Specialization: endocrinology

L. P. Sleptsova, endocrinologist of the highest category, OXY-center infertility clinic, Krasnodar

Vaginal atrophy is a symptom of postmenopause, characterized by an estrogen deficiency state in women. The urogenital tract is especially sensitive to decreased estrogen levels. 27–55% of all postmenopausal women experience symptoms associated with urogenital atrophy (UGA), affecting sexual function and quality of life.

The clinical picture of urogenital disorders in the menopausal period includes symptoms associated with vaginal atrophy, as well as urination disorders (cystourethral atrophy). If vasomotor symptoms resolve over time, signs of vaginal atrophy progress. 40–57% of women experience vaginal dryness, burning and itching, dyspareunia, bleeding, urinary incontinence, and pelvic infections.

The walls of the vagina consist of three layers: internal, middle muscular and external connective tissue. Atrophic processes involve muscle and connective tissue structures, as well as the muscles of the pelvic floor, urethra, and bladder. They are especially pronounced in the vaginal mucosa, which consists of 4 main layers of epithelial cells: basal, parabasal (mitotically active), intermediate glycogen-containing and superficial exfoliating. Estrogen receptors are mainly located in the basal and parabasal layers and are practically absent in the intermediate and superficial layers. Estrogen deficiency blocks the mitotic activity of the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium and the proliferation of the vaginal epithelium. The consequence of the cessation of proliferative processes is the disappearance of glycogen - a nutrient medium for lactobacilli, and the complete elimination of lactobacilli, which play a key role in the prevention of diseases of the urogenital tract. Due to the breakdown of glycogen, provided there is a sufficient amount of estrogen, lactic acid is formed, providing an acidic environment within the range of pH fluctuations from 3.8 to 4.4. A similar mechanism leads to suppression of the growth of pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria. During the postmenopausal period, the mucous membrane loses its protective properties, becomes thinner, and is easily injured with subsequent infection.

Atrophy of the mucous membrane of the vulva and vagina is characterized by thinning, a decrease in vaginal folding, pallor, the presence of petechial hemorrhages, signs of inflammation, and also a loss of tissue elasticity, subcutaneous fat, loss of pubic hair, and a decrease in the secretory activity of the Bartholin glands. Typically, doctors diagnose vaginal atrophy based on a combination of clinical symptoms, visual examination, and the patient's subjective complaints.

To diagnose and evaluate the effectiveness of treatment of vaginal atrophy, it is necessary: pH and calculation of the vaginal maturation index (VII, predominance of cells of the basal and parabasal layers), a multisteroid blood profile.

1.General information

Vulvovaginal dystrophy (VVA) is a process of age-related histomorphological degeneration of the tissues of the vagina and genitals, as a result of which these parts of the female reproductive system gradually lose their natural properties and functions: they dry out, shrink in size, change in proportions, etc.

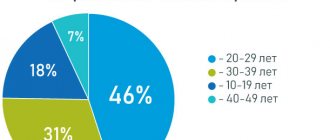

Large-scale events were carried out repeatedly, incl. international, surveys and research on this problem. The results indicate that VVA to varying degrees (as a clinically formed syndrome or as individual manifestations) is common with a frequency of 45-60% among postmenopausal women.

Almost all respondents note in this regard a significant decrease in the quality of life, especially in the psychosexual sphere, family relationships, self-esteem, and the area of subjective physiological comfort. At the same time, up to 80% of women are embarrassed, consider it unnecessary or useless to discuss the problem with their gynecologist; less than 40% have sufficient information about the essence of the changes taking place.

Thus, the problem of vulvovaginal dystrophy is acute and relevant even in the most developed countries of the world.

A must read! Help with treatment and hospitalization!

