In modern medicine, bronchitis in children and its possible consequences are promptly diagnosed and successfully treated. Repeated, frequent bronchitis can occur in children if they live in conditions with a polluted atmosphere - in cities with developed industry and a small amount of green space. The incidence of bronchitis in children increases if someone smokes in the room where the child lives. Children and adolescents are more likely to suffer from this disease in the cold season, with sudden changes in temperature and humidity in the environment.

Bronchitis is an inflammatory process that occurs in the bronchi. Most often, inflammation in the bronchi affects almost all parts of the bronchial tree. That is, bronchitis is the spread of the inflammatory process in all bronchi, from the large lobar bronchi to the smallest, the internal diameter of which in children under 6 months is no more than 1 mm.

Causes of bronchitis in children

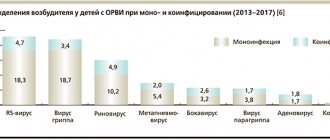

Acute bronchitis most often occurs when a child becomes infected with a viral infection. In such cases, bronchitis is caused by parainfluenza viruses, rhinovirus, and rhinosyncytial virus. Less commonly, viral bronchitis occurs in children when coronavirus, metapneumovirus, or bocaviruses enter the body.

The second most common cause of bronchitis is a bacterial infection. Bacterial bronchitis is caused by pneumococcus, mycoplasma, and chlamydia. Less commonly - Haemophilus influenzae or Moraxella. In a large number of children, the cause of acute bronchitis is a mixed flora, that is, inflammation occurs when both viruses and bacteria enter at the same time.

Another cause of acute bronchitis is the entry of food and stomach contents into the respiratory tract. This most often occurs in children under 6 months of age and occurs when the baby regurgitates and does not feed properly. This type of bronchitis is called aspiration bronchitis. Inflammation in the bronchial mucosa in this situation occurs for several reasons - the gastric contents act aggressively, as they contain hydrochloric acid and enzymes, and the introduction of gastric and intestinal microflora is also possible, which will cause bacterial bronchitis.

Differential diagnosis and therapy of broncho-obstructive syndrome in children

D.Yu. OVSYANNIKOV

, D.M.S.,

D.A.

KACHANOVA ,

Peoples' Friendship University of Russia, Moscow

The article presents modern information about broncho-obstructive syndrome in children, its etiology and pathogenetic mechanisms. The characteristics of the most common causes of bronchial obstruction - acute bronchiolitis (obstructive bronchitis) and bronchial asthma, as well as the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions for these diseases from the standpoint of evidence-based medicine are given. The differential diagnostic criteria for bronchial asthma and other obstructive airway diseases are listed. The therapeutic possibilities of the combination of fenoterol and ipratropium bromide, the advantages of nebulizer therapy for bronchial asthma are described.

Broncho-obstructive syndrome (BOS) is a pathophysiological concept characterized by impaired bronchial obstruction in patients with acute and chronic diseases. The term biofeedback cannot be used as an independent diagnosis; biofeedback is heterogeneous in nature and can be a manifestation of many diseases ( Table 1

).

| Table 1. Diseases occurring with biofeedback in children | |

| Acute diseases | Chronic diseases |

| Acute obstructive bronchitis/acute bronchiolitis Aspiration of foreign bodies (acute phase) Helminth infections (ascariasis, toxocariasis, pulmonary phase) Bronchial asthma | Bronchopulmonary dysplasia Bronchiectasis Aspiration bronchitis Cystic fibrosis Obliterating bronchiolitis Congenital malformations of the bronchi and lungs Vascular anomalies Congenital heart defects with pulmonary hypertension Gastroesophageal reflux disease |

The main pathogenetic mechanisms of bronchial obstruction include:

1) thickening of the bronchial mucosa as a result of inflammatory edema and infiltration; 2) hypersecretion and changes in the rheological properties of bronchial secretions with the formation of mucus plugs (obturation, the main mechanism of bronchial obstruction in bronchiolitis); 3) spasm of bronchial smooth muscles (the significance of this component increases with the age of the child and with repeated episodes of bronchial obstruction); 4) remodeling (fibrosis) of the submucosal layer (an irreversible component of bronchial obstruction in chronic diseases); 5) swelling of the lungs, increasing obstruction due to compression of the airways. These mechanisms are expressed to varying degrees in children of different ages with different diseases [1].

