The ARVI season is in full swing, which means that in most pharmacies there is a stable demand for drugs for the symptoms of this type of disease. Cough is a symptom that haunts a person long after the end of the acute phase of an infectious disease. Let's refresh our knowledge about cough and the principles of choosing syrups - one of the most popular groups of drugs in the pharmacy. It is not surprising that the demand for syrups is invariably high: firstly, properly selected syrup helps well, secondly, many will prefer sweet syrup to swallowing “soulless” tablets, and thirdly, syrups are well suited for a children's first aid kit.

Coughing is a complex reflex act, which is normally aimed at clearing the airways. A cough can also occur due to pathological irritation of the vagus nerve receptors located in the mucous membrane of the larynx, vocal cords, tracheal bifurcation or at the divisions of large bronchi.

An important characteristic of a cough is its productivity. Conditions characterized by a dry cough (non-productive) and a wet cough (productive) are presented in Table No. 1.

Warning signs

Cough can be a symptom of non-inflammatory and non-infectious diseases, so prolonged cough in young patients that does not respond to conventional treatment and prolonged cough in elderly patients are important indications for a thorough medical examination. In this case, it is first of all important not to miss tumor and lymphoproliferative diseases. Such a pharmacy client should be advised to urgently visit a doctor. In childhood, a barking cough caused by swelling of the larynx cannot be cured with syrups either; we send such clients to a pediatrician.

The variety of types of cough syrups often confuses pharmacy visitors. In the absence of a doctor's prescription, the primary care provider must help the client make the right choice among over-the-counter syrups. Prescription drugs include all bronchodilators and antitussives that inhibit the cough reflex. Thus, you will have to choose among expectorant syrups that enhance or facilitate the separation of bronchial mucus (sputum) when coughing. Mucolytic cough syrups facilitate the production of sputum, and secretory syrups increase its secretion. Thus, the former are used for wet coughs, and the latter for dry coughs.

Types of syrups

Here you can download the reference table in PDF format, print it and keep it with you at all times. It is devoted to three types of OTC cough syrups: secretory, mucolytic and combined action. The table will help you choose a drug based on its composition, indications and contraindications.

Link to table

Mucolytics include all syrups containing acetylcysteine, carbocysteine, ambroxol and bromhexine. These drugs have almost no age restrictions. Mucolytic syrup will not help with a dry cough, that is, when the sputum does not come out at all. Combined expectorant mucolytics often contain medicinal herbs. Their common contraindications are hypersensitivity to one of the components, as well as children's age, often under 6 years.

Table 1. Examples of conditions causing dry and wet cough

| Dry cough | Cough wet |

| Initial phase of acute laryngitis, bronchitis, pneumonia Pre- and attack periods of bronchial asthma Catarrhal period whooping cough Foreign body Disseminated forms of tuberculosis Compression of the respiratory tract by enlarged lymph nodes, tumor Pleurisy Gastroesophageal reflux disease Taking ACE inhibitors | Chronic bronchopulmonary inflammatory processes Pneumonia Acute simple and obstructive bronchitis Attack (after improvement of bronchial patency) and post-attack periods of bronchial asthma Spastic period of whooping cough Cystic fibrosis Lung abscess Pulmonary tuberculosis Malformations of the trachea and bronchi Parasitic lesions of the lungs |

Acetylcysteine is a derivative of the amino acid cysteine. The sulfide groups of this substance break the disulfide bonds of sputum proteoglycans, leading to their depolymerization, which reduces the viscosity and adhesiveness of sputum. It also has some secretolytic effect - it increases the volume of sputum.

Carbocysteine - in chemical formula and severity of action is similar to acetylcysteine. Syrups with this active ingredient also change the rheological properties of sputum, diluting it, which facilitates discharge, but these drugs do not have a secretolytic effect.

Ambroxol, thanks to many manufacturers and many forms of the drug, is one of the most popular mucolytics today. Its mucolytic effect is due to a change in the structure of sputum mucopolysaccharides and an increase in the secretion of glycoproteins. It also increases the activity of the ciliated epithelium. The effect after oral administration develops within 30 minutes and lasts 10–12 hours. The instructions often indicate restrictions for use in childhood.