Vaginal atrophy: etiological aspects and modern approaches to therapy

Postmenopause is characterized by an estrogen deficiency state in women, caused by age-related decline and then cessation of ovarian function [1]. As is known, any epithelial tissue reacts to changes in the hormonal environment surrounding them in a similar way, but none of them can compare with the epithelium of the vaginal vault and cervix in the speed and clarity of the reaction to hormones, primarily to sex steroids [2]. Thus, the urogenital tract is particularly sensitive to decreased estrogen levels and approximately half of all postmenopausal women experience symptoms associated with urogenital atrophy (UGA), affecting sexual function and quality of life [3]. The clinical picture of urogenital disorders in the menopause includes symptoms associated with vaginal atrophy (vaginal atrophy (VA)) and urination disorders (cystourethral atrophy). Unlike vasomotor symptoms, which usually resolve over time, symptoms of vaginal atrophy typically begin in premenopause and progress postmenopause, leading to functional and anatomical changes [4]. 15% of premenopausal women and 40–57% of postmenopausal women experience symptoms of VA [5], such as vaginal dryness 27–55%, burning and itching 18%, dyspareunia 33–41%, as well as increased susceptibility to infectious diseases of the organs pelvis 6–8% [4], which significantly worsens health and negatively affects the general and sexual quality of life [6]. 41% of women aged 50–79 years have at least one of the symptoms of VA [10].

The walls of the vagina consist of three layers: the inner layer, which is lined with stratified squamous epithelium; middle muscular and outer connective tissue layers (or fibrous layer). Atrophic processes involving the connective tissue and muscle structures of the vagina, as well as the muscles of the pelvic floor, urethra, and bladder, are especially pronounced in the vaginal mucosa. It is known that in women, the vaginal mucosa consists of four main layers of epithelial cells: the basal layer; parabasal layer (or mitotically active); intermediate glycogen-containing layer; superficial (flaking) [11]. Estrogen receptors are located mainly in the basal and parabasal layers of the vagina and are practically absent in the intermediate and superficial layers [10]. Estrogen deficiency blocks the mitotic activity of the basal and parabasal layers of the epithelium of the vaginal wall, and, consequently, the proliferation of the vaginal epithelium [12]. The consequence of the cessation of proliferative processes in the vaginal epithelium is the disappearance of glycogen, a nutrient medium for lactobacilli, thus its main component, lactobacilli, is completely eliminated from the vaginal biotope [3, 12].

It is known that peroxide-producing lactobacilli, which predominate in vaginal microbiocinosis in women of reproductive age, play a key role in preventing the occurrence of diseases of the urogenital tract [10, 11]. Due to the breakdown of glycogen, which is formed in the vaginal epithelium, provided there is a sufficient amount of estrogens, lactic acid is formed, providing an acidic vaginal environment (within pH fluctuations from 3.8 to 4.4). Such a protective mechanism leads to suppression of the growth of pathogenic and opportunistic bacteria. During the postmenopausal period, the vaginal mucosa loses these protective properties, becomes thinner, and is easily injured, followed by infection not only by pathogenic, but also by opportunistic microorganisms.

Estrogens are the main regulators of physiological processes in the vagina. Estrogen receptors α are present in the vagina in premenopausal and postmenopausal women, while estrogen receptors β are completely absent or have low expression in the vaginal wall of postmenopausal women. The highest density of estrogen receptors is observed in the vagina and decreases in the direction from the internal genital organs to the skin. The density of androgen receptors, on the contrary, is low in the vagina and higher in the area of the external genitalia. Progesterone receptors are found only in the vagina and the epithelium of the vulvovaginal junction [10]. Since the cells of the vaginal stroma contain estrogen receptors, collagen, which is part of the connective tissue of the vaginal wall, is an estrogen-sensitive structure, the content of which decreases as estrogen deficiency progresses. Since estrogen receptors are located not only in the epithelium and stroma of the vaginal wall, but also in the vascular endothelium, in postmenopause there is a decrease in blood circulation in the vagina to the level of varying degrees of ischemia. In addition, estrogens are vasoactive hormones that increase blood flow by stimulating the release of endothelial mediators such as nitric oxide, prostaglandins, and endothelial hyperpolarizing factor. Such a progressive decrease in blood flow in the vaginal mucosa leads to hyalinization of collagen and fragmentation of elastic fibers, increasing the amount of connective tissue [12].

Estrogen receptors have also been found on autonomic and sensory neurons in the vagina and vulva. A study by TL Griebling, Z. Liao, PG Smith revealed a decrease in the density of sensory nociceptive neurons in the vagina during estrogen treatment. This feature may be useful in addressing the discomfort associated with VA, namely in relieving symptoms such as burning, itching and dyspareunia that many postmenopausal women experience [5, 10].

