Classification

There are three degrees of malnutrition in children, each of which is characterized by its own characteristics:

- I degree - 20% of the required body weight is missing, while growth and neuropsychic development are maintained within normal limits;

- II degree - the deficiency is 25–30% of the required indicators, the first signs of growth retardation and neuropsychic disorders appear;

- III degree - weight loss is more than 30% of normal, stunted growth and pathological changes in the neuropsychic sphere become clearly visible.

Read also: Food poisoning in a child

Diagnosis of malnutrition

The diagnosis of malnutrition is based not only on determining the presence of underweight in a child, but also on identifying the immediate cause of the development of this pathological condition. An obligatory stage is an examination of the child by a pediatrician, as well as a conversation with the parents, during which the doctor learns all the necessary anamnestic data. After a thorough physical examination of the child and analysis of the life history and illness, additional laboratory and instrumental tests and consultations with specialized specialists (pediatric endocrinologist, gastroenterologist, etc.) are prescribed.

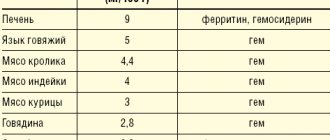

Laboratory diagnostics must necessarily include general clinical tests (general blood and urine tests), coprograms, biochemical blood tests with determination of glucose, total protein (as well as its fractions), liver tests and other indicators.

Of the instrumental diagnostic methods, ultrasound of the abdominal organs, electrocardiography (ECG), and echocardiography (ultrasound of the heart) are mandatory.

If necessary, if indicated, other studies , which help determine the underlying disease against which the malnutrition occurred.

Factors leading to development

The causes accompanying the disease can be external and internal. The first group, characterized by disorders in the body, includes:

- encephalopathy, due to which not only the functioning of the nervous system is disrupted, but also secondary changes occur in the functioning of other organs;

- pathological development of lung tissue, due to which the body does not receive the required amount of oxygen, slowing down its internal processes;

- congenital pathological changes in the functioning of the gastrointestinal tract, leading to insufficient absorption of food;

- surgical operations on the intestines, leading to its shortening;

- diseases of the immune system, leading to the inability to fight infections;

- endocrine changes (most often hypothyroidism or pituitary dwarfism);

- hereditary diseases that disrupt the absorption of certain nutrients (galactosemia, fructosemia, etc.).

The second category includes:

- insufficient nutritional value of breast milk;

- underfeeding;

- the impact of toxic factors on the body;

- frequent infectious infections.

Symptoms

Symptoms of malnutrition in a child depend on the stage of the disease.

At stage I , the doctor can determine the signs by carefully examining the small patient. Pay attention to insufficiently intense staining and decreased skin turgor, lack of fat in the abdominal area.

At stage II, disturbances in motor activity and appetite are evident. The patient's skin becomes flabby, peels, and does not straighten on its own with mild deformities. The layer of subcutaneous fat remains only on the face. Frequent deviations in the functioning of other systems, attacks of tachycardia or too low blood pressure are recorded.

At stage II , a poor reaction to external stimuli is revealed, the face also loses a layer of subcutaneous fat, and muscle atrophy is noted. Characteristic signs are retraction of the eyeballs and the fontanel area. Disturbances in stool and urination appear, and vomiting is common.

Treatment options

Treatment of malnutrition in children begins with the selection of adequate diet therapy. The diet is selected in two stages:

- find out if there is any food intolerance;

- Calculate nutrition for a child with malnutrition.

The calculation is carried out based on the baby’s body weight, his height and the severity of the disease. Meals should be fractional, if necessary, portions are adjusted up or down, so doctor’s supervision over the progress of treatment is necessary.

Diet therapy is accompanied by drug treatment based on the selection of enzymes, vitamins, and hormonal anabolic drugs, if necessary.

Eating disorders in young children

Over the past decades, in the Russian Federation, as well as throughout the world, the number of children with nutritional disorders has been increasing. At the same time, the main efforts of researchers are aimed at studying the problem associated with overweight and obesity. There is a relationship between increased protein intake, accompanied by accelerated weight gain in children in the first year of life, and the subsequent development of metabolic syndrome. Much less attention is paid to children with retarded physical development. At the same time, the nature of malnutrition has changed in many countries. As a rule, it does not arise as a result of a nutritional factor - insufficient nutrition of a healthy child, but as a result of severe, often chronic, diseases leading to increased needs for nutrients or impaired absorption of nutrients [1–3].