Bromhexine is also one of the most popular mucolytics. In the body, the metabolism of bromhexine leads to the formation of ambroxol. The drug is well tolerated, but is contraindicated in cases of hypersensitivity, peptic ulcer disease (in the acute stage), pregnancy (especially the first trimester), breastfeeding, and children under 3 years of age.

Secretomotor cough syrups (secretolytics) are necessary for dry coughs; these are mainly expectorant herbal syrups containing extracts of licorice and marshmallow. Having an irritating effect on the receptors of the gastric mucosa, they increase the secretion of the bronchial glands and the mobility of the ciliated epithelium. The result of this is an increase in the volume of sputum, it becomes liquid, less viscous and adhesive.

Licorice root contains many substances that, in addition to secretolytic, also have anti-inflammatory and antispasmodic effects. The syrup has no age restrictions, but it should be used with caution both in childhood and during exacerbation of bronchial asthma.

Marshmallow root - in addition to being an expectorant, has a less pronounced anti-inflammatory effect. The only contraindication to its use is hypersensitivity, but, like many other drugs, it should be used with caution in bronchial asthma and in childhood.

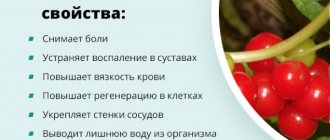

Cough syrups often contain common thyme or creeping thyme (thyme). Thyme herb contains essential oil (up to 1%), tannins, bitter and coloring substances, as well as flavonoids, vitamin C and mineral salts. Cough syrups with thyme herb extract have an anti-inflammatory effect, as well as expectorant and analgesic properties.

An integrated approach to the treatment of cough: a duo of herbal preparations Eucabal® syrup for oral administration and Eucabal® Balsam C for external use will help cope with both dry and wet coughs in children and adults.

Eucabal® cough syrup contains extracts of thyme (thyme) and plantain. It has a pronounced expectorant and anti-inflammatory effect, protecting the mucous membrane from irritation that causes coughing. Oils of pine needles and eucalyptus leaves, which are part of Eucabal® Balsam C, support the effect of the syrup. By activating blood circulation and relieving spasms in the respiratory organs, it also has a pronounced expectorant and anti-inflammatory effect.

THERE ARE CONTRAINDICATIONS. YOU SHOULD CONSULT WITH A SPECIALIST.

Treatment of acute respiratory diseases in children

Acute respiratory diseases (ARI) are a large group of infections that have much in common in pathogenesis and transmission routes: we are talking mainly about airborne infections, although contact (through dirty hands) transmission route plays an equally important role. This term is used to combine acute nonspecific infections, regardless of their location - from rhinitis to pneumonia. However, as a clinical diagnosis of acute respiratory infections, it requires deciphering: there must be an indication of either organ damage (otitis media, bronchitis, pharyngitis, etc.), for which the spectrum of pathogens is known, or the possible etiology of the disease (viral, bacterial acute respiratory infections). Since up to 90% of acute respiratory infections are caused by respiratory viruses and influenza viruses, in the absence of signs of bacterial infection, the term “acute respiratory viral infection” (ARVI) and the prescription of antiviral therapy are justified.

According to the authors of a series of works carried out under the auspices of WHO, in different countries - both developed and developing - young children suffer 5-8 acute respiratory infections annually, and in rural areas they get sick less often than in cities, where a child can suffer 10- 12 infections per year. Children, who in early childhood have less contact with sources of infection and therefore get sick less during this period, “get the missing infections” in primary school. Statement of this fact, of course, should not be the reason for the development of fatalism regarding ARVI - children should be hardened and, if possible, protected from sources of infection, adequately fed and treated for diseases (chronic tonsillitis, allergies), against the background of which ARVI develops especially often. At the same time, it is necessary to protect sick children in every possible way from unnecessary therapeutic interventions, since acute respiratory infections are the reason for unnecessary treatment and the most common cause of side effects of drugs.

Antiviral agents

Strictly speaking, antiviral therapy is indicated for any respiratory viral disease. Unfortunately, the antiviral drugs at our disposal often do not provide a pronounced effect, and the mildness of most episodes of ARVI, limited to 1-3 feverish days and catarrhal syndrome for 1-2 weeks, does not justify chemotherapy. But in more severe cases, especially with influenza, antiviral drugs have a certain effect and should be used more widely than is considered appropriate today.

