Therapist

Berezhko

Olga Igorevna

35 years of experience

General practitioner of the highest category, member of the Russian Scientific Medical Society of Therapists

Make an appointment

Vasculitis is a group of vascular diseases that are characterized by the development of an inflammatory process and subsequent necrosis of the vascular walls. The disease is also called arteritis or angiitis. As the disease progresses, a significant deterioration in blood circulation occurs. Pathology can affect arteries, veins, capillaries, venules and arterioles.

What is vasculitis?

Vasculitis is a group of diseases characterized by the development of inflammation of the walls of blood vessels. This inflammation begins due to an impaired immune response. The cause may be a past infection or allergy. Inflammation can affect small, medium, and large vessels. Because of it, blood circulation and blood supply to individual organs are disrupted, which can cause complications. Without treatment of vasculitis, necrosis of the vessel walls (death of their tissue), bleeding, and ischemia (impaired blood flow) begin. Both children and adults can get vasculitis. The disease can be primary (when inflammation of the walls of blood vessels is the only manifestation without an apparent cause) or secondary. With secondary vasculitis, the walls of blood vessels become inflamed due to other diseases (infectious, oncological, rheumatic).

Types and classification of vasculitis

Vasculitis is divided into types:

- primary;

- secondary;

- systemic.

In the first case, we are talking about an independent and still just beginning disease. The second type may appear with other pathologies, for example, tumors. It can also occur as a reaction to an infection. Systemic vasculitis can occur in different ways. It leads to inflammation of blood vessels and damage to their walls, and tissue necrosis cannot be ruled out. Without proper treatment, complications usually occur, including death.

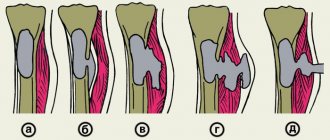

Based on the caliber of the affected vessels, a classification of vasculitis was identified. It may be in the form:

- arteritis (affects large vessels);

- phlebitis (affects the walls of the veins);

- arteriolitis (inflames the arteries and arterioles);

- capillaritis (affects capillaries).

Also included in a separate category is vasculopathy, which is characterized by the absence of clear signs of inflammation and infiltration of the vascular walls.

The degree of vascular damage can be mild, moderate and severe.

Pathogenesis of vasculitis

Vasculitis develops due to a failure of immune mechanisms, but the exact causes of the disease have not been identified. The main hypothesis assumes that the nature of the disease is multi-etiological, associated with many factors. These include:

- acute or chronic bacterial or viral infections;

- allergy. A severe allergic reaction to drug components or food can cause immune failure;

- complication of vaccination. If after vaccination the immune response is impaired, vasculitis may occur. Such complications are very rare;

- severe or prolonged effects of stress, hypothermia or overheating, injuries.

Under the influence of these factors, the production of pathogenic immune complexes begins. Normally, they attack the pathogen, but due to an immune failure, the attack is directed at the body’s cells. Immune complexes attach to the walls of blood vessels, damage them and provoke inflammation.

Figure 1. The difference between a healthy vessel and one affected by vasculitis. Source: sl.smithhealthcentre.com

Urticarial vasculitis: a modern approach to diagnosis and treatment

Urticarial vasculitis/angiitis (UV) is a skin disease characterized by the appearance of blisters with the histological features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis, persisting for more than 24 hours and often resolving with residual effects [1]. The exact prevalence of the disease in Russia and in the world is unknown [2]. Among patients with chronic urticaria, the incidence of HC is 5–20% [3–6]. The pathogenesis of the disease is mediated by the formation and deposition of immune complexes in the walls of blood vessels, activation of the complement system and degranulation of mast cells due to the action of anaphylotoxins C3a and C5a. There are normocomplementary and hypocomplementary forms of HF, as well as a rare syndrome of hypocomplementary HF, which is regarded as a variant of systemic lupus erythematosus [2, 7]. In patients with hypocomplementemia, the disease is usually more severe [8]. All forms of HF, especially hypocomplementary ones, can be accompanied by systemic symptoms (for example, angioedema, pain in the abdomen, joints and chest, uveitis, Raynaud's phenomenon, symptoms resulting from damage to the lungs and kidneys, etc.) [7, 9].

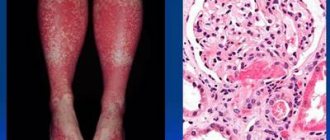

Clinical manifestations

The classic manifestations of HS include blisters (Fig. 1), which are accompanied by burning, pain, tension and, rarely, itching and persist for more than 24 hours (usually 3-5 days, which can be confirmed by circling the rash with a pen or marker and follow-up ). Angioedema (corresponding to the involvement of deep vessels of the skin) occurs in approximately 42% of patients [10], more often in patients with hypocomplementary HF syndrome [11]. Giant urticaria (> 10 cm) appear less frequently than in urticaria.

The rashes are localized on any areas of the body, but more often on areas of the skin subject to pressure. When resolved, they leave behind residual hyperpigmentation, which is better determined by diascopy or dermatoscopy.

Systemic symptoms include fever, malaise, and myalgia. Certain organs may be involved: lymph nodes, liver, spleen, kidneys, gastrointestinal and respiratory tracts, eyes, central nervous system, peripheral nerves and heart (Table).

Damage to joints in HF is more common than damage to other organs; appears in half of patients with HF [10] mainly in the form of migrating and transient peripheral arthralgia in the area of any joints, in 50% of patients with hypocomplementary HF syndrome [15] - in the form of severe arthritis, which is not typical for normocomplementary HF. Renal involvement usually manifests as proteinuria and microscopic hematuria, defined as glomerulonephritis and interstitial nephritis, and occurs in 20–30% of patients with hypocomplementemia [10]. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchial asthma occur in 17–20% of patients with hypocomplementary HF syndrome and in 5% with normocomplementary HF [10]. Possible gastrointestinal symptoms include nausea, abdominal pain, vomiting and diarrhea, which occur in 17–30% of patients with HF [15]. Ophthalmological complications occur in 10% of patients with HF and in 30% of patients with hypocomplementary HF syndrome. As a rule, this is conjunctivitis, episcleritis, iritis or uveitis [16].