There are several terms for insufficient physical development of children. In our country, the term “hypotrophy” is accepted and traditionally used, which is understood as a chronic nutritional disorder characterized by a deficiency of body weight in relation to the height and age of the child. This condition is predominantly observed in young children due to high growth rates and the activity of metabolic processes that require a sufficient supply of nutrients and energy. The pathogenesis of malnutrition is determined by the disease that caused it, but in all cases it includes gradually deepening metabolic disorders with depletion of fat and carbohydrate reserves, increased protein catabolism and a decrease in its synthesis. There is a deficiency of many essential microelements responsible for the implementation of immune functions, optimal growth, and brain development. Therefore, long-term malnutrition is often accompanied by a lag in psychomotor development, delayed speech and cognitive skills and functions, and a high incidence of infectious diseases due to decreased immunity, which in turn aggravates nutritional disorders [3–5].

However, when defining the concept of “hypotrophy”, possible growth retardation (body length), which characterizes the most severe manifestations of nutritional deficiency, is not taken into account.

In 1961, the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Nutrition proposed the term “protein energy malnutrition” (PEM) as an umbrella term for diseases such as marasmus and kwashiorkor. PEM is a nutrition-dependent condition caused by sufficient duration and/or intensity of predominantly protein and/or energy starvation, manifested by a deficiency of body weight and/or height and a complex disruption of the body’s homeostasis in the form of changes in basic metabolic processes, water-electrolyte imbalance, changes body composition, nervous regulation disorders, endocrine imbalance, suppression of the immune system, dysfunction of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and other organs and systems. That is, a pronounced deficiency in the supply of nutrients was assumed. At the same time, insufficient absorption or increased needs of sick children, as well as micronutrient deficiencies, were not taken into account.

Thus, both terms used have certain disadvantages. The most general, in our opinion, unifying term for denoting such conditions may be the term “violation of nutritional status,” which leads to impairment of physical and, in many cases, mental development (deficiency of protein, iron, long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, etc.).

Causes of nutritional status disorders (hypotrophy, PEM)

Physical development disorders can be caused by both exogenous and endogenous factors [6–9]. Exogenous causes are insufficient supply of nutrients due to malnutrition (deficient nutrition) or difficulty eating (as a result of neurological disorders, developmental abnormalities or injuries of the maxillofacial apparatus). Endogenous factors include:

- disorders of digestion, absorption and retention of nutrients;

- increased needs for nutrients and energy (premature babies, congenital heart defects, chronic lung pathology, severe infections accompanied by catabolic stress, etc.);

- hereditary and congenital metabolic diseases.

Domestic pediatricians mainly differentiate malnutrition by the time of occurrence and by body weight deficiency (). There are prenatal (congenital) and postnatal (developed after birth) malnutrition. Prenatal malnutrition is based on disturbances in the intrauterine development of the fetus due to insufficiency of placental circulation, exposure to infectious, hereditary and constitutional characteristics of the mother, as well as unfavorable socio-economic, industrial and environmental factors. There is also the term “intrauterine growth retardation” (IUGR). Newborns with IUGR have a body weight deficit exceeding 2 sigma deviations. IUGR is divided into hypotrophic, hypoplastic, and dysplastic types. With postnatal manifestations, depending on the lack of body weight, malnutrition of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd degrees is distinguished.

Foreign authors use the classification proposed by Waterlow JC with subsequent modifications (

). There are two main forms of PEM: acute, manifested by a predominant loss of body weight and its deficiency in relation to the proper body weight for height, and chronic, manifested not only by a deficiency of body weight, but also by significant growth retardation. Both forms have three degrees of severity: mild, moderate and severe.

The use of different terms creates confusion and complicates statistical calculations. Therefore, during the discussion it is necessary to come to a consensus on the terminology and classification of these conditions. In this article we will mainly use the term generally accepted in our country - “hypotrophy”.