The basic rule for the use of antiviral chemotherapy drugs is their administration in the first 24–36 hours of illness; at a later date, their effect is not visible. The main anti-influenza drug, which also acts on a number of other viruses [1], is rimantadine, which suppresses the reproduction of all strains of influenza type A. Rimantadine also inhibits the reproduction of respiratory syncytial (RS) and parainfluenza viruses. Recommended; 5-day course at the rate of 1.5 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses for children 3–7 years old; 50 mg 2 times for children 7–10 years old - 3 times a day - over 10 years old [2]. At an early age, rimantadine is used in the form of algirem (0.2% syrup): in children 1–3 years old, 10 ml; 3-7 years - 15 ml: 1st day 3 times, 2nd-3rd days - 2 times, 4th - 1 time a day. The effectiveness of rimantadine increases when taken with the drug no-shpa (drotaverine) orally, at a dose of 0.02–0.04 g for children 4–6 years old and 0.04–0.1 g for patients 7–12 years old. especially when heat transfer is impaired (cold extremities, marbling of the skin) [3].

Arbidol has a similar antiviral effect, inhibiting the fusion of the lipid membrane of influenza viruses with the membrane of epithelial cells. It is also an interferon inducer. This low-toxic drug can also be prescribed for moderate ARVI from the age of 2: for children 2–6 years old, 50 mg per dose, 6–12 years old, 100 mg, over 12 years old, 200 mg per dose 4 times a day. Both rimantadine and arbidol reduce the febrile period by an average of 1 day in both influenza A2, mixed infections, and non-influenza ARVI [1].

Ribavirin (ribamidil, virazole) is an antiviral drug originally used (mainly in the USA) as having activity against the RS virus in bronchiolitis in the most severely ill patients with an unfavorable premorbid background (premature infants, with bronchopulmonary dysplasia). The drug is used for this purpose in the form of continuous (up to 18 hours a day) inhalations through a special inhaler at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day; Due to the high price and side effects, it is practically not used in Europe. It also turned out that this drug is active against influenza viruses, parainfluenza, herpes simplex, adenoviruses, as well as coronavirus, the causative agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). For influenza in adolescents over 12 years of age, it is used orally at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day for 5–7 days. For SARS, ribavirin is administered intravenously.

Progress in the treatment of influenza caused by both type A and type B viruses may be due to the use of the neuraminidase inhibitors oseltamivir-Tamiflu and zanamivir-Relenza. These drugs, when taken early, reduce the duration of fever by 24–36 hours and have a preventive effect, but there is little experience in their use in children (from 12 years of age) in Russia, and in recent years there is practically no mention of them in reference books. Relenza is used in the form of powder inhalations (in the USA from 7 years of age) - 2 inhalations (5 mg each) per day with an interval of at least 2 hours (on the 1st day) and 12 hours (from the 2nd to the 5th day treatment). Tamiflu (75 mg capsules and 12 mg/ml suspension) in adults and children over 12 years old is used at 75 mg once a day for 5 days (in the USA, doses for children 1–12 years old: weighing up to 15 kg - 30 mg 2 times a day, 15-23 kg - 45 mg 2 times a day, 23-40 kg - 60 mg 2 times a day). This drug is the only one to which H5N1 avian influenza is sensitive, and a number of countries are currently stockpiling it in case of an epidemic, which apparently limits its use with relatively small production (Hoffman-La Roche, Switzerland, produces 7 million doses of Tamiflu in year).

The drugs Florenal 0.5%, oxolinic ointment 1–2%, bonafton, lokferon and others used locally (in the nose, in the eyes) have some antiviral activity; they are indicated, for example, for adenovirus infection. Although their effect is difficult to assess, the low toxicity justifies the use of these agents.

Proteolytic processes occurring during the synthesis of viral polypeptides, as well as the fusion of viruses with cell membranes, can inhibit aprotinins - contrical, gordox, etc., as well as amben. These drugs can be used for severe forms of respiratory infections with high inflammatory activity, usually with signs of disseminated intravascular coagulation (as fibrinolysis inhibitors) and microcirculatory disorders. Ambien is part of hemostatic sponges. Contrical is used at a dose of 500–1000 IU/kg/day. Olifen and Erisod, used in adults and included in this group of drugs, have not yet been tested in children.