Diagnostics

The examination of patients with HF consists of a history, physical examination, laboratory tests and additional consultations with specialists if necessary (rheumatologist, nephrologist, pulmonologist, cardiologist, ophthalmologist and neurologist). It is important to identify systemic symptoms. To do this, for example, if damage to the respiratory tract is suspected, a chest x-ray, pulmonary function tests and/or bronchoalveolar lavage are performed.

Laboratory tests may include measuring antinuclear antibodies, complement components, and cryoglobulins in the blood, as well as a complete blood count and kidney function tests. ESR is often elevated, but does not serve as a specific indicator and is not associated with the severity of HF or the presence of systemic involvement. Hypocomplementemia, as mentioned earlier, is an important marker of systemic disease and a high likelihood of complications.

Optimal confirmation of EF based on serum complement component measurements requires determination of C1q, C3, C4, and CH50 levels 2 or 3 times over several months of follow-up [17]. Detection of anti-C1q can help in the diagnostic search and confirm the diagnosis of hypocomplementary HC.

Cryoglobulinemia is the most well-known and studied syndrome in some patients with hepatitis C and HC [18]. Cryoglobulins are immunoglobulins that precipitate at temperatures below 37 °C and are responsible for the development of systemic vasculitis, characterized by the deposition of immune complexes in small and medium-sized blood vessels [18]. These proteins are detected in 50% of HCV-infected individuals, although symptoms associated with cryoglobulinemia are detected in less than 15% of patients [19] and include HF as well as peripheral neuropathy [20]. Treatment is aimed at the underlying HCV infection.

In most cases of HF, the cause of the disease is not determined. Normocomplementary HF acts as an idiopathic disease in many patients, while in others it is associated with monoclonal gammopathy, neoplasia, and sensitivity to ultraviolet radiation or cold [17].

When collecting an anamnesis, it is necessary to clarify the duration of preservation of individual elements, the presence of pain or burning in the area of the rash (itching with urticaria is less common than with chronic urticaria), the presence of residual effects (for example, hyperpigmentation) and associated symptoms. For differential diagnosis and confirmation of diagnosis, a skin biopsy [1] and referral of the patient for consultation with related specialists may be required.

Skin biopsy is the “gold standard” for diagnosing UV. Skin biopsies stained with hematoxylin and eosin usually show the characteristic histopathological features of vasculitis, which include most of the features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis:

- damage and swelling of endothelial cells, destruction or occlusion of the vascular wall;

- release of red blood cells from the vascular bed into the surrounding tissues (extravasation), leukoclasia or karyorrhexis (disintegration of the nuclei of granular leukocytes, leading to the formation of nuclear “dust”), fibrin deposition in and around the vessels, fibrinoid necrosis of venules;

- perivascular infiltration consisting mainly of neutrophils, although in “old” lesions leukocytes and eosinophils may dominate. Sometimes an increase in the number of TCs is observed.

Treatment

HC treatment is selected depending on the presence/absence of systemic symptoms, the extent and severity of the skin process and the previous response to therapy. The goal of therapy is to achieve long-term control using minimally toxic doses of drugs. There is no single standardized approach to treating the disease yet. We tried to systematize the treatment data given below into a single algorithm for practical use (Fig. 2).

Symptomatic therapy

In patients with HC with isolated skin lesions, 1st and 2nd generation antihistamines (especially with severe itching) [13, 15] and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be effective. The main purpose of the latter is to relieve joint pain (effective in no more than 50% of cases). In some patients, NSAIDs lead to exacerbation of heart failure [10]. It is possible to use ibuprofen up to 800 mg 3 or 4 times a day, naproxen 500 mg 2 times a day or indomethacin 25 mg 3 times a day, increasing the dose as needed to a maximum of 50 mg 4 times a day. Taking NSAIDs can cause erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastrointestinal tract and headaches.

Mild to moderate urticarial vasculitis

For the initial treatment of patients with mild or moderate HC in the absence of systemic symptoms and life-threatening manifestations of the disease (for example, kidney and lung damage), as well as in the ineffectiveness of treatment with antihistamines and NSAIDs, glucocorticosteroids (GCS) are used in monotherapy or in combination with dapsone or colchicine . The dose of corticosteroids varies depending on the severity of the heart attack. It is recommended to begin treatment with 0.5–1 mg/kg per day (with a possible dose increase to 1.5 mg/kg per day) with an assessment of response to treatment after 1 week. The effect of therapy in most cases is observed already on days 1–2 of therapy. Once disease control is achieved, the dose of corticosteroids should be gradually reduced over several weeks to the minimally effective dose to maintain CV control.

With long-term therapy with GCS (more than 2–3 months), there is a risk of side effects, which necessitates the addition of steroid-sparing agents to reduce the dose of GCS [10], such as dapsone. The latter has been successfully used as monotherapy or in combination with GCS at a dose of 50–100 mg per day for the treatment of skin processes in HF and hypocomplementary HF syndrome [11, 21, 22]. Side effects of dapsone include headache, non-hemolytic anemia and agranulocytosis, which requires evaluation of a complete blood count during treatment. In patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, the use of the drug can cause severe hemolysis. In such patients, enzyme levels should be measured before initiating dapsone therapy [23].

As an alternative to dapsone and when its use is contraindicated, colchicine is used at an initial dose of 0.5–0.6 mg per day orally. If there is no effect within several weeks, the dose of colchicine can be increased to 1.5–1.8 mg per day. After starting treatment, it is necessary to evaluate the results of a complete blood count due to the possible development of cytopenias associated with the use of the drug [23].