Metabolic changes in nutritional disorders

During the development of malnutrition, all types of metabolism gradually change. In the first stages, glycogen and fat depots are depleted. With continued severe nutritional deficiency, protein breakdown occurs, mainly in muscle tissue. The level of short-lived blood proteins (transthyretin, transferrin, ceruloplasmin, etc.) decreases, then the concentration of albumin and total protein decreases. Disorders of protein metabolism lead to a decrease in immunity due to changes in the synthesis of immunoglobulins, as well as antioxidant activity, accompanied by damage to cell membranes, a decrease in the secretion of transport proteins, intracellular energy deficiency and impaired transport of micronutrients. The activity of enzymes and the secretion of insulin, as well as insulin-like growth factor, decreases, insulin resistance decreases, and the synthesis of fibrinogen and blood clotting factors is disrupted.

The limited supply of protein during malnutrition of degrees I and II leads to increased protein breakdown and increased reutilization of amino acids. Amino acids are actively used for the synthesis of extremely necessary transport, immune, acute-phase and some other proteins, and are also spent on energy needs. With grade III malnutrition, protein breakdown slows down. A moderate slowdown of this process, as well as the reutilization of amino acids, occurs during marasmus, which occurs due to insufficiency of protein and energy. The development of kwashiorkor, which is characterized by a pronounced protein deficiency with a satisfactory intake of carbohydrates, leading to the occurrence of edema, is accompanied by an almost complete cessation of protein breakdown, which, together with a decrease in the activity of amino acid reutilization, leads to a sharp drop in their concentration (including cysteine, a precursor of glutathione) and severe impairment of the synthesizing function of the liver. The resulting oxidative stress leads to the destruction of cell integrity. Therefore, the mortality rate for kwashiorkor is significantly higher than for marasmus. The reasons for various changes in protein metabolism in these diseases remain unknown [10].

With the development of malnutrition, energy metabolism changes from predominantly carbohydrate to lipid. Fat breakdown increases (grade I–II hypotrophy). Non-esterified fatty acids are used as a source of energy. The biosynthesis of fatty acids from cholesterol, which are necessary to maintain the functioning of the digestive system, and corticosteroids, which regulate adaptation processes, increases. In case of severe disorders in children with grade III malnutrition, the body switches to maximum energy saving mode. As a result, the process of fat breakdown slows down significantly, the absorption of non-esterified fatty acids worsens, the concentration of phospholipids and non-esterified cholesterol in the blood decreases, which leads to disruption of the structure and functioning of cell membranes, a decrease in the concentration of corticosteroids and fatty acids [11]. A deficiency of essential fatty acids develops. Changes occurring in cell membranes, combined with the gradually developing decompensation of the antioxidant system and a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity, lead to a decrease in the assimilation of triglycerides in tissues. The liver becomes overloaded with triglycerides and its functioning is disrupted. Therefore, with grade III malnutrition, at the first stage of treatment, the fat content in the diet is limited, as is the use of fat emulsions for parenteral nutrition.

Inadequate nutrition and the resulting stress lead to a sharp increase in cortisol production, which, in conditions of reduced insulin synthesis, increases the cortisol/insulin ratio. This leads to increased catabolic processes, which are aggravated by a decrease in the production of insulin-like growth factor and triiodothyronine. Under conditions of catabolic metabolic processes, energy (glucose) is directed predominantly to the brain, insulin-dependent tissue growth is disrupted, body weight decreases and linear growth slows down.

The changes that occur during malnutrition cannot but affect the digestive system. Atrophy of the intestinal mucosa occurs, which is accompanied by a decrease in enzymatic activity and the production of hydrochloric acid, and the processes of digestion and assimilation of food become difficult. The motility of the gastrointestinal tract is impaired, and local immunity suffers. All these changes lead to intestinal dysbiosis, which further aggravates the digestion process.

