Metformin

Lactic acidosis

Lactic acidosis is a very rare but serious (high mortality rate if not treated promptly) complication that can occur due to accumulation of metformin. Cases of lactic acidosis when taking metformin occurred mainly in patients with diabetes mellitus with severe renal failure.

Other associated risk factors should be taken into account, such as decompensated diabetes mellitus, ketosis, prolonged fasting, alcoholism, severe infectious disease, liver failure, any condition associated with severe hypoxia and concomitant use of drugs that can cause the development of lactic acidosis (see section " Interaction with other drugs"). This may help reduce the incidence of lactic acidosis.

The risk of developing lactic acidosis should be taken into account when nonspecific signs appear, such as muscle cramps accompanied by dyspeptic disorders, abdominal pain and severe asthenia. Lactic acidosis is characterized by acidotic shortness of breath, abdominal pain and hypothermia followed by coma. Diagnostic laboratory parameters are a decrease in blood pH (less than 7.35), lactate content in the blood plasma over 5 mmol/l, increased anion gap and lactate/pyruvate ratio. If metabolic acidosis is suspected, stop taking the drug and consult a doctor immediately.

Surgical operations

Metformin should be discontinued during surgery under general, spinal or epidural anesthesia. Metformin therapy can be continued no earlier than 48 hours after surgery or resumption of food intake, provided that renal function has been examined and found to be normal.

Kidney function

Since metformin is excreted by the kidneys, before starting treatment and regularly thereafter, it is necessary to determine QC:

- at least once a year in patients with normal renal function;

- every 3-6 months in patients with CC 45-59 ml/min;

- every 3 months in patients with CC 30-44 ml/min.

In the case of CC less than 30 ml/min, the use of the drug is contraindicated.

Particular caution should be exercised in case of possible impairment of renal function in elderly patients, with dehydration (chronic or severe diarrhea, repeated bouts of vomiting), and with the simultaneous use of antihypertensive drugs, diuretics or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Heart failure

Patients with heart failure have a higher risk of developing hypoxia and renal failure. Patients with chronic heart failure should have cardiac and renal function monitored regularly while taking metformin.

Taking metformin in acute heart failure with unstable hemodynamic parameters is contraindicated.

Children and teenagers

The diagnosis of type 2 diabetes mellitus must be confirmed before starting treatment with metformin.

In clinical studies lasting 1 year, metformin was shown to have no effect on growth and puberty. However, due to the lack of long-term data, careful monitoring of the subsequent effects of metformin on these parameters in children, especially during puberty, is recommended. The most careful monitoring is necessary for children aged 10-12 years.

The use of iodine-containing radiocontrast agents

Intravascular administration of iodinated radiocontrast agents can lead to the development of renal failure and accumulation of metformin, which increases the risk of developing lactic acidosis. Metformin should be discontinued, depending on renal function, 48 hours before or during an X-ray examination using iodinated contrast agents, and not resumed until 48 hours after it, provided that during the examination, renal function was found to be normal.

Other precautions:

Patients are advised to continue to follow a diet with even carbohydrate intake throughout the day. Overweight patients are recommended to continue to follow a hypocaloric diet (but not less than 1000 kcal/day).

It is recommended that routine laboratory tests be performed regularly to monitor diabetes mellitus.

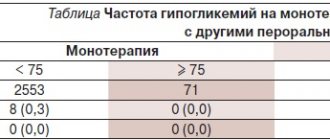

Metformin does not cause hypoglycemia when used alone, but caution is recommended when used in combination with insulin or other hypoglycemic agents (for example, sulfonylureas, repaglinide, etc.).

The use of metformin is recommended for the prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus in persons with prediabetes and additional risk factors for the development of overt type 2 diabetes mellitus, which include:

- age less than 60 years;

- body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2;

- history of gestational diabetes mellitus;

- family history of diabetes mellitus in first-degree relatives;

- increased concentration of triglycerides;

- reduced concentration of HDL cholesterol;

- arterial hypertension.

Metformin did not affect fertility in male or female rats when administered at doses three times the maximum recommended daily dose for humans.

