Impetigo

(lat.

impetigo

) - a contagious skin disease of streptococcal and staphylococcal etiology; one of the common forms of pyoderma (see). In the Middle Ages, impetigo was the name given to all skin lesions covered with purulent crusts. In the 18th century R. Villan and Th. Bateman refined the term impetigo, which came to be used to refer to diseases characterized by superficial pustules that quickly dry into yellow, loose crusts. Fox (W.T. Fox) clinically confirmed the contagious nature of Impetigo and proposed calling it impetigo contagiosa.

Impetigo

Impetigo is a bacterial disease of the superficial layers of the skin, manifested by specific vesiculopustular rashes.

As it progresses, it can cause serious complications and therefore requires prompt treatment. This is a contagious disease transmitted through household contact.

Impetigo is most often diagnosed in children. Children are constantly in close contact with each other, attending educational institutions, playing on playgrounds, etc., regularly exchanging toys and things - this contributes to the spread of infection. In addition, the children's body resists infections worse than the body of adults.

Prevention

Sanitation of the skin and oral cavity and the introduction of vitamins are important. In nurseries and kindergartens, systematic sanitary and epidemiological supervision and hardening of children are necessary; Careful monitoring of the skin condition of adolescents undergoing industrial training is very important. At production enterprises it is necessary to carry out sanitary hygiene. measures: protecting the skin from pollution and damage, timely treatment of micro-traumas, proper skin care.

Bibliography:

Belenky G. B. Pyodermatitis, p. 64, M., 1958; Borzov M.V. Pustular skin diseases, Chisinau, 1953; Golosovker S. Ya. Pyoderma in children, p. 49, 54, M., 1960; Brown GR Systemic therapy of impetigo, Clin. Med., v. 80, p. 36, 1973; David V. L'impetigo et son treatment, Rev. Med. (Paris), t. 11, p. 1635, 1970; El Zawahry M., Abdel Aziz A. a. Soliman M. The aetiology of impetigo contagiosa, Brit. J. Derm., v. 87, p. 420, 1972.

Yu. K. Skripkin.

Causes of skin impetigo

The causative agents of the disease are streptococci and staphylococci. These opportunistic bacteria are present in the air of unventilated rooms and can be present in the body of a healthy person. With strong immunity, they do not cause skin diseases, but under favorable conditions they contribute to the spread of infection. These conditions include:

- insufficient body hygiene;

- violation of skin protective mechanisms;

- presence of microtraumas, cracks, etc.;

- insect bites;

- decreased general or local immunity;

- excessive sweating;

- work in dusty rooms;

- chicken pox;

- scabies;

- herpes, etc.

Pathohistology

Both with streptococcal and staphylococcal varieties of I. the main element is the pustule, the edges develop directly under the stratum corneum. Pustule (see) contains fibrin, neutrophilic leukocytes and a certain amount of lymphocytes. In the pustule you can find groups of cocci located extracellularly or inside neutrophils. In the spinous layer under the pustule there is spongiosis (see), many migrating neutrophils. In the upper part of the dermis there is a slight inflammatory infiltrate consisting of neutrophils and lymphocytes.

Types and symptoms of impetigo

Depending on the type of pathogen, impetigo is divided into staphylococcal and streptococcal. A mixed form also occurs, when a patient has both infections at once.

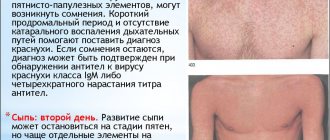

Staphylococcal impetigo belongs to the group of folliculitis, since it affects only the hair follicles. Multiple pustules form on the hairy areas of the body. They can reach 5 mm in diameter and have a pinkish border. With superficial impetigo, the pustules quickly dry out and become covered with a yellow crust, which after about 3 days separates from the skin on its own, leaving no traces. When the skin is deeply damaged, the ulcers are painful, reach the size of a pea, and leave scars after opening.

Streptococcal impetigo is characterized by the appearance on the skin of red macular-tubercular rashes, which turn into blisters with a diameter of 2–10 mm, surrounded by a thin rim of hyperemic skin. Initially they are filled with a clear liquid, but gradually the contents become cloudy. After opening, superficial erosions remain on the skin. They become covered with light yellow crusts, which fall off after a few days.

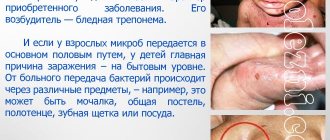

The streptococcal form of the disease has several types. A common type is slit impetigo. In everyday life this problem is called jams. First, a bubble filled with liquid appears in the corner of the mouth, which quickly becomes covered with a crust. If it is removed, a red bleeding crack will form. After an hour or two it becomes crusty again.