Diagnostics

Clinical and laboratory methods are used to identify the presence of nutritional status disorders in children. Anamnesis and clinical examination with assessment of specific symptoms of malnutrition and hypovitaminosis are necessary. Anthropometry is used to calculate the Z-score, the thickness of the skin-fat folds is measured. Somatometric methods are a key way to assess the nutritional status of a child. In this case, it is necessary to have tables comparing weight-height and age indicators and/or a map of the centile distribution of weight and height indicators.

In 2006, the World Health Organization proposed “Standard Growth Charts” for children of all age groups for use in general pediatric practice. These maps present the distribution of children by weight, age, height, weight and height, as well as by body mass index.

When assessing the state of a child’s physical development, the most informative is a comprehensive assessment of body weight and height depending on age. Combined deficiency of body weight and length develops not only with prolonged nutritional deficiency, but also in cases of severe chronic diseases of the child.

In epidemiological studies of the prevalence of malnutrition in children, the Z-score indicator is used, which is the deviation of the values of an individual indicator (body weight, height) from the average value for a given population, divided by the standard deviation of the average value.

Biochemical methods for assessing nutritional status disorders include determining the content of albumin and short-lived proteins (transthyretin, retinol-binding protein, transferrin, etc.). Their concentrations decrease during malnutrition. Another indicator of protein metabolism disorders is alpha1 antitrypsin, an inhibitor of proteolytic enzymes, the level of which increases during protein breakdown.

Immune markers of malnutrition are absolute lymphopenia, a decrease in the CD4+/CD8+ ratio, a delay in hypersensitivity tests (indicators of cellular immunity), as well as a decrease in the level of immunoglobulins, which characterize the state of humoral immunity. These indicators only partially reflect the severity of malnutrition and the degree of restoration of nutritional status, but have important prognostic significance.

Dietary correction of malnutrition

Despite the fact that the main approaches to dietary therapy for malnutrition were developed quite a long time ago - in the 50s–70s, the degree of nutritional load, including protein, in children with varying degrees of malnutrition has not yet been finally determined, and the duration of its use remains controversial, especially in children with severe chronic diseases.

Experimental work and studies involving children in recent years have changed our understanding of optimal nutrition. The proposed relationship between increased nutrition in the first year of life (excess protein intake) and the subsequent development of metabolic syndrome is increasingly supported.

Nutritional disorders during critical periods, which include the entire period of intrauterine development, as well as the first months of a child’s life, lead to persistent changes in metabolism, which increase the risk of developing metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, and allergic diseases.

Back in 1980–1990. Barker DJ first identified the relationship between low birth weight and an increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. There is an assumption that the cause of its occurrence is increased nutrition of low birth weight children, including children with intrauterine malnutrition. This is indeed possible with prolonged overnutrition of children, especially after the first year, when the foundations of eating behavior are formed, which persist throughout life. But, on the other hand, with prolonged nutritional deficiency, metabolic changes occur aimed at maximizing energy conservation, and the result is a decrease in growth rate and lean body mass, with an increase in the fat component (abdominal fat). That is, both insufficient and excess nutrition can lead to the development of metabolic syndrome. However, with a deficiency of nutrients, in addition to this, intelligence also decreases, and osteopenia, anemia and other deficiency conditions that have long-term negative consequences develop [3–5, 12]. Poor nutrition and low physical activity in subsequent years increases the risk of metabolic syndrome.

As studies conducted by Sawaya AL show, quantitative and qualitative optimization of the nutrition of children with delayed physical development resulting from malnutrition allows a return to normal gains in weight and body length, helps normalize body composition, bone density and insulin metabolism in children of any age. age. However, in children under two years of age this process occurs faster [13].

Treatment of children with malnutrition consists of dietary therapy, medication correction and timely provision of psychosocial assistance.

To select dietary treatment tactics you must:

- determine the causes of physical development disorders;

- establish a deficit in body weight and height;

- calculate and evaluate actual nutrition.

Then the qualitative and quantitative composition of the diet is corrected, taking into account the physiological needs of the child, his functional capabilities and the specifics of the pathology.