Is Metformin a cure for everything? Yes, but no

We are here, in the editorial office of “XX2 Century”

, we love metformin very much and talk about it at every opportunity. Today it suppresses the growth of cancer cells, tomorrow it fights inflammation, the day after tomorrow it helps you lose weight, and next week it completely prolongs life. Readers might have the impression that this medicine overcomes any disease. Unfortunately, this is not entirely true and almost every piece of good news comes with a “yes, but.” So we decided to write about metformin again - this time a long text that will explain to those who missed everything where this drug came from, what it treats and how successful it is.

Story

It all started with grass. Goat's rue, aka goat's rue, aka Italian ferret, aka, scientifically, Galega officinalis

- a perennial herbaceous plant. In medieval Europe, it was used to treat frequent urination - one of the symptoms of diabetes - and some other diseases. It is difficult to say how long goat's rue has been used in folk medicine, but it is known that the famous English aesculapian Nicholas Culpeper mentioned it back in 1652 in the book “The English Physician”.

At the end of the 19th century, scientists took a closer look at goat's rue and found that it contains large amounts of guanidine (this colorless crystalline substance was first synthesized in 1861). In 1918, during experiments on rabbits, scientists showed that guanidine lowers blood glucose levels. But the compound turned out to be too toxic to treat people, so scientists began experimenting with guanidine derivatives. In 1922, Emil Alphonse Werner and James Bell synthesized N, N-dimethylguanidine to obtain dimethylbiguanidine, known to us as metformin, and seven years later the German scientist Karl Slotta tested it on animals . There were other drugs based on guanidine - galegin (isoamylene-diguanidine), biguanides Syntalin A and B. Synthalins were even used in clinical practice for some time, but after the industrial production of insulin began (in 1923 by Eli Lilly and Company

started selling it under the name “Iletin”), they forgot about guanidine derivatives.

Galega officinalis

or goat's rue is the grandfather of the most popular antidiabetic drug.

In 1949, metformin came into the hands of Philippine infectious disease specialist Eusebio Garcia. He called the substance “flumamine” and used it to treat influenza and malaria. A year later, in the article Fluamine, a new synthetic analgesic and antiflu drug, Garcia said that a single injection of the drug relieved the headaches of thirty patients and completely cured them in 24 hours. The doctor did not know the exact mechanism of action, and suggested that flumamine lowers the concentration of sugar in the blood, but did not provide any evidence.

These speculations were enough to interest another physician, the Frenchman Jean Stern, a specialist in diabetology. He conducted experiments on dogs, rats and rabbits and found that six months of treatment had no effect on their development or liver function. Even during the autopsy, no anomalies were found. Stern conducted clinical trials on humans, called the drug a “glucophage” (“sugar eater,” similar to a bacteriophage) and began treating diabetics with it.

French doctor Jean Stern and the hospital where he studied the properties of metformin.

Metformin almost immediately had competitors - the more powerful phenoformin and buformin. But these drugs caused lactic acidosis - a dangerous condition that is accompanied by depression of the central nervous system, impaired breathing, cardiovascular function and urination. Therefore, by the end of the 70s they were no longer used in most countries. And that’s when metformin became the main alternative to insulin. It was sold in France and the UK in the late 50s, in Canada in the 70s, and only entered the American market after approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1994 year. There he quickly became a “bestseller”

What do we know about metformin

Metformin is now considered a “first-line drug” for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Its main advantage is that it practically does not cause hypoglycemia, which distinguishes it from insulin and another class of glucose-lowering drugs - sulfonylurea derivatives. Metformin reduces blood glucose concentrations by inhibiting its production in the liver, while sulfonylureas increase the release of insulin from beta cells in the pancreas. In addition, it does not promote weight gain. Of course, it also has side effects, unpleasant, but not fatal: the most common are gastrointestinal disorders, in particular nausea, vomiting, flatulence and diarrhea. And reducing appetite is even beneficial.