Interferons and their inducers have universal antiviral properties, suppressing the replication of both RNA and DNA, while simultaneously stimulating the immunological reactions of the macroorganism. Early use of interferons can, if not interrupt the course of the infection, then mitigate its manifestations.

Native leukocyte interferon α (1000 IU/ml - 4-6 times a day in the nose in a total dose of 2 ml on the 1st-2nd day of illness) is less effective than recombinant interferon preparations [4]. Among the latter, the use of influenza feron - interferon α-2β (10,000 IU/ml) with thickeners is promising; it is administered in the form of drops in the nose - 5 days, for children under one year old - 1 drop 5 times a day (single dose 1000 IU, daily dose - 5000 IU), for children from 1 to 3 years old 2 drops 3-4 times a day (single dose 2000 IU, daily dose - 6000-8000 IU), from 3 to 14 years - two drops 4-5 times a day (single dose - 2000 IU, daily dose - 8000-10 000 IU). The administration of interferon drugs parenterally, practiced, for example, for the treatment of chronic hepatitis, is hardly justified in the vast majority of respiratory infections. However, a number of studies have shown the effectiveness of rectal suppositories Viferon - interferon α-2β + vitamins E and C for influenza and ARVI. Viferon-1 (150,000 IU) is used in children under 6 years of age, Viferon-2 (500,000 IU) in children older 7 years - they are prescribed 2-3 times a day for 5 days. Viferon is also used prophylactically in frequently ill children [3].

Laferon - interferon α-2β powder - is used in the form of nasal drops, and in children over 12 years of age it is administered intramuscularly at a dose of 1-3 million IU.

In addition to arbidol, a number of drugs are used as interferon inducers. Amiksin (Tilorone) has gained the most popularity among children over 7 years of age - it is administered at the first symptoms of acute respiratory infections or flu orally after meals, 60 mg 1 time per day on the 1st, 2nd, and 4th day from the start of treatment. Children's anaferon - homeopathic doses of affinity-purified antibodies to interferon α, it is used 1 tablet every 30 minutes for 2 hours, then 3 times a day, but there is little convincing data on its effectiveness so far.

In children with ARVI, it is often necessary to treat a primary herpesvirus infection that occurs as severe febrile stomatitis. Children with atopic dermatitis often develop Kaposi's eczema, a herpesvirus infection of the affected skin that is also severe. In older children, ARVI is the most common cause of reactivation of herpes viruses in the form of specific rashes on the lips, wings of the nose, and less often on the genitals. This infection responds well to treatment with acyclovir - it is used at a dose of 20 mg/kg/day in 4 doses, in severe cases - up to 80 mg/kg/day or intravenously at 30-60 mg/kg/day. Valacyclovir does not require divided administration; its dose for adults and adolescents over 12 years of age is 500 mg 2 times a day.

For the treatment of acute respiratory viral infections, a significantly larger number of drugs are used in practice, including those of plant origin (adaptogens, dietary supplements, tinctures, etc.). There is no data on the effectiveness of the vast majority of them, but side effects are often encountered.

Antibacterial agents

Bacterial acute respiratory infections in children, as in adults, are relatively few in number, but they pose the greatest threat in terms of the development of serious complications. Making a diagnosis of bacterial acute respiratory infections at the bedside of an acutely ill child is very difficult due to the similarity of many of their manifestations with those of acute respiratory viral infections (fever, runny nose, cough, sore throat), and rapid methods of etiological diagnosis are practically unavailable. And the identification of a microbial pathogen in the material of the respiratory tract does not indicate its etiological role, since most bacterial diseases are caused by pathogens that constantly grow in the respiratory tract.

