Indications for use

NSAIDs are used for inflammatory diseases of connective tissue, which are accompanied by damage to joints, cartilage, tendons, ligaments - arthritis, arthrosis, osteochondrosis, spondyloarthritis, tendovaginitis, bursitis.

NSAIDs are used for conditions that are accompanied by mild or moderate pain: headache, dental, menstrual, muscle, joint, as well as pain due to muscle injuries, joints, ligament damage, neuralgia.

Together with narcotic analgesics, NSAIDs are used for multiple injuries and pain after surgery.

In combination with antispasmodics, analgesics-antipyretics are used for pain associated with spasm of smooth muscles - hepatic, renal, intestinal colic.

In addition, certain NSAIDs are used for elevated body temperature (fever) against the background of infectious inflammatory diseases of the upper respiratory tract and ENT organs (tonsillitis, sinusitis, sinusitis, otitis), lower respiratory tract (bronchitis, pneumonia), influenza and colds.

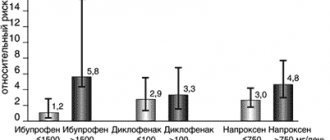

Risk of adverse drug reactions when using NSAIDs

Since the effectiveness of NSAIDs in therapeutic doses is comparable, when choosing NSAIDs for a particular patient, we proceed from the possible risks of developing ADRs (Table 1) [1]. Risk factors for the development of ADRs when using NSAIDs are: age over 60 years, overweight, smoking, history of gastric and duodenal ulcers, history of venous thrombosis and thromboembolism, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral atherosclerosis, arterial hypertension, lipid metabolism disorders , diabetes mellitus, diseases of the intestines, liver, kidneys, blood, congestive heart failure, chronic alcohol intoxication, combined use of medications that interact with NSAIDs, lactation. For a more differentiated selection of NSAIDs, a special algorithm was proposed, which involves the prescription of selective NSAIDs to patients with risk factors for developing gastrointestinal complications and the use of NSAIDs with a less pronounced toxic effect on the cardiovascular system in patients with high cardiovascular risk, as well as the prescription protective therapy (Table 2) [1].

According to Russian recommendations for the rational use of NSAIDs:

- the main method of preventing the development of ADRs when using NSAIDs is taking into account risk factors, their correction (if possible) and prescribing NSAIDs with a more favorable gastrointestinal (recommendation grade A) and cardiovascular safety profile (recommendation grade B);

- an additional method of preventing complications from the upper gastrointestinal tract is the prescription of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) (grade of recommendation A);

- an additional method for preventing complications from the upper gastrointestinal tract, small and large intestine can be the prescription of rebamipide (gradation of recommendation B);

- There are no effective drug methods of nephro- and hepatoprotection to reduce the risk of NSAID-associated complications.

pharmachologic effect

NSAIDs block the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX), which is involved in the formation of special mediators (transmitters) of inflammation, pain and fever - prostaglandins.

COX exists in two forms: COX-1 (or physiological - is formed in the body normally; is responsible for blood flow in the kidneys, the formation of protective mucus in the stomach, blood clotting, uterine tone) and COX-2 (or pathological - appears in the body only when inflammation; responsible for the development of edema, pain, increased body temperature).

Valuable pharmacological effects of NSAIDs (anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, analgesic) are associated with inhibition of COX-2, and negative side effects (formation of stomach ulcers, thrombosis or bleeding, impaired renal function, weakness of labor) are associated with inhibition of COX-1.

Introduction

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are among the most commonly used medications, both among prescription drugs and among over-the-counter drugs, i.e., used by patients themselves for self-medication without prescription. The frequency of use of NSAIDs in clinical practice is due to the spectrum of their pharmacological effects: analgesic, anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, antiaggregation (acetylsalicylic acid). However, a wide range of therapeutic effects and high clinical effectiveness also have a downside: NSAIDs are among the group of drugs that most often cause adverse drug reactions (ADRs) associated with toxic effects, hypersensitivity, drug and food interactions. Therefore, the clinician faces a difficult task: selecting NSAIDs for a specific patient.

The choice of drug is carried out according to a certain algorithm.