Much of what we know about the health effects of metformin comes from clinical studies. This drug was originally developed to lower blood sugar, and was studied, of course, primarily in the context of diabetes. In order to talk about the advantages and disadvantages of metformin, you need to talk at least a little about how doctors obtained this information - otherwise the story will turn into “scientists have proven it.” Here are some of the most significant clinical trials on type 2 diabetes:

- The University Group Diabetes Program, UGDP (University Group Diabetes Program)

- United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study, UKPDS (British Prospective Diabetes Study)

- Diabetes Prevention Program, DPP (Diabetes Prevention Program)

The UGDP was the first randomized clinical trial focused on diabetes. It involved 1,027 people, the study lasted 21 years, from 1960 to 1981, and the first results were published in 1970. Scientists wanted to find out which medicine is most effective in preventing the development of cardiovascular complications. The clinical trial was subject to fierce criticism, including due to errors in randomization. However, the FDA found no reason to disbelieve its findings. Participants were not taking metformin, but the UGDP declared another drug in the same class, phenformin, ineffective, and as a result, the “similar” drug was not approved for use in the United States. It was thanks to the UGDP that the drug's entry into the market in this country was delayed for many years. UKPDS was the largest clinical study at that time - it included 5102 patients with type 2 diabetes. The test lasted 20 years, from 1977 to 1997. UKPDS was meant to answer the question: can intensive blood glucose control prevent complications, and what is the best medicine to do this? Participants were taking first-generation sulfonylureas, insulin, or following a diet. After the publication of the results, doctors began to recommend metformin more often.

3,234 people participated in the DPP The goal of the study was to find the most effective way to prevent type 2 diabetes in people with prediabetes. To do this, one group was given diet, exercise and lifestyle changes, another was given metformin, and the third was given a placebo. After the clinical trial, they conducted another one - the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study, DPPOS, or, in Russian, “Diabetes Prevention Program: Study of the Outcomes.” Doctors studied the health status of DPP participants after 15 years.

During the UKPDS, only overweight patients received metformin. The results showed that the drug reduced the risk of death from diabetes complications by 42% and all-cause mortality by 36%. A good result, but not so impressive considering that the drug was compared to a regular diet. The risk of cardiovascular complications in patients on metformin, insulin and sulfonylureas was practically no different. When paired with urea derivatives, the drug even increased mortality. But, unlike other drugs, metformin did not promote weight gain and was less likely to cause hypoglycemia. Therefore, scientists have proposed no less than metformin as a first-line drug in the treatment of obese patients. This marked the beginning of his popularity.

DPP/DPPOS showed that taking metformin could reduce the risk of developing diabetes in people with prediabetes by 31%. But it’s better to change your lifestyle - in this case, the incidence is reduced by 58%. Good old exercise and diet turned out to be almost 2 times more effective. But the drug had another advantage - metformin helped to lose weight. People with prediabetes who took the drug lost an average of two kilograms. The effect lasted as long as the study participants took the pills, and the medicine was well tolerated.

Of course, there have been other studies of metformin and even meta-analyses of these studies. However, we still do not know everything about the advantages and disadvantages of this drug. For example, scientists are still trying to figure out how metformin affects the development of cardiovascular diseases and mortality - data on this matter is contradictory. A 2011 review of 30 papers found that a diabetes drug did neither significant harm nor significant benefit to the heart, and only performed well when compared to a placebo or no treatment at all. A 2021 paper that analyzed 300 studies found that there was no difference at all between nine classes of glucose-lowering drugs in terms of mortality and cardiovascular disease. However, the authors of the analysis acknowledge that the selected articles had a high risk of bias - more than half of the publications presented information selectively, and sponsors participated in the work on them. On the other hand, a recent study based on 17 publications shows that in patients with chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure and chronic liver failure, metformin does reduce mortality.

New application

In Russia and the USA, metformin is approved only for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, but they are also trying to treat other diseases. And the more that becomes known about the mechanisms of action and the effect of the drug on the body, the more actively they are looking for new uses for it.

It has long been known that taking metformin is accompanied by weight loss. DDP and DDPOS did not open doctors' eyes, but only confirmed previous observations. Therefore, doctors tried to treat healthy obese people with metformin. One of the first such studies was published in 1970 in the Lancet

. Scientists compared the effectiveness of metformin and fenfluramine on the example of 34 women aged 22-59 years. After 8 weeks of therapy, they concluded that fenfluramine worked better and had fewer side effects.