Common clinical signs of bronchial obstruction include tachypnea, expiratory shortness of breath with the participation of auxiliary muscles, noisy wheezing (in the English literature this symptom complex is called wheezing), chest swelling, wet or paroxysmal, spasmodic cough. With severe bronchial obstruction, there may be cyanosis and other symptoms of respiratory failure. Auscultation reveals scattered moist fine bubbling rales, dry wheezing, and with bronchiolitis - crepitus; percussion - boxy tint of percussion sound, narrowing of the boundaries of cardiac dullness. An X-ray examination of the chest reveals swelling of the lungs. Transcutaneous pulse oximetry allows you to objectify the degree of respiratory failure and determine indications for oxygen therapy, on the basis of which the degree of blood oxygen saturation (saturation, Sat O2) is determined ( Table 2

).

| Table 2. Classification of respiratory failure by severity [2] | |||

| DN degree | PaO2, mmHg Art. | Sat O2, % | Oxygen therapy |

| Norm | ≥80 | ≥95 | — |

| I | 60–79 | 90–94 | Not shown |

| II | 40–59 | 75–89 | Oxygen via nasal cannulas/mask |

| III | <40 | <75 | mechanical ventilation |

In respiratory infections, BOS is a manifestation of obstructive bronchitis (OB) or acute bronchiolitis - an infectious and inflammatory disease of the bronchi, accompanied by clinically pronounced bronchial obstruction. Acute bronchiolitis is a variant of acute obstructive bronchitis with damage to small bronchi and bronchioles in children of the first two years (most often the first six months) of life. The main etiological factors of AOB/bronchiolitis are respiratory viruses, most often respiratory syncytial virus. The onset of the disease is acute with catarrhal symptoms, body temperature is normal or subfebrile. Clinical signs of biofeedback may appear both on the first day and 2-4 days after the onset of the disease. In infants, especially premature infants, apnea may occur, usually early in the disease, before respiratory symptoms manifest [3]. Differences in the clinical presentation of AOB and bronchiolitis are presented in Table 3

.

| Table 3. Differential diagnostic signs of acute obstructive bronchitis and acute bronchiolitis in children [1 ] | ||

| Acute obstructive bronchitis | Acute bronchiolitis | |

| Age | More often in children older than 1 year | More often in infants |

| Broncho-obstructive syndrome | From the onset of the disease or on the 2-3rd day of the disease | On the 3-4th day from the onset of the disease |

| Wheezing | Expressed | Not always |

| Dyspnea | Moderate | Expressed |

| Tachycardia | No | Eat |

| Auscultatory picture in the lungs | Whistling, moist fine bubbling rales | Wet fine rales, crepitus, diffuse weakening of breathing |

Bronchial asthma (BA) is the most common chronic lung disease in children. Currently, BA in children is considered as a chronic allergic (atopic) inflammation of the respiratory tract, accompanied by increased sensitivity (hyperreactivity) of the bronchi and manifested by attacks of difficulty breathing or suffocation resulting from widespread narrowing of the bronchi (bronchial obstruction), caused by bronchospasm, increased secretion of mucus, swelling of the bronchial mucosa. Bronchial obstruction in patients with asthma is reversible spontaneously or with treatment [4].

Asthma is likely in the following patients:

— with atopic dermatitis in the first year of life; — with the development of the first episode of biofeedback over the age of 1 year; - with high levels of general/specific IgE or positive results of skin allergy tests, peripheral blood eosinophilia; - having parents, and to a lesser extent other relatives, with atopic diseases; - who have suffered three or more episodes of bronchial obstruction, especially without a rise in body temperature and after contact with non-infectious triggers; - with night cough, cough after physical activity; - with frequent acute respiratory infections that occur without an increase in body temperature.

It is also necessary to evaluate the effect of elimination and use of β2-agonists, antihistamines, glucocorticosteroids (rapid positive dynamics of clinical symptoms of bronchial obstruction after cessation of contact with a causally significant allergen, for example during hospitalization, after the use of these drugs). A risk index for the development of asthma in children has been proposed ( Table 4

).

| Table 4. Risk index for asthma in children [5 ] | |

| More than 3(4) episodes of wheezing in the past year | |

| One big criterion One of the parents has a confirmed diagnosis of asthma Atopic dermatitis in the child Sensitization to at least one aeroallergen | or two minor criteria Food allergy Blood eosinophilia (>4%) Wheezing not associated with infection |

The use of this index demonstrated high reliability of the prognosis: 76% of children with a positive prognostic index of asthma aged 6-13 years had at least one exacerbation of asthma and, on the contrary, 95% of children with a negative prognostic index did not suffer from asthma over the age of 6 years [5 ].