- Determination of indications for use of a medicinal product , which is determined by the clinical diagnosis of the patient: the underlying disease, the presence of comorbid pathology, complications, concomitant diseases. Of great importance is the assessment of risk factors for the development of complications of drug therapy: allergy history; previously identified symptoms of drug intolerance; concomitant therapy, including the use of herbal remedies, vitamin preparations, over-the-counter medications, dietary supplements; the patient's dietary preferences, alcohol abuse, smoking.

- Having determined the indication (“problem” of the patient), the doctor selects a group of drugs and a specific drug within this group, based on the criteria of effectiveness, safety, cost and ease of use.

- Having decided on the choice of a specific drug, the doctor chooses the mode of use of the drug: dose, frequency of use, duration of therapy.

- The doctor explains to the patient in an accessible form what is wrong with him and why the symptoms that bother him appeared, provides information about possible non-drug methods for correcting the pathological condition, explains to the patient why this drug was chosen and what the patient should pay attention to when using this drug, if any symptoms, he should immediately consult a doctor and even stop taking the drug. Almost 50% of cases of ineffective pharmacotherapy are due to low patient compliance, which is why it is so important to achieve cooperation with the patient and his compliance with the drug therapy regulations.

- During the treatment process, the doctor himself evaluates the effectiveness and safety of the pharmacotherapy being carried out, decides on the indications for prescribing protective therapy, stopping/prolonging treatment when the goal is achieved, or changing the drug if it is ineffective.

The implementation of this algorithm is possible only if the doctor is well aware of the indications for use and the clinical and pharmacological properties of the selected drug.

Classification of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

NSAIDs are classified according to the degree of selectivity of their action on COX, as well as according to their chemical structure:

- Non-selective inhibitors of COX-1 and COX-2 (non-selectively block both COX-1 and COX-2 to the same extent): salicylates: acetylsalicylic acid, lysine acetylsalicylate;

- acetic acid derivatives: diclofenac, indomethacin, aceclofenac, etodolac, amtolmetin guacil;

- propionic acid derivatives: ibuprofen, naproxen, ketoprofen, flurbiprofen, dexibuprofen, dexketoprofen;

- fenamates: mefenamic acid.

- oxicams: piroxicam, tenoxicam, lornoxicam, meloxicam;

Heat, pain, inflammation: why are NSAIDs needed, what are they and how do they work?

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are one of the most ancient groups of drugs that have retained their position in our 21st century. They have a “natural” origin, a difficult history of formation and incredible popularity among both doctors and patients.

From time immemorial

Mentions of the ancestors of NSAIDs are found in the first written sources that have reached us, which means we can safely assume that humanity was very familiar with plant raw materials with the necessary characteristics long before the advent of writing. Myrtle and willow, which appear both on Sumerian tablets and in the writings of ancient doctors, do contain a large number of natural salicylates, so it is not surprising that their infusions and decoctions helped to temporarily relieve pain and bring down high fever.

NSAIDs are a perfect illustration of how scientific medicine incorporates everything that actually works. First in a plant form, and since the end of the 19th century - in the form of a purified and modified chemical substance, this group of drugs in any conditions invariably demonstrates three strongly interconnected effects: anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic. In addition, the exact mechanism of action of aspirin, the first NSAID, became known only more than 70 years after the drug appeared on the market, which did not prevent us from assessing its direct and side effects in clinical practice, and adjusting the dosage and frequency of administration in different groups of patients.

Aspirin, created in German laboratories, had both undoubted advantages and tangible disadvantages, which pushed developers to search for new, no less effective, but less problematic means. This is how British ibuprofen and American indomethacin appeared, and the discovery of the mechanism of action of NSAIDs led to the emergence of a new generation of drugs that selectively act at the molecular level. Today this is the most popular group of drugs, both in terms of prescriptions and in terms of sales. Thus, in 2021, 24 international nonproprietary names (INN) of this group were presented on the Russian market in the form of 512 drugs, including combination drugs1, while they occupy 3% of the drug market in value terms and about 9% in terms of packages2.

It should be separately noted that the equally popular drug paracetamol (acetaminophen) does not belong to the group of NSAIDs, since it most likely has a different mechanism of action. Until it is definitely established, paracetamol is considered as a separate independent remedy. However, due to the similarity of effects and indications for use, in this review we will mention both NSAIDs and paracetamol together.