Under these conditions, naturally, the doctor, at the first contact with the child, tends to overestimate the possible role of the bacterial flora and use antibiotics more often than necessary. Our data show that in Moscow antibiotics are prescribed to 25% of children with ARVI; in some Russian cities this figure reaches 50–60%. The same trend is typical for other countries: antibiotics for ARVI are used in children in 14–80% of cases [6, 7]. Indicators close to our data are given by authors from France (24% [8]) and the USA (25% [9]). In developing countries, antibacterial drugs for acute respiratory infections are also used too widely, although this process is constrained by their lower availability. In China, 97% of children with acute respiratory infections who seek medical help receive antibiotics [10]. It is obvious that with a viral etiology of the disease, antibiotics are at least useless and, most likely, even harmful, since they disrupt the biocenosis of the respiratory tract and thereby contribute to the colonization of them by unusual, often intestinal, flora [11].

Antibiotics in children with ARVI more often than in bacterial diseases cause side effects - various rashes and other allergic manifestations. During bacterial processes in the body, a powerful release of a number of mediators (for example, cyclic adenosine monophosphate) occurs, which prevent the manifestation of allergic manifestations. This does not happen with viral infections, so allergic reactions occur much more often.

Another danger of excessive use of antibiotics is the spread of drug-resistant strains of pneumotropic bacteria, which is observed in many countries around the world. It is obvious that the unjustified use of antibiotics also leads to unnecessary treatment costs.

The effect of antibiotics on the development of the child’s immune system should not be ignored. The predominance of the immune T-helper response type 2 (Th-2), characteristic of a newborn, is inferior to the more mature T-helper response type 1 (Th-1), largely under the influence of stimulation by endotoxins and other products of bacterial origin. Such stimulation occurs both during a bacterial infection and during an acute respiratory viral infection, since a viral infection is accompanied by increased (albeit non-invasive) proliferation of pneumotropic flora [11]. Naturally, the use of antibiotics weakens or even suppresses this stimulation, which, in turn, contributes to the preservation of the Th-2 direction of the immune response, which increases the risk of allergic manifestations and reduces the intensity of anti-infective protection.

Indications for antibacterial treatment of acute respiratory infections

Recommendations from professional pediatric societies in most countries emphasize the importance of not using antibacterial agents in children with uncomplicated respiratory viral infection. The recommendations of the US Academy of Pediatrics emphasize that antibiotics are not used not only for uncomplicated ARVI, but also mucopurulent runny nose is also not an indication for the prescription of antibiotics if it lasts less than 10–14 days [8]. The French consensus allows the use of antibiotics for ARVI only in children with a history of recurrent otitis media, in infants under 6 months of age, if they attend a nursery, and in the presence of immunodeficiency [9].

The recommendations of the Union of Pediatricians of Russia indicate that for uncomplicated ARVI, systemic antibiotics are not indicated in the vast majority of cases [4]. This document lists symptoms observed in the first 10–14 days that do not justify the administration of antibiotics.

The question of prescribing antibiotics in a child with ARVI arises if he has a history of recurrent otitis media, an unfavorable premorbid background (severe malnutrition, congenital malformations) or if there are clinical signs of immunodeficiency.

The following are signs of a bacterial infection that require antibacterial treatment:

- purulent processes (sinusitis with swelling of the face or orbit, lymphadenitis with fluctuation, paratonsillar abscess, descending laryngotracheitis);

- acute tonsillitis with culture of group A streptococcus;

- anaerobic sore throat - usually ulcerative, with a putrid odor;

- acute otitis media, confirmed by otoscopy or with suppuration;

- sinusitis - if clinical and radiological changes in the sinuses persist 10–14 days after the onset of acute respiratory viral infection;

- respiratory mycoplasmosis and chlamydia;

- pneumonia.

More often than these obvious lesions, the pediatrician sees only indirect symptoms of a probable bacterial infection, among which the most common are persistent (3 days or more) febrile temperature, shortness of breath in the absence of obstruction (respiratory rate above 60 per 1 min in children 0–2 months of age , more than 50 per 1 minute at the age of 3–12 months and more than 40 in children 1–3 years old), asymmetry of auscultatory data in the lungs. Such symptoms force one to prescribe an antibiotic, which, if the diagnosis is not confirmed during subsequent examination, should be immediately discontinued.