Severe urticarial vasculitis

In patients with severe HF and refractory, systemic and/or life-threatening symptoms, GCS are used in combination with other drugs (in order of preference): mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, azathioprine and cyclosporine. Cyclophosphamide is rarely prescribed due to potential toxicity and lack of effectiveness. Over the past few years, there has been increasing evidence supporting the use of biological agents: rituximab, anakinra and canakinumab [2, 24–26].

Mycophenolate mofetil has been effective in the treatment of hypocomplementary HF syndrome as maintenance therapy after disease control has been achieved with corticosteroids and cyclophosphamide [24]. Recommended dosage: 0.5–1 g twice daily.

Methotrexate was useful as a steroid-sparing agent in one case [25] and caused exacerbation of HF in another [27].

Azathioprine was effectively used at a starting dose of 1 mg/kg per day in combination with prednisolone for HF with kidney and skin damage [28, 29]. If there is no effect within several weeks, the dose may be increased to the maximum recommended (2.5 mg/kg per day).

Cyclosporine A has been effective in hypocomplementary HF syndrome, especially in the renal and pulmonary complications of the syndrome [30], and also as a steroid-sparing agent [31]. The initial dose of the drug is 2–2.5 mg/kg per day. If there is no effect within several weeks, the dose can be increased to 5 mg/kg per day. The drug is nephrotoxic and may cause increased blood pressure.

Rituximab has been used in several patients with severe HF with varying efficacy [26, 32]. Anakinra was effective in patients with HF that was poorly responsive to other therapies [33]. Canakinumab was prescribed to 10 patients with HC, all of whom showed a marked improvement in the course of the disease, a decrease in the level of inflammatory markers and the absence of severe side effects [34].

Interferon A was effective both in monotherapy and in combination with ribavirin when CV was combined with hepatitis C or A [14, 35]. The effectiveness of other drugs, such as cyclophosphamide, intravenous immunoglobulin and reserpine, has been poorly studied and is shown only in isolated clinical cases [36–38].

Conclusion

HF has a chronic and unpredictable course with an average duration of 3–4 years, and in some cases up to 25 years [39]. In one study, 40% of patients experienced complete remission of the disease within 1 year [15]. Mortality is low if there are no renal or pulmonary complications. When a group of patients was observed for 12 years, most of them did not experience the development of UV-related diseases (oncological, connective tissue, etc.). In isolated cases, the evolution of UD into systemic lupus erythematosus [12, 40] and Sjögren's syndrome [41] has been reported. When a disease that has become a possible cause of vasculitis is identified, the course and prognosis of vasculitis depend on the treatment of the underlying pathology. Fatal outcomes in patients with HF can include laryngeal edema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, respiratory failure, sepsis, renal failure and myocardial infarction [15].

There is a need for well-designed randomized placebo-controlled studies to better understand the etiology and pathogenesis of the disease, clarify the course and prognosis of different forms of HF, as well as study the effectiveness and safety of existing agents and search for new highly effective therapy.

Literature

- Zuberbier T., Aberer W., Asero R., Bindslev-Jensen C., Brzoza Z., Canonica GW, Church MK, Ensina LF, Gimenez-Arnau A., Godse K., Goncalo M., Grattan C., Hebert J., Hide M., Kaplan A., Kapp A., Abdul Latiff AH, Mathelier-Fusade P., Metz M., Nast A., Saini SS, Sanchez-Borges M., Schmid-Grendelmeier P., Simons FE , Staubach P., Sussman G., Toubi E., Vena GA, Wedi B., Zhu XJ, Maurer M. The EAACI/GA (2) LEN/EDF/WAO Guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis, and management of urticaria: the 2013 revision and update // Allergy. 2014. T. 69. No. 7. pp. 868–887.

- Kolkhir P.V., Olisova O.Yu., Kochergin N.G. Syndrome of hypocomplementary urticarial vasculitis at the onset of systemic lupus erythematosus // Bulletin of Dermatology and Venereology. 2013. No. 2. P. 53–61.

- Zuberbier T., Henz BM, Fiebiger E., Maurer D., Stingl G. Anti-FcepsilonRIalpha serum autoantibodies in different subtypes of urticaria // Allergy. 2000. T. 55. No. 10. P. 951–954.

- Natbony SF, Phillips ME, Elias JM, Godfrey HP, Kaplan AP Histologic studies of chronic idiopathic urticaria // J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1983. T. 71. No. 2. P. 177–183.

- Monroe EW Urticarial vasculitis: an updated review // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981. T. 5. No. 1. P. 88–95.

- Warin RP Urticarial vasculitis // Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983. T. 286. No. 6382. P. 1919–1920.

- Saigal K., Valencia IC, Cohen J., Kerdel FA Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis with angioedema, a rare presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus: rapid response to rituximab // J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003. T. 49. No. 5 Suppl. pp. S283–285.

- Davis MD, Daoud MS, Kirby B., Gibson LE, Rogers RS, 3rd. Clinicopathologic correlation of hypocomplementemic and normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998. T. 38. No. 6. Pt 1. P. 899–905.

- Jachiet M., Flageul B., Deroux A., Le Quellec A., Maurier F., Cordoliani F., Godmer P., Abasq C., Astudillo L., Belenotti P., Bessis D., Bigot A., Doutre MS, Ebbo M., Guichard I., Hachulla E., Heron E., Jeudy G., Jourde-Chiche N., Jullien D., Lavigne C., Machet L., Macher MA, Martel C., Melboucy-Belkhir S., Morice C., Petit A., Simorre B., Zenone T., Bouillet L., Bagot M., Fremeaux-Bacchi V., Guillevin L., Mouthon L., Dupin N., Aractingi S., Terrier B. The clinical spectrum and therapeutic management of hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis: data from a French national study of fifty-seven patients // Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015. T. 67. No. 2. P. 527–534.