Enzymes are our everything

Direct and side effects of NSAIDs are directly related to one very interesting biochemical process that occurs in our body. Its discovery led to the awarding of the Nobel Prize to two Swedish researchers, Suna Bergström and Bengt Samuelson, and to the British pharmacologist John Robert Vane in 19823. The arachidonic acid cascade, which is what we are talking about, from a modern point of view looks like this:

Figure 1. Source: J Pharm Pharmaceut Sci.

11 (2): 81s-110s, 2008. Prostaglandins are biologically active substances, mediators of many pathological and, as it turned out later, physiological processes. If we talk about pathology, they are involved in the pathogenesis of inflammation, pain, hyperthermia and fever, malignant neoplasms, glaucoma, sexual dysfunction in men, osteoporosis, cardiovascular diseases, bronchial asthma4.

Arachidonic acid, where it all starts, is an omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid containing 20 carbon atoms that lives in the cell membrane as part of phospholipids. Under the influence of a wide range of stimuli and with the active assistance of the enzyme phospholipase A2, arachidonic acid is released from phospholipids, after which a cascade of its transformations begins with the participation of three enzymes - cyclooxygenase (COX), lipoxygenase (LOX) and cytochrome P450. As a result, a large number of biologically active substances-mediators are formed, called eicosanoids (their name comes from the Greek word “twenty” - according to the number of carbon atoms in arachidonic acid)5.

At the first stage, under the influence of LOX, leukotrienes are formed from part of the arachidonic acid; part, under the influence of COX, is converted into prostaglandin G2, which, in turn, under the action of highly specialized synthase enzymes, will give rise to thromboxanes A2 and prostaglandins D2; the remaining part, under the influence of peroxidase, will be converted into prostaglandin H2, the result of which will be prostaglandins E2, I2 and F2.

COX was first isolated in its pure form in 19766, and in the 90s it became clear that in the human body it is presented in at least two isoforms - COX-1, consisting of 602 amino acids, and COX-2, in which the “building blocks” two more7. Isoforms differ in their functions and final biologically active substances. To greatly simplify, we can say that COX-1 is the “good” COX, creating mainly anti-inflammatory agents, and COX-2 is the “bad” one, the result of its work is pro-inflammatory molecules8, 9, 10.

The first generation NSAIDs were non-selective; they inhibited both COXs at once, resulting in not only direct effects (temperature dropped, pain decreased), but also side effects - damage to the mucous membrane of the gastrointestinal tract, including bleeding, damage to the kidneys and liver. In the 1990s, selective NSAIDs were specially created that blocked only COX-2, which were indeed better tolerated, but it was not possible to completely get rid of all side effects.

Open palm strike

The body responds to many stimuli with a universal mobilization reaction—inflammation. The classic five signs, described by Celsus in the 1st century - calor, dolor, rubor, tumor, functio laesa (the last sign was added by Galen in the 2nd century AD - note "XX2 CENTURY"

), that is, increased temperature (local and/or systemic), pain, redness, swelling and dysfunction11. Since NSAIDs specifically inhibit the synthesis of inflammatory mediators, they are able to temporarily reduce all of the listed clinical manifestations, that is, the anti-inflammatory effect itself is the main one, and pain relief or a decrease in temperature is simply included in the package.

At equipotential doses, the main, that is, anti-inflammatory effect of all NSAIDs is approximately the same, that is, we cannot say that aspirin is more powerful than ibuprofen or that nimesulide is more effective than diclofenac. However, there are individual differences, with some patients responding better to one NSAID and worse to another. Often there is no explanation for this, as is the case with indomethacin, which can cause headaches and dizziness after a single dose in some people, but no such reaction in others12, 13.

What could be the reason for such differences? First of all, with absolute and relative differences in COX inhibition in different people, as well as with the action of other biological substances not related to prostaglandins. Secondly, with the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of specific dosage forms of NSAIDs, including pharmacogenetic factors that significantly affect the metabolism of a significant part of drugs in the human body14.