A great achievement in the development of diagnostic criteria for asthma in childhood was the International Guidelines for asthma in children of a working group of 44 experts from 20 countries PRACTALL (Practical Allergology) Pediatric Asthma Group. According to this document, persistent asthma is diagnosed when biofeedback is combined with the following factors: clinical manifestations of atopy (eczema, allergic rhinitis, conjunctivitis, food allergy), eosinophilia and/or elevated levels of total IgE in the blood; specific IgE-mediated sensitization to food allergens in infancy and early childhood and to inhalation allergens in the future; sensitization to inhalant allergens under the age of 3 years, primarily with sensitization and high levels of exposure to household allergens at home; presence of asthma in parents [6]. In this regard, it should be noted that GINA experts (2011) do not consider an increase in total IgE a marker of atopy due to the high variability of this indicator [7].

A number of clinical, anamnestic and laboratory-instrumental signs make the diagnostic hypothesis more likely that the biofeedback in this patient is not asthma, but is a manifestation of other diseases (Table 1). These signs include the following:

- onset of symptoms from birth; — artificial ventilation, respiratory distress syndrome in the neonatal period; - neurological dysfunction; - lack of effect from glucocorticosteroid therapy; - wheezing associated with feeding or vomiting, difficulty swallowing and/or vomiting; - diarrhea; - poor weight gain; - long-term oxygen therapy; - deformation of fingers (“drumsticks”, “watch glasses”); - heart murmurs; - stridor; - local physical and radiological changes in the lungs; - cyanosis; — irreversibility of airway obstruction according to the results of a respiratory function test; - persistent radiographic changes.

Thus, with biofeedback occurring with relapses, the child needs an in-depth examination to clarify the diagnosis. Until recently, in Russia, along with the term “acute obstructive bronchitis” (AOB), the term “recurrent obstructive bronchitis” (ROB) was used (in accordance with the 1995 classification of bronchopulmonary diseases in children). The 2009 revision of this classification excluded this diagnosis due to the fact that asthma and other chronic diseases that require timely diagnosis often occur under the guise of RRD [8].

Table 5

The clinical features of patients with alternative diagnoses of respiratory diseases relative to asthma are presented. The listed signs are usually absent in children with asthma.

| Table 5. Clinical features of alternative diagnoses in children with biofeedback (adapted) [9 ] | |

| Peculiarities | Possible diagnosis |

| Symptoms present from birth | Cystic fibrosis, primary ciliary dyskinesia, congenital malformations, bronchopulmonary dysplasia |

| Repeated pneumonia | Cystic fibrosis, neuromuscular disorders, primary ciliary dyskinesia, immunodeficiency states |

| Severe sinusitis | Immunodeficiency conditions, primary ciliary dyskinesia, cystic fibrosis |

| Persistent wet cough | Cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, primary ciliary dyskinesia, immunodeficiency states |

| Nausea, vomiting | Gastroesophageal reflux (± aspiration) |

| Dysphagia | Swallowing difficulty (± aspiration) |

| Dizziness, weakness, ringing in the ears | Hyperventilation syndrome/panic attacks |

| Inspiratory stridor | Diseases of the trachea or larynx |

| Changing voice or crying | Diseases of the larynx |

| Fingers shaped like “drumsticks” | Bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis |

| Local or persistent radiographic changes | Congenital malformations, cystic fibrosis, foreign body, bronchiectasis, tuberculosis, bronchiolitis obliterans |

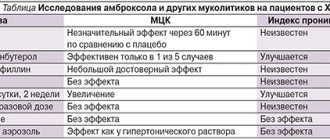

The first-line drugs for biofeedback are inhaled bronchodilators. The response to these drugs, taking into account the polyetiology and heterogeneity of the pathogenesis of BOS, is variable and depends on the disease the patient has. Thus, there is no evidence of the effectiveness of bronchodilators and glucocorticosteroids in patients with acute bronchiolitis (both inhaled and oral) [10]. It should be noted that according to international recommendations - the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Scottish Intercollegial Guidelines Exchange Network (SIGN) - for most other commonly used interventions for acute bronchiolitis, there is no evidence that they reduce the severity, duration of the disease, shorten the length of hospitalization and influence the outcome. In this regard, these interventions are not recommended (Table 6). There was no data available on the effectiveness of hypertonic NaCl solution in patients with bronchiolitis.