Atrophy of the vulvar and vaginal mucosa is characterized by thinning of the epithelium, decreased vaginal folding, pallor, the presence of petechial hemorrhages, and signs of inflammation. Also, due to involutive changes, there is a loss of tissue elasticity, subcutaneous fat, loss of pubic hair, and a decrease in the secretory activity of the Bartholin glands [3, 13, 14]. Typically, doctors diagnose vulvar and vaginal atrophy based on a combination of clinical symptoms and visual examination. Researchers are increasingly insisting on more objective and reproducible diagnostic methods, without excluding subjective patient complaints [13]. Historically, to diagnose VA, two main objective methods of diagnosing and assessing the effectiveness of treatment are required: vaginal pH, as well as calculation of the vaginal maturation index (VII, the predominance of cells of the basal and parabasal layers) [12, 13]. Interestingly, the degree of atrophic changes, as measured by the maturation index, does not always correlate with symptoms [15]. In a study of 135 menopausal female volunteers who completed a symptom assessment followed by a rating of “vaginal health” (assessing vaginal color, discharge, epithelial integrity and thickness, pH) and a maturation index measurement, researchers found a weak correlation between physical symptoms and maturation index.

Hormonal changes that occur throughout the life cycle affect the vaginal flora from birth to postmenopause. A decrease in estrogen during perimenopause and postmenopause leads to a decrease in the number of lactobacilli and a change in flora in general. According to SL Hillier, RJ Lau, a detailed analysis of the vaginal microflora of 73 postmenopausal women who did not take hormonal therapy did not reveal lactobacilli in 49% of cases. And among those in whom they were detected, the concentration of the latter was 10–100 times less than in premenopausal women [15]. In postmenopause, the most common microorganisms were anaerobic gram-negative rods and gram-positive cocci.

Despite the above, some women experience wasting symptoms soon after menopause, while others do not experience them until later in life. Among the factors that may increase the risk of developing urogenital atrophy, smoking is one of the most studied. Smoking has a direct effect on the squamous epithelium of the vagina, reducing the bioavailability of estrogen and reducing blood perfusion. Other hormonal factors that tend to be important are the levels of various androgens such as testosterone and androstenedione. It has been suggested that after menopause, women with higher levels of androgens, which support sexual activity, have fewer changes associated with atrophy [12]. In addition, VA is observed more often in women who have never given birth vaginally [16].

Considering the pathogenesis of the disease, estrogen therapy is the gold standard of treatment. All clinical guidelines for the treatment of UGA agree that the most common and effective treatment method is systemic or local hormonal therapy with estrogen in various forms, as it quickly improves the maturation index and thickness of the vaginal mucosa, reduces vaginal pH and eliminates the symptoms of VA [ 3, 11–13]. To treat UGA combined with symptoms of menopause, systemic hormonal therapy is used. In other cases, local treatment is preferred, which avoids most systemic side effects [12, 13]. Studies have shown that systemic hormone replacement therapy eliminates symptoms of VA in 75% of cases, while local therapy eliminates symptoms in 80–90%.

Estrogen-containing preparations for local use, presented in the form of cream, tablets, pessaries/suppositories, vaginal ring, may contain estriol, conjugated equiestrogens, estradiol or estrone. Of the three natural estrogens in the human body, estriol has the shortest half-life and the least biological activity. In Russia, there is many years of experience in the local use of estriol-containing drugs that have a pronounced colpotropic effect. Given the weak proliferative effect on the endometrium when using estriol, additional administration of progestogen is not required. Numerous studies have shown that daily use of estriol at a dose of 0.5 mg has a noticeable proliferative effect on the vaginal epithelium. Local use of estriol-containing drugs is a safe and effective approach to the prevention and treatment of VA, which has no restrictions on age and duration of treatment. Currently, in European countries there is a trend towards local use of low doses of estrogens estriol and estradiol.

In 2006, a Cochrane systematic review analyzed 19 clinical trials involving 4,162 postmenopausal women, randomized to vaginal estrogen products, and evaluating the efficacy, safety, and acceptability of therapy as an endpoint. Fourteen studies compared the safety of different drugs, seven focused on side effects and four on treatment safety and effects on the endometrium. Seven studies included placebo groups, and all showed improvement in patients taking hormonal therapy (Table).