But if we talk about the analgesic effect, it will already differ significantly. For example, if we compare various NSAIDs according to the Oxford League criteria for acute pain15, it turns out that the weakest painkiller among single drugs for this indication will be ibuprofen at a dose of 50 mg (4.7 versus placebo; the lower the number, the more pronounced the effect of the drug in the study was ), and from the combined ones - aspirin 650 mg + codeine 60 mg (5.3). There are still a lot of interesting things there, for example, 1000 mg of paracetamol, since we agreed to mention it, is logically a little better at pain relief than 600 mg (3.8 versus 4.6), but not 2 times. By the way, even the synthetic opioid tramadol at a dosage of 50 mg copes poorly with the task (8.3). The best analgesics include the selective COX-2 inhibitor etoricoxib 180/240 mg (1.5) and diclofenac 100 mg (1.8). Of course, these criteria have their limitations, but they give a fairly indicative comparative picture - the spread is huge and, by and large, not particularly predictable. The antipyretic effect is even more complicated, it is more varied, and there is no single scale for assessing it, and it is one thing when they try to fight malaria fever in adults with the help of NSAIDs16, and quite another thing when the same fever occurs, but in other cases in children from 3 months to 2.5 years17.

Friendly Fire

If there is a pronounced direct effect, there must also be side effects - an immutable rule of pharmacology. NSAIDs affect enzymes that, by and large, perform their physiological functions, so limiting their work throughout the body entails a whole bunch of unpleasant consequences.

| Major side effects of NSAIDs18, 19, 20, 21, 22 | |

| Gastrotoxicity |

|

| Cardiotoxicity |

|

| Nephrotoxicity |

|

| Hepatotoxicity |

|

| Neurotoxicity |

|

| Hemotoxicity |

|

| Others |

|

Historically, gastrointestinal toxicity was the first to be described; it has been known for at least 60 years, and the first NSAID to fail in this sense was aspirin, even the term “aspirin ulcer” appeared. Yes, indeed, it is theoretically possible to assume a mechanism of direct damage to the mucosa by non-selective NSAIDs. Thus, aspirin, ibuprofen, naproxen, indomethacin and ketorolac are chemically carboxylic acids; at an acidic pH of the gastric environment, they do not ionize and can easily penetrate the gastric mucosa, where the pH of the environment is already in the zone of neutral values. Here they can ionize and temporarily linger in the epithelial cells, causing their damage. However, such a local effect most likely does not have a decisive significance, because even with intravenous or intramuscular administration of the listed NSAIDs, phenomena of gastrotoxicity are still observed23. So, most likely, this is due to their systemic action, that is, inhibition of “good” COX, which also produces protective agents24. Selective COX inhibitors do not have gastrointestinal toxicity25.

The reason for discussing the next group of side effects on the cardiovascular system was the scandal with the drug rofecoxib (Vioxx). This selective COX-2 inhibitor from the new coxib family received marketing approval from the FDA in May 1999,26 and on September 30, 2004, the drug's manufacturer issued an emergency recall from markets worldwide following post-marketing surveillance results from the APPROVe study. It turned out that users of rofecoxib had a significantly increased risk of developing a heart attack. One of the FDA analysts even calculated that over 5 years on the market, the drug could cause 88-139 thousand heart attacks with a mortality rate of 30-40%, but the FDA quickly disowned such radical conclusions and stated that this estimate was based solely on a mathematical model, so it should be interpreted with caution27.

Investigations began, doctors and regulators began to take a closer look at other representatives of the group and it turned out that cardiotoxicity can be considered their group “trick”; it is present in both selective and non-selective NSAIDs. In 2021, Danish scientists published the result of an analysis of 252 national cohort studies, showing a significant increase in the risk of adverse cardiovascular events while taking diclofenac compared to paracetamol, ibuprofen and naproxen28. The results of these and several other prospective and retrospective studies have led to a gradual re-evaluation of the risk-benefit profile of NSAIDs in patients with cardiovascular disease. However, attempts to determine the safest or, conversely, the most dangerous drug for the heart were not successful, the data obtained turned out to be too heterogeneous, and Tremeau Pharmaceuticals

, which currently owns the rights to Vioxx, announced plans in March 2019 to return the drug to the market29.

Myths and legends

One of the most common claims about ibuprofen that is not true is that it was discovered during the search for an effective hangover cure . A simple fact check leads us to an article by The Telegraph

30 about Stuart Adams, head of the group developing a safer alternative to aspirin at the British

Boots Group

, where he directly says that he tested his development himself in 1971, when he was preparing for an important report at a conference and suffered from a hangover. The drug itself was created in 1961 and appeared on the British market in 1969.