- Mehregan DR, Hall MJ, Gibson LE Urticarial vasculitis: a histopathologic and clinical review of 72 cases // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992. T. 26. No. 3. Pt 2. P. 441–448.

- Wisnieski JJ, Baer AN, Christensen J, Cupps TR, Flagg DN, Jones JV, Katzenstein PL, McFadden ER, McMillen JJ, Pick MA et al. Hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome. Clinical and serologic findings in 18 patients // Medicine (Baltimore). 1995. T. 74. No. 1. P. 24–41.

- Bisaccia E., Adamo V., Rozan SW Urticarial vasculitis progressing to systemic lupus erythematosus // Arch Dermatol. 1988. T. 124. No. 7. P. 1088–1090.

- Callen JP, Kalbfleisch S. Urticarial vasculitis: a report of nine cases and review of the literature // Br J Dermatol. 1982. T. 107. No. 1. P. 87–93.

- Hamid S., Cruz PD, Jr., Lee WM Urticarial vasculitis caused by hepatitis C virus infection: response to interferon alfa therapy // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998. T. 39. No. 2. Pt 1. P. 278–280.

- Sanchez NP, Winkelmann RK, Schroeter AL, Dicken CH The clinical and histopathologic spectrum of urticarial vasculitis: study of forty cases // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1982. T. 7. No. 5. P. 599–605.

- Davis MD, Brewer JD Urticarial vasculitis and hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome // Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004. T. 24. No. 2. P. 183–213.

- Wisnieski JJ Urticarial vasculitis // Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000. T. 12. No. 1. P. 24–31.

- Misiani R., Bellavita P., Fenili D., Borelli G., Marchesi D., Massazza M., Vendramin G., Comotti B., Tanzi E., Scudeller G. et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia // Ann Intern Med. 1992. T. 117. No. 7. P. 573–577.

- Pawlotsky JM, Roudot-Thoraval F., Simmonds P., Mellor J., Ben Yahia MB, Andre C., Voisin MC, Intrator L., Zafrani ES, Duval J., Dhumeaux D. Extrahepatic immunologic manifestations in chronic hepatitis C and hepatitis C virus serotypes // Ann Intern Med. 1995. T. 122. No. 3. P. 169–173.

- Ferri C., La Civita L., Cirafisi C., Siciliano G., Longombardo G., Bombardieri S., Rossi B. Peripheral neuropathy in mixed cryoglobulinemia: clinical and electrophysiologic investigations // J Rheumatol. 1992. T. 19. No. 6. P. 889–895.

- Eiser AR, Singh P., Shanies HM Sustained dapsone-induced remission of hypocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis - a case report // Angiology. 1997. T. 48. No. 11. P. 1019–1022.

- Muramatsu C., Tanabe E. Urticarial vasculitis: response to dapsone and colchicine // J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985. T. 13. No. 6. P. 1055.

- Venzor J., Lee WL, Huston DP Urticarial vasculitis // Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2002. T. 23. No. 2. P. 201–216.

- Worm M., Sterry W., Kolde G. Mycophenolate mofetil is effective for maintenance therapy of hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis // Br J Dermatol. 2000. T. 143. No. 6. P. 1324.

- Stack PS Methotrexate for urticarial vasculitis // Ann Allergy. 1994. T. 72. No. 1. P. 36–38.

- Mukhtyar C., Misbah S., Wilkinson J., Wordsworth P. Refractory urticarial vasculitis responsive to anti-B-cell therapy // Br J Dermatol. 2009. T. 160. No. 2. P. 470–472.

- Borcea A., Greaves MW Methotrexate-induced exacerbation of urticarial vasculitis: an unusual adverse reaction // Br J Dermatol. 2000. T. 143. No. 1. P. 203–204.

- Moorthy AV, Pringle D. Urticaria, vasculitis, hypocomplementemia, and immune-complex glomerulonephritis // Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1982. T. 106. No. 2. P. 68–70.

- Ramirez G., Saba SR, Espinoza L. Hypocomplementemic vasculitis and renal involvement // Nephron. 1987. T. 45. No. 2. P. 147–150.

- Soma J., Sato H., Ito S., Saito T. Nephrotic syndrome associated with hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome: successful treatment with cyclosporin A // Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999. T. 14. No. 7. P. 1753–1757.

- Renard M., Wouters C., Proesmans W. Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis in a boy with hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis // Eur J Pediatr. 1998. T. 157. No. 3. P. 243–245.

- Mallipeddi R., Grattan CE Lack of response to severe steroid-dependent chronic urticaria to rituximab // Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007. T. 32. No. 3. P. 333–334.

- Botsios C., Sfriso P., Punzi L., Todesco S. Non-complementaemic urticarial vasculitis: successful treatment with the IL-1 receptor antagonist, anakinra // Scand J Rheumatol. 2007. T. 36. No. 3. P. 236–237.

- Krause K., Mahamed A., Weller K., Metz M., Zuberbier T., Maurer M. Efficacy and safety of canakinumab in urticarial vasculitis: an open-label study // J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013. T. 132. No. 3. P. 751–754, e755.

- Matteson EL Interferon alpha 2 a therapy for urticarial vasculitis with angioedema apparently following hepatitis A infection // J Rheumatol. 1996. T. 23. No. 2. P. 382–384.

- Worm M., Muche M., Schulze P., Sterry W., Kolde G. Hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis: successful treatment with cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone pulse therapy // Br J Dermatol. 1998. T. 139. No. 4. P. 704–707.

- Berkman SA, Lee ML, Gale RP Clinical uses of intravenous immunoglobulins // Ann Intern Med. 1990. T. 112. No. 4. P. 278–292.

- Demitsu T., Yoneda K., Iida E., Takada M., Azuma R., Umemoto N., Hiratsuka Y., Yamada T., Kakurai M. Urticarial vasculitis with haemorrhagic vesicles successfully treated with reserpine // J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008. T. 22. No. 8. pp. 1006–1008.