The most dangerous type of streptococcal infection is bullous impetigo. It is characterized by the appearance on the legs of large (up to 20 mm in diameter) blisters filled with bloody exudate mixed with pus. Once opened, rough crusts form. The disease occurs with increased body temperature and symptoms of intoxication.

Vulgar impetigo is diagnosed when streptococcal and staphylococcal infections are detected in the patient’s body at the same time. The rash usually occurs on the face, sometimes on the body. The blisters are filled with clear or purulent exudate. After opening, more massive wounds remain than with simple forms of pathology. Children and young women are especially susceptible to the disease.

Classification

There are several wedges, types of I. (according to etiology):

1. I. streptococcal, or streptogenic (syn.: Fox's impetigo, Jadassohn's impetigo, superficial streptoderma), including seven wedges, varieties: ring-shaped I., bullous I., slit-like I., I. vegetative, I. mucous membranes, syphiloid post-erosive papular I. and simple lichen of the face (syn. pityriasis alba).

2. I. staphylococcal, or staphylogenic (syn.: Bockhart’s impetigo, follicular I., superficial staphylococcal folliculitis).

3. I. streptostaphylococcal, or streptostaphylogenic (syn. vulgar I.).

The previously isolated pemphigoid form of streptococcal I. is the so-called. Pemphigus of newborns is classified as a disease of staphylococcal nature (see Pyoderma).

Diagnosis of impetigo

The dermatologist makes a preliminary conclusion when examining the patient, taking into account the clinical picture of the disease. To determine the pathogen, smear microscopy and bacteriological culture of the discharge from the vesicles are performed.

Additionally, dermatoscopy and a clinical blood test are prescribed.

Differential diagnosis of impetigo is carried out with herpes simplex, dyshidrosis, candidiasis, chickenpox, herpes simplex, dermatophytosis, contact dermatitis, pemphigus vulgaris, dermatitis herpetiformis, bullous scabies, erysipelas.

Treatment of impetigo

During therapy, damaged skin areas and adjacent areas are prohibited from getting wet. They should be wiped twice a day with an antiseptic, for example, an alcohol solution of salicylic acid.

After opening the blisters, the skin is lubricated with a brilliant green solution (“brilliant”) or fucorcin and antibacterial ointment, for example, Erythromycin, Levomycetin, Syntomycin, Fusiderm. The procedure is repeated 3-4 times a day until complete recovery; usually the course of therapy lasts no more than 10 days.

If external treatment does not produce the desired results, the disease is widespread or recurrent, systemic antibiotics for impetigo in oral or intramuscular dosage form are required. The doctor selects the drug, its dose and method of administration for a child or adult individually for each patient.

Links[edit]

- ^ a b c

"Impetigo - school ulcers".

Bettel Health Channel

. Archived from the original on July 5, 2021. Retrieved May 10, 2017. - ^ a b c d

Ibrahim , F;

Khan, T; Puhalte, G.G. (December 2015). "Bacterial skin infections." Primary care

.

42

(4): 485–99. DOI: 10.1016/j.pop.2015.08.001. PMID 26612370. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae

Hartman-Adams, H;

Banvard, C; Jackett, J. (2014, August 15). "Impetigo: diagnosis and treatment." American family physician

.

90

(4): 229–35. PMID 25250996. - ^ a b

Adams, B. B. (2002).

"Dermatological diseases of the athlete." Sports medicine

.

32

(5): 309–21. DOI: 10.2165/00007256-200232050-00003. PMID 11929358. S2CID 34948265. - ^ a b

Koning, S;

van der Sande, R; Verhagen, A.P.; van Suijlekom-Smit, L. W.; Morris, A.D.; Butler, S.S.; Berger, M; van der Wouden, J. C. (18 January 2012). "Interventions for impetigo". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

.

1

: CD003261. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003261.pub3. PMC 7025440. PMID 22258953. - ^ a b

Vos, T (December 15, 2012).

"Years lived with disability (YLD) due to 1160 consequences of 289 diseases and injuries, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet

.

380

(9859):2163–96. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMC 6350784. PMID 23245607. - "Impetigo symptoms and treatment". www.nhsinform.scot

. Retrieved May 26, 2021. - "Impetigo and ecthyma - skin diseases". Merck Consumer Guides

. Retrieved May 26, 2021. - Limited, Wordsworth editions (1993). Concise English Dictionary

. Wordsworth editions. item 452. ISBN. 9781840224979. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. - Cole S, Gazewood J (2007). "Diagnosis and treatment of impetigo". I am a family doctor

.