For initial treatment of bacterial acute respiratory infections, a small set of antibiotics is used. For otitis and sinusitis, amoxicillin 45–90 mg/kg/day is prescribed orally to suppress the main pathogens - pneumococcus and Haemophilus influenzae. In children who have recently received antibiotics, amoxicillin/clavulanate 45 mg/kg/day is used, which suppresses the growth of probably resistant Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella in these patients.

Acute tonsillitis requires differential diagnosis between adenoviral tonsillitis, infectious mononucleosis and streptococcal tonsillitis. Viral tonsillitis is characterized by cough and catarrhal syndrome, streptococcal tonsillitis is characterized by absence of cough, and mononucleosis is characterized by blood changes. Antibiotics (penicillin vau, cephalexin, cefadroxil) are indicated for streptococcal tonsillitis; the use of amoxicillin is undesirable, since in mononucleosis it can cause toxic rashes. Although adenoviral tonsillitis does not require antibiotics, the presence of severe leukocytosis (15–25x109/l) and increased levels of C-reactive protein justify their use in many cases.

Bronchitis is usually a viral disease that does not require antibacterial treatment. The exception is bronchitis caused by mycoplasma; when they are detected, the use of macrolides (azithromycin, midecamycin, etc.) is indicated. Clinical signs of mycoplasma bronchitis are:

- age (preschool and older);

- high temperature without severe toxicosis;

- an abundance of crepitating wheezing (as with bronchiolitis in infants);

- asymmetry of wheezing;

- mild “dry” catarrh of the upper respiratory tract;

- hyperemia of the conjunctiva (“dry conjunctivitis”);

- local enhancement of the bronchovascular pattern on the radiograph.

The choice of antibacterial agents for the initial treatment of community-acquired pneumonia is also not very large, since most of the “typical” pneumonias are caused by pneumococcus or Haemophilus influenzae (with the exception of the first months of life, when the causative agent can be staphylococci and intestinal flora), while “atypical” forms are treatable macrolides. The choice of starting antibiotic for pneumonia is determined taking into account the likely causative agent of the disease.

For typical pneumonia (febrile, with a focus or homogeneous infiltrate), the following is used:

- 1–6 months (the most likely pathogens are E. coli, staphylococcus) - amoxicillin/clavulanate orally, intravenously; cefuroxime, ceftriaxone or cefazolin + aminoglycoside intravenously, intramuscularly;

- 6 months–18 years: mild (the most likely pathogens are pneumococcus, H. influenzae) — amoxicillin orally; severe (the most likely pathogens are pneumococcus, in children under 5 years old - H. influenzae type b) - cefuroxime, ceftriaxone or cefazolin + aminoglycoside intravenously, intramuscularly.

For atypical (with inhomogeneous infiltrate) pneumonia:

- 1–6 months (the most likely pathogens are C. trachomatis, U. urealyticum, rarely P. carinii) - macrolide, oral azithromycin, co-trimoxazole;

- 6 months–15 years (the most likely pathogens are M. pneumoniae, C. pneumoniae) — macrolide, azithromycin, doxycycline (> 12 years) orally.

Pathogenetic methods of treatment

These methods include interventions used for acute laryngitis and obstructive forms of bronchitis.

Acute laryngitis and croup are conditions that require assessment of the degree of stenosis, as judged by the intensity of inspiratory retractions of the chest, pulse and respiration rates. Grade 3 croup requires emergency intubation, grade 1 and 2 croup is treated conservatively. Antibiotics are not administered to a patient with laryngitis; according to global consensus, intramuscular dexamethasone 0.6 mg/kg is most effective, which stops the progression of stenosis. Further treatment is continued with inhaled steroids (dosed or through a nebulizer - Pulmicort) in combination with antispasmodics (salbutamol, Berotec, Berodual in inhalations).

Laryngeal stenosis can be caused by epiglottitis (H. influenzae type b plays a major role in its etiology) - it is characterized by high temperature and increased stenosis in the supine position; Prescribing an antibiotic (cefuroxime, ceftriaxone) in this case is mandatory.

Difficulty breathing and expiratory shortness of breath are often observed with bronchiolitis and obstructive bronchitis, as well as with an asthma attack against the background of ARVI. Since bacterial infection is rare in such cases, antibiotics are not justified. Treatment - inhaled sympathomimetics (in young children it is better in combination with ipratropium bromide) and the use of steroids in refractory cases - makes it possible to cope with obstruction in 1-3 days.