In our opinion, fundamental differences in approaches to diet therapy exist for malnutrition I–II and malnutrition of the third degree. This is due to differences in the course of metabolic processes, the functioning of the digestive system and the nature of the identified hormonal disorders. In addition, the traditional principles of managing children with malnutrition of degrees I and II are similar and differ only in the calculations of the initial intake of nutrients. In case of malnutrition of the first degree, the amount of nutrients is calculated based on the expected body weight, and in case of malnutrition of the second degree - on the actual one with a gradual transition to the expected one. At the same time, the majority of children with grade II malnutrition (as a rule, these are children with various pathologies) already receive enhanced nutrition, designed for the proper body weight. In such a situation, restricting nutrition is inappropriate, the first phase of calculations is omitted, and nutrition is prescribed in the same way as for children with grade I malnutrition.

Hypotrophy of the first degree develops under the influence of malnutrition, as well as various somatic and infectious diseases. In the first case, it is necessary to establish a general regime, child care, and eliminate feeding defects. Preference when prescribing nutrition should be given to breast milk, and when mixed and artificial feeding - to adapted milk formulas enriched with pro- and prebiotics that have a beneficial effect on the digestive processes and normalization of the composition of the intestinal microflora, nucleotides that contribute to the optimal growth and functioning of the gastrointestinal tract, improve absorption nutrients and optimize the maturation of the child’s immune system, as well as long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs), which influence growth-dependent gene expression, cell growth and the activity of membrane-dependent processes. It is possible to use fermented milk mixtures in an amount of no more than 1/2 of the total feeding volume [14]. Unadapted fermented milk products (kefir, yogurt, etc.) should not be prescribed to children younger than 8–9 months of age. To increase the energy value of the diet and increase the protein quota, timely introduction of complementary foods (porridge, vegetable puree with meat and vegetable oil, cottage cheese) is necessary.

In case of malnutrition that has developed against the background of somatic or infectious pathology, the main food product (breast milk and medicinal formula) is prescribed taking into account the nature of the underlying disease (malabsorption, increased needs, etc.).

In case of first degree malnutrition, calculations and nutritional correction are carried out based on the proper body weight, which consists of body weight at birth and the sum of its normal increases over the life period (

). However, a number of diseases require an increase in the energy value of the diet (bronchopulmonary dysplasia, celiac disease, cystic fibrosis, etc.).

Hypotrophy of the second degree mainly develops with severe congenital or acquired pathology; insufficient nutrition becomes its cause much less often. Dietary correction of grade II nutritional malnutrition is conventionally divided into three periods: the adaptation period (determining food tolerance), the reparation period (intermediate) and the period of enhanced nutrition.

During the adaptation period (duration 2–5 days), nutrition calculations are based on actual body weight (). The number of feedings is increased by 1–2 per day with a corresponding reduction in the volume of each feeding; if necessary, additional fluid is administered (5% glucose solution or saline solutions for oral rehydration). During this period, it is preferable to use breast milk; in case of its deficiency or absence, adapted infant formula enriched with probiotics, oligosaccharides and nucleotides. It is possible to use formulas with a higher protein content, for example, specialized milk formulas for premature and low birth weight babies. If violations of the breakdown/absorption of food ingredients are detected, it is advisable to use medicinal products (for example, low-lactose mixtures for lactase deficiency, mixtures with an increased quota of medium-chain triglycerides for fat malabsorption). If there is no effect, mixtures based on highly hydrolyzed milk protein with medium chain triglycerides should be prescribed [3, 14].

Subsequently, with normal tolerance, a reparation period begins, when the volume of nutrition gradually (over 5–7 days) increases, while the calculation of nutrients is carried out based on the proper body weight. First, the carbohydrate and protein components of the diet are increased, and only lastly the fat component. This becomes possible with the introduction of complementary foods. It is advisable to prescribe industrially produced dairy-free porridges first, which are diluted with breast milk or the formula that the child receives, then pureed meat, cottage cheese, and yolk are introduced. During this period, it is recommended to prescribe enzyme preparations, multivitamin complexes and agents that have a positive effect on metabolic processes (Elcar, Potassium Orotate, Korilip, Limontar, Glycine, etc.).