Work from 1998 and 2001 rehabilitated the glucose-lowering drug and showed that it reduced weight in non-diabetics, but a later meta-analysis came out that called these results into question. The scientists selected 57 studies and excluded 48 of them because they did not meet clinical trial standards. There were only 9 left - and after analysis it became clear that there was not enough data on the effectiveness of metformin. Three years later, another review came out and confirmed the results of the previous one. Metformin seemed to reduce weight by 3-9 kilograms, but the sample of such studies was small, the duration was short, and the design was “weak.” In addition, in addition to taking the medicine, the participants did physical exercise - try to figure out what exactly helped them lose weight. Several longer trials without these shortcomings showed only minor weight loss.

Four years ago, the results of perhaps the largest clinical study devoted to the treatment of obesity in non-diabetics were published. If in previous works we were talking about three to four dozen people, now there were 200 volunteers. 20% were unable to lose weight at all, and 9 people gained it. The remaining study participants lost an average of 5% of their body weight, and the drug helped people with impaired insulin sensitivity the most. But there was also a methodological pitfall in this study: there was no randomization of the control group.

Overweight children and adolescents are also treated with metformin, but not particularly successfully. In 2021, Cochrane, an international NGO that studies the effectiveness of health technologies, presented a systematic review and showed that not only metformin, but also other drugs are ineffective in this population. And the quality of the available data leaves much to be desired. In general, doctors admit that it is too early to recommend a diabetic drug for the treatment of obesity for both children and adults. The problem is still solved mainly by diet and exercise.

Another use of metformin is in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). PCOS is a condition in which women's levels of male hormones (androgens) increase, the functioning of the ovaries is disrupted and the menstrual cycle is disrupted. As a result, ovulation does not occur, and it becomes difficult (although not always impossible) to get pregnant. Many patients experience excess hair growth on the face and body, acne appears, and about half gain excess weight. It was not possible to fully understand the causes of PCOS, and it is not possible to cure it once and for all. But it is already known that the disease is associated with tissue insensitivity to insulin, and women with this syndrome have an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Metformin, which fights insulin resistance, comes in handy here.

But it's not that simple. In 1994, the drug worked well - then Venezuelan scientists conducted a study with the participation of 29 women, 7 of whom restored their menstrual cycle, and three spontaneously became pregnant. “Many, if not all, of the metabolic disorders of PCOS can be reversed with metformin,” the authors wrote. True, they immediately stipulated that they did not perform randomization and did not use a placebo for comparison. However, larger and more sophisticated clinical trials in 2006-2007 did not confirm the optimistic assumptions. Metformin did not stimulate ovulation particularly effectively and was inferior to clomiphene (trade name Clostilbegit).

According to the clinical guidelines of the International Endocrine Society, the diabetic drug helps with metabolic disorders and irregular periods, but has limited or no effectiveness in treating infertility, acne and excess hair growth. Participants in a seminar organized by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine came to a similar conclusion. They recommended metformin only for women with impaired glucose tolerance. But a 2014 Cochrane review says the drug is more effective than placebo and increases the chance of getting pregnant. True, the quality of the evidence base of the studies was considered low, and the likelihood of error was considered high.

And metformin, theoretically, can help fight cancer. But to what extent these hopes are justified is still unknown. They began to take a serious look at the medicine from this side only 12 years ago - an insignificant period if you remember how long it lasted, for example, UKPDS. In 2005, Josie Evans and her colleagues from the University of Dundee reported that taking metformin reduced the incidence of cancer among diabetics by 23%. They came to these conclusions after analyzing data from the DARTS electronic medical database.

The publication inspired other doctors, and they began to double-check their colleagues’ findings using other medical registries. Gradually, more and more studies confirmed the benefits of metformin. Reviews of scientific papers appeared that showed a decrease in incidence at the level of 31-34%. Then - experiments on cell cultures and mice. It turned out that in rodents, under the influence of a diabetic drug, the growth of tumors slows down by as much as 50% - however, the drug was fed to them in doses exceeding human doses.

Why can’t we please readers and say that we have finally found a new effective cure for cancer? For two reasons. Firstly, there is no abstract “cancer” - it is a collection of different oncological diseases. How effectively metformin combats each of these needs to be tested in clinical trials, a process that is far from complete. Second, the reliability of the data that generated early enthusiasm has been called into question. In two dozen papers, errors were found that could distort the results. And where they didn’t find it, they didn’t find a connection between metformin and cancer incidence. In general, more time is needed, more research is needed.