Symptomatic treatment of acute respiratory infections

As stated above, acute respiratory infections are the most common reason for the use of drugs, in particular symptomatic drugs, which occupy most of the pharmacy shelves. It is important, however, to clearly understand that the mere presence of a particular symptom should not be the basis for intervention; one must first of all assess the extent to which this symptom interferes with life and whether the treatment will be more dangerous than the symptom.

Fever accompanies most acute respiratory infections and is a protective reaction, so reducing its level with antipyretics is justified only in certain situations. Unfortunately, many parents and doctors consider fever the most dangerous manifestation of the disease and strive to normalize the temperature at all costs. According to our research [12], 95% of children with ARVI, including 92% of children with low-grade fever, receive antipyretics. This tactic cannot be considered rational, since fever, as a component of the body’s inflammatory response to infection, is largely protective in nature.

Antipyretics do not affect the cause of fever and do not shorten its duration; they increase the period of viral shedding in acute respiratory infections [12, 13]. With most infections, the maximum temperature rarely exceeds 39.5°. This temperature does not pose any threat to a child older than 2–3 months; Usually, in order to feel better, it is enough to lower it by 1–1.5°. Indications for reducing temperature [4]:

- For previously healthy children over 3 months of age - at a temperature > 39.0°–39.5°, and/or with discomfort, muscle aches and headaches.

- Children with a history of febrile seizures, severe heart and lung diseases, and from 0 to 3 months of life - with a temperature > 38°–38.5°.

The safest antipyretic for children is paracetamol, its single dose is 15 mg/kg, daily dose is 60 mg/kg. Ibuprofen (5–10 mg/kg per dose) more often produces side effects (with a similar antipyretic effect); it is recommended for use in cases where an anti-inflammatory effect is required (arthralgia, muscle pain, etc.).

For acute respiratory infections in children, acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) is not used - due to the development of Reye's syndrome, metamizole sodium (analgin) orally (danger of agranulocytosis and collaptoid state), amidopyrine, antipyrine, phenacetin. Nimesulide is hepatotoxic; unfortunately, its childhood forms have been registered in Russia, although they are not used anywhere else in the world.

Treatment of a runny nose with vasoconstrictor drops improves nasal breathing only in the first 1–2 days of illness; with longer use, they can worsen a runny nose and also cause side effects. At an early age, due to pain, only 0.01% and 0.025% solutions are used. Convenient (after 6 years) nasal sprays, which allow the drug to be evenly distributed at a lower dose (dlyanos, vibrocil). But the most effective way to cleanse the nose and nasopharynx, especially with thick exudate, is saline solution (or its analogues, including a solution of table salt prepared at home: add salt to 1/2 cup of water on the tip of a knife) - 2-3 pipettes in each nostril 3-4 times a day, lying on your back with your head hanging down and back. Orally administered remedies for the common cold containing sympathomimetics (phenylephrine, phenylpropanolamine, pseudoephedrine) are used after 12 years of age; from 6 years of age, Fervex for children, which does not contain these components, is prescribed. Antihistamines, including second generation, effective for allergic rhinitis, are not recommended by WHO for use in acute respiratory infections [15].

The indication for prescribing antitussives (non-narcotic centrally acting drugs - glaucine, butamirate, oxeladin) is only a dry cough, which usually quickly becomes wet in case of bronchitis. Expectorants (their cough-stimulating effect is similar to an emetic) are of questionable effectiveness and can cause vomiting in young children, as well as allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis. Their purpose is more a tribute to tradition than a necessity; expensive remedies from this group have no advantages over conventional herbal remedies; WHO generally recommends limiting oneself to “home remedies” [15].

Among the mucolytics, acetylcysteine is the most active, but in acute bronchitis in children there is practically no need for its use; carbocisteine is prescribed for bronchitis - based on its beneficial effect on mucociliary clearance. Ambroxol for thick sputum is used both orally and inhalations. Aerosol inhalations of mucolytics are used for chronic bronchitis; Aerosol inhalations of water, saline, etc. are not indicated for acute respiratory infections.