This is followed by a period of enhanced nutrition, during which the child receives high-calorie nutrition (130–145 kcal/kg/day) in combination with medications that improve the digestion and absorption of food. In cases where II degree malnutrition is caused by a severe course of a chronic disease and the child is already receiving a high-calorie diet at the time of visiting the doctor, a diet revision is carried out. Against the background of drug treatment of the underlying disease and the use of drugs that improve the digestion and absorption of nutrients and agents that have a positive effect on metabolic processes, specialized products with a high content of easily digestible protein and containing medium-chain triglycerides are prescribed.

Gradually, from 4 months of age, complementary feeding products are introduced; preference should be given to industrially produced cereals, for the cultivation of which the specified mixtures are used. Particular attention is paid to sufficient content of meat puree and vegetable oils in diets.

Hypotrophy of the third degree, as well as hypotrophy of the second degree, usually occurs with severe somatic and infectious diseases. In this case, all types of metabolism are sharply disrupted, the child’s condition, as a rule, is very serious, so such children need intensive care, the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition, which requires hospital treatment. Parenteral nutrition in the initial period should be reasonable, balanced and as short as possible due to the risk of developing severe complications. In the first days, amino acid preparations and glucose solutions are used, then fat emulsions are added.

In parallel, parenteral correction of dehydration, acid-base imbalance (ABS) (usually acidosis) and electrolyte disturbances is carried out. The most justified type of enteral nutrition in severe forms of malnutrition is long-term tube feeding, which consists of a continuous slow flow of nutrients into the gastrointestinal tract (stomach, duodenum, jejunum - drip, optimally - using an infusion pump). Constant (or at short intervals) slow introduction of specialized products is absolutely justified, since the energy consumption for digestion and absorption of nutrients under these conditions is much lower than with portioned administration.

With this method of feeding, cavity digestion improves, the absorption capacity of the intestine gradually increases and the motility of the upper gastrointestinal tract is normalized. For enteral nutrition in young children, specialized products should be used. The most justified is the use of mixtures based on highly hydrolyzed milk protein, not containing lactose, enriched with medium chain triglycerides (Alfare, Nutrilon Pepti TSC, Nutrilak Peptidi MCT, Pregestimil) [14].

They ensure maximum absorption of nutrients in conditions of significant inhibition of the digestive and absorption capacity of the digestive tract. It is preferable to have DPFA in the medicinal product, especially docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which helps reduce the activity of the inflammatory process associated with the underlying disease and an adequate immune response. The Scientific Center for Children's Health of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences has accumulated extensive positive experience in the use of the specialized medicinal mixture Alfare, enriched with DHA, in the nutrition of seriously ill children with nutritional disorders.

The energy value of products based on highly hydrolyzed milk protein ranges from 0.66–0.72 kcal/ml, which, when administered one liter, will provide the child with 650–720 kcal/day. If necessary, in the first days the medicinal mixture can be diluted at a concentration of 5–7 g of dry powder per 100 ml of water (5–7% solution). Next, the concentration of the mixture is gradually increased to 13.5% (physiological), and if well tolerated - to 15%. The missing calories, nutrients and electrolytes during the period of use of the mixture in low concentrations are compensated by parenteral nutrition.

The duration of the period of constant enteral tube feeding varies from several days to several weeks, depending on the severity of food intolerance disorders (anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea). During this adaptation period, the calorie content of the diet is gradually increased to 120 kcal per kg of actual weight and a slow transition is made to portioned administration of the nutritional mixture - 10 times, and then 7-8 times during the day, maintaining and uniformly distributing the achieved volume. For this purpose, when switching to fractional meals, you can first leave a constant infusion at night until the caloric content of portioned meals does not exceed 75% of the daily intake.