| Table 6. AAP and SIGN recommendations for the treatment of acute bronchiolitis [11, 12 ] | ||

| AAP | SIGN | |

| Inhaled albuterol (salbutamol) | No | No |

| Inhaled adrenaline | No | No |

| Inhaled ipratropium bromide | No | No |

| Systemic corticosteroids | No | No |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | No | No |

| Inhaled ribavirin | Not for everyday use | No |

| Antibiotics | No | No |

| Oxygen | Yes, when SatO2 < 90% | Yes, when SatO2 < 92% |

| Breathing physiotherapy | No | No |

| Superficial nasal aspiration | Yes | Yes |

| Adding Liquid | Yes, if feeding is difficult | Yes, if feeding is difficult |

Treatment of asthma is based on the “three pillars” - limiting contact with allergens (in a complex of elimination measures), treatment for exacerbation of the disease and basic control anti-inflammatory therapy. The same classes of drugs are used to treat asthma in children as in adults. However, the use of existing drugs in children is associated with certain limitations. To a large extent, these features relate to the means of delivering inhaled drugs to the respiratory tract.

In children, the use of metered-dose aerosol inhalers with bronchodilators is often difficult due to age characteristics and the severity of the condition, which affects the dose reaching the lungs and, consequently, the response. Metered aerosol inhalers require precise technique, which not only children, but also adults are not always able to master.

During an exacerbation, less coordination is required when using a spacer. In children aged 5 years and younger, the use of a spacer with a face mask is recommended for the administration of inhaled drugs. This method is simpler than using a metered dose inhaler, but is subject to variability in drug delivery depending on the device used. Nebulizers do not require patient coordination or cooperation to the same extent as other delivery devices and are therefore the recommended devices for the administration of β2-agonists/M-anticholinergics, as well as budesonide, cromoglycic acid in young children. Preference is given to compression and membrane nebulizers (ultrasonic nebulizers do not achieve the required exposure of drugs and some drugs are destroyed).

The advantages of nebulizers, in contrast to other delivery vehicles, are the absence of the need to coordinate inhalation and inhalation, the ability to carry out high-dose therapy in seriously ill patients, the absence of freon, and the generation of a highly dispersed aerosol. The clinical advantages of nebulizer therapy include confidence that the patient is receiving an adequate dose of the drug, non-invasiveness, unmatched rapid relief of attacks of difficulty breathing, the ability to use for life-threatening symptoms, the ability to use in hospital and outpatient settings (in the latter case, the likelihood of hospitalization is reduced), and risk reduction systemic action of the drug.

To relieve acute bronchial obstruction in patients with asthma, β2-agonists (formoterol, salbutamol, fenoterol), anticholinergic drugs (ipratropium bromide), and methylxanthines are used. The leading mechanisms of reversible bronchial obstruction in children with asthma are spasm of bronchial smooth muscles, hypersecretion of mucus and swelling of the mucous membrane. The latter mechanism is the leading one in young children. However, the effect of bronchodilators on these mechanisms of bronchial obstruction is different. Thus, β2-agonists and aminophylline have a predominant effect on bronchospasm, and M-anticholinergics - on swelling of the mucous membrane. This heterogeneity of action of different bronchodilators is associated with the distribution of adrenergic receptors and M-cholinergic receptors in the respiratory tract. In the small-caliber bronchi, in which bronchospasm predominates, β2-adrenergic receptors are predominantly represented, in the medium and large bronchi with the predominant development of edema of the mucous membrane - cholinergic receptors. These circumstances explain the need, effectiveness and advantages of combined (β2-agonist/M-anticholinergic) bronchodilator therapy in children.