There is COX-3 . So far, the semi-legendary molecule was found in dogs by Simmons et al. in 200231. They identified it as a COX-1 splice variant. Theoretically, this could explain the analgesic effect of paracetamol, since it is well known that at therapeutic concentrations it inhibits COX-1 and COX-2 very, very poorly. The gene that encodes COX-3 in dogs, in humans and rodents, is responsible for the synthesis of a protein with a completely different amino acid sequence that is not even close to similar in its effects to COX-1 or COX-2. Thus, the clinical relevance of COX-3 as a target for NSAIDs is still an open question32, 33.

Metamizole sodium (Analgin) causes agranulocytosis . Developed in Germany and patented in 1922 under the trade name Novalgin,34 it was widely used throughout the world, but in the 1970s, at the height of the marketing war between American paracetamol and British ibuprofen, metamizole was accused of causing severe and frequent side effects. - agranulocytosis, damage to the blood system with an almost complete absence of leukocytes-granulocytes.

Nikita Zhukov’s “Drug Hit List” says the following about the drug35:

“Analgin (Metamizole/Metamizole/Dipyrone): has proven effectiveness, but it also has proven unsafety - somewhere in 1 in 1500-3000 cases of use it leads to agranulocytosis, which gives a 7% chance of dying (both with and without medical care You can safely multiply by 10).”

Moreover, there is a link only to the first figure, a 2002 study about the frequency of cases36. Yes, the percentages there are terrible, and the frequency is quite high, but the data is only for Sweden and only for pharmacy sales. However, if you look at the absolute numbers, the situation changes a little:

Figure 2.

Fatalities are shown in black, with only 2 of 15 deaths in 33 years of use of the drug as an antipyretic, and from 1979 to 1999 there were no deaths at all. And if we look at recent reviews (namely reviews, and not reports of individual cases, as in the Swedish study), it turns out that with short-term use, metamizole is no more dangerous than all other NSAIDs and paracetamol, and in some places even safer, this is also evidenced by data from 2015 37, and 201638. At the same time, Swedish data on the frequency of agranulocytosis have never been confirmed by anyone else. By the way, of all NSAIDs, only metamizole sodium has a central antipyretic effect; it acts on the hypothalamus, increasing heat transfer, which is why it is still in the kits of Russian “first aiders” as part of an injectable “lytic mixture” to combat temperatures around 40 ° C when other NSAIDs fail.

Paracetamol is the best hangover cure . This is already the second representative of NSAIDs with an “alcoholic” history and the second time it’s missed. Firstly, studies have shown at least some effect in alleviating hangover symptoms only for tolfenamic acid39. Secondly, paracetamol is the world champion in medicinal hepatitis. In the United States alone, about 30 thousand paracetamol hepatitis are admitted to hospitals per year, and a significant percentage of them require a liver transplant40.

Figure 3. Source.

We do not know why part of the metabolism of paracetamol (about 15%) follows the path of N-hydroxylation followed by dehydrogenation. But the fact remains: the output we get is N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), a powerful thiol poison that attacks -SH groups. Some of which immediately binds to glutathione, and some go to inactivate enzymes and damage disulfide bridges. RNA and DNA are also lost because DNA and RNA polymerases fail. And part of the drug is metabolized by cytochrome CYP3A4, and also with the formation of NAPQI41. As a result, the hepatotoxicity of paracetamol is added to the hepatotoxicity of ethanol, which does not improve the situation.

It is better to take NSAIDs with coffee . But this is the truth. Caffeine is an excellent adjuvant for this group of drugs and paracetamol; it enhances their analgesic effect through an as yet unknown mechanism. There is an assumption that some interaction occurs at the pharmacokinetic level42, but regardless of our knowledge of how everything happens at the molecular level, the clinical effect is confirmed even in Cochrane reviews43. This is why caffeine is included in some combination pain medications.

Summary for patients

NSAIDs are a group of drugs of natural origin, proven over more than a century, that temporarily reduce pain, inflammation and reduce elevated body temperature with a high-quality evidence base.

NSAIDs perform best over a short distance, when used in short courses of 3-5 days.

For some diseases, NSAIDs can be taken for a long period, weeks and months, but then side effects come to the fore, in this case, together with the doctor, it is necessary to select the minimum effective dose of a particular drug.