Metformin and aging

If metformin is mentioned in the media, the article is probably talking about life extension. Gerontologists look to the old drug with hope, and they have good reason for this. Firstly, in recent years, scientists have begun to actively study the molecular and genetic mechanisms of aging. Research shows that calorie restriction increases the lifespan of mice and rats by about 30 to 40%. According to an article published this year, such “therapeutic fasting” also prolongs the life of primates. “What does metformin have to do with it?” you ask. According to some scientists, metformin causes approximately the same changes in the body as calorie restriction: it increases sensitivity to insulin, lowers cholesterol, and improves physical condition. And gene expression in rodents fed metformin resembles that in animals on a low-calorie diet.

So scientists set out to test the drug’s effect on model organisms. Caenorhabditis elegans worms treated with metformin lived 18-36% (depending on the dose) longer than their relatives from the control group. Mice - by 5%. By the way, similar experiments were carried out here in Russia, at the Oncology Research Institute named after. N. N. Petrova. Scientists fed metformin not to ordinary rats, but to a breed created specifically for studying hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. In such animals, the average life expectancy increased by 37.8%. Gerontologists even got to crickets: in the species Acheta domesticus, after treatment with an antidiabetic drug, the maximum life expectancy was 138% compared to the control group.

The next logical step would be to conduct human trials. The results of one such study have already been published. Scientists analyzed data from 180,000 people: 78,000 had diabetes and took metformin, 12,000 took sulfonylureas, and 90,500 were healthy. This information was obtained not from a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, but from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. The results showed that diabetics on metformin live 15% longer than healthy people. The media wrote about a drug that can prolong life, but some scientists' work entitled “Can people with type 2 diabetes live longer than healthy people?” I wasn't impressed at all. Here's what Kevin McConway, a professor of applied statistics at the British Open University, said about it:

“The title of the article is misleading because someone who reads it may misunderstand it - in fact, this study cannot answer the question asked for reasons I will give below, and it seems as if doctors have reason to recommend metformin for healthy people. But this is not what the study is about.

In the press release, Craig Curry says, “Once a person develops diabetes, their life expectancy is shortened by an average of 8 years,” and goes on to explain why. If diabetics live so much shorter than healthy people, how can they “live longer than those who don't have diabetes,” as the article and press release headlines say?

That's because the study focused on a period of time when diabetic patients were receiving metformin as first-line therapy (this group was also compared with those who received sulfonylureas as first-line therapy). At some point, many patients will be transferred to second-line therapy because their diabetes or its symptoms have worsened. But at this point the research simply ends.

So the quote about reducing life expectancy in patients with type 2 diabetes by 8 years is talking about the patient's entire life after diagnosis, including the period when they are on more aggressive second-line therapy. But the study only takes into account the period of time before a change in treatment regimen. This won’t fit into a succinct headline, but it’s important to note that it’s not all that simple.

But if the survival rate of diabetics taking metformin is significantly higher than that of healthy people, albeit for a limited period of time, doesn't that mean that people who don't have diabetes should take metformin to live longer? No, it doesn't mean that. This apparent difference may be due to something other than metformin. […]

The difference in survival between diabetics on metformin and controls was statistically significant, but essentially quite small and likely within the range that can be explained by residual confounding (the influence of other variables not taken into account in the analysis).”

In addition, it would be remiss not to mention that the study was funded by pharmaceutical companies AstraZeneca

and

Bristol-Myers Squibb

.

Employees of these firms had access to the study data, although the article says they had no influence on the analysis, peer review or publication process. And the scientists themselves are quite familiar with the pharmaceutical industry. Five worked for Pharmatelligence

, a research consulting company that receives grants from drug manufacturers.

Another was an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb

. This in itself does not make the results unreliable, but, you see, it is somewhat alarming. Especially considering the fact that both sponsoring companies produce metformin.

So, without full-fledged clinical trials, this issue cannot be understood. One of the first studies on the connection between metformin and aging was to be the Metformin in Longevity Study. But since its launch in 2014, no information has appeared about it. Preliminary results were supposed to be obtained two years ago, but since then not a single publication has been published.