The use of ipratropium bromide in the treatment of children with acute asthma in the emergency department in combination with β2-agonists improves respiratory function, reduces the time and number of nebulizer inhalations, and reduces the frequency of subsequent visits. In a review study in children under 2 years of age, a significant effect of an aerosol anticholinergic drug was not proven, but there was an effect of using a combination of ipratropium bromide and a β2-agonist [13]. In a systematic review of 13 randomized controlled trials that included children with asthma at 18 months of age. - 17 years, in severe attacks of the disease, the use of multiple inhalations of ipratropium bromide in combination with a β2-agonist (eg, fenoterol) has been shown to improve FEV1 and reduce hospitalization to a greater extent than β2-agonist monotherapy. In children with mild to moderate attacks, this therapy also improved respiratory function [14]. In this regard, inhaled ipratropium bromide is recommended in children with exacerbation of asthma, especially in the absence of a positive effect after initial use of inhaled β2-agonists.

According to the recommendations of GINA (2011) and the Russian national program “Bronchial asthma in children. Treatment strategy and prevention” (2013), a fixed combination of fenoterol and ipratropium bromide is the drug of choice in the treatment of exacerbations, which has proven itself in children of any age [4, 7]. With the simultaneous use of two active substances, bronchial dilatation occurs through two different pharmacological mechanisms: ipratropium bromide (M-anticholinergic), whose action is primarily aimed at the proximal respiratory tract, and fenoterol (selective β2-agonist), acting in the distal respiratory tract. To achieve a bronchodilator effect when using this combination, a lower dose of the β-adrenergic component is required, which allows almost completely avoiding side effects. At the same time, the bronchodilator effect when using a combination of fenoterol and ipratropium bromide is higher than that of the original drugs, develops quickly (after 3-5 minutes) and is characterized by a duration of action of up to 8 hours. The use of this drug allows you to reduce the dose of monocomponents (β2-agonists) [ 15].

At the moment, there are two pharmaceutical forms of this drug - a metered dose aerosol inhaler and an inhalation solution. The presence of various forms of drug delivery allows its use in various age groups, starting from the first year of life. A small dose of fenoterol in combination with an anticholinergic drug provides high efficacy and a low incidence of side effects. A solution of this multicomponent drug (fenoterol and ipratropium bromide) is used for inhalation through a nebulizer in children under 6 years of age at a dose of 0.5 ml (10 drops) up to 3 times a day or 50 mcg of fenoterol per kg of body weight in one dose (but not more than 0.5 ml), for children over 6 years old - 10-20 drops up to 4 times a day. The recommended dose is diluted with saline solution.

The use of a fixed combination of fenoterol and ipratropium bromide promotes rapid relief of an attack, restoration of peak expiratory flow rates and a clear regression of clinical symptoms of exacerbation of asthma in children.

Literature

1. Ovsyannikov D.Yu. Acute bronchiolitis in children. Questions of practical pediatrics. 2010, 5(2): 75-84. 2. Avdeev S. N. Respiratory failure: definition, classification, approaches to diagnosis and therapy. Respiratory medicine. Ed. A.G. Chuchalina. M.: GEOTAR-Media, 2007, 2: 658-668. 3. Ovsyannikov D.Yu., Degtyarev D.N., Korsunsky A.A. et al. Respiratory syncytial viral bronchiolitis in premature infants in clinical practice. Pediatrics, 2014, 93 (3): 34-40. 4. National program “Bronchial asthma in children. Treatment strategy and prevention" M.: Original layout, 2013: 184. 5. Castro-Rodriguez JA et al. A clinical index to define the risk of asthma in young children with recurrent wheezing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 162: 1403-1406. 6. Geppe N.A., Revyakina V.A. New international recommendations for bronchial asthma in children PRACTALL. Atmosphere. Pulmonology and allergology. 2008, 1: 60-68. 7. Global strategy for the treatment and prevention of bronchial asthma (revision 2011). Ed. A.S. Belevsky. M.: RRO, 2012: 108. 8. Classification of clinical forms of bronchopulmonary diseases in children. M.: RRO, 2009: 18. 9. Kolkhir P.V. Evidence-based allergology-immunology. M.: Practical Medicine, 2010: 528. 10. Baraldi E., Zanconato S., Carraro S. Bronchiolitis: from empiricism to scientific evidence. Attending doctor. 2011, 6: 36-42. 11. American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Diagnosis and Management of Bronchiolitis. Diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics, 2006, 118: 1774-93. 12. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Bronchiolitis in children. NHS Quality Improvement Scotland [Internet] Available from www.sign.ac.uk. 13. Callahan S, Canny G, Lcvison H. Efficacy of frequent nebulised ipratropium bromide added to frequent high-dose albuterol therapy in severe childhood asthma. Pediatr. 1995, 126: 639-645. 14. Plotnick LH, Ducharme FM. Combined inhaled anticholinergics and b2 agonists in the initial management of acute pediatric asthma. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2001. Oxford: Update Software. Search date 2000; primary sources Medline, Embase, Cinahl, hand searches of bibliographies of references, and contact with pharmaceutical companies for details of unpublished trials and personal contacts. 15. Malakhov A.B., Zheludkova V.P., Makarova S.A. and others. The effectiveness of nebulizer therapy for exacerbations of bronchial asthma in children at the prehospital stage. Pulmonology, 2000, 4: 67-72.