The vast majority of NSAIDs are available without a prescription and are good to have in your home medicine cabinet, but should not be abused. It is also necessary to carefully read the attached instructions and not exceed the recommended doses, frequency and duration of administration. If the problem is not resolved within 3-5 days, medical intervention is required.

With caution, preferably after first consulting with a doctor, NSAIDs can be taken by people with a peptic ulcer, as well as a history of gastrointestinal bleeding, coronary artery disease, heart failure, arterial hypertension, those who have had a stroke, kidney disease, or cirrhosis of the liver.

The same applies to older people, pregnant women in the last trimester and breastfeeding - not all NSAIDs can be used at this time.

Please note that NSAIDs cannot be combined with many medications, for example, some medications for high blood pressure, warfarin, and antidepressants - selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Specific information can be found in the instructions or checked with your doctor. The same applies to alcohol, herbal remedies and dietary supplements containing St. John's wort and gingko biloba.

Take into account contraindications, as well as age restrictions, most NSAIDs are not used in pediatric practice, the same aspirin in the Russian Federation is allowed from 15 years, metamizole sodium - from 15 years, nimesulide - from 12 years.

Classification of NSAIDs

- Salicylates acetylsalicylic acid (“Aspirin”, “Taspir”, “Trombo ACC”, “Upsarin Upsa”, “Acecardol”)

- diflunisal (“Diflunisal”, “Onofrol-Sanovel”)

- trisalicylate (choline-magnesium trisalicylate, "Trilisate")

- benorylate ("Benoral")

- sodium salicylate

- flufenamic acid (“Opirin”)

- ibuprofen (Advil, Bonifen, Brufen SR, Burana, Dolgit, Ibalgin, Ibunorm, Ibuprom, Ibufen, Ibumetin, MIG 400, Nurofen ", "Solpaflex", "Faspik")

- withdrawn from sale in 1982 by the manufacturer for safety reasons)

- diclofenac (“Voltaren”, “Vurdon”, “Diklak”, “Dicloberl”, “Dolex”, “Clodifen”, “Naklofen”, “Olfen”, “Ortofen”)

)

- tolmetin ("Tolectin")

)

- indomethacin (“Indovazin”, “Eftimethacin”, “Indocollir”, “Metindol”)

)

- phenylbutazone (Butadione, Ambenium-Trivium)

- piroxicam (“Piroxyfer”, “Finalgel”, “Feldoral SEDICO”, “Erazon”, “Remoxicam”, “Hotemin”, “Calmopirol”)

- proquazon

; also included in the complex preparations “Proctosan”, “Proctozol”)

)

- celecoxib (Celebrex, Flogoxib, Dilaxa, Roucoxib-Routek)

- nimesulide (“Nise”, “Nimesil”, “Nimulid”, “Aktasulide”, “Aponil”, “Aulin”, “Kokstral”, “Mesulide”, “Nimegesik”, “Nimesubel”, “Nimid”, “Nimika”, "Prolid", "Remisid", "Flolid", "Nemulex")

Timeline of NSAID discoveries

2500 BC e. - a description of the use of myrtle leaves to treat fever on Sumerian clay tablets, it is now known that myrtle, like willow, contains large amounts of natural salicylates.

430-330 BC e. - mention of willow as a medicinal plant in the “Hippocratic Collection”.

30 year - Celsus’s description of the signs of inflammation and the use of willow bark to combat them.

1763 - Church of England priest Edward Stone describes the effectiveness of salicylate-containing plants for the treatment of intermittent fever (malaria) and complications of rheumatism.

1827 - isolation of salicin glycoside from willow bark by Johann Andreas Büchner, a German pharmacologist and alkaloid specialist.

1829 - French chemist Henri Leroux obtained 30 g of pure salicin from 1.5 kg of willow bark.

1869 - synthesis of salicylic acid by Hermann Kolbe, an outstanding German organic chemist.

1898 - the first use of acetylsalicylic acid for medical purposes.

1899 — registration of the drug acetylsalicylic acid under the name “Aspirin” (“a” - acetyl, “spirin” - from the outdated name of salicylic acid).

1940s - discovery of phenylbutazone, which gave rise to the group of butylpyrazolidines, widely used in the treatment of arthritis in the 1950s.

1961 - creation of ibuprofen.

1963 - creation of indomethacin.

1976 - discovery of the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX).

1982 - British pharmacologist John Robert Vane was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for describing the mechanism of action of NSAIDs (block of prostaglandin and thromboxane synthesis).