The results of the analysis show that vaginal estradiol tablets are more effective than the vaginal ring and that both treatments are superior to placebo in relieving dyspareunia, vaginal dryness and itching. Conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) vaginal cream is superior to moisturizing creams in relieving dryness and increasing elasticity and blood flow to the vagina. However, no differences were found between the three therapies analyzed (CLE cream, estradiol tablets, and estradiol-releasing ring) with respect to parabasal cell count, karyopyknotic index, maturation index, and vaginal health index. In addition, there are also reports of no significant differences in endometrial thickness, hyperplasia, and side effects between the vaginal ring, cream, or tablet. However, a slight risk of vaginal bleeding was described in all studies that used different methods of topical estrogen therapy, as well as a possible increased risk of candidiasis [16].

A meta-analysis by Cardozo et al showed that vaginal estrogen administration is an effective treatment for VA. The combination of local and systemic therapy allows you to achieve results in a shorter time. In addition, low doses of topical estrogens: estradiol or estriol are as effective as systemically administered ones. A transdermal patch with a daily dose of 14 μg of estradiol has been shown to have similar effects on vaginal pH and maturation index as a vaginal ring with 7.5 μg of estradiol [17].

The beneficial therapeutic effect of topical hormonal therapy has also been noted in situations beyond the treatment of VA, such as reducing the risk of recurrent urinary tract infections and the development of overactive bladder. Based on the above, the estradiol-releasing ring has been approved as a treatment for dysuria and urge urinary incontinence. While systemic hormonal therapy, on the contrary, increases the incidence of stress urinary incontinence and kidney stones [10].

Thus, local therapy has a number of advantages compared to systemic administration of drugs. It avoids primary metabolism in the liver, has minimal effects on the endometrium, has a low hormonal load, minimal side effects, does not require the addition of progestogens, and has a mainly local effect.

From a practical point of view, and due to the similar effectiveness and safety of all topical estrogen preparations, the patient should be able to choose the drug that she considers most suitable for her. She should be informed that the effect is achieved after one to three months of treatment. Additional administration of progestogens is not necessary when using local forms of estrogens [18]. A 2009 review of topical hormone therapy stated that no studies observed endometrial proliferation after 6 to 24 months of estrogen use, so the literature thus provides reassurance regarding the safety of low-dose vaginal preparations with estrogen and non-estrogens. supports the concomitant use of systemic progestogens to protect the endometrium [13].

In addition to the above treatment methods for VA, today there are such as therapy using dehydroepiandrosterone, selective tissue estrogen complexes, selective estrogen receptor modulators and non-hormonal treatment methods, as well as combination drugs containing ultra-low-dose estriol and lactobacilli.

In the work of U. Jaisamrarn et al. evaluated for the first time the efficacy and tolerability of ultra-low dose estriol (0.03 mg) in combination with viable Lactobacillus acidophilus in the short and long term for the treatment of symptoms of VA. It was found that the combination of estriol and lactobacilli for 12 weeks was sufficient to achieve statistically and clinically significant results, including improvement in objective parameters (VIS, pH, proportion of lactobacilli in the vaginal microflora), as well as the quality of life of women [19].

A large number of publications are devoted to the use of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) gel for the treatment of VA [8]. DHEA is a sex hormone precursor that is produced by the adrenal glands and ovaries in addition to testosterone and estrogens. Subsequently, it undergoes biotransformation in peripheral tissues: in the brain, bones, mammary glands and ovaries. To date, specific receptors for DHEA have not been found, and therefore it is assumed that its action occurs through conversion to androgens and/or estrogens and interaction with their receptors, respectively. To date, most of the evidence for the beneficial effects of vaginally administered DHEA reported in five publications comes from a single randomized trial conducted by Labrie and colleagues. DHEA was used vaginally by 218 postmenopausal women for 12 weeks. Women were assigned to a placebo group taking 0.25% (3.25 mg), 0.5% (6.5 mg) or 1.0% (13 mg) vaginal cream daily. In patients receiving DHEA therapy, vaginal atrophy disappeared, while minimal changes in serum steroid hormone levels were observed, which remained within the normal range characteristic of postmenopause. Also in this study, there were positive effects on four aspects of sexual function: desire/interest, arousal, orgasm, and dyspareunia. DHEA 0.5% (6.5 mg) cream was found to be optimal for the treatment of vaginal atrophy and did not significantly affect serum estrogen levels [20].