For long-lasting cough (whooping cough, persistent tracheitis), anti-inflammatory drugs are indicated: inhaled steroids, fenspiride (erespal). Emollient lozenges and sprays for pharyngitis usually contain antiseptics and are used from 6 years of age; starting from 30 months, a local antibiotic, fusafyungin, is used, produced in an aerosol (bioparox) and used both nasally and orally.

Mustard plasters, cups, and burning patches, which are still popular in Russia for bronchitis, should not be used in children; In case of acute respiratory infections, there are rarely indications for physiotherapy. Surprising is the popularity of halochambers, the purpose of which is to “inhale table salt vapors,” as in a salt mine. But in a salt mine, the patient is not exposed to salt (which is not a volatile substance), but to clean air, free of dust and other allergens; In addition, they are not there for 15 minutes. Treatment in a halochamber is not included in the consensus on asthma, however, many clinics spend a lot of money on their construction.

The means indicated in this section, with a few exceptions, cannot be considered mandatory for ARVI; Moreover, we often encounter side effects resulting from such treatment. Therefore, one should make it a rule to minimize drug loads in cases of mild ARVI.

The problem of acute respiratory infections in childhood remains relevant not only because of their prevalence, but also due to the need to revise and optimize treatment tactics. Accumulated data show that the approaches prevailing in pediatric practice at least do not contribute to the development of the child’s immune system, therefore, a revision of tactics should be primarily aimed at modifying therapeutic activity, in particular at reducing cases of unjustified prescriptions of antibacterial and antipyretic drugs.

Literature

- Drinevsky V.P. Assessment of the safety and effectiveness of new drugs for etiotropic treatment and specific prevention of influenza in children. M., 1999.

- Drinevsky V.P., Osidak L.V., Natsina V.K. et al. Chemotherapy in the treatment of influenza and other acute respiratory viral infections in children // Antibiotics and chemotherapy. M., 1998. T. 43. Issue. 9. pp. 29–34.

- Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Research Institute of Influenza. Standardized principles for diagnosis, treatment and emergency prevention of influenza and other acute respiratory infections in children. St. Petersburg, 2004.

- Union of Pediatricians of Russia, International Foundation for Mother and Child Health: Scientific and practical program “Acute respiratory diseases in children. Treatment and prevention." M., 2002.

- Mainous A., Hueston W., Love M. Antibiotics for colds in children: who are the high prescribers? Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1998; 52:349–352.

- Pennie R. Prospective study of antibiotic prescribing for children. Can. Fam. Physician 1998; 44: 1850–1855.

- Nyquist A., Gonzales R., Steiner GF, Sande MA Antibiotic prescribing for children with colds, upper respiratory infections, and bronchitis. JAMA 1998; 279:875–879.

- Chalumeneau M., Salannave B., Assathiany R. et al. Connaissance et application par des pediatres de ville de la conference de concensus sur les rhinopharyngites aigues de l'enfant. Arch. Pediatr. 2000; 7(5), 481–488.

- Jacobs RF Judicious use of antibiotics for common pediatric respiratory infections. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2000; 19(9):938–943.

- Li Hui, Xiao–Song Li, Xian–Jia Zeng et al. Pattern and determinants of use of antibiotics for acute respiratory tract infections in children in China. Pediatr. Infect. Dis J. 1997; 16 (6): 560RZR–564.

- Acute pneumonia in children/Ed. V. K. Tatochenko. Cheboksary: Publishing house. Chuvash University, 1994.

- Shokhtobov H. Optimization of the management of patients with acute respiratory infections in the pediatric area: Dis. ...cand. honey. Sci. M., 1990. 130 p.

- Romanenko A.I. Course and outcomes of acute respiratory diseases in children: Abstract of thesis. dis. ...cand. honey. Sci. M., 1988.

- Stanley ED, Jackson GG, Panusarn C. et al. Increased virus shedding with aspirin treatment of rhinovirus infection. JAMA 1975; 231:1248.

- World Health Organization. Cough and cold remedies for the treatment of acute respiratory infections in young children. WHO/FCH/CAH/01.02. WHO. 2001.

V. K. Tatochenko , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor of the Scientific Center for Children's Diseases of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Moscow