- Soter NA Chronic urticaria as a manifestation of necrotizing venulitis // N Engl J Med. 1977. T. 296. No. 25. P. 1440–1442.

- Soylu A., Kavukcu S., Uzuner N., Olgac N., Karaman O., Ozer E. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting with normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis in a 4-year-old girl // Pediatr Int. 2001. T. 43. No. 4. P. 420–422.

- Aboobaker J., Greaves MW Urticarial vasculitis // Clin Exp Dermatol. 1986. T. 11. No. 5. P. 436–444.

P. V. Kolhir1, Candidate of Medical Sciences O. Yu. Olisova, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor

GBOU VPO First Moscow State Medical University named after. I. M. Sechenova Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow

1 Contact information

Classification

Vasculitis is a large group of diseases, and two classifications are used for them. The first is by etiology - it takes into account the reasons for which the disease appears. The second is by localization, taking into account which vessels are affected.

By etiology

This classification takes into account the causes of vasculitis:

- primary. Inflammation of the walls of blood vessels is not associated with other diseases, is not their manifestation and develops as an independent disease. The exact causes of primary vasculitis have not been established, but it is known that hereditary predisposition plays an important role;

- secondary. The walls of blood vessels become inflamed due to other diseases, inflammation is one of their manifestations.

There are several types of secondary vasculitis based on the underlying disease or condition that caused inflammation of the vessel walls:

- hepatitis B and C viruses;

- syphilis;

- oncological diseases;

- reaction to taking medications.

By localization

Division by localization takes into account which vessels are affected by vasculitis and where they are located. This determines the clinical picture, treatment approaches, prognosis and possible complications. The walls of small, medium and large blood vessels can become inflamed; inflammation can affect blood vessels of different sizes or vessels of individual organs.

Vasculitis of large blood vessels

When the walls of large blood vessels become inflamed, there are several common symptoms. These are large deviations from the norm when blood pressure changes and anomalies in the propagation of pulse waves. With each such wave after the heart contracts, the pressure in the arteries increases. If the wave is asymmetrical or absent on the arms or legs, this may be a sign of vasculitis. The disease is also indicated by the development of ischemia (decreased blood flow in a particular area), intermittent claudication (pain that occurs when walking and goes away after rest). Each type of vasculitis of large blood vessels has its own additional symptoms.

Giant cell arteritis. Inflammation affects the thoracic aorta, as well as the large arteries running from it to the neck, and the extracranial section of the carotid artery. Polymyalgia rheumatica is often the cause of giant cell arteritis. Symptoms include: headaches, blurred vision, fever, weight loss, fatigue, and general malaise.

Takayasu arteritis. Inflammation of the walls of the aorta and its branches, the walls of the pulmonary arteries, most often develops in young women. The first signs of the disease are weakness, spastic pain in the limbs, periodic visual disturbances, hypertension, differences in pulse or blood pressure values on different legs or arms or on an arm and leg on the same side.

Vasculitis of medium-sized vessels

The general manifestation is symptoms of infarction of the tissues of the affected organs: their necrosis occurs due to insufficient blood supply. On the skin this is manifested by the formation of nodules, ulcers, and livedo reticularis (discoloration). With a muscle tissue infarction, severe pain appears. It is possible to develop multiple neuropathy (damage to several nerves), kidney damage (increased pressure in the renal arteries), and mesenteric ischemia, which disrupts blood flow in the intestinal vessels. The exact symptoms depend on where exactly the affected vessels are located.

Cutaneous vasculitis. It affects the vessels of the subcutaneous tissue, which is why ulcers, purpura (hemorrhages in or under the skin, look like scatterings of small red dots), petechiae (bright red rash) appear on the skin.

Polyarteritis nodosa. With this disease, the walls of the muscle arteries become inflamed, causing secondary tissue ischemia to develop. With nodular arteritis, damage to the skin, kidneys, peripheral nerves, gastrointestinal tract, and any other organs is possible. Lung damage is not typical. First, general symptoms appear: fatigue, fever. Other manifestations depend on which organ is affected.

Vasculitis of small vessels

When the walls of small vessels become inflamed, symptoms of tissue infarction develop in the affected area. Often these manifestations are similar to the symptoms of vasculitis of medium vessels.

Cryoglobulinemic vasculitis. It is systemic and affects mainly small vessels. Blood serum analysis reveals cryoglobulins. Symptoms are varied and are determined by the location of the inflammation. Damage to the kidneys and peripheral nervous system often develops, and vascular purpura appears. General manifestations are weakness, slight increase in temperature, fatigue. In 90% of cases, purpura appears, most often it forms on the skin of the legs. When the kidneys are damaged, peripheral edema and increased pressure in the renal artery develop. It is also possible to experience muscle and joint pain and enlarged lymph nodes.

Wegener's granulomatosis. The lesion can affect any organs, but most often it is the respiratory organs or kidneys. If the respiratory organs are affected, the first symptoms are cough and runny nose, after which swelling develops, increased pressure, and symptoms of damage to several organs at once appear.

Hemorrhagic vasculitis. More often children get it. There are four forms of the disease: cutaneous (cutaneous-articular), abdominal (with damage to the digestive organs), renal, mixed. Accordingly, characteristic symptoms are identified, including palpable purpura, abdominal or joint pain, renal syndrome, vomiting, and nausea.

Microscopic polyangiitis. A rare disease that most often affects the kidneys. In about a third of cases, additional purpura appears on the skin. Possible damage to the respiratory system with the rapid development of shortness of breath, hemoptysis, and anemia. If alveolar bleeding develops against this background, the patient needs emergency help. Abdominal pain, vomiting and nausea, and damage to the nervous system are also possible.

Vasculitides that can affect blood vessels of varying sizes

Behçet's disease. Inflammation develops on the walls of small or medium-sized vessels. Symptoms depend on location. The disease can affect the lungs, kidneys, stomach, and brain. A peculiarity is the frequent appearance of ulcers on the mucous membranes of the mouth, in the genital area, and other mucous membranes.