Among the selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), ospemifene is the most advanced drug available. A 12-week, three-phase randomized trial involving 826 postmenopausal women examined the effectiveness of this drug at a dose of 30 mg, 60 mg compared with placebo. At weeks 4 and 12, ospemifene at the previously reported doses showed statistically significant increases in superficial cell counts, decreases in parabasal cells, and decreases in vaginal pH compared with placebo. Vaginal dryness was significantly reduced in both the 30 mg and 60 mg groups compared to placebo at week 12, while dyspareunia was reduced only in the 60 mg group. The study found that the side effect of hot flashes occurred in 9.6%, 8.3% and 3.4% of participants in the ospemifene 30 mg, 60 mg and placebo groups, respectively. Endometrial thickness from baseline to week 12 changed on average by 0.42 mm, 0.72 mm and 0.02 mm in participants in the above groups, respectively [21].

The combination of conjugated estrogens and the selective estrogen receptor modulator bazedoxifene, known as tissue selective estrogen complex (TSEC), was studied in a phase 3 study where 601 women were randomized to receive daily therapy: 20 mg bazedoxifene plus conjugated estrogens. .45 mg (BZA/CE), or bazedoxifene 20 mg plus 0.625 mg conjugated estrogens, or bazedoxifene 20 mg and placebo. The study found an increase in the proportion of superficial cells and a decrease in the proportion of parabasal cells from baseline to week 12, to a greater extent in the BZA/CE group compared with placebo and BZA alone. Vaginal pH did not change significantly from baseline to the end of the study in the BZA or placebo group, but decreased significantly in both BZA/CE groups. However, the decrease in vaginal pH was significantly lower in the BZA/CE 20 mg/0.625 mg group than in the placebo group. Most bothersome symptoms were significantly reduced by week 12 compared with placebo in the BZA/CE 20 mg/0.625 mg group, but not in the BZA/CE 20 mg/0.45 mg group. There were no significant differences in side effects or study discontinuations between groups. However, a higher incidence of vaginitis was noted in the treatment groups (BZA/CE) compared with placebo [22]. Thus, TSEC, namely bazedoxifene in combination with conjugated estrogens, represents an alternative to progestin therapy to protect the endometrium from estrogen stimulation while maintaining the beneficial effects of estrogen on menopause-related symptoms.

Despite the listed methods of treating VA, one should not forget about preventing the disease. Maintaining regular sexual activity is recommended in general for all women and in particular for menopausal women. This is because sexual intercourse improves blood circulation in the vagina, and seminal fluid also contains sex steroids, prostaglandins and essential fatty acids, which help maintain vaginal tissue [12].

Although the official prevalence of vaginal atrophy varies depending on the size and individual characteristics of the population studied, an increasing number of women are affected by this condition as the population ages. One study conducted by foreign colleagues showed that more than 60% of women experience symptoms of VA 4 years after postmenopause. However, only 4% of women aged 55–65 years associate the above complaints with vaginal atrophy, 37% know that these symptoms are reversible, and 75% of women believe that symptoms of VA negatively affect their lives. Given the sensitive nature of these symptoms, patients are hesitant to seek medical help and consequently suffer from progressive symptoms [10, 23]. Only 25% of women with symptoms of vaginal atrophy seek medical help. VA is a chronic and progressive condition [10]. A significant number of women with symptoms of VA do not even realize that effective treatment is possible. Timely informing patients about the causes of the above symptoms and the possibilities for eliminating them can quickly improve the condition of women and restore their interest in life and its quality. Thus, the problem of maintaining health and preventing diseases caused by aging has acquired particular importance in recent years. Due to its relevance, new drugs for the treatment of VA are currently being developed and introduced, which will allow an individualized approach to patient treatment.

Literature

- Vikhlyaeva E. M. Guide to gynecological endocrinology. M.: Medical Information Agency, 1997. pp. 227–360.

- Urogenital disorders in menopause (clinical presentation, diagnosis, hormone replacement therapy). dis. Dr. med. Sci. M., 1998.

- Santiago Palacios. Managing urogenital atrophy // Maturitas. 2009; 63:315–318.

- Sinha A., Ewies AAA Non-hormonal topical treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy: an up-to-date overview // Climacteric. 2013; 16: 305–312.

- Griebling TL, Liao Z., Smith PG Systemic and topical hormone therapies reduce vaginal innervation density in postmenopausal women // Menopause. 2012; 19: 630–635.