Source

: Medical Council, No. 1, 2015

Forms of bronchitis

There are several forms of bronchitis along the way:

- Acute bronchitis is an acute inflammation of the bronchial mucosa.

- Recurrent bronchitis – when a child experiences bronchitis 2-3 times a year.

- Chronic bronchitis is a chronic widespread inflammatory lesion of the bronchi. In this case, the child experiences 2-3 exacerbations of the disease during the year and this continues for at least two or more years in a row.

Fortunately, chronic bronchitis practically never occurs in children. But there are a number of chronic diseases that occur with similar symptoms.

Danger

Acute obstructive bronchitis is well treated. If a child is prone to allergies, the disease can often recur, which can lead to the development of bronchial asthma or asthmatic bronchitis. If the disease becomes chronic, the prognosis is less favorable.

In 5% of cases, the disease is accompanied by a secondary infection that affects one or two lungs at once. Then pneumonia is diagnosed. Most often, complications of obstructive bronchitis occur in smokers, people with weakened immune systems, and people with liver, kidney and heart diseases. It can be:

- respiratory failure;

- emphysema;

- amyloidosis (disorder of protein metabolism in tissues);

- pulmonary heart.

If the patient begins to choke, feels severe weakness, and refuses to eat, an urgent consultation with a pulmonologist is necessary. In severe cases, hospitalization may be required.

Symptoms of bronchitis

When infected with a virus

Acute bronchitis of viral etiology begins with an increase in body temperature, runny nose and cough. A cough may appear immediately, in the absence of breathing problems from the nasopharynx. The cough may be dry and hacking in the first days, and then become unproductive and wet. Some children have a wet cough from the first days, that is, they clear their throat well. Cough and fever can last on average 5-7 days. Depending on the age of the child and the type of virus that has entered the body, cough and fever can persist for up to 2 weeks.

For obstructive bronchitis

Sometimes bronchitis in a child occurs with signs of obstruction - this is a narrowing of the bronchi due to swelling of the mucous membrane, accumulation of viscous sputum in the bronchi and spasm of the muscles of the bronchi. It is often called obstructive bronchitis. Obstructive bronchitis is accompanied by prolongation of exhalation, which can occur as early as 1-2 days of illness. With obstructive bronchitis, the cough is unproductive and can sometimes be intrusive.

When infected with pulmonary chlamydia

With bronchitis caused by mycoplasma or pulmonary chlamydia, elevated body temperature can persist for up to 2 weeks, while the cough is not pronounced, but lasts a long time, up to 2-3 weeks.

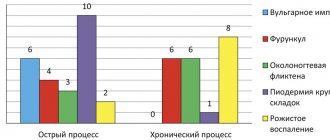

Causes of pathology

The main cause of obstructive bronchitis is infection.

The main microorganisms that cause the development of bronchospasm and swelling of their mucous membranes are not bacteria, but viruses (rhinoviruses, respiratory syncytial virus, adenoviruses). In children over three years of age, a special type of bacteria called intracellular parasites also takes the “leading” position: chlamydia, mycoplasma, ureaplasma. The non-infectious cause of the pathology – allergic – is also of great importance. Pathology can be caused by plant pollen, chemicals in the form of aerosols, medications, food products, animal saliva, household chemicals and perfumes. An important factor is smoking – passive or active.

Treatment of bronchitis

Treatment of bronchitis in children is carried out on the basis of clinical recommendations and standards. They summarize the experience of treating children and adolescents, taking into account data accumulated by foreign and Russian specialists.