1991 - discovery of an isoform of the cyclooxygenase enzyme, COX-2.

1990s - creation of selective COX-2 inhibitors.

2002 - discovery of the COX-3 enzyme in the tissues of experimental animals.

Literature

1 Oleinikova T. A., Pozhidaeva D. N. Analysis of trends in the development of the pharmaceutical market of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in Russia // “Remedium”, No. 5, 2018; DOI: 10.21518/1561-5936-2018-5-14-20

2 DSM Group: dynamics of sales of analgesics in Russia. URL: https://dsm.ru/news/357/ (access date: 11/07/2019)

3 The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1982. URL: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1982/summary/ (access date: 11/07/2019)

4 Abramovitz, M., Metters, KM Prostanoid receptors // Ann. Rep. Med. Chem., 33:223-231, 1998.

5 W. L. Smith, D. L. DeWitt and R. M. Garavito. Cyclooxygenases: structural, cellular, and molecular biology // Ann Rev Biochem, 69:145-182, 2000.

6 T. Miyamoto, M. Ogino, S. Yamamoto and O. Hayaishin. Purification of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthetase from bovine vesicular gland microsomes // J Biol Chem, 259:2629-2636, 1976.

7 E. A. Meade, W. L. Smith and D. L. DeWitt. Differential inhibition of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase (cyclooxygenase) isozymes by aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs // J Biol Chem, 268:6610-6614, 1993.

8 C. C. Pilbeam, P. M. Fall, C. B. Alander and L. G. Raisz. Differential effects of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on constitutive and inducible prostglandin G/H synthase in cultured bone cells // J Bone Miner Res, 12:1198-1203, 1997

9 CD Breder, DL DeWitt and RP Kraig. Characterization of inducible cyclooxygenase in rat brain // J Comp Neurol, 355:296-315, 1995

10 H. F. Cheng, J. L. Wang, M. Z. Zhang, Y. Miyazaki, I. Ichikawa, J. A. McKanna and R. C. Harris. Angiotensin II attenuates renal cortical cyclooxygenase-2 expression // J Clin Invest, 103:953-961, 1999.

11 Ciaccia L. Fundamentals of Inflammation // Yale J Biol Med. 2011;84(1):64–65.

12 VanderPluym, J. Indomethacin-Responsive Headaches // Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep (2015) 15: 516. DOI: 10.1007/s11910-014-0516-y

13 Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Gupta M. Hemicrania continua: who responds to indomethacin? // Cephalalgia 2009;29:300-307

14 Rollason V, Samer CF, Daali Y, Desmeules JA. Prediction by pharmacogenetics of safety and efficacy of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a review // Curr Drug Metab 2014; 15:326.

15 Oxford league table of analgesics in acute pain. URL: https://www.bandolier.org.uk/booth/painpag/Acutrev/Analgesics/Leagtab.html (access date: 11/07/2019)

16 Meremikwu MM, Odigwe CC, Akudo Nwagbara B, Udoh EE. Antipyretic measures for treating fever in malaria // Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 9. Art. No.: CD002151. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002151.pub2.

17 Litalien, C. & Jacqz-Aigrain, E. Pediatr-Drugs (2001) 3: 817. DOI: 10.2165/00128072-200103110-00004

18 Meara AS, Simon LS (2013). Advice from professional societies: appropriate use of NSAIDs // Pain Med, 14 Suppl 1: S3-10

19 Carson JL, Strom BL, Duff A, et al. Safety of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with respect to acute liver disease // Arch Intern Med 1993; 153:1331.

20 Curhan SG, Shargorodsky J, Eavey R, Curhan GC. Analgesic use and the risk of hearing loss in women // Am J Epidemiol 2012; 176:544.

21 Mockenhaupt M, Kelly JP, Kaufman D, et al. The risk of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: a multinational perspective // J Rheumatol 2003; 30:2234.

22 Zhang X, Schwarz EM, Young DA, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 regulates mesenchymal cell differentiation into the osteoblast lineage and is critically involved in bone repair // J Clin Invest 2002; 109:1405.

23 Estes LL, Fuhs DW, Heaton AH, Butwinick CS. Gastric ulcer perforation associated with the use of injectable ketorolac // Ann Pharmacother 1993; 27:42.