- Frank SM, Ziegler C., Kokot-Kierepa M., Maamari R., Nappi RE Vaginal Health: Insights, Views & Attitudes (VIVA) survey - Canadian cohort // Menopause Int. 2012.

- Rosano GMC, Vitale C., Silvestri A., Fini M. Metabolic and vascular effect of progestins in postmenopause // Maturitas. 2003; 46: 17–29.

- Hextall E. Esrogens in the funtion urethral tract // Maturitas. 2000; 36:83–92.

- Manukhin I. B., Tumilovich L. G., Gevorkyan M. A. Clinical lectures on gynecological endocrinology. M., 2003.

- Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society // The North American Menopause Society. 2013; 20(9):888–902.

- James H. Pickar. Emerging therapies for postmenopausal vaginal atrophy // Maturitas. 2013; 75:3–6.

- Camil Castelo-Branco, Maria Jes´us Cancelo, Jose Villero, Francisco Nohales, Maria Dolores Juli´a. Management of post-menopausal vaginal atrophy and atrophic vaginitis // Maturitas. 2005; 52:46–52.

- Sturdee DW, Panay N. Recommendations for the management of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy // Climacteric. 2010; 13:509–522.

- Basaran M., Kosif R., Bayar U., Civelek B. Characteristics of external genitalia in pre-and postmenopausal women // Climacteric. 2008; 11: 416–421.

- Paul Nyirjesy. Postmenopausal Vaginitis. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2007; 9:480–484.

- Suckling J., Lethaby A., Kennedy R. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women // Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006.

- Gupta P., Ozel B., Stanczyk FZ, Felix JC, Mishell Jr. DR The effect of transdermal and vaginal estrogen therapy on markers of postmenopausal estrogen status // Menopause. 2008; 15(1)): 94–97.

- Pitkin J., Rees M. British Menopause Society Council. Urogenital atrophy // Menopause Int. 2008; 136–137.

- Jaisamrarn U., Triratanachat S., Chaikittisilpa S., Grob P., Prasauskas V., Taechakraichana N.. Ultra-low-dose estriol and lactobacilli in the local treatment of postmenopausal vaginal atrophy // Climacteric. 2013; 16: 347–355.

- Labrie F., Archer D.F., Bouchard C. et al. Intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (prasterone), a highly efficient treatment of dyspareunia // Climacteric. 2011; 14: 282–288.

- Bachmann GA, Komi JO The Ospemifene Study Group. Ospemifene effectively treats vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: results from a pivotal phase 3 study // Menopause. 2010; 17(3):480–486.

- Kagan R., Williams RS, Pan K., Mirkin S., Pickar JH A randomized, placebo-and active-controlled trial of bazedoxifene/conjugated estrogens for treatment of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women // Menopause . 2010; 17(2):281–289.

- Kingsberg SA, Krychman ML Resistance and barriers to local estrogen therapy in women with atrophic vaginitis // J Sex Med. 2013; 1567–1574.

A. V. Glazunova S. V. Yureneva1, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor

FSBI NTs AGiP im. V. I. Kulakova Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow

1 Contact information

Abstract. According to forecasts to 2030 there will be 1.2 bln women in postmenopause. The state of estrogen deficiency in climacterical period cause vaginal atrophy with 15–57% of women. The latest data on the problem of pathogenesis, clinical manifestations and therapy of this state are provided in review.

2. Reasons

The main reason for the initiation and progression of VVA is considered to be a deficiency of estrogen hormones that activate and regulate the activity of the organs of the female reproductive system. The lack of estrogen results in disturbances in cellular nutrition and the composition of the vaginal microbiome, an imbalance between the components of connective tissue (collagen and elastin), a gradual decrease in microcirculation and blood supply to the mucous membranes and submucosal layer (which, in turn, leads to a reduction in the secretory activity of the vaginal exocrine glands).

Visit our Gynecology page

Diagnosis of atrophic (senile) colpitis

- Gynecological examination on a chair.

- Vaginal smears (cytology), including for hidden infections.

- Colposcopy.

- Determination of vaginal pH.

In gynecology, during examination with the help of mirrors, atrophy of the mucous membrane is noticeable, which is pale in color, dotted with microcracks and areas devoid of epithelium, they begin to bleed after touching. With secondary infection, focal or diffuse vaginal hyperemia with a grayish coating and purulent discharge is detected.