In case of acute bronchitis, it is better to provide the child with semi-bed rest until the body temperature decreases. In this situation, the baby needs to be given more to drink during the day. If your child wakes up at night, it is better to offer him something to drink at night. It is important to ensure that the sick person has improved sputum discharge and to help the child cough up - this is a light vibration massage (tapping on the chest and breathing exercises, which are carried out in the morning, afternoon and evening. It is better to carry out these procedures on an empty stomach and in a playful way in order to set the sick child up for positivity and recovery .

The room where the sick child is located must have fresh, humidified air. Dry air will cause mucus to dry out, meaning the child will not be able to cough up effectively and efficiently and remove mucus from the bronchi. In this situation, it is necessary to regularly ventilate the room. Use a humidifier, which can sometimes work around the clock during illness. In winter, try to reduce the operation of radiators heating the room, as they make the air dry. If this is not possible, then cover the radiators with a damp cloth. We must try not to make the room hot. The best temperature is 22 degrees. For a child with bronchitis, in the absence of elevated body temperature and intoxication, walks in the fresh air with low physical activity are very useful.

If a child has a dry cough, then centrally acting cough medications can help him, but they are not used for long - 2-3 days.

Sometimes antiviral drugs can help a baby with bronchitis. They are prescribed if there was a viral infection (ARVI) at the onset of the disease.

For mucus that is difficult to clear, mucolytic drugs are prescribed - these are drugs that thin the sputum. Medicines are also prescribed to help move sputum from the lower sections of the bronchi to the upper ones - they enhance the movements of the cilia located in the bronchi. Therefore, sputum moves faster from the lower to the upper sections.

Treatment of obstructive bronchitis

In acute bronchitis with obstruction syndrome, it is advisable to prescribe bronchospasmolytic drugs, since the cause of the child’s serious condition is also a spasm of the smooth muscle layer.

In a situation of acute bronchitis with bronchial obstruction syndrome, inhalation procedures using special drugs are prescribed. It is necessary to choose the type of inhaler for a sick child with a doctor who, based on the clinical manifestations of this disease and the characteristics of your child’s body, will select the tactically correct route of inhalation therapy and dose. Antibacterial therapy, that is, the use of antibiotics in this case is not indicated. But if the baby’s temperature remains above 38° for more than 5 days, it is necessary to conduct a laboratory test and, possibly, take a chest x-ray. The results of these examinations will decide on further treatment and the use of antibiotics. The doctor will prescribe the necessary antibacterial drug based on the characteristics of the clinical manifestations of bronchitis in a given patient and the results of the examination.

Diagnostics

After examining the patient and collecting anamnesis, the specialist will prescribe additional tests, the results of which will help make the correct diagnosis.

Laboratory tests - general blood test, general urine test, sputum analysis.

Instrumental examination - radiography and spirometry.

It is very important to differentiate obstructive bronchitis from bronchial asthma

After carrying out diagnostic measures, the doctor will tell you how to treat chronic obstructive bronchitis and how to prevent the development of exacerbation. For this purpose, traditional medicine recipes can be used.

Prevention

In the modern situation, it is necessary to pay great attention to the prevention of bronchitis. Prevention in children is vaccination against various infections. It is important that not only the child is vaccinated, but that everyone around him is also vaccinated. A big role for children is played by hardening, fresh indoor air, adherence to a daily routine, constant physical education, active walks in the fresh air, proper and regular healthy nutrition appropriate for the child’s age, and the use of vitamins.

Causes of prolonged cough not related to bronchitis:

- sinusitis and postnasal drip syndrome (this is the flow of nasal mucus along the back wall of the pharynx into the respiratory tract). Most patients have mucous or mucopurulent nasal discharge.

- postnasal drip can occur with general cooling of the body, allergic and vasomotor rhinitis, irritating environmental factors;

- Various foreign bodies can enter the child’s bronchi - through swallowing, choking, inhalation;

- oncology, pleurisy - here the diagnosis will be correctly made when additional types of examination are carried out;

- a prolonged cough can be due to heart failure (in this situation, the cough often occurs at night when the child is sleeping); the diagnosis is helped by examination of the chest organs and echocardiography.

- a child may be allergic to various irritants (food, household or plant allergens, taking certain medications, the presence of some animals in the house).

- If a child has a prolonged cough, it is necessary to exclude the infectious disease whooping cough.