Another clinical trial is approaching - Targeting age with Metformin (TAME). This double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study is the gold standard, just the way we like it. It will be attended by 3,000 people aged 65 to 79 years. TAME is quite unusual for several reasons. Firstly, it is aimed at studying something that does not seem to exist. Aging, from a medical point of view, is not a disease. There is also no generally accepted biomarker by which one could understand whether this process is slowing down or not. Therefore, the goal of the study is to determine whether metformin can slow down the development of age-related diseases: cardiovascular, neurological, oncological, and so on.

Scientists hope they can set a precedent so that in the future the FDA will recognize aging as an “indication,” a condition that can be treated. "I think the FDA would be more likely to accept something called 'comorbidities' than something called 'aging,'" said Nir Barzilai, the team's chief scientific officer. - Even in our... in my opinion, old age is not a disease. It's human nature, you know! We are born, we die, and in between we grow old... I mean, “I don’t care what you call it, as long as I can delay it.”

Another unusual detail is that the study is not sponsored by pharmaceutical companies or the government. Funds are raised by the American Federation for Aging Research, and anyone can donate. According to Barzilai, conducting clinical trials will cost "$50 million, give or take 20 million." The results will not come soon: it will take some time to raise money, the research itself will last 3-4.5 years, plus time for processing and publishing the data. But when it comes to prolonging life, you can wait.

You might be interested in:

Metformin may be helpful for autism.

Metformin Pharmland 500 mg and 850 mg No. 30, tablets

The effect of metformin is enhanced by NSAIDs, MAO inhibitors, oxytetracycline, ACE inhibitors, clofibrate derivatives, cyclophosphamide, beta-blockers. When metformin is used together with sulfonylurea derivatives, insulin, acarbose and salicylates, the hypoglycemic effect may be potentiated. Compatible with sulfonylurea derivatives and insulin. Nifedipine increases absorption, Cmax, and prolongs the elimination of metformin.

The effect of metformin is weakened by phenothiazines, thyroid hormones, estrogens, oral contraceptives, phenytoin, nicotinic acid, calcium antagonists, isoniazid. Therefore, more frequent monitoring of blood glucose levels is necessary in patients receiving these drugs, especially at the beginning of treatment. If necessary, the dose of the drug is adjusted both during such treatment and after its cessation. The simultaneous use of guar gum or cholestyramine interferes with the absorption of the drug and reduces its effect.

With simultaneous use of the drug metformin with danazol, a hyperglycemic effect may develop (this combination is not recommended). When using the drug metformin and chlorpromazine together, it should be taken into account that the antipsychotic, when used in high doses, reduces the release of insulin and increases the level of glucose in the blood (this may require dose adjustment of metformin under the control of blood glucose levels).

With simultaneous injections of beta 2-sympathomimetics, the hypoglycemic effect of metformin may be weakened (it is necessary to monitor blood glucose levels and, if necessary, prescribe insulin). The effect of metformin is weakened by thiazide and other diuretics. Furosemide increases the Cmax of metformin by 22%. Metformin reduces Cmax and T1/2 of furosemide by 31% and 42.3%, respectively.

The simultaneous use of loop diuretics and metformin can lead to lactic acidosis due to the possible development of functional renal failure. When administered together, GCS (for systemic and local use) affect the effectiveness of metformin, reducing glucose tolerance and increasing plasma glucose levels, in some cases causing ketosis (if it is necessary to use such a combination, a dose adjustment of metformin is required to control blood glucose levels) . Drugs (amiloride, digoxin, morphine, procainamide, quinidine, quinine, ranitidine, triamterene and vancomycin) secreted in the tubules compete for tubular transport systems and with long-term therapy can increase Cmax by 60%. The use of iodine-containing radiocontrast agents for radiological examination while using metformin can lead to the development of lactic acidosis due to functional renal failure.

Cimetidine slows down the elimination of metformin and increases the risk of developing lactic acidosis.

Metformin weakens the effect of indirect anticoagulants (coumarin derivatives).

While using the drug metformin, you should not drink alcohol or ethanol-containing drugs, as this increases the risk of developing lactic acidosis, especially when fasting or following a low-calorie diet.