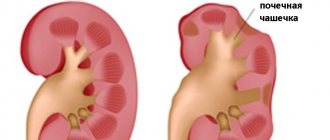

On examination, women of the menopausal period may reveal atrophy of the cervix and body of the uterus with a size ratio of 2:1, which are characteristic of childhood. Severe degenerative processes may be accompanied by complete or partial fusion of the vaginal vaults.

During colposcopy, attention is paid to the presence of petechiae and dilated capillaries on the pale, thin mucosa. When performing the Schiller test, uneven weak coloring is obtained.

A study on vaginal pH in menopause shows an index in the range of 5.5–7 (for childbearing age - 3.5–5.5).

Smear cytology in elderly women helps to detect the predominance of cells of the basal and parabasal layers. When performing microscopy of a vaginal smear, a sharp decrease in the titer of vaginal bacilli, an increase in the number of leukocytes, and the presence of various opportunistic microflora are detected.

To exclude specific vaginitis in older patients, PCR diagnostics of vaginal scrapings is performed. If an STI is detected, a referral to a venereologist is given.

3. Symptoms and diagnosis

The thinning and ischemia of the mucous membranes caused by the atrophic process entails a progressive deficiency of vaginal hydration. Dryness is the most common complaint - it is presented by almost all patients who apply for vulvovaginal degenerative-dystrophic phenomena. Other typical complaints include itching, burning, irritation, general dyspareunia (lack of satisfaction with sexual life, often painful intercourse, weakening of the intensity of coital sensations, etc.), a persistent decrease in the emotional background of the depressive type, sharply low ideas about one’s own attractiveness, hypolibidemia and avoidance of sexual intercourse (which in some cases becomes the cause of serious family and sexual disharmony). A separate problem is atrophic vulvovaginitis - inflammation caused by traumatization of the mucous membranes with insufficient elasticity, volume, turgor and hydration. Many patients note the appearance of abnormal discharge, often with heavy bloody impurities.

Taken together, such manifestations inevitably affect the quality of everyday life, social and sexual activity, and the general psychological state of a woman. Contrary to the misconception of many (if not most) women suffering from VVA, this condition is by no means considered by modern gynecology as a normal consequence of involutional (age-related) processes that does not require treatment.

Diagnosis of vulvovaginal atrophy begins with the collection of a detailed medical history (age, number of full-term and terminated pregnancies, presence/absence of sexual activity, its nature and frequency, menstrual status, etc.). A standard gynecological examination is performed, the condition of the mucous membranes and skin of the genitals is assessed (thinning, pallor, the presence of petechiae, bloody effusion, etc.). Laboratory tests are prescribed - pH-metry, bacterial culture or serological analysis, histological analysis of a tissue sample, blood tests (general clinical, hormonal and others as indicated), as well as instrumental studies of the pelvic organs as necessary (transvaginal ultrasound, X-ray contrast urography, etc.) . An important task is differential diagnosis with symptomatically similar conditions.

About our clinic Chistye Prudy metro station Medintercom page!

Causes of postmenopausal atrophic colpitis (vaginitis)

The disease develops due to the fact that, against the background of estrogen deficiency, the proliferation of the vaginal mucosa also stops. The secretion of the glands that produce lubrication also decreases. Against this background, mucosal atrophy and increased sensitivity develop. Also, due to drying out, the tissues become more vulnerable, which causes periodic spotting bleeding.

At the same time, a change in the vaginal microflora occurs, during which opportunistic microorganisms begin to become activated. They cannot fully protect tissues from the penetration of infections introduced during gynecological manipulations and sexual intercourse, which is why inflammatory agents penetrate through microtraumas.

A particular risk of atrophic (age-related) colpitis is observed in women who have experienced the following phenomena:

- early menopause;

- diabetes;

- hypothyroidism;

- complete loss of function of both ovaries;

- insufficient hygiene in the intimate area;

- wearing low-quality underwear;

- use of scented detergents for washing.

If manifestations of the disease are detected, a woman must visit a gynecologist to undergo full therapy.

4.Treatment

Currently existing approaches to the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy are mainly palliative and symptomatic. In many cases, to effectively relieve discomfort, local use of vaginal moisturizers (lubricants), preferably non-hormonal, is sufficient.

