects of benzodiazepines. Thus, the successful past experience in applying the domestic antidepressant Pirazidol is reproduced in modern studies, which confirms the need for its use in the therapy of a wide range of depression in general psychiatry and somatic medicine. Literature:

1. WHO report on the state of healthcare in the world 2001. Mental health: new understanding, new hope. “The whole world”, 2001, p. 37–84. 2. Dubnitskaya E.B., Goldel B.A. Therapy of depressions of a non -tochihotic level (experience in the use of Pirazidol: Efficiency and Safety). J. Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy, 2003, No. 3, p.106–108. 3. Ivanov S.V., Syrkin A.L., Drobizhev M.Yu. et al. Pirazidol in the treatment of depression in patients with coronary heart disease. Ibid., 2004, vol. 5, No. 4, p. 171–173. 4. Kontseva V.A., Medvedev A.V., Yakovleva O.B. Depression and aging. In the book: Depression and comorbid disorders. M., 1997, p. 114–122. 5. Malin D.I. Medicinal interactions of psychotropic drugs (part 11). J. Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy, 2001, No. 1, p. 20–24. 6. Morozov G.V., Rudenko G.M. Features of the clinical effects of Pirazidol in comparison with other antidepressants. In the book: antidepressants and nootropics. Leningrad, 1982, p. 29 -Z7. 7. Mosolov S.N. Fundamentals of psychopharmacology. M., 1996, p.1–288. 8. Mosolov S.N., Kostyukova E.G. The use of pirazidol in the treatment of depression (information letter, part 1). J. Psychiatry and Psychopharmacotherapy, 2003, T.5, No. 6, p. 245–246. 9. Muzychenko A.P. To the question of the "balancing" action of antidepressants of Pirazidol and Luidomil. In the book: antidepressants and nootropics. Leningrad, 1982, p. 37–42. 10. Panteleeva G.P., Belyaev B.S., Borisova K.E. et al. On the thymoleptic activity of domestic drugs Pirazidol and Incrac. Ibid., S. 42–48. 11. Rothstein V.G., Bogdan M.N., Dolgov S.A. Epidemiology of depression. In the book: Depression and comorbid disorders. M., 1997, p. 138–164. 12. Siryachenko T.M., Mikhailova N.M. Soft depression of a late age. In the book: affective and schizo -appetizing psychoses. M., 2001, p. 219–225. 13. Smulevich A.B. Depression in general somatic practice. M., 2000, p.1–160. 14. Smulevich A.B., Glushkov R.G., Andreeva N.I. Pirazidol in clinical practice. Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy, 2003, No. 2, p. 64–65. 15. Chakhava K.O. Pyrazidol therapy of chronic pain disorders of lumbosacral localization. Russian Medical Journal, 2003, Volume 11, No. 25 (197), p.1415–1418.

Instructions for use of Pyrazidol (Method and dosage)

Instructions for use of Pyrazidol prescribe taking the drug orally.

Pyrazidol is prescribed at an initial dose of 50-75 mg per day in 2 divided doses. It is gradually increased by 25-50 mg until a dose of 150-300 mg per day is reached. The maximum daily dose is 400 mg. Usually the dose is divided into 2-3 doses.

After fixing the therapeutic effect, the drug is continued to be taken in an individually selected dosage for up to one month. Then the dose is slowly reduced.

Publications in the media

(Pirlindolum) INN

Synonyms. Pyrazidol.

Composition and release form. Pyrazidol tablets of 0.025 and 0.05 g.

Indications. Affective insanity; schizophrenia with affective disorders and involutional psychosis occurring with depression; depression with psychomotor retardation; depression, accompanied by anxiety-depressive and anxiety-delusional components, anesthetic, hypochondriacal and neurosis-like symptoms; abstinence period in patients with alcoholism, reduction of depressive and anxiety-depressive states; complex therapy of senile dementia.

Pharmachologic effect. Pyrazidol is an original domestic antidepressant that combines a thymoleptic effect with a regulatory effect on the central nervous system, which manifests itself, depending on the dose, in an activating effect in patients with apathetic, anergic depression and in a sedative effect in patients with agitated conditions. The antidepressant effect of pyrazidol is primarily associated with its ability to reversibly and selectively inhibit MAO type A, which allows it to be considered as a second-generation MAO inhibitor antidepressant. Another important point in the mechanism of action of pyrazidol is the blocking of the reuptake of monoamines, which leads to their accumulation and to significant activation of the processes of synoptic transmission of nervous excitation in the central nervous system and, consequently, to a reduction or elimination of depression. It clearly inhibits the process of deamination of serotonin to a lesser extent of norepinephrine and has little effect on the deamination of tyramine, creating the prerequisites for the development of “raw syndrome”, which is manifested by a sharp increase in blood pressure when taking foods rich in tyramine. Pharmacokinetics. The drug is well absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract into the blood. Metabolized in the liver.

Side effects. Dry mouth, sweating, hand tremors, tachycardia, nausea, dizziness.

Contraindications. Acute inflammatory liver diseases; diseases of the hematopoietic system.

Adverse reactions when interacting with other drugs. Pyrazidol should not be prescribed simultaneously with antidepressants - MAO inhibitors, since their combined use increases the risk of developing hypertension, up to a hypertensive crisis, and cardiac dysfunction. After using MAO inhibitors, pyrazidol can be prescribed after 2 weeks. In connection with the antimonoamine oxidase activity of the drug, the possibility of an increased reaction to adrenaline and other sympathomimetic amines should be taken into account if they are administered to a patient while taking pyrazidol.

Information for the patient. Treatment with pyrazidol begins with a dose of 0.05-0.075 g per day in 2 divided doses, gradually increasing the dose. The drug is taken 30-40 minutes before meals; if signs of irritation of the gastric mucosa appear, take after meals. To avoid the development of “cheese syndrome” during treatment with pirlindol, it is necessary to exclude from the diet foods containing tyramine and other vasoconstrictor monoamines, namely: cheese, cream, coffee, beer, wine, smoked meats, chocolate, smoked and pickled herring. These products contain tyramine, a biogenic amine that causes a vasoconstrictor effect, and when pirlindole is administered, a sharp increase in blood pressure may occur, up to a hypertensive crisis. To avoid disruption of night sleep, it is not recommended to take pirlindole in the evening.

Interaction

When co-prescribed or used with Pyrazidol immediately after or during treatment with drugs that block MAO (for example, procarbazine, moclobemide, selegiline, furazolidone ), severe complications such as serotonin syndrome .

Pyrazidol can increase the sensitivity of patients to epinephrine and a number of other amine sympathomimetics - this should be taken into account if their combined use is necessary.

Analogs

Level 4 ATC code matches:

Pipofezin

Bethol

Incazan

Melitor

Azafen

Miaser

Velafax

Mirtazonal

Venlaxor

Remeron

Venlafaxine

Lerivon

Mirtazapine

Cymbalta

Velaxin

Coaxil

Deprim

Gelarium Hypericum

Negrustin

Trittico

Cymbalta, Alventa, Velaxin, Wellbutrin SR, Venlaxor, Venlift, Gelarium Hypericum, Melitor, Deprivit, Mirzatel, Mirtel, Trittico and others.