75

(6):859–64. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 17390597. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. - ^ a b c

Mayo Clinic Staff (October 5, 2010).

"Impetigo". Mayo Clinic Health Information

. Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on November 28, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2012. - ^ a b

Kumar, Vinay;

Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson; & Mitchell, Richard N. (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology

(8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. p. 843 ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1 - Stulberg DL, Penrod MA, Blatny RA (2002). "Common bacterial skin infections". American family physician

.

66

(1): 119–24. PMID 12126026. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. - "Impetigo (school sores)". www.health.govt.nz

. Ministry of Health . Retrieved September 14, 2021. - "Impetigo". Health line

. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved October 7 +2016. - Tamparo, Carol; Lewis, Marcia (2011). Diseases of the human body

. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis Company. p. 194. ISBN 9780803625051. - "ISDH: Impetigo". state.in.us

. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2014. - "Impetigo: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov

. Archived from the original on November 7, 2021. - "Self Management - Impetigo - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org

. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 7 +2016. - ^ a b c

Baddour, Larry.

"Impetigo". UpToDate

. Retrieved August 15, 2021. - Fleisher, Gary R.; Ludwig, Stephen (01/01/2010). Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine

. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. item 925. ISBN 9781605471594. Archived from the original on September 8, 2021. - "Impetigo: prescribing antimicrobials - NICE guideline [NG153]". www.nice.org.uk.

_ Retrieved May 26, 2021. - Mahaze, Elizabeth (15 August 2019). 'Doctors should treat impetigo with antiseptics rather than antibiotics, says NICE'. BMJ

.

366

: l5162. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.l5162. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 31416810. S2CID 201018620. - ^ a b

Bowen, Asha;

Mahe, Antoine; Hay, Roderick; Andrews, Ross; Steer, Andrew; Tong, Stephen; Karapetis, Jonathan (2015). "Global epidemiology of impetigo: a systematic review of population prevalence of impetigo and pyoderma". PLOS ONE

.

10

(8):e0136789. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1036789B. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136789. PMC 4552802. PMID 26317533. - ^ a b

Romani, Lucia;

Steer, Andrew; Whitfeld, Margot; Kaldor, John (2015). "Worldwide prevalence of scabies and impetigo: a systematic review." Lanceolate infectious diseases

.

15

(8): 960–7. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00132-2. PMID 26088526. - George, Ajay; Rubin, Greg (2003). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of impetigo treatment". British Journal of General Practice

.

53

(491): 480–7. PMC 1314624. PMID 12939895. - "Impetigo". British Medical Journal

.

1

(4185): 448. 1941. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4185.445-a. JSTOR 20319413. S2CID 214846855. - Barnhart's Concise Dictionary of Etymology

. Harper Collins. 1995. ISBN. 978-0-06-270084-1. - MacDonald RS (October 2004). "Cure for Impetigo: Paint It Blue". BMJ

.

329

(7472): 979. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.329.7472.979. PMC 524121. PMID 15499130.

Frequently asked questions about impetigo

How does impetigo manifest?

First, red spotty-tubercular rashes appear on the body, which soon turn into bubbles filled with cloudy liquid (the so-called phlyctenes). They are located scattered on different parts of the body or in groups. After opening, they are covered with a yellowish or golden crust. This symptom is specific to impetigo. To confirm the diagnosis, the doctor performs a bacteriological culture.

Why is impetigo dangerous?

Mild forms of the disease often resolve on their own - the blisters burst, become covered with a crust, which soon disappears. There are no scars left on the skin. But in severe cases of the disease, especially if it is caused by staphylococci, there is a risk of developing an abscess, phlegmon, and sepsis. In rare cases, complications from the kidneys and heart occur against the background of systemic infection.

How does impetigo appear in children?

The disease is transmitted through household contact from an infected person. Children actively communicate with each other, so they are more susceptible to infection.

Epidemiology[edit]

Globally, impetigo affects more than 162 million children in low- and middle-income countries. [24] These rates are highest in countries with limited available resources and are particularly common in the Oceania region. [24] Tropical climates and high populations in lower socioeconomic regions contribute to these high rates. [25] Children under 4 years of age in the United Kingdom are 2.8% more likely to develop impetigo; for children under 15 years of age this figure drops to 1.6%. [26] The incidence of impetigo decreases with age, but all ages are still susceptible to the condition. [25]