Cogan's syndrome. A rare disease in which blood vessels of different sizes become inflamed. The disease is often accompanied by fever, joint pain, neurological disorders, decreased vision, hearing loss (may be irreversible).

Systemic vasculitis

This group includes vasculitis associated with systemic diseases:

- systemic lupus erythematosus. The immune system begins to produce antibodies that damage healthy cells. Because of this, the walls of blood vessels become inflamed and lupus vasculitis develops;

- rheumatoid arthritis. This is a systemic inflammatory disease affecting small joints. May be accompanied by rheumatoid vasculitis;

- sarcoidosis The disease is accompanied by the formation of granulomas (nodules) in inflamed tissues. Foci of inflammation in sarcoidosis form in the lymph nodes, lungs, liver, spleen, skin, and bones. Sarcoidosis may be accompanied by sarcoid vasculitis.

Vasculitis of individual organs

Inflammation of blood vessels can affect only one, separate organ. Such diseases include:

- cutaneous vasculitis. Affects small and medium-sized vessels in the skin and subcutaneous tissue, manifested by the formation of ulcers, purpura, petechiae;

- cutaneous leukocytclastic angiitis. Inflammation of blood vessels in the skin is isolated and is not accompanied by systemic vasculitis or other associated conditions;

- primary angiitis of the central nervous system. It affects the vessels of the spinal cord, brain, and pia mater. There are no signs of systemic inflammation;

- isolated aortitis. A form of vasculitis with limited localization of inflammation of the vessel walls.

Classification of systemic vasculitis (EULAR 2009)

Predominant damage to small-caliber vessels:

- Henoch-Schönlein purpura

- Essential cryoglobulinemic vasculitis

- Microscopic polyangiitis

Predominant damage to small and medium-sized vessels:

- Wegener's granulomatosis (since 2011 granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's)

- Churg-Strauss vasculitis

Predominant damage to medium-sized vessels:

- Polyarteritis nodosa

- Kawasaki disease

Predominant damage to large vessels:

- Temporal giant cell arteritis

- Takayasu arteritis

Combined conditions:

- Behçet's disease

- Thromboangiitis obliterans

Causes

Inflammation of the walls of blood vessels begins due to autoimmune disorders, in which antibodies are produced against the cells of one’s own body. The exact causes of primary vasculitis have not been established. Secondary vasculitis develops against the background of infectious or oncological diseases, as a rare complication of vaccination, after overheating or hypothermia, or sunburn.

Other possible causes include allergies to medications. More than 150 drugs have been identified that can provoke the disease. These include some antibiotics, analgesics, radiopaque agents, serums, vaccines, as well as iodine preparations, B vitamins and other drugs. Allergies, autoimmune failure and the development of vasculitis do not always occur after taking them. The risk of such complications is determined by the individual reaction to the components of the drug. Therefore, it is important that all medications are selected by a doctor. You do not need to choose your own antibiotics or antihistamines.

Main types of vasculitis

Not all types of disease occur equally often. Some appear in rare cases, as a result of genetic disorders or individual characteristics of the body.

The most common types of disease that occur more often:

| Name | Characteristic |

| Hemorrhagic | It affects the blood vessels of the skin, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and joints. Capillaries become brittle due to damage by the body's immune system. Widely distributed among preschool and school ages. Occurs as a result of recent infectious diseases, vaccinations, hypothermia. |

| Allergic | Occurs due to the aggressive action of allergens. This reaction occurs to medications, chemical products, jewelry, and food. |

All types of vasculitis require a thorough examination by a doctor and diagnostic examination.

Symptoms of vasculitis

The manifestations of vasculitis are determined by the type of disease, location and size of the affected vessels. The most common symptoms that appear are:

- increased body temperature;

- weakness, malaise, fatigue;

- decreased appetite, nausea and vomiting;

- rapid weight loss;

- pain: headaches, muscles, joints;

- dizziness, loss of consciousness;

- pallor of the skin, the appearance of rashes on it (ulcers, purpura, petechiae);

- if there are cardiovascular diseases, they worsen;

- Possible decreased vision;

- change in skin sensitivity (from weak, almost absent to too strong);

- symptoms associated with organs whose functioning is impaired due to insufficient blood circulation (this may be decreased vision, symptoms of kidney failure, problems with the digestive system).

Figure 2. Skin rash due to vasculitis.

Source: CC0 Public Domain Symptoms of inflammation are the first to appear, regardless of the size of the affected vessels. Fever occurs, general malaise occurs, weight begins to decrease, joint pain appears, and sweating increases at night. If the walls of small and medium-sized vessels become inflamed, skin lesions appear almost immediately: rash (palpable purpura, urticaria, and others), the formation of ulcers, nodules, livedo reticularis.

Figure 3. Reticular erythema pattern typical of livedo reticularis in cutaneous vasculitis. Source: Springer Science/Business Media

Some of the symptoms of vasculitis can be life-threatening and require immediate treatment. These are alveolar hemorrhage, mesenteric ischemia, a sharp decrease in vision, glomerulonephritis (kidney damage).

The exact symptoms of vasculitis depend on its form:

- cutaneous - an itchy rash appears on the skin as a result of pinpoint hemorrhages. At first, its color is red, but then the rashes darken, disappear, and pigmented areas remain in their place. More often, such rashes form on the skin of the buttocks and legs;

- articular - manifested by swelling, impaired mobility of large joints, pain;

- abdominal - abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite;

- renal - change in the color of urine and a decrease in its volume. The urine turns red or pink. Clinical analysis reveals protein levels indicating glomerulonephritis. Without treatment, kidney failure develops.

Vasculitis in children

Vasculitis rarely appears in children. Almost always this is either hemorrhagic vasculitis or Kawasaki syndrome.