During the reparation period, protein, carbohydrate and then fat components of nutrition are corrected, nutrients are calculated based on the proper body weight, which leads to an increase in the energy value of the diet (). High-calorie complementary foods are gradually introduced into the child's diet, and it is possible to introduce adapted fermented milk formulas. With good tolerance of the prescribed diet at the stage of enhanced nutrition, the calorie content increases to 130–145 kcal/kg/day per proper body weight, with an increased content of nutrients, but not more than: protein - 5 g/kg/day, fat - 6.5 g/day kg/day, carbohydrates - 14–16 g/kg/day. The average duration of the enhanced nutrition stage is 1.5–2 months. The main indicator of the adequacy of diet therapy is weight gain. An increase is considered optimal if it exceeds 10 g/kg/day, average - 5-10 g/kg/day and low - less than 5 g/kg/day. Currently, the cause of the development of grade III malnutrition in children, as a rule, is severe chronic somatic pathology, and not malnutrition, therefore timely diagnosis and treatment of a cause-significant disease are a fundamental factor in the prevention and treatment of this condition.

Drug therapy for stage III malnutrition

In addition to drug (parenteral) correction of dehydration and electrolyte disturbances, in the acute period it is necessary to remember the need for timely diagnosis of possible adrenal insufficiency. Starting from the repair period, enzyme replacement therapy with pancreatic preparations is advisable. Preference is given to microencapsulated drugs. In case of intestinal dysbiosis, biological products are prescribed during antibacterial therapy. The use of anabolic agents is carried out with caution, since in conditions of nutritional deficiency their use can cause profound disturbances in protein and other types of metabolism, inhibition of parietal digestive enzymes. The use of vitamin therapy for stimulating and replacement purposes is indicated. At the first stages of treatment, parenteral administration of vitamin preparations is advisable. Treatment of rickets and iron deficiency anemia is carried out starting from the reparation period. Indications for stimulating and immunotherapy are determined individually. During periods of adaptation and repair, preference should be given to passive immunotherapy (immunoglobulins). During the period of convalescence, nonspecific immunostimulants may be prescribed.

Literature

- Kleiman: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 18th ed., 2007, Chapter 43.

- Sermet-Gauelus I., Poisson-Salomon AS, Colomb V. et al. Simple pediatric nutritional risk score to identify children at risk of malnutrition // AJCN. 2000. V. 72. R. 64–70.

- National program for optimizing the feeding of children in the first year of life in the Russian Federation. Ed. A. A. Baranova, V. A. Tutelyan. M., 2010, 68 p.

- Baby food. A guide for doctors. Ed. V. A. Tutelyan, I. Ya. Konya. M.: MIA, 2009. 952 p.

- Clinical dietetics of childhood. A guide for doctors. Ed. T. E. Borovik, K. S. Ladodo. M.: Medicine, 2008. 606 p.

- Diet therapy for malabsorption syndrome in young children. A manual for doctors. Ed. A. A. Baranova, T. E. Borovik. M., 2006. 51 p.

- Diet therapy in the complex treatment of cystic fibrosis in children. A manual for doctors. Ed. A. A. Baranova, T. E. Borovik. M., 2005. 92 p.

- Kashirskaya N. Yu., Kapranov N. I., Roslavtseva E. A. et al. Issues of nutrition in cystic fibrosis // Pulmonology. 2006. pp. 17–21.

- Sinaasappel M., Stern M., Littlewood J. et al. Nutrition in patients with cystic fibrosis: a European Consecsus // Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 2002. V. 1. R. 51–75.

- Jahoor F., Badaloo A., Reid M. et al. Protein metabolism in severe childhood malnutrition // Ann Trop Paediatr. 2008, 28 (2), p. 87–101.

- Neudakhin E.V. Clinical, metabolic and genetic aspects of malnutrition in young children: Abstract of thesis. diss. doc. honey. Sci. M., 1992.

- Bhutta ZA Micronutrient needs of malnourished children // Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2008. V. 11, No. 3. P. 309–314.

- Sawaya AL, Martins PA, Martins VJB et al. Malnutrition, long term health and the effect of nutritional recovery // Nestle Nutrition Institute. 2009, 63, p. 95–108.

- Catalog “Specialized food products for children with various pathologies.” Ed. T. E. Borovik, K. S. Ladodo, V. A. Skvortsova. M., 2010. 231 p.

V. A. Skvortsova *, Doctor of Medical Sciences T. E. Borovik *, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor O. K. Netrebenko **, Doctor of Medical Sciences * Scientific Center for Children of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, ** Russian State Medical University , Moscow

Contact information for authors for correspondence: [email protected]