Estrogen-containing ointments, gels, suppositories, etc. used with caution and should be discontinued as soon as a satisfactory and reliable effect is achieved.

In more serious cases, systemic oral hormone replacement agents may be prescribed.

Gymnastics of the pelvic muscles, normalization of diet and lifestyle are of great importance. In some cases, an effective remedy is a set of measures to carefully and gradually stretch the vagina; in others, rational vitamin therapy, eradication of associated urogenital infections, restoration of the natural microbiome, etc. are mandatory. In general, the treatment regimen in all cases is strictly individual, and one of the main factors of therapeutic success is timely seeking help.

Symptoms of atrophic colpitis

In many women, the pathology has a sluggish course and does not cause severe discomfort, which is why it is ignored until it worsens. In a number of patients, the symptoms of the disease manifest themselves acutely from the very beginning and cannot be ignored. Most patients with pathology have the following complaints:

- burning pain in the vagina;

- intense itching;

- pain during sex;

- discharge of ichor after sex, as well as defecation or taking a smear from the vagina.

If, after the vaginal wounds become infected, full treatment is not carried out, a secondary infection is added to the atrophy of the mucous membrane, which affects the bladder, causing the woman to develop the following symptoms:

- urinary incontinence during physical activity or laughter;

- inability to hold back the urge to urinate for a long time.

In such a situation, therapy will be somewhat more complicated, since treatment of the bladder will also be required.

Treatment of atrophic (age-related) colpitis

Treatment for senile (senile) colpitis in postmenopause is aimed at restoring full trophism of vaginal tissue. For this purpose, hormone replacement therapy is carried out. It prescribes medications for oral use or in the form of patches, as well as ointments and suppositories for topical use.

When atrophic vaginitis is mild, phytoestrogens are used, which, due to their plant origin, have a milder effect on the body. Hormone replacement therapy is designed for continuous use for up to 5 years.

Non-hormonal treatment of senile colpitis if it is impossible to use estrogens includes douching or baths with solutions of medicinal herbs that have local antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, and reparative properties. If inflammation with a specific pathogen is detected, etiotropic local therapy is carried out.

To monitor the effectiveness of therapy, dynamic colposcopy, cytology, and vaginal pH-metry are performed.

With proper treatment of senile colpitis, all unpleasant manifestations are completely eliminated, and the woman does not experience discomfort. Delay in treatment becomes the reason for its greater complexity and not always complete elimination of the symptoms of the pathology.

Prevention and prognosis for senile colpitis

The condition for preventing the development of the disease is constant observation by a gynecologist with regular examinations and the prescription of hormone replacement therapy during menopause. In addition to improving the condition of the vaginal mucosa, hormonal drugs reduce the symptoms of menopause and reduce the risk of developing osteoporosis and heart disease.

Nonspecific prevention of postmenopausal atrophic vaginitis comes down to preventing the onset of early menopause. To do this, it is advised to quit smoking, eat rationally, perform dosed physical activity, and avoid stress. For patients prone to developing this disease, it is important to strengthen their immune system, take good care of personal hygiene, and wear cotton underwear.

The prognosis for colpitis is favorable in terms of life expectancy, however, due to the tendency of the disease to relapse, its quality may decrease.

The Consultative and Diagnostic Center (formerly the NDC) in St. Petersburg provides diagnostic and therapeutic assistance to patients with gynecological diseases of various etiologies. Make an appointment with a gynecologist from our call center operators and come for treatment and diagnosis of diseases of the female genital area.

How is laser treatment for vaginal atrophy performed?

The laser treatment procedure for vaginal atrophy involves a course of 3 procedures with an interval of 4 weeks. The duration of one procedure does not exceed 15-20 minutes.

Preparation for laser treatment should be the same as for a regular visit to the gynecologist.

No anesthesia is required. The intervention is performed under local anesthesia with lidocaine cream or spray.

After examination and antiseptic treatment of the vagina and external genitalia, a special attachment is inserted into the vagina and laser treatment of its walls is carried out. Scanning is carried out circularly and sequentially, capturing all walls.

The second stage involves treating the posterior wall of the vulva and labia. If necessary, simultaneous treatment of the inner thighs is possible to remove pigmentation.

Recovery from laser treatment is easy and takes less than a week. No special treatment is required.