Kawasaki syndrome. Yonsei medical journal / Open-i (Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported)

Kawasaki syndrome is dangerous due to damage to the lymph nodes, heart vessels, and respiratory mucosa. The disease develops in an acute form with the sequential appearance of the following symptoms:

- severe fever with a rapid increase in temperature to 38-41 degrees;

- the appearance of a rash, erythematous spots on the skin;

- damage to the mucous membranes of the eyes, upper respiratory tract, nose;

- redness and then thickening of the skin on the palms and soles of the feet;

- inflammation, enlargement of lymph nodes in the neck;

- redness of the tongue;

- dryness and flaking of the skin on the phalanges of the fingers and toes, around the nails.

Kawasaki syndrome is dangerous due to damage to the cardiovascular system and the risk of aneurysm formation, but with timely diagnosis and treatment, the prognosis is favorable.

Hemorrhagic vasculitis in children can occur in several forms, including cutaneous, abdominal, skin-articular, and renal. Symptoms for each form vary:

- skin - the appearance of rash, swelling;

- abdominal - abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, loss of appetite, weight loss;

- renal - decrease in urine volume, change in its color, appearance of protein in the analysis;

- articular - the appearance of joint pain, limited mobility of large joints.

Vasculitis in adults

Vasculitis in adults develops as a result of disturbances in the functioning of the immune system. The main risk factors are severe infections, untimely or improper treatment of infectious diseases, taking medications without a doctor’s prescription, allergies to food or medications, and the use of certain medications.

Vasculitis occurs as a chronic, progressive disease, and in this case, its treatment requires complex and long-term therapy. The earlier the diagnosis is made and treatment started, the better the prognosis. In adults, inflammation of the walls of blood vessels can provoke life-threatening conditions, so it is important to consult a doctor promptly. Inflammation of the walls of blood vessels may be indicated by ongoing fever, symptoms associated with poor circulation, muscle, headaches, and joint pain.

Tests and diagnostics

Vasculitis can occur in several forms, and the symptoms for each of them will be different. Often they are “masked” as other diseases, and therefore a detailed diagnosis is needed. It starts with contacting a rheumatologist. He can refer you to a dermatologist, cardiologist, immunologist, nephrologist and other specialists.

Diagnosis begins with the following studies:

- clinical blood test. Allows you to identify inflammation, signs of allergies, immune reactions;

- general urine analysis. Evaluates the condition and function of the kidneys. With a high protein content, it indicates glomerulonephritis associated with kidney damage;

- coagulogram. Evaluates blood clotting. With vasculitis, it decreases, which increases the risk of hemorrhage.

Additionally, tests can be performed for antibodies to hepatitis B and C (often detected with vasculitis), a biopsy of the affected tissue, followed by histology (the study of cells). Some laboratory tests are used to determine the type of vasculitis, its etiology, and the degree of organ damage.

During diagnosis, an ECG is also prescribed to assess the condition of the heart, identify circulatory disorders, radiography, CT or MRI of affected organs or large blood vessels.

Diagnostics

It is necessary to try to diagnose vasculitis even in the presence of the very first signs. The disease is serious and dangerous and requires immediate treatment.

If you suspect an illness, you must perform a series of examinations and tests. Appointed:

- angiography;

- general blood and urine tests;

- ECHO-cardiography;

- blood biochemistry;

- Ultrasound of the heart, abdominal organs and kidneys;

- X-rays of light.

The problem is that it is very difficult to diagnose vasculitis in the early stages. But more striking signs of the disease and a reason to sound the alarm appear even when several organs are affected at once.

In severe and rapid progression of the disease, an additional biopsy is performed, followed by a detailed study of tissue samples.

Treatment

The approach to treating vasculitis is determined by the location of the affected vessels, the presence of concomitant diseases, the severity of the condition, and a number of other factors. Most often, complex therapy is used, which involves taking medications, physiotherapy, diet, and preventing exacerbations. In severe forms of the disease, if thrombosis of large arteries or stenosis of the great arteries develops, surgical treatment is indicated.

Drug treatment of vasculitis

Approaches to treating vasculitis vary in each case. The rheumatologist will prescribe medications to reduce the production of antibodies and reduce tissue sensitivity. In some cases, antibiotics are needed, in others, antiallergic drugs.

Photo: lucky7trader / freepik.com

The attending rheumatologist should draw up a drug treatment program. Additionally, he can attract other doctors of a more narrow specialization. You cannot try to cure the disease on your own. It is dangerous due to severe complications and requires systemic and complex therapy.

Medicines for vasculitis

Prescribed in order to achieve stable remission and reduce the risk of complications. With secondary vasculitis, therapy is aimed at treating the underlying disease that caused vascular inflammation.

The following drugs are used for treatment:

- glucocorticosteroids or steroid hormones. Prescribed in almost all cases, they have anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects. Doses of drugs are selected individually, creating a dosage schedule. Typically the dosage is high at first and then gradually reduced;

- cytostatics. They suppress the activity of the immune system, which allows for the correction of autoimmune mechanisms. Cytostatics are used in combination with glucocorticosteroids for severe forms of vasculitis. The drugs are prescribed as part of pulse therapy. It involves taking medications in short courses to avoid side effects;

- antitumor drugs, in particular Rituximab. These are monoclonal antibodies that are produced by immune cells, have immunosuppressive properties and are used in the treatment of systemic vasculitis if the use of cytostatics is undesirable. They are not prescribed for hepatitis B virus, neutropenia, low IgC levels in the blood and a positive tuberculin test.

Immunosuppressants (suppress the activity of the immune system), normal human immunoglobulin (used for infectious complications, severe kidney damage, development of hemorrhagic alveolitis), antibacterial, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, anticoagulants (prevent the formation of blood clots in blood vessels), antiallergic drugs can also be prescribed.