24 van Oijen MG, Dieleman JP, Laheij RJ, et al. Peptic ulcerations are related to systemic rather than local effects of low-dose aspirin // Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6:309.

25 Loren Laine MD. The gastrointestinal effects of nonselective NSAIDs and COX-2—selective inhibitors // Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism Volume 32, Issue 3, Supplement, December 2002, Pages 25-32

26 VIOXX® (rofecoxib tablets and oral suspension). URL: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2004/21647_vioxx_lbl.pdf (access date: 11/07/2019)

27 FDA Official Admits 'Lapses' on Vioxx - The New York Times, March 2, 2005. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2005/03/02/politics/fda-official-admits-lapses-on- vioxx.html (date of access: 07.11.2019)

28 Schmidt Morten, Sørensen Henrik Toft, Pedersen Lars. Diclofenac use and cardiovascular risks: series of national cohort studies // BMJ 2018; 362:k3426

29 Tremeau Expands Leadership Team - 03/27/2019, URL: https://www.tremeaurx.com/news/2019/3/8/tremeau-expands-leadership-team (access date: 11/07/2019)

30 Dr Stewart Adams: 'I tested ibuprofen on my hangover' - The Telegraph, 08 Oct 2007. URL: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/health/3351540/Dr-Stewart-Adams-I-tested -ibuprofen-on-my-hangover.html (date of access: 11/07/2019)

31 N. V. Chandrasekharan, H. Dai, K. L. Roos, N. K. Evanson, J. Tomsik, T. S. Elton and D. L. Simmons. COX-3, a cyclooxygenase-1 variant inhibited by acetaminophen and other analgesic/antipyretic drugs: cloning, structure and expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 99:13926-13931, 2002.

32 RM Botting. Mechanism of action of acetaminophen: is there a cyclooxygenase 3? // Clin Infect Dis, 31: S202—S210, 2000.

33 B. Kis, J. A. Snipes and D. W. Busija. Acetaminophen and the cyclooxygenase-3 puzzle: sorting out facts, fictions, and uncertainties // J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 315:1-7, 2005.

34 MD Kay Brune. The early history of non-opioid analgesics // Acute Pain, Volume 1, Issue 1, December 1997, Pages 33-40; DOI: 10.1016/S1366-0071(97)80033-2

35 Drug hit list. URL: https://encyclopatia.ru/wiki/%D0%A0%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%81%D1%82%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%BB%D1%8C%D0 %BD%D1%8B%D0%B9_%D1%81%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%BA_%D0%BF%D1%80%D0%B5%D0%BF %D0%B0%D1%80%D0%B0%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%B2#.D0.90 (date of access: 11/07/2019)

36 Hedenmalm, K. & Spigset, O. Agranulocytosis and other blood dyscrasias associated with dipyrone (metamizole) // Eur J Clin Pharmacol (2002) 58: 265. DOI: 10.1007/s00228-002-0465-2

37 Thomas Kötter et al., Metamizole-Associated Adverse Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis // PLoS One. 2015; 10(4): e0122918. 2015 Apr 13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122918

38 S. Andrade et al., Safety of metamizole: a systematic review of the literature // Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 2016; Vol 41, Iss 5, 459-477; DOI: 10.1111/jcpt.12422

39 Kaivola S, Parantainen J, Osterman T, Timonen H. Hangover headache and prostaglandins: prophylactic treatment with tolfenamic acid // Cephalalgia 1983; 3:316

40 Yoon E, Babar A, Choudhary M, Kutner M, Pyrsopoulos N. Acetaminophen-Induced Hepatotoxicity: a Comprehensive Update // J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016;4(2):131–142. doi:10.14218/JCTH.2015.00052

41 Moyer AM, Fridley BL, Jenkins GD, et al. Acetaminophen-NAPQI hepatotoxicity: a cell line model system genome-wide association study // Toxicol Sci. 2011;120(1):33–41. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfq375

42 Vinicio Granados-Soto, Gilberto Castañeda-Hernández. A review of the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic factors in the potentiation of the antinociceptive effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs by caffeine // Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. Volume 42, Issue 2, October 1999, Pages 67-72

43 Derry CJ, Derry S, Moore RA. Caffeine as an analgesic adjuvant for acute pain in adults // Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014(12):CD009281. Published 2014 Dec 11. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009281.pub3