Physiotherapeutic methods for treating vasculitis

To treat vasculitis, plasmapheresis is used, in which blood is taken, purified and returned to the bloodstream. The technique is used as part of combination therapy if the disease is severe or acute and progresses rapidly. Plasmapheresis is prescribed in courses for severe kidney damage, as well as in cases where the use of cytostatics is contraindicated.

Treatment with folk remedies

Folk remedies are ineffective in treating vasculitis, and their use can be dangerous. If the disease progresses rapidly or becomes severe, you should immediately consult a doctor. Attempts to be treated with traditional methods will lead to a loss of time and can provoke complications.

Valeria Korol – general practitioner, rheumatologist, Member of the Expert Council of MedPortal

“Who is admitted to the hospital for vasculitis?

— All patients with newly diagnosed signs of systemic vasculitis. Special indications for hospitalization of patients with an established diagnosis of SV:

- Rapidly progressive deterioration of kidney function

- The appearance of protein in the urine - more than 3 g/day

- Recurring abdominal pain

- Damage to the organ of vision

- Signs of central nervous system damage"

Treatment of vasculitis

Treatment of vasculitis is prescribed depending on the type of organs affected and concomitant diseases. If the primary form of the disease appears against the background of an allergy, it usually disappears on its own and does not require additional measures.

If the source of the disease affects vital organs, such as the heart, brain, kidneys or lungs, then the patient is prescribed a course of intensive therapy.

To stabilize blood circulation, treatment can be carried out both at home and in a hospital setting. Pregnant women, children and patients with severe forms of the disease are required to be hospitalized.

Use:

- chemotherapy;

- corticosteroids;

- NSAIDs;

- anticoagulants;

- enterosorbents;

- antiplatelet agents;

- antihistamines;

- cytostatics.

Additionally, plasmapheresis, hemosorption and immunosorption are included.

Prevention

The causes of primary vasculitis are unknown, so special prevention is not carried out. Prevention of secondary vasculitis is carried out in several directions and involves restoration and maintenance of normal health:

- reducing the risk of contracting hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and other infections;

- timely and correct treatment of any diseases and especially infectious ones;

- taking medications only as prescribed by a doctor;

- maintaining a healthy lifestyle: maintaining a normal weight, giving up bad habits, proper nutrition and sufficient physical activity;

- allergy control. If they exist, it is important to exclude allergic reactions to food and medicines.

Diet for vasculitis

The diet for vasculitis is designed to eliminate food allergies, normalize weight, and provide the daily requirement for calories, vitamins, minerals, etc. When forming a diet, they take into account the causes that provoked vasculitis and which organs were affected due to inflammation of the walls of blood vessels and poor circulation. For example, if the stomach or intestines are damaged, a special nutrition plan is needed.

General recommendations involve organizing a healthy diet: excluding foods that cause an allergic reaction, eating enough fresh vegetables and fruits, dairy products, cereals, excluding fatty, spicy, fried foods. In each individual case, you can contact a nutritionist for help in creating a diet.

Where does vasculitis come from?

Doctors don't know for sure. It is known that sometimes Vasculitis - Symptoms and causes / Mayo Clinic vasculitis is associated with genetics and is inherited. But more often it happens that a person’s immune system goes crazy and mistakenly begins to attack the cells of the blood vessels of its own body.

Why this happens is not entirely clear. However, doctors have discovered several Vasculitis - Symptoms and causes / Mayo Clinic factors that precede such an immune failure:

- Acute infectious diseases. During them, viruses, bacteria, and fungi sometimes penetrate the walls of blood vessels, which may cause increased immune activity.

- Chronic infections. For example, hepatitis B and C.

- Causes of Vasculitis / Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center allergic-type reactions to new medications or toxins that have entered the body.

- Diseases of the immune system. This could be, say, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma or lupus.

- Blood cancer.

This is by no means a complete list. But it is not yet possible to make it exhaustive. Researchers honestly admit that very often they simply do not understand why the vessels become inflamed in a particular case.

Consequences and complications

Without treatment, vasculitis becomes a life-threatening disease. It can cause pulmonary, intestinal and intracranial bleeding, thrombosis, renal or liver failure, myocardial infarction, and aneurysms. Possible complications include:

- intestinal obstruction;

- peritonitis;

- pancreatitis;

- heart attacks, thrombosis, ischemia of tissues and organs;

- perforation of intestinal and stomach ulcers;

- neuritis, cerebral disorders.

Even with timely treatment of vasculitis and persistent remission of the disease, consequences are possible, including chronic diseases of the kidneys, liver, digestive organs, breathing, hearing loss, vision loss and others. In order to most effectively restore normal health and quality of life, long-term systemic therapy is carried out.

Forecast

Depends on the form, localization of vasculitis, severity of the disease. In some cases, primary vasculitis goes away without treatment and leaves no consequences at all. In others, the disease develops rapidly and is life-threatening. It is important to consult a general practitioner or rheumatologist in time, immediately after the first symptoms appear. The main danger with most forms of vasculitis is possible complications:

- severe cardiovascular diseases, heart attacks with polyarteritis nodosa;

- development of infections and pulmonary hemorrhages with microscopic polyarteritis;

- infections, renal, respiratory failure, cardiovascular accidents with Wegener's granulomatosis;

- partial or complete loss of vision with giant cell arteritis (but overall the prognosis is favorable);

- strokes, heart attacks with Takayasu arteritis.

To improve the prognosis, it is important to strictly follow the recommendations of the attending physician, try to prolong the remission of the disease, and eliminate factors that provoke relapses.

Valeria Korol – general practitioner, rheumatologist, Member of the expert council of MedPortal “How to avoid recurrent vasculitis?

— Avoid factors that can provoke an exacerbation of the disease:

- Infections

- Stress

- Exposure to direct sunlight

- Unmotivated medication use

- To give up smoking

- Normalization of body weight

- Valeria Korol

- general practitioner